C:\AAAA\Res Com Pdfs\WP11 Ohai.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda of Ohai Community Development Area Subcommittee

. . Contents 1 Apologies 2 Leave of absence 3 Conflict of Inter est 4 Public F orum 5 Extraordi nar y/Urgent Items 6 Confirmati on of Minutes Minutes of Ohai Communi ty D evelopment Ar ea Subcommittee 29/05/2018 . 7.1 Ohai H all update ☐ ☐ ☒ 1 The purpose of this report is to provide information about recent works undertaken at the Ohai Hall and to provide an update on the delays for consultation around retention of the Ohai Hall or Bowling Club building. 2 In 2005, the current Cleveland coal burner had a major recondition/overhaul carried out by C H Faul of Invercargill. The intention was that this would give another 15-20 years of life to the burner. 3 In 2015, it was suggested that there was an electrical fault and the burner was taken out of service with the wire being cut between the wall and the thermostat in the main hall and the burner unit. 4 The previous CDA had identified a project to upgrade the windows, paint the interior, install a zip and replace the LED lights. This was costed at approximately $40,000. 5 Subsequent to that decision being made the former Ohai Bowling Club building was gifted back to the community of Ohai and a decision was made to consult with the wider community about the comparative cost of upgrading and maintaining the Bowling Club and the Hall with a view to only keeping one building for use by the community. 6 In February 2018, at the first informal meeting of the new Ohai Community Development Area Subcommittee, the hall heating was identified as being a priority project for the Subcommittee and staff were requested to investigate alternative heating options. -

To: Southland District Council P O Box Invercargill [email protected]

To: Southland District Council P O Box Invercargill [email protected] From: Rosemary Penwarden C/- Counter Mail Blueskin Store 12 Orokonui Road Waitati Otago 03 4822831 [email protected] 25 February 2013 To Whom it May Concern Submission re Proposed Southland District Plan I do wish to be heard in respect of this submission. Introduction I grew up in rural New Zealand (North Island West Coast) and am a long-time resident of Otago, just up the road from Southland. In the past two years I have visited Southland many times, made new friends, seen much of the country and learned in detail about the proposed lignite developments in the Mataura valley. First and foremost I am a concerned citizen of this beautiful home of ours, planet Earth. I am a mother and grandmother, and carry my parental responsibility seriously. We do not have the right to pass on to our children a world in a state of climate chaos, economic and environmental disaster. For the world‟s climate to remain liveable, we must rapidly reduce the current level of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. The major source of such emissions is the burning of fossil fuels, and of these, coal is the most plentiful. Scientists have made it clear that coal must be phased out to give us any hope of avoiding runaway climate change. Lignite, as the dirtiest form of coal, must stay in the ground. Burning coal also contributes to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification is not an effect of climate change. It is related to a different receiving environment (seawater) and a different physical process (alteration of the chemical composition of the ocean rather than altering the heat trapping capacity of the atmosphere). -

No 6, 3 February 1955

No. 6 101 NEW ZEALAND THE New Zealand Gazette Published by Authori~ WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 3 FEBRUARY 1955 Land Held for Housing Purposes Set A.part for Purposes Land Held f01· a Public School Set A.part for Road. in Green Incidental to Coal-mining Operations in Block III, Wairio Island Bush Survey District Survey District [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE~ Governor-General [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE, Governor-General A PROCLAMATION A PROCLAMATION URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Lieutenant P General Sir Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928 and section 170 Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby proclaim and declare P of the Coal Mines Act 1925, I, Lieutenant-General Sir that the land described in the Schedule hereto now held for a Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the Governor-General of public school is hereby set apart for road; and I also declare New ZeaJand, hereby proclaim and declare that the surface that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the of the land described in the Schedule hereto, together with 7th day of February 1955. the subsoil above a plane 100 ft. below and approximately parallel to the surface of the said land now held for housing purposes, is hereby set apart for purposes incidental to coal SCHEDULE mining operations; and I also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the 7th day of February 1955. APPROXIMATE areas of the pieces of land set apart: A. R. P. Being 0 0 3 · 2 Part Section 37. -

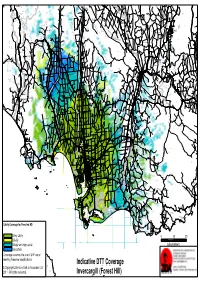

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

1274 the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

1274 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 38 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 267348 Robertson, Alexander Fraser, railway employee, Tahakopa, 376237 Shanks, John (jun.), farm-manager, Warepa, South Otago. South Otago. 060929 Shanks, Stuart, farm hand, Waikana, Ferndale Rural 281491 Robertson, Alexander William, shepherd, "Warwick Delivery, Gore. Downs," Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. 397282 Sharp, Charles, farmer, Tuapeka Mouth. 257886 Robertson, Alfred Roy, labourer, 152 Spay St., Invercargill. 426037 Shaw, Ivan Holden, paper-mill employee, Oakland St., 203202 Robertson, Douglas Belgium, labourer, Roxburgh. Mataura. 262523 Robertson, Eric James, farmer, Heddon Bush Rural Deli very, 282484 Shaw, John, N.Z.R. employee, care of New Zealand Railways, Winton. Milton, South Otago. 151974 Robertson, Francis William, Ellis Rd., care of Public 421302 Shaw, William Martin, farm hand, Orepuki. W arks, W aikiwi, Invercargill. 066560 Shearer, George, quarryman, care of G. Hawkins, \Vinton. 097491 Robertson, James Ian, wool-sorter, Awarua Plains Post 116926 Sheat, Robert Davy, teamster, Moneymore Rural Delivery, office, Southland. Milton. 423543 Robertson, Menzie Athol, labourer, Woodend, Southland.- 253436 Shedden, Allen Miller, coal-trucker, Nightcaps. 298971 Robertson, Robert Alexander, dairy-farmer, Wright's Bush 252526 Sheddan, Maurice, farm labourer, Gore, \Vail,aka Rural Gladfield Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Delivery. 294830 Robertson, Struan Malcolm, labourer, Awarua Plains, 283883 Sheddan, Robert Bruce, farm hand, Scott's Gap, Otautau Southland. Rural Delivery. 431165 Robertson, Tasman Harrie, labourer, 215 Bowmont St., 010254 Sheehan, Walter, general labourer, Te Tipua Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Gore. 247092 Robertson, William Douglas, fisherman, Half-moon Bay, 280428 Sheehan, Walter James, farm hand, Te Tua, Riverton Rural Stewart Island. -

The New Zealand Gazette. 331

JAN. 20.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 331 MILITARY AREA No, 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No.· 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oontinued. 499820 Irwin, Robert William Hunter, mail-contractor, Riversdale, 532403 Kindley, Arthur William,·farm labourer, Winton. Southland. 617773 King, Duncan McEwan, farm hand, South Hillend Rural 598228 Irwin, Samuel David, farmer, Winton, Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. Delivery, Brown. 498833 King, Robert Park, farmer, Orepuki, Rural Delivery, 513577 Isaacs, Jack, school-teacher, The School, Te Anau. Riverton-Tuatapere. 497217 Jack, Alexander, labourer, James St., Balclutha. 571988 King, Ronald H. M., farmer, Orawia. 526047 Jackson, Albert Ernest;plumber, care of R. G. Speirs, Ltd., 532584 King, Thomas James, cutter, Rosebank, Balclutha. Dee St., Invercargill. 532337 King, Tom Robert, agricultural contractor, Drummond. 595869 James, Francis William, sheep,farmer, Otautau. 595529 Kingdon, Arthur Nehemiah, farmer, Waikaka Rural De. 549289 James, Frederick Helmar, farmer, Bainfield Rd., Waiki.wi livery, Gore. West Plains Rural Delivery, Inveroargill, 595611 Kirby, Owen Joseph, farmer, Cardigan, Wyndham. 496705 James, Norman Thompson, farmer, Otautau, Aparima 571353 Kirk, Patrick Henry, farmer, Tokanui, Southland. Rural Delivery, Southland. 482649 Kitto, Morris Edward, blacksmith, Roxburgh. 561654 Jamieson, Thomas Wilson, farmer, Waiwera South. 594698 Kitto, Raymond Gordon, school-teacher, 5 Anzac St., Gore. 581971 Jardine, Dickson Glendinning, sheep-farmer, Kawarau Falls 509719 Knewstubb, Stanley Tyler, orchardist, Coal Creek Flat, Station, Queenstown. Roxburgh. , 580294 Jeffrey, Thomas Noel, farmer, Wendonside Rural Delivery, 430969 Knight, David Eric Sinclair, tallow assistant, Selbourne St. Gore. Mataura. 582520 Jenkins, Colin Hendry, farm manager, Rural Delivery, 467306 Knight, John Havelock, farmer, Riverton, Rural Delivery, · Balclutha. Tuatapere. 580256 Jenkins, John Edward, storeman - timekeeper, Homer 466864 Knight, Ralph Condie, civil servant, 83 Ohara St., Inver. -

Agenda of Nightcaps Community Development Area Subcommittee

. . Contents 1 Apologies 2 Leave of absence 3 Conflict of Inter est 4 Public F orum 5 Extraordi nar y/Urgent Items 6 Confirmati on of Minutes Minutes of Nightcaps C ommunity Devel opment Area Subcommi ttee 12/03/2019 . 7.1 Council R eport ☐ ☐ ☒ 1. In mid-April the Ministry of the Environment (MFE) released Environment Aotearoa 2019, which is a national state of the environment report released every three years. A copy of the latest report is available on the MFE website (www.mfe.govt.nz/environment-aotearoa-2019). 2. The purpose of the report is to present ‘a diagnosis of the health of the environment’ so that there is a clear understanding of the changes which are occurring in the environment and the reasons for those changes. It does this using a framework that provides an outline of the current state, what has contributed to the changes that have occurred, what the consequences of the changes are and where there are gaps in the knowledge base. The last full report was produced in 2015 and prior to that, and a change in legislation, versions were produced in 2007 and 1997. 3. The report identifies an ongoing decline in the overall state of the environment but identifies the following priority environmental issues as being of greatest concern: our native plants, animals and ecosystems are under threat. changes to the vegetation on our land are degrading the soil and water. urban growth is reducing versatile land and native biodiversity. our waterways are polluted in farming areas. our environment is polluted in urban areas. -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

Tuatapere-Community-Response-Plan

NTON Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used as warnings for a Civil Defence emergency) Tuatapere Community Response Plan 2018 If you’d like to become part of the Tuatapere Community Response Group Please email [email protected] Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz Community Response Planning In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. The more prepared a community is, the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of Tuatapere, information about key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Tuatapere Community Response Group have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southland’s first point of community contact in an emergency. Demographic details • Tuatapere is contained within the Southland District Council area; • The Tuatapere area has a population of approximately 1,940. Tuatapere has a population of about 558; • The main industries in the area include agriculture, forestry, sawmilling, fishing and transportation; • The town has a medical centre, ambulance, police and fire service. There are also fire stations at Orepuki and Blackmount; • There are two primary schools in the area. Waiau Area School and Hauroko Primary School, as well as various preschool options; • The broad geographic area for the Tuatapere Community Response Plan includes lower southwest Fiordland, Lake Hauroko, Lake Monowai, Blackmount, Cliften, Orepuki and Pahia, see the map below for a more detailed indication; • This is not to limit the area, but to give an indication of the extent of the geographic district. -

Bullinggillianm1991bahons.Pdf (4.414Mb)

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 Preventable deaths? : the 1918 influenza pandemic in Nightcaps Gillian M Bulling A study submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honours at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. 1991 Created 7/12/2011 GILLIAN BULLING THE 1918 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC IN NIGHTCAPS PREFACE There are several people I would like to thank: for their considerable help and encouragement of this project. Mr MacKay of Wairio and Mrs McDougall of the Otautau Public Library for their help with the research. The staff of the Invercargill Register ofBirths, Deaths and Marriages. David Hartley and Judi Eathorne-Gould for their computing skills. Mrs Dorothy Bulling and Mrs Diane Elder 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures 4 List of illustrations 4 Introduction , 6 Chapter one - Setting the Scene 9 Chapter two - Otautau and Nightcaps - Typical Country Towns? 35 Chapter three - The Victims 53 Conclusion 64 Appendix 66 Bibliography 71 4 TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS Health Department Notices .J q -20 Source - Southland Times November 1918 Influenza Remedies. -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Dan Davin Re-Visited

40 Roads Around Home: Dan Davin Re-visited Denis Lenihan ‘And isn’t history art?’ ‘An inferior form of fiction.’ Dan Davin: The Sullen Bell, p 112 In 1996, Oxford University Press published Keith Ovenden’s A Fighting Withdrawal: The Life of Dan Davin, Writer, Soldier, Publisher. It is a substantial work of nearly 500 pages, including five pages of acknowledgements and 52 pages of notes, and was nearly four years in the making. In the preface, Ovenden makes the somewhat startling admission that ‘I believed I knew [Davin] well’ but after completing the research for the book ‘I discovered that I had not really known him at all, and that the figure whose life I can now document and describe in great detail remains baffingly remote’. In a separate piece, I hope to try and show why Ovenden found Davin retreating into the distance. Here I am more concerned with the bricks and mortar rather than the finished structure. Despite the considerable numbers of people to whom Ovenden spoke about Davin, and the wealth of written material from which he quotes, there is a good deal of evidence in the book that Ovenden has an imperfect grasp of many matters of fact, particularly about Davin’s early years until he left New Zealand for Oxford in 1936. The earliest of these is the detail of Davin’s birth. According to Ovenden, Davin ‘was born in his parents’ bed at Makarewa on Monday 1 September 1913’. Davin’s own entry in the 1956 New Zealand Who’s Who records that he was born in Invercargill.