4 South Harris Settlement-Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Monitoring Project 2004-2006

COASTAL MONITORING PROJECT 2004-2006 By Tim Ryle, Anne Murray, Kieran Connolly & Melinda Swann A Report to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, Dublin. 2009 Coastal Monitoring Project Coastal Monitoring Project EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Irish coastline, including the islands, extends to 6,000 kilometres, of which approximately 750 kilometres is sandy. The sand dune resource is under threat from a number of impacts – primarily natural erosion, changes in agricultural practices and development of land for housing, tourism and recreational purposes. This project, carried out on behalf of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), is designed to meet Ireland’s obligation under Article 17 of the EU Habitats Directive, in relation to reporting on the conservation status of Annex I sand dune habitats in Ireland. The following habitats were assessed: 1210 – Annual vegetation of driftlines 1220 – Perennial vegetation of stony banks 2110 – Embryonic shifting dunes 2120 – Shifting dunes along the shoreline with Ammophila arenaria 2130 – Fixed coastal dunes with herbaceous vegetation (grey dunes) 2140 – Decalcified fixed dunes with Empetrum nigrum 2150 – Atlantic decalcified fixed dunes (Calluno-Ulicetea) 2170 – Dunes with Salix repens ssp. argentea (Salicion arenariea) 2190 – Humid dune slacks 21A0 – Machairs The project is notable in that it represents the first comprehensive assessments of sand dune systems and their habitats in Ireland. Over the course of the three field seasons (2004-2006), all known sites for sand dunes in Ireland were assessed (only 4 sites were not visited owing to access problems). The original inventory of sand dune systems by Curtis (1991a) listed 168 sites for the Republic of Ireland. -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

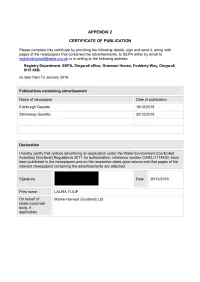

Appendix 2 Certificate of Publication

APPENDIX 2 CERTIFICATE OF PUBLICATION Please complete this certificate by providing the following details, sign and send it, along with pages of the newspapers that contained the advertisements, to SEPA either by email to registrydingwall@sepa. org.uk or in writing to the following address: Registry Department, SEPA, Dingwall office, Graesser House, Fodderty Way, Dingwall, IV15 9XB no later than 12 January 2019. Publications containing advertisement Name of newspaper Date of publication Edinburgh Gazette 18/12/2018 Stornoway Gazette 20/12/2018 Declaration I hereby certify that notices advertising an application under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 for authorisation, reference number CAR/L/1174430, have been published in the newspapers and on the respective dates given above and that pages of the relevant newspapers containing the advertisements are attached. Signature Date 20/12/2018 Print name LAURA TULIP On behalf of Marine Harvest (Scotland) Ltd state corporate body, if applicable) Thursday, 0cmmbe, 20, 2( 118 Axw Qq29 . PUBLIC NOTICES I GENERAL VACANCIES WATER ENVIRONMENT AND WATER SERVICES CROFTING SCOTLAND) ACT 2003 COMMISSION WATER ENVIRONMENT ( CONTROLLED ACTIVITIES) ( SCOTLAND) COIMISEAN NA REGULATIONS 2011 CROITEARACHD GENERAL VACANCIES _ I R DECROFTING APPLICATION FOR AUTHORISATION APPLICATION IE' G GREY HORSE CHANNEL OUTER MARINE CAGE FISH FARM Broadbay Medical Practice An application has been made to the Scottish Environment Protection Agency Miss M M MacDonald SEPA) by Marine Harvest ( Scotland) Ltd for authorisation to carry on a 6 Doune Cadoway, Uig General Practice Advanced We are currently seeking an experienced controlled activity at, near or in connection with Grey Horse Channel Outer 0. -

Bunduff Lough and Machair Trawalua Mullaghmore

NPWS Bunduff Lough and Machair/Trawalua/Mullaghmore SAC (site code: 625) Conservation objectives supporting document - Marine Habitats Version 1 February 2015 Introduction Bunduff Lough and Machair/Trawalua/Mullaghmore SAC is designated for the marine Annex I qualifying interests of Mudflats and sandflats not covered by seawater at low tide, Large shallow inlets and bays and Reefs (Figures 1, 2 and 3). The Annex I habitat Large shallow inlets and bays is a large physiographic feature that may wholly or partly incorporate other Annex I habitats including mudflats and sandflats and reefs within its area. A BioMar survey of this site was carried out in 1994 (Picton and Costello, 1997) and subtidal and intertidal surveys were undertaken in 2011 and 2012 (MERC, 2012a and b); InfoMar (Ireland’s national marine mapping programme) data from the site was also reviewed. These data were used to determine the physical and biological nature of this SAC. Aspects of the biology and ecology of the Annex I habitat are provided in Section 1. The corresponding site-specific conservation objectives will facilitate Ireland delivering on its surveillance and reporting obligations under the EU Habitats Directive (92/43/EC). Ireland also has an obligation to ensure that consent decisions concerning operations/activities planned for Natura 2000 sites are informed by an appropriate assessment where the likelihood of such operations or activities having a significant effect on the site cannot be excluded. Further ancillary information concerning the practical application of the site-specific objectives and targets in the completion of such assessments is provided in Section 2. 2 Section 1 Principal Benthic Communities Within Bunduff Lough and Machair/Trawalua/Mullaghmore SAC, three community types are recorded. -

North Country Cheviot

SALE CATALOGUE Ram Sale 7th October 2019. Show 4pm Sale 5pm Note to sellers: Seller of livestock must be present prior to livestock entering the sale ring. Should seller or representative not be present, livestock will be passed over until end of sale. Sale kindly sponsored by Lewis and Harris Sheep Producers Association Supreme Champion £50 Reserve Champion £25 Name Address No Class Pen QMS North Country Cheviot Iain Roddy Morrison 11a Kershader 1 Lamb 2 James Macarthur 50 Back 2 Lambs 2 Do Do 1 3 Shear 2 Colin Macleod 13 Swordale 1 2 Shear 2 Donald Montgomery 11 Garyvard 1 3 Shear 2 Sandra MacBain 25 Garrabost 1 3 Shear Achentoul bred 2 017883 Alex Macdonald 32 Garrabost 1 Hill Shearling 2 017372 Do Do 1 Hill Type 2 Shear 2 Gordon Mackay 9 School Park Knock 1 Cheviot Shearling 2 D D Maciver 1 Portnaguran 2 Hill Cheviot 2 Shear 3 Do Do 1 Hill Cheviot Shearling 3 AJ & C Maclean 13 Cross Skigersta Rd 1 2 Shear (Park) 3 008050 Achondroplasia clear Do Do 1 2 Shear (Hill) 3 008050 Achondroplasia clear Murdie Maciver 8 Coll 4 Hill Cheviot Shearlings 3 Donnie Nicolson 29 Flesherin 1 Hill Shearling 3 Alex J Ross 6 Sand Street 2 Hill Cheviot 2 Shear 4 014225 Do Do 2 Hill Cheviot 4 Shear 4 Kenny Paterson New Park Callanish 1 Shearling 4 John N Maclean 38 Lower Barvas 1 2 Year old 4 Annie Macleod 15 Skigersta 1 2 Shear 4 Do Do 1 3 Shear 4 Murdo Murray 47a Back 1 Lamb 4 Do Do 1 4 Shear 4 Calum Macleod Waters Edge 2 Shearlings 5 Do Do 3 2 Shear 5 Murdo Morrison 46a North Tolsta 1 4 Shear 5 Murdo Macdonald Carloway House 1 Hill type 3 Shear 5 Do Do -

Rosslare Wexford County (Ireland)

EUROSION Case Study ROSSLARE WEXFORD COUNTY (IRELAND) Contact: Paul SISTERMANS Odelinde NIEUWENHUIS DHV group Laan 1914 nr.35, 3818 EX Amersfoort 21 PO Box 219 3800 AE Amersfoort The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)33 468 37 00 Fax: +31 (0)33 468 37 48 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 1 EUROSION Case Study 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA 1.1 Physical process level 1.1.1 Classification Unlike the UK, Ireland has been rising out of the sea since the last ice age. Scientists think that the island has stopped rising and the sea level rise will become a bigger threat in the future. The biggest threat is climate change. The increase in sea level and high tides will produce a new threat to the coastline and with it fears for buildings and infrastructure along the shore. The case area is located at St. Georges Channel. The case area consists of soft glacial cliffs at the southern end and sandy beaches at the northern end. According to the typology in the scoping study the case area consists of: 1b. Tide-dominated sediment. Plains. Barrier dune coasts Fig. 1: Location of case area. 2a. Soft cliffs High and low glacial sea cliffs. 1.1.2 Geology Coast of Ireland Topography, together with linked geological controls, result in extensive rock dominated- and cliffed coastlines for the southwest, west and north of Ireland. In contrast, the east and southeastern coasts are comprised of unconsolidated Quaternary aged sediments and less rock exposures. Glacial and fluvial action however, has also created major sedimentary areas on western coasts. -

Characterising Archaeology in Machair

Characterising archaeology in machair John Barber AOC Archaeology Group Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 48, 2011 www.sair.org.uk CONTENTS List of Illustrations. 40 1 Abstract . .41 2 Introduction. 42 3 Distinguishing ‘Archaeology’ from ‘Not Archaeology’. 44 4 Characterising Archaeological Deposits and Formations . .45 4.1 Dynamism and sensitivity: processes of whole-site formation. 4 4.1.1 Deflation . 47 4.1.2 Conflation. 47 4.1.3 Diachronic deposits. 47 5 Deposit Formation . .48 .1 Dump deposits. 48 .2 Midden . 48 .3 Anthropic deposits . 48 .4 Midden sites . 49 . Cultivated deposits . 49 6 Preservation in Machair Soils . 50 6.1 Chronology building on machair sites . 0 6.2 Loss of sediments . 0 6.3 Practical problems in the use of radiocarbon dating on machair sites . 0 7 Curatorial Response. 52 8 References . .53 39 LIST OF ILLUStrations 1 Models of machair evolution (after Ritchie 1979). 43 2 a, b, c Plates showing development of settlement-related deposits. 4 3 The domed structure of the site at Baleshare, with cross-section.. 46 40 1 ABSTRACT This paper deals with methodological issues building can lead to misleading results. Rather, the involved in excavating in the machair, shell-sand focus must be on understanding and dating the systems of the Outer Hebrides and the West Coast sedimentary sequence and then intercalating the of Scotland. The machair system is character- sequence of human activities into that depositional ised by high rates of change, driven by Aeolian chronology. The almost universal availability of forces, interspersed with which human settle- radiometrically datable organic materials is vitiated ment intermittently occupied sites and altered by the difficulties they pose for dating, and careful the depositional regime, only in turn to have its selection from taphonomically sound contexts is deposits altered by subsequent human and natural a sine qua non. -

The Invertebrate Fauna of Dune and Machair Sites In

INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY (NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL) REPORT TO THE NATURE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL ON THE INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF DUNE AND MACHAIR SITES IN SCOTLAND Vol I Introduction, Methods and Analysis of Data (63 maps, 21 figures, 15 tables, 10 appendices) NCC/NE RC Contract No. F3/03/62 ITE Project No. 469 Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton Huntingdon Cambs September 1979 This report is an official document prepared under contract between the Nature Conservancy Council and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without permission from both the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology and the Nature Conservancy Council. (i) Contents CAPTIONS FOR MAPS, TABLES, FIGURES AND ArPENDICES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OBJECTIVES 2 3 METHODOLOGY 2 3.1 Invertebrate groups studied 3 3.2 Description of traps, siting and operating efficiency 4 3.3 Trapping period and number of collections 6 4 THE STATE OF KNOWL:DGE OF THE SCOTTISH SAND DUNE FAUNA AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SURVEY 7 5 SYNOPSIS OF WEATHER CONDITIONS DURING THE SAMPLING PERIODS 9 5.1 Outer Hebrides (1976) 9 5.2 North Coast (1976) 9 5.3 Moray Firth (1977) 10 5.4 East Coast (1976) 10 6. THE FAUNA AND ITS RANGE OF VARIATION 11 6.1 Introduction and methods of analysis 11 6.2 Ordinations of species/abundance data 11 G. Lepidoptera 12 6.4 Coleoptera:Carabidae 13 6.5 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae 14 6.6 Araneae 15 7 THE INDICATOR SPECIES ANALYSIS 17 7.1 Introduction 17 7.2 Lepidoptera 18 7.3 Coleoptera:Carabidae 19 7.4 Coleoptera:Hydrophilidae to Scolytidae -

The Implications of Climate Change for Coastal Habitats in the Uists, Outer Hebrides

Ocean & Coastal Management 94 (2014) 38e43 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ocean & Coastal Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocecoaman The implications of climate change for coastal habitats in the Uists, Outer Hebrides Stewart Angus* Scottish Natural Heritage, Great Glen House, Leachkin Road, Inverness, Scotland IV3 8NW, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: The low-lying, relatively flat landscape of the western seaboard of the Uists has a particular vulnerability Available online 27 March 2014 to climate change, especially to rising sea levels. Winter water tables are high, and a high proportion of the area is permanent open water and marsh. Any changes in aquatic relationships could pose serious problems for the Uist environment, where the closely inter-connected habitats are internationally rec- ognised for their conservation value. The uncertainty of most aspects of climate change is imposed upon an existing level of high climatic variability in the Western Isles, greatly complicating local habitat and land use scenarios, but rising sea level, possibly the most threatening aspect of climate change, is a certainty. Rising sea level alone has the potential to raise water levels within the islands by progressively reducing the effectiveness of an ageing drainage network, not only raising water levels, but possibly also facilitating saline infiltration of the water table. This raises problems for habitats, species, and for land users, in islands where habitat processes and human interaction with the environment have always been particularly closely linked. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction generally alkaline because of its high shell content, while the landward blanket bogs are often highly acid. -

SCOTLAND Lewis & Harris

SCOTLAND Lewis & Harris: Seabirds & Standing Stones 26 April – 2 May 2014 TOUR REPORT Leader: Steve Duffield Saturday 26 April Everything ran nice and smoothly and the flight and ferry arrived on time allowing us to quickly head across the Pentland Road to the Doune Braes Hotel where we unpacked and headed out for the rest of the afternoon. Weather wise are first afternoon was quite pleasant as the easterly wind eased in the evening and the sun made several appearances making it a pleasant 3 ½ hours in the field. After settling into the hotel in Carloway we headed along the north-west coast to Loch Ordais, Bragar. Here we took a walk between the storm beach and the freshwater loch picking up a great northern diver and a small flock of red-breasted mergansers on the sea. The loch held a few shelduck whilst small groups of Icelandic bound white wagtails and rock pipits searched the boulder beach for flies. From here we made our way to the more sheltered valley at Dalbeg. A small freshwater loch nestles in the valley bottom close to the sea and was home on our visit to a lone whooper swan. Fulmars and gannets could be seen wheeling beyond the cliffs whilst two red-throated divers bobbed on the sea. Wheatears appeared to be everywhere and were a real feature of the week. We made our way to Carloway and turned off towards Gearrannan where we spotted a black-tailed godwit in a marshy area near the turning. Continuing towards the black house village we had just parked when Andrew spotted a Harris hawk perched on a nearby fence. -

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE Iseag 185 Mìle • 10 Island a Iles • S • 1 S • 2 M 0 Ei Rrie 85 Lea 2 Fe 1 Nan N • • Area 6 Causeways • 6 Cabhsi WELCOME

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE 185 Miles • 185 Mìl e • 1 0 I slan ds • 10 E ile an an WWW.HEBRIDEANWAY.CO.UK• 6 C au sew ays • 6 C abhsiarean • 2 Ferries • 2 Aiseag WELCOME A journey to the Outer Hebrides archipelago, will take you to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world. Stunning shell sand beaches fringed with machair, vast expanses of moorland, rugged hills, dramatic cliffs and surrounding seas all contain a rich biodiversity of flora, fauna and marine life. Together with a thriving Gaelic culture, this provides an inspiring island environment to live, study and work in, and a culturally rich place to explore as a visitor. The islands are privileged to be home to several award-winning contemporary Art Centres and Festivals, plus a creative trail of many smaller artist/maker run spaces. This publication aims to guide you to the galleries, shops and websites, where Art and Craft made in the Outer Hebrides can be enjoyed. En-route there are numerous sculptures, landmarks, historical and archaeological sites to visit. The guide documents some (but by no means all) of these contemplative places, which interact with the surrounding landscape, interpreting elements of island history and relationships with the natural environment. The Comhairle’s Heritage and Library Services are comprehensively detailed. Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle in Stornoway, by special loan from the British Museum, is home to several of the Lewis Chessmen, one of the most significant archaeological finds in the UK. Throughout the islands a network of local historical societies, run by dedicated volunteers, hold a treasure trove of information, including photographs, oral histories, genealogies, croft histories and artefacts specific to their locality. -

D NORTH HARRIS UIG, MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS

GEOLOGY of the OUTER HEBRIDES -d NORTH HARRIS and UIG, MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS. by Robert M. Craig, iii.A., B.Sc. GEOLOGY of the OUTER HEBRIDES - NORTH HARRIS and UIG, 'MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS. CONTENTS. I. Introduction. TI. Previous Literature. III. Summary of the Rock Formations. IV. Descriptions of the Rock Formations - 1. The Archaean Complex. (a). Biotite- Gneiss. b). Hornblende -biotite- gneiss. d).). Basic rocks associated with (a) and (b). Acid hornblende -gneiss intrusive into (a) and (b). e . Basic Rocks intrusive into (a) and (b). f Ultra -basic Rocks. g ? Paragneisses. h The Granite- Gneiss. i Pegmatites. ?. Zones of Crushing and Crushed Rocks. S. Later Dykes. V. Physical Features. VI. Glaciation and Glacial Deposits. VII. Recent Changes. VIII. Explanation of Illustrations. I. INTRODUCTION. The area of the Outer Hebrides described in this paper includes North Harris and the Uig, Morsgail and Aline districts in Lewis. In addition, a narrow strip of country is included, north of Loch Erisort and extending eastwards from Balallan as far as the river Laxay on the estate of Soval. North Harris and its adjacent islands such as Scarp and Fladday on the west, and Soay in West Loch Tarbert on the south, forms part of Inverness - shire; Uig, Morsgail and Aline are included in Ross- shire. North Harris, joined to South Harris by the narrow isthmus at Tarbert, is bounded on the south by East and West Loch Tarbert, on the east by Loch Seaforb and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Its northern limit is formed partly by Loch Resort and partly by a land boundary much disputed in the past, passing from the head of Loch Resort between Stulaval and Rapaire to Mullach Ruisk and thence to the Amhuin a Mhuil near Aline Lodge on Loch Seaforth.