What About Classification Bias?: Channeling Sandy Berman F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Expand, Humanize, Simplify : an Interview with Sandy Berman Tina Gross St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Library Faculty Publications Library Services 2017 Expand, Humanize, Simplify : An Interview with Sandy Berman Tina Gross St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Sandy Berman retired, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Sanford Berman & Tina Gross (2017) Expand, Humanize, Simplify: An Interview with Sandy Berman, Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 55:6, 347-360, DOI: 10.1080/01639374.2017.1327468 This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expand, Humanize, Simplify : An Interview with Sandy Berman Sanford Berman & Tina Gross Sanford "Sandy" Berman is best known as an outspoken critic of the biases, omissions, and anachronisms of the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). He has inspired and challenged generations of catalogers to prioritize the needs of library users over deferential adherence to standards. His unrelenting efforts to improve and expand subject access for library users came to prominence with the 1971 publication of his seminal Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC Subject Heads Concerning People,1 written while Sandy was working at the University of Zambia. For over 25 years as the head cataloger at the Hennepin County Library (HCL), Sandy led a cataloging operation that devised and maintained its own subject headings system and pioneered practices designed to better facilitate access, often deviating from established standards. -

Three Decades Since Prejudices and Antipathies: a Study of Changes in the Library of Congress Subject Headings

Three Decades Since Prejudices and Antipathies: A Study of Changes in the Library of Congress Subject Headings Steven A. Knowlton ABSTRACT. The Library of Congress Subject Headings have been criticized for containing biased subject headings. One leading critic has been Sanford Berman, whose 1971 monograph Prejudices and Antipa- thies: A Tract on the LC Subject Heads Concerning People (P&A), listed a number of objectionable headings and proposed remedies. In the de- cades since P&A was first published, many of Berman’s suggestions have been implemented, while other headings remain unchanged. This paper compiles all of Berman’s suggestions and tracks the changes that have occurred; a brief analysis of the remaining areas of bias is included. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Ser- vice: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Berman, Sanford, 1933-; bias; subject cataloging; Li- brary of Congress Subject Headings Address correspondence to: Steven A. Knowlton, MLIS, 1356 Rambling Road, Ypsilanti, MI 48198 (E-mail: [email protected]). Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, Vol. 40(2) 2005 Available online at http://www.haworthpress.com/web/CCQ 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Digital Object Identifier: 10.1300/J104v40n02_08 123 124 CATALOGING & CLASSIFICATION QUARTERLY THE PROBLEM OF BIASED HEADINGS IN LCSH Since its first publication in 1909 as Subject Headings Used in the Dictionary Catalogues of the Library of Congress (Stone 2000), the Li- brary of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) have come under scrutiny by librarians. -

97/1/40 Personal Members Papers Sanford Berman Papers, 1933, 1942-1943, 1950-1953, 1959

97/1/40 Personal Members Papers Sanford Berman Papers, 1933, 1942-1943, 1950-1953, 1959- Box 1: AASL Conference; "Subject Headings as a Means of Access", 1986 "ABC's of Subject Headings...", New York Library Association Workshop, May 1, 1981 ABC-CLIO Information Services, 1985-87 Abidi, S.A.H., Makerere University, 1973, 1987 "Access to Alternatives: New Approaches in Cataloging", 1979-81 Africa by Fideler, 1981 Africa Report: Reviews, 1962-63 African Books in Print/ African Book Publishing Record (Hans Zell/ Abel), 1972-76 (See Box 14) "African Liberation Movements...", 1972-73 "African Magazines for American Libraries"/ Africana Library Journal, 1970-74 (See Box 14) African Studies Association/ Africana Libraries Newsletter/ ASR, 1972-76, 1986 Cataloging Subcommittee (Widenmann/Nyquist), 1974-81 ALA Annual Conference, 1973 Annual Conference, 1974 Midwinter Meeting, 1974 Midwinter Meeting, 1975 Conference Correspondence, Notes and Reports, 1973-86 1987-89 1990-92 Equality/ Sessions Awards, 1989-90 /RTSD, Catalog Code Revision Committee, 1974-76, 1986-89, 1993 /RTSD/CCS, Subject Analysis Committee, Program, 1979 Alabama Library Association Preconference, April 11, 1989 Alternative Acquisitions Project, 1978-80, 1983 Alternative Library Literature: 1982-83, 1982-83 Box 2: Alternative Library Literature: 1984-1985, 1986-89 1986-1987, 1987-90 (2 folders), 1988-92 "Alternative Library Literature" (LJ), 1977-78 Alternative Materials in Libraries, 1979-81 Alternative Papers (Temple University Press), 1980-83 Alternative Press Annual, 1982-87 Alternative Press Centre/ Alternative Press Index (Kathy Martin), 1973-89 1 97/1/40 "And Their Friends Ought to Be Us,"(Black Bart Brigade), 1972-73 Arizona "Advanced Cataloging Workshop", March 8-9, 1977 Arizona State Library Association Conference, 1984 Army Library Institute, 1980 Assistant Librarian: Letters, 1970 A/V Communications Association of Minnesota/ Minnesota Association of School Librarians, Joint Meeting, St. -

97/1/40 Personal Members Papers Sanford Berman Papers, 1933, 1942-1943, 1950-1953, 1959

97/1/40 Personal Members Papers Sanford Berman Papers, 1933, 1942-1943, 1950-1953, 1959- Box 1: AASL Conference; "Subject Headings as a Means of Access", 1986 "ABC's of Subject Headings...", New York Library Association Workshop, May 1, 1981 ABC-CLIO Information Services, 1985-87 Abidi, S.A.H., Makerere University, 1973, 1987 "Access to Alternatives: New Approaches in Cataloging", 1979-81 Africa by Fideler, 1981 Africa Report: Reviews, 1962-63 African Books in Print/ African Book Publishing Record (Hans Zell/ Abel), 1972-76 (See Box 14) "African Liberation Movements...", 1972-73 "African Magazines for American Libraries"/ Africana Library Journal, 1970-74 (See Box 14) African Studies Association/ Africana Libraries Newsletter/ ASR, 1972-76, 1986 Cataloging Subcommittee (Widenmann/Nyquist), 1974-81 ALA Annual Conference, 1973 Annual Conference, 1974 Midwinter Meeting, 1974 Midwinter Meeting, 1975 Conference Correspondence, Notes and Reports, 1973-86 1987-89 1990-92 Equality/ Sessions Awards, 1989-90 /RTSD, Catalog Code Revision Committee, 1974-76, 1986-89, 1993 /RTSD/CCS, Subject Analysis Committee, Program, 1979 Alabama Library Association Preconference, April 11, 1989 Alternative Acquisitions Project, 1978-80, 1983 Alternative Library Literature: 1982-83, 1982-83 Box 2: Alternative Library Literature: 1984-1985, 1986-89 1986-1987, 1987-90 (2 folders), 1988-92 "Alternative Library Literature" (LJ), 1977-78 Alternative Materials in Libraries, 1979-81 Alternative Papers (Temple University Press), 1980-83 Alternative Press Annual, 1982-87 97/1/40 2 Alternative Press Centre/ Alternative Press Index (Kathy Martin), 1973-89 "And Their Friends Ought to Be Us,"(Black Bart Brigade), 1972-73 Arizona "Advanced Cataloging Workshop", March 8-9, 1977 Arizona State Library Association Conference, 1984 Army Library Institute, 1980 Assistant Librarian: Letters, 1970 A/V Communications Association of Minnesota/ Minnesota Association of School Librarians, Joint Meeting, St. -

Sanford Berman Werk Und Wirken Eines Radical Librarian

Master Thesis im Rahmen des Universit¨atslehrganges Library and Information Studies MSc an der Universit¨at Wien in Kooperation mit der Osterreichischen¨ Nationalbibliothek Sanford Berman Werk und Wirken eines Radical Librarian zur Erlangung des Grades Master of Science eingereicht von Dr. Rainer Steltzer bei Mag. Markus Feigl Innsbruck, 2010 Zusammenfassung / Abstract Sanford Berman { Werk und Wirken eines Radical Librarian Seit der Ver¨offentlichung seines Buches Prejudices and antipathies (1971), ei- ner Abhandlung uber¨ tendenzi¨ose Terminologie in den Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH), ist Sanford Sandy\ Berman (geb. 1933) als lautstarker und " unermudlicher¨ Kritiker des bibliothekarischen Mainstream der USA bekannt. Die vorliegende Arbeit soll einen Uberblick¨ uber¨ Bermans Wirken als Bibliothekar und Aktivist bieten, darunter sein Bemuhen¨ um benutzerfreundlichere Kataloge, sein sozialer Aktivismus, sein Einsatz fur¨ alternative\ Materialien in Bibliotheken und " sein Engagement im Kampf gegen Zensur und die Kommerzialisierung von Biblio- theken. Das zentrale Kapitel der Arbeit ist Bermans bis heute andauernder Kritik an der Terminologie der LCSH gewidmet. Sanford Berman { a radical librarian's work and influence Since the publication (in 1971) of his book Prejudices and antipathies, a tract about biased terms in the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH), Sanford Sandy\ Berman (b. 1933) has been known as an outspoken and ceaseless critic " of mainstream American librarianship. This thesis aims to provide an overview of Berman's work as an activist librarian, including (but not limited to) his struggle for more user-friendly catalogs, his social activism, his advocacy for alternative\ " materials in libraries, and his campaigning against censorship and the commercia- lization of libraries. -

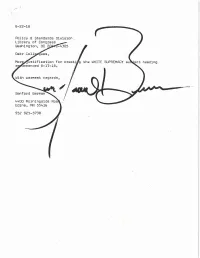

More Ustification Fur Creatifg the WHITE SUPREMACY Su Ect Heading Mmended 8-17-18. with Warmest Regards, Sanford Berman 4400

8-22-18 Policy & Standards Division Library of Congress Washington, DC 21 -4305 Dear Coll ■ ues, More ustification f❑r creatifg the WHITE SUPREMACY su ect heading mmended 8-17-18. With warmest regards, Sanford Berman 4400 Morningside Roa Edina, MN 55416 952 925-5738 WEDNESDAY August 22, 2018 ► n Racist speech inspires UNC students to topple Confederate monument By ANTONIA NO ORI FARZAN where we stand, less than the ground, according to the In 2011, Domby wrote a let- Washington Post ninety days perhaps after my Daily Tar Heel. Cheering and ter to the editor that was pub- return from Appomattox, I shouting, they began covering lished in the Daily Tar Heel, In 1913, Julian Carr, a prom- horsewhipped a Negro wench the statue with mud and dirt. quoting from Carr's speech inent industrialist and sup- until her skirts hung in shreds, Early Tuesday, the statue in hopes of adding some his- porter of the Ku Klux Klan, was because upon the streets of this was hauled away in a dump torical context to the debate. invited to speak at the unveil- quiet village she had publicly truck Activists picked it tip and ran ing of a statue of a Confeder- insulted and maligned a South- In recent yeais, Carr's with it, he said, making the rac- ate soldier on the campus of ern lady, and then rushed for speech has been a galvanizing ist language in the 1913 address the University of North Caro- protection to these University force for activists demanding a major issue in the campaign lina at Chapel Hill. -

Engaging an Author in a Critical Reading of Subject Headings

Perspective Engaging an Author in a Critical Reading of Subject Headings Amelia Bowen Koford ABSTRACT Most practitioners of critical librarianship agree that subject description is both valuable and political. Subject headings can either reinforce or subvert hierarchies of social domination. Outside the library profession, however, even among stakeholders such as authors, there is little awareness that librarians think or care about the politics of subject description. Talking about subject description with the authors whose works we hold and represent can strengthen our relationships, demystify our work, and hold us accountable for our practices. This paper discusses an interview I conducted with author Eli Clare about the Library of Congress Subject Headings assigned to his book, Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation. Clare describes feeling dismayed by and detached from the subject headings assigned to his book. He offers a sophisticated analysis of individual headings. He also reflects on the subject description project itself, using theories from genderqueer and transgender activism to discuss the limitations of categorization. Koford, Amelia. “Engaging an Author in a Critical Reading of Subject Headings.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1, no. 1 (2017). DOI: 10.24242/jclis.v1i1.20. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION Most practitioners of critical librarianship agree that subject description is both valuable and political. Outside the library profession, however, even among stakeholders such as authors, there is little awareness that librarians think or care about the politics of subject description. Talking about subject description with the authors whose works we hold and represent can strengthen our relationships, demystify our work, and hold us accountable for our practices. -

A Tribute from a PLG Cofounder (Harger) a Tributejrom a PLG Cofounder(Harger) 35 and Coordinated Activismamong Our New Colleagues

A Tributefrom a PLG Cofounder (Harger) 33 the articles being written in the first place. He seeks out submi.ssions his "Alternatives" column in Collection Buildingand suggests to library W .1· publishers possible topics and authors for new books. DIrect y or ~n- directly, Sandy inspires, provokes, and challenges many of the m- 'viduals who write critically about lihrarianship and, in doing this, he A Tribute from d1 h contributes a great deal more to the profession than a listing of all IS a Progressive Librarians own publications and public presentations might suggest: Berman's spirit has at times filtered through librarianship imperceptibly and on Guild Cofounder occasion broken through explosively. Ifhis influence were flower seeds there would be flowers popping out of books, catalogs, reference inter -Elaine Harger- views, and staff meetings in libraries across the country. In late June 1989 came my second encounter with Berman, this time in an American Library Association conference room in Dallas, My first encounter with Sandy Berman carne in the dim - but not Texas where a diverse group of of librarians was intensely debating yet dark - stacks of the School for Library Service Library at Columbia the "S~RT Guidelines for Librarians Interacting with South Africa." University. I was doing research on libraries and censorship in South My colleague Mark Rosenzweig and I, both recent graduates of Co Africa and had been led by Library Literature to the 1984/85 edition of lumbia's library school, went to this meeting curious to see how con Sanford Berman andJames P. Danky's Alternotioe Library Literature an troversial political issues were played out within ALA. -

2016 Bobcatsss Poster

The Search That Dare Not Speak Its Name: LGBT Information and Catalog Records Jessica Colbert University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Graduate School of Library & Information Science Introduction Findings Why is this Important? Controlled Vocabulary vs. Natural Language Improving subject headings for LGBT materials is Although the United States of America does not Library of Congress Subject Headings are a great beneficial for several reasons: have an official national library, our Library of way to collocate resources, but sometimes they do Congress acts as one. As such, the policies and not reflect the language patrons use to search, • Improved access procedures of the Library of Congress influence not especially in keyword searches. • Shaping societal attitudes only libraries across the country, but across the • Correct “aboutness” world. While the goal of the Library of Congress, and • “Sexual minorities” / “LGBT” thus libraries in our country, is to be objective and • “Transsexuals” / “Transgender” But these same reasons should also be applied to neutral, certain biases evolve. • Identities as plural nouns / Identities as singular other underserved communities and oppressed adjectives groups, as well as materials in general! In 1971, librarian and cataloger Sanford Berman • Absence of popular identities, e.g. queer published an influential text concerning bias in the Improved access, rich cataloging and classification, Library of Congress Subject Headings. This book, Besides a title or author search, the most common Art by Jessamyn West and socially conscious service are helpful for all titled Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC type of search in an OPAC is a keyword search, not materials. Subject Heads Concerning People, examines how a subject search. -

Social Responsibilities Round Table of the AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

Social Responsibilities Round Table OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTERnumber 133 December 1999 from the srrt coordinator: CANGreeting fellow SRRT Members. It is customary to begin one’s first message to you by thanking you for the opportunity to serve, that I am looking forward to the challenge and tasks at hand, and that I hope to hear from you with suggestions, ideas, comments, etc. However, there is something that is needed first. Wendy Thomas, who stepped down as SRRT Coordinator at the ALA Annual Meeting after serving two terms at the helm of this Round Table, deserves all of our thanks for her tenure in office. It is hopeful that as one accepts the challenge this position offers that it lands in the hands of a capable and caring person and a true leader. We were so blessed with Wendy. SRRT grew in many ways over the past two years and sometimes it was a rocky road over which the round table traveled. Looming over SRRT for several years has been an ongoing problem with our budget, a problem whose resolution began seeing light last year. While it is a problem with which we must still contend, Wendy and others have provided initial guidance and direction for us to follow. One of the task forces in SRRT was successful in achieving its own momentum and strength to take the next step in its growth, becoming the Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Round Table. Wendy helped in this process. Wendy leaves a legacy of leadership for SRRT. I like to think that she also leaves us a big, friendly, and warm smile and the simple word, “Hope,” as SRRT moves around the next meander in the river. -

AFRICANA LIBRARIES NEWSLETTER No

AFRICANA LIBRARIES NEWSLETTER No. 82, Aprii 1995 ISSN 0148-7868 Africana Libraries Newsletter (ALN) is published quarterly by the Michigan State University Libraries and the MSU Africa n Studies Center. Those copying contents are asked to citeAZJVas their source. ALN is produced to support the work of the Africana Librarians Council (ALC) of TABLE OF CONTENTS the African Studies Association. It carries the meeting minutes of ALC, CAMP (Cooperative Africana Microform Project) and other relevant groups. It also reports other items of interest to Editor’s Comments Africana librarians and those concerned about information resources about or in Africa. ACAL26 & Library Catalogs Editor: Joseph J. Lauer, Africana Library, MSU, East Lansing, MI 48824-1048. Acronyms Tel.: 517-355-1118; E-mail: [email protected]; Fax:517-432-1445. Deadline for no. 83: July 1, 1995; for no. 84: October 1, 1995. ALC/CAMP NEW S............................................2 Calendar Schedule for Evanston (May 1995) EDITOR’S COMMENTS Minutes of CAMP Meeting in Toronto (Nov. 1994) The core of this issue are the CAMP minutes, lightly edited, from the meeting last OTHER NEW S...................................................6 November. Other noteworthy items include reports on ALA in Philadelphia, a News from other Associations petition from Hennepin County, and the second edition of a one-page list of ALC Calendar regulars. Contributions came from many sources, including Ruby Bell-Gam, ALA/USIA Fellows Program Sanford Berman, Phyllis Bischof, Moore Crossey, Beverly Gray, Karen Fung, ALA reports: CC: AAM & CC:DA Nancy Schmidt, Mette Shayne, Janet Stanley, Ruth Thomas, and Tom Weissinger. Info Africa Nova Conference Free Materials Offered & Requested The completion of this issue was delayed by my attendance at the 26th Annual Resources at Libraries and Research Centers Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL), in Santa Monica, March 24-26.