Pliny the Elder on Gilding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium*

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium* MELINDA SZEKELY Pliny the Elder writes the following about the king of Taprobane1 in the sixth book of his Natural History: "eligi regem a populo senecta clementiaque, liberos non ha- bentem, et, si postea gignat, abdicari, ne fiat hereditarium regnum."2 This account es- caped the attention of the majority of scholars who studied Pliny in spite of the fact that this sentence raises three interesting and debated questions: the election of the king, deposal of the king and the heredity of the monarchy. The issue con- cerning the account of Taprobane is that Pliny here - unlike other reports on the East - does not only use the works of former Greek and Roman authors, but he also makes a note of the account of the envoys from Ceylon arriving in Rome in the first century A. D. in his work.3 We cannot exclude the possibility that Pliny himself met the envoys though this assumption is not verifiable.4 First let us consider whether the form of rule described by Pliny really existed in Taprobane. We have several sources dealing with India indicating that the idea of that old and gentle king depicted in Pliny's sentence seems to be just the oppo- * The study was supported by OTKA grant No. T13034550. 1 Ancient name of Sri Lanka (until 1972, Ceylon). 2 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 89. Pliny, Natural History, Cambridge-London 1989, [19421], with an English translation by H. Rackham. 3 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 85-91. Concerning the Singhalese envoys cf. -

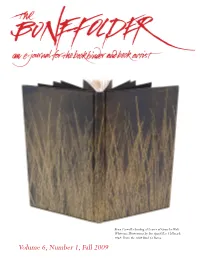

The Bonefolder: an E-Journal for the Bookbinder and Book Artist Surface Gilding by James Reid-Cunningham

Bexx Caswell’s binding of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman; Illustrations by Jim Spanfeller. Hallmark, 1969. From the 2009 Bind-O-Rama. Volume 6, Number 1, Fall 2009 The Bonefolder: an e-journal for the bookbinder and book artist Surface Gilding By James Reid-Cunningham 28 Figure 1. The House South of North. Calfskin, gold leaf, Figure 2. Transfer leaf. palladium leaf, kidskin, fish skin, goatskin, box calf, abalone. Gilding on large flat surfaces is best done with transfer leaf Bound 2006. (also called patent leaf), which is gold leaf mounted on a piece Traditional binding decoration utilizes gold leaf to create of thin tissue that allows easily handling without wrinkling or discrete highlights, as in gold finishing. What I refer to as breaking the gold leaf. Transfer leaf can be cut with a scissors. “surface gilding” covers a binding with gold leaf over large Use a scissors reserved only for this task because any scratch areas, even over entire boards. This kind of decoration is rare or little bit of adhesive on the blade will pull the leaf and in bookbinding history, but can be seen in Art Deco bindings break it. When using loose gold leaf, it is necessary to adhere done in France during the 1920s and 1930s. Surface gilding the leaf to the substrate using oil or Vaseline. has become increasingly common among design binders in It sometimes seems that any adhesive ever invented recent years. Whether bound in leather, paper or vellum, has been used at one point or another to adhere gold to a surface gilding gives a spectacularly luxurious effect to a book, so there are many choices of what to use. -

Or on the ETHICS of GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc

SHOULD CONSERVATORS REGILD THE LILY? or ON THE ETHICS OF GILDING CONSERVATION by Elisabeth Cornu, Assoc. Conservator, Objects Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Gilt objects, and the process of gilding, have a tremendous appeal in the art community--perhaps not least because gold is a very impressive and shiny currency, and perhaps also because the technique of gilding has largely remained unchanged since Egyptian times. Gilding restorers therefore have enjoyed special respect in the art community because they manage to bring back the shine to old objects and because they continue a very old and valuable craft. As a result there has been a strong temptation among gilding restorers/conservators to preserve the process of gilding rather than the gilt objects them- selves. This is done by regilding, partially or fully, deteriorated gilt surfaces rather than attempting to preserve as much of the original surface as possible. Such practice may be appropriate in some cases, but it always presupposes a great amount of historic knowledge of the gilding technique used with each object, including such details as the thickness of gesso layers, the strength of the gesso, the type of bole, the tint and karatage of gold leaf, and the type of distressing or glaze used. To illustrate this point, I am asking you to exercise some of the imagination for which museum conservators are so famous for, and to visualize some historic objects which I will list and discuss. This will save me much time in showing slides or photographs. Gilt wooden objects in museums can be broken down into several subcategories: 1) Polychromed and gilt sculptures, altars Examples: baroque church altars, often with polychromed sculptures, some of which are entirely gilt. -

Supplied Through the Parthians) from the 1St Century BC, Even Though the Romans Thought Silk Was Obtained from Trees

Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire Trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees: The Seres (Chinese), are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves... So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public. -(Pliny the Elder (23- 79, The Natural History) The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. -(Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE- 65 CE, Declamations Vol. I) The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (perhaps the Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE: Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. -

Ancient Authors 297

T Ancient authors 297 is unknown. His Attic Nights is a speeches for the law courts, collection of essays on a variety political speeches, philosophical ANCIENT AUTHORS of topics, based on his reading of essays, and personal letters to Apicius: (fourth century AD) is the Greek and Roman writers and the friends and family. name traditionally given to the lectures and conversations he had Columella: Lucius Iunius author of a collection of recipes, heard. The title Attic Nights refers Moderatus Columella (wrote c.AD de Re Coquinaria (On the Art of to Attica, the district in Greece 60–65) was born at Gades (modern Cooking). Marcus Gavius Apicius around Athens, where Gellius was Cadiz) in Spain and served in the was a gourmet who lived in the living when he wrote the book. Roman army in Syria. He wrote a early first centuryAD and wrote Cassius Dio (also Dio Cassius): treatise on farming, de Re Rustica about sauces. Seneca says that he Cassius Dio Cocceianus (c.AD (On Farming). claimed to have created a scientia 150–235) was born in Bithynia. He popīnae (snack bar cuisine). Diodorus Siculus: Diodorus had a political career as a consul (wrote c.60–30 BC) was a Greek Appian: Appianos (late first in Rome and governor of the from Sicily who wrote a history of century AD–AD 160s) was born in provinces of Africa and Dalmatia. the world centered on Rome, from Alexandria, in Egypt, and practiced His history of Rome, written in legendary beginnings to 54 BC. as a lawyer in Rome. -

Pliny's "Vesuvius" Narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20)

Edinburgh Research Explorer Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20) Citation for published version: Berry, D 2008, Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20). in F Cairns (ed.), Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar . vol. 13, Francis Cairns Publications Ltd, pp. 297-313. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Published In: Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar Publisher Rights Statement: ©Berry, D. (2008). Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20). In F. Cairns (Ed.), Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar . (pp. 297-313). Francis Cairns Publications Ltd. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 LETTERS FROM AN ADVOCATE: Pliny’s ‘Vesuvius’ Narratives (Epp. 6.16, 6.20)* D.H. BERRY University of Edinburgh To us in the modern era, the most memorable letters of Pliny the Younger are Epp. 6.16 and 6.20, addressed to Cornelius Tacitus. -

Under the Influence of Art: the Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius

Under the Influence of Art: The Effect of the Statues of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia on Valerius Maximus’ Facta et Dicta Memorabilia In his work, Facta et Dicta Memorabilia, Valerius Maximus stated in the praefatio of his chapter “De Fortitudine” that he will discuss the great deeds of Romulus, but cannot do so without bringing up one example first; someone whose similarly great deeds helped save Rome (3.2.1-2). This great man is Horatius Cocles. Valerius Maximus noted that he must next talk about another hero, Cloelia, after Horatius Cocles because they fight the same enemy, at the same time, at the same place, and both perform facta memorabilia to save Rome (3.2.2-3). Valerius Maximus mentioned Horatius Cocles and Cloelia together, as if they are a joined pair that cannot be separated. Yet there is another legendary figure, Mucius Scaevola, who also fights the same enemy, at the same time, and also performs facta memorabilia to save Rome. It is strange both that Valerius Maximus seemed compelled to unite Cloelia with the mention of Horatius Cocles, and also that he did not include Mucius Scaevola. Instead, Scaevola’s story is at the beginning of the next chapter (3.3.1). Traditionally these three heroes, Horatius Cocles, Cloelia, and Mucius Scaevola, were mentioned together by historians such as Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, whose works predate Valerius Maximus’ (Ab Urbe Condita 2.10-13, Roman Antiquities 5.23-35). Valerius Maximus was able to split up the triad, despite the tradition, without receiving flack because it had already been done by Virgil in the Aeneid, where he described the dual images of Cocles and Cloelia on Aeneas’ shield, but Scaevola is absent (8.646-651). -

Pliny's Poisoned Provinces

A DANGEROUS ART: GREEK PHYSICIANS AND MEDICAL RISK IN IMPERIAL ROME DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Molly Ayn Jones Lewis, B.A., M.A. ********* The Ohio State University May, 2009 Dissertation Committee: Duane W. Roller, Advisor Approved by Julia Nelson Hawkins __________________________________ Frank Coulson Advisor Greek and Latin Graduate Program Fritz Graf Copyright by Molly Ayn Jones Lewis 2009 ABSTRACT Recent scholarship of identity issues in Imperial Rome has focused on the complicated intersections of “Greek” and “Roman” identity, a perfect microcosm in which to examine the issue in the high-stakes world of medical practice where physicians from competing Greek-speaking traditions interacted with wealthy Roman patients. I argue that not only did Roman patients and politicians have a variety of methods at their disposal for neutralizing the perceived threat of foreign physicians, but that the foreign physicians also were given ways to mitigate the substantial dangers involved in treating the Roman elite. I approach the issue from three standpoints: the political rhetoric surrounding foreign medicines, the legislation in place to protect doctors and patients, and the ethical issues debated by physicians and laypeople alike. I show that Roman lawmakers, policy makers, and physicians had a variety of ways by which the physical, political, and financial dangers of foreign doctors and Roman patients posed to one another could be mitigated. The dissertation argues that despite barriers of xenophobia and ethnic identity, physicians practicing in Greek traditions were fairly well integrated into the cultural milieu of imperial Rome, and were accepted (if not always trusted) members of society. -

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay by Lauren Sepp

Gilding with Kolner Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay By Lauren Sepp ’ve been asked many times by custom framing re- achieve different shades. The white Burnishing Clay tailers if there is an easier way to water gild and can be tinted with Mixol tinting agents up to 5 percent I burnish a surface, as it’s generally agreed upon that by weight to achieve any color you desire. traditional water gilding is a labor-intensive method. Both the Burnishing Clay and Insta-Clay can be Kolner products address that demand by streamlining applied to many different surfaces. Certain nonpo- the water gilding process, which would otherwise in- rous substrates require no sealing before application clude many more steps. of the clay: Plexiglas and other plastics, sealed woods, Kolner Products, based in Germany, formulated a nonporous paints, and lacquered metals. Unsealed water-based, single-layer, burnishable gilders’ clay for metals may require a primer. Smooth plastics and water gilding in 1985 called Kolner Burnishing Clay. metals may require a light sanding to promote good This product combines and replaces the glue size, ges- adhesion. Porous surfaces such as matboard, paper, so, and bole layers with a single product. The clay is parchment, raw wood, textiles, unglazed ceramics, premixed with an acrylic binder and only needs to be stone, plaster, traditional gesso and compo orna- thinned slightly and stirred. There is no heating, dis- ments require a sealer before applying the clays. In solving of glues, or straining. There is also a sprayable many applications, shellac is a good all-around sealer. -

Gilding Through the Ages

Gilding Through the Ages AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE PROCESS IN THE OLD WORLD Andrew Oddy Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. In 1845, Sir Edward Thomason wrote in his not public concern but technological advance which memoirs (1) a description of a visit he had made in brought an end to the use of amalgam for gilding. to certain artisans in Paris and he commented: 1814 Gilding with Gold Foil `I was surprised, however, at their secret of superior Although fire-gilding had been in widespread use in gilding of the time-pieces. I was admitted into one gilding establishment, and I found the medium was Europe and Asia for at least 1 500 years when it was similar to ours, mercury; nevertheless the French did displaced by electroplating, the origins of gilding — gild the large ornaments and figures of the chimney- that is, the application of a layer of gold to the surface piece clocks with one-half the gold we could at of a less rare metal — go back at least 5 000 years, to Birmingham, and produced a more even and finer the beginning of the third millennium B.C. The colour'. British Museum has some silver nails from the site of Much to his disgust, Thomason could not persuade Tell Brak in Northern Syria (5) which have had their the French workmen to tell him the secret of their heads gilded by wrapping gold foil over the silver. superior technique, but it seems most likely that it This is, in fact, the earliest form of gilding and it lay either in the preparation of the metal surface depends not on a physical or chemical bond between for gilding or perhaps in the final cleaning and the gold foil and the substrate, but merely on the burnishing of the gilded surface. -

Rev6. Doody Ch

Authority and Authorship in the Medicina Plinii1 Aude Doody Authority is central to the practice of medicine. In antiquity, in the absence of strong institutional frameworks guaranteeing a doctor’s credentials, creating the right impression of knowledge, skill and moral character was a serious concern for the individual practitioner. The instructions on everything from bedside manner to personal morality contained in ancient medical texts from the Hippocratic Corpus to Galen bear witness to the pressing nature of the doctor’s efforts to establish an authoritative persona which would encourage trust between himself and his patients. But if persuading the patient of his authority was important to the individual doctor, claims to authority were also central to the project of producing a medical text. A medical text needed to persuade the reader that its information was accurate and effective, and, as in the case of the doctor, this persuasion rested not just on proven results, but on persuasive strategies employed by the text’s author. As the articles in this volume demonstrate, these strategies vary from text to text and from author to author. Galen, for instance, claims authority through his engagement with philosophical concerns, the emphasis on the physician’s practical experience, his polemical and doxographical approach to earlier authorities, but he also relies on the creation of a strong authorial persona, his demonstration of careful philological practice, and the interplay between the many texts he has written.2 My aim here is to explore the specific problems that confront the author of a pseudonymous book of extracts, the Medicina Plinii, and the peculiar set of difficulties that its genre and its pseudonymity pose for how authority can be established. -

A Reconsideration of Giovanni Vendramin's Architectural

“The Triumph of the Text:” A Reconsideration of Giovanni Vendramin’s Architectural Frontispieces Lisandra Estevez Giovanni Vendramin (active 1466-1508) was one of the most emphasizes the treatment of the text as a monumental cul- distinguished Paduan miniaturists of the Quattrocento.1 Many tural artifact, evoking an idealized realm of classical learn- of the manuscripts that he illustrated were commissioned by ing, where the primacy of the written word is heralded. The Bishop Jacopo Zeno of Padua (r. 1460-1481), an important colossal architectural forms employed to construct an illus- humanist and patron of the arts.2 This paper will consider the trated frame for a particular passage are removed from their role of classicism and antiquarianism in the architectural fron- functional purpose and are converted to an ornamental scheme tispieces that Vendramin painted as a prominent introduction that ultimately serves as a support for a given text, highlight- to many of the books he decorated and suggest a new source ing the text as the central figural component. The addition of for them. These frontispieces are a major marker of the fasci- a monumental form in service of the text, thus, transformed nation with the revival of the Greco-Roman tradition during the character of the architectural frontispiece.3 the Renaissance, but have been less studied than related phe- Now let us compare the frontispieces to canon tables. The nomena in the monumental arts, for example, Mantegna’s canon table was developed in the fourth century by bishop paintings. The development of the new type of frontispiece Eusebius of Caesarae.4 It served as a concordance for the Gos- coincided with the publication of newly translated, edited, or pels in Byzantine manuscripts and functioned primarily within discovered classical texts such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural a religious context.