Scoping a New Forestry Plan for Forests and Woodland in West Tyrone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish of Ardstraw West and Castlederg

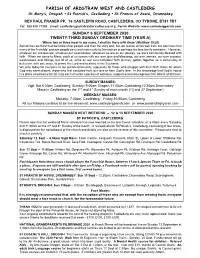

PARISH OF ARDSTRAW WEST AND CASTLEDERG St Mary’s, Dregish St Patrick’s, Castlederg St Francis of Assisi, Drumnabey REV PAUL FRASER PP, 16 CASTLEFIN ROAD, CASTLEDERG, CO TYRONE, BT81 7BT Tel: 028 816 71393 Email: [email protected] Parish Website: www.castledergparish.com SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER 2020 TWENTY-THIRD SUNDAY ORDINARY TIME (YEAR A) ‘Where two or three meet in my name, I shall be there with them’ (Matthew 18:20) Sometimes we think that we know other people and their life story well, but we realise all too well from our own lives that many of the ‘invisible’ crosses people carry are known only to themselves or perhaps to close family members. However, whatever our crosses are, whatever our weaknesses, wherever we are on our journey, we are a community blessed with faith. When we come to Mass, each of us comes with our own joys and blessings, our own worries, our own crosses, weaknesses and failings, but all of us, while on our own individual faith journey, gather together as a community of believers, with one voice, to praise the Lord and to share in the Eucharist. We pray today for everyone in our parish community, especially for those who struggle with their faith, those for whom God may seem distant, those who feel excluded from our love or from God’s love. In the knowledge that God’s House is a place of welcome for all, may each of us be a person of welcome, support and encouragement for others at all times. h SUNDAY MASSES: Vigil: Sat 6.00pm Castlederg. -

Exploring the History & Heritage of Tyrone and the Sperrins

Exploring the History & Heritage of Tyrone and The Sperrins Millennium Sculpture Strabane Canal Artigarvan & Leckpatrick Moor Lough Lough Ash Plumbridge & The Glenelly Valley The Wilson Ancestral Home Sion Mills Castlederg Killeter Village Ardstraw Graveyard Stewart Castle Harry Avery’s Castle Patrick Street Graveyard, Strabane pPB-1 Heritage Trail Time stands still; time marches on. It’s everywhere you look. In our majestic mountains and rivers, our quiet forests and rolling fields, in our lively towns and scenic villages: history is here, alive and well. Some of that history is ancient and mysterious, its archaeology shaping our landscape, even the very tales we tell ourselves. But there are other, more recent histories too – of industry and innovation; of fascinating social change and of a vibrant, living culture. Get the full Local visitor App experience: information: Here then is the story of Tyrone and the Sperrins - Download it to your iphone The Alley Artsan and extraordinary journey through many worlds, from or android smartphone Conference Centre 1A Railway Sdistanttreet, Str pre-historyabane all the way to the present day. and discover even more Co. Tyrone, BT82 8EF about the History & Heritage It’s a magical, unforgettable experience. of Tyrone and The Sperrins. Email: [email protected] Web:www.discovertyroneandsperrins.com Tel: (028) 71Join38 4444 us and discover that as time marches on, time also stands still… p2-3 x the sites The sites are categorised 1 Millennium Sculpture 6 by heritage type as below 2 Strabane Canal 8 -

![Parts of County Tyrone - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2650/parts-of-county-tyrone-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-1922650.webp)

Parts of County Tyrone - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

Parts of County Tyrone - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record Townland Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Superintendent Dispensary/Loc. District Electoral No. Registrar's District Reg. District Division [DED] 1911 1172 Aghaboy Lower Bodoney Lower Strabane Upper Gortin/Omagh Gortin Fallagh 1173 Aghaboy Upper Bodoney Lower Strabane Upper Gortin/Omagh Gortin Fallagh 987 Aghabrack Donaghedy Strabane Lower Gortin/Strabane Plumbridge Stranagalwilly 315 Aghacolumb Arboe Dungannon Upper Cookstown Stewartstown Killycolpy 1346 Aghadarragh Dromore Omagh East Omagh Dromore Dromore 664 Aghadreenan Donacavey [part of] Omagh East Omagh Fintona Tattymoyle 680 Aghadulla Drumragh Omagh East Omagh Omagh No. 1 Clanabogan 1347 Aghadulla (Harper) Dromore Omagh East Omagh Dromore Camderry 236 Aghafad Pomeroy Dungannon Middle Cookstown Pomeroy Pomeroy 871 Aghafad Ardstraw [part of] Strabane Lower Strabane Newtownstewart Baronscourt 988 Aghafad Donaghedy Strabane Lower Gortin/Strabane Plumbridge Loughash 619 Aghagallon Cappagh [part of] Omagh East Omagh Six Mile Cross Camowen 766 Aghagogan Termonmaguirk [part of] Omagh East Omagh Omagh No. 2 Carrickmore 1432 Aghakinmart Longfield West Omagh West Castlederg Castlederg Clare 288 Aghakinsallagh Glebe Tullyniskan Dungannon Middle Dungannon Coalisland Tullyniskan 1228 Aghalane Bodoney Upper Strabane Upper Gortin/Strabane Plumbridge Plumbridge 1278 Aghalane Cappagh [part of] Strabane Upper Omagh Omagh No. 2 Mountfield 36 Aghalarg Donaghenry Dungannon Middle Cookstown Stewartstown Stewartstown -

Parish of Ardstraw West and Castlederg

PARISH OF ARDSTRAW WEST AND CASTLEDERG St Mary’s, Dregish St Patrick’s, Castlederg St Francis of Assisi, Drumnabey REV PAUL FRASER PP, 16 CASTLEFIN ROAD, CASTLEDERG, CO TYRONE, BT81 7BT Tel: 028 816 71393 Email: [email protected] Parish Website: www.castledergparish.com SUNDAY 27 SEPTEMBER 2020 TWENTY-SIXTH SUNDAY ORDINARY TIME (YEAR A) In the Parable of the Two Sons that we hear today (Matthew 21:28-32), the saying with which we are all familiar, ‘actions speak louder than words’ is the core message of Jesus. In this parable, neither son does what he says he will do, but the first son then re-thinks his initial decision and goes to the vineyard, as asked by his father. The ability to change our mind is an essential element of all healthy relationships. A mind that is closed to change – for example, one that refuses to admit to mistakes, one that refuses to apologise and change ways – lacks the virtue of humility. It can destroy relationships. We think today of any relationships in our lives that remain fractious because of our inability to change our mind – perhaps our inability to admit to our own weaknesses and address them or our inability to drop a grudge or forget a wrongdoing. Act today: ‘The first to apologise is the bravest, the first to forgive is the strongest, the first to forget is the happiest’ SUNDAY MASSES: Vigil: Sat 6.00pm Castlederg. Sunday: 9.00am Dregish,11.00am Castlederg,12.30pm Drumnabey Mass in Castlederg on the 2 nd and 4 th Sunday of each month (13 & 27 Sept, 11 & 25 Oct) WEEKDAY MASSES: Monday: 7.30pm, Castlederg, Friday:10.00am, Castlederg All our Masses continue to be live-streamed: www.castledergparish.com or www.parishofaghyaran.com SUNDAY MASSES NEXT WEEKEND – 3 & 4 OCTOBER 2020 ST PATRICK’S, CASTLEDERG: Saturday 3 October – 6.00pm Vigil Mass : Group C - Killeter Road, Dergview Park, Alexander Park, Ashburn Park, Kilclean Road, Ashleigh Court, Oakleigh Grove, Kilcroagh Road, Cavan Road, Whiterock Park, Mucklehill View, Kilcurragh Park, Greystone Avenue, Moneygal Road, Pollyarnon Road. -

Appeals Schedule Derry City and Strabane District

Appeals Schedule Derry City and Strabane District Please Note: Applications are listed in order received by PAC Appendix 12 CURRENT APPEALS Reference PAC Appeal Type Proposal Location Applicant Summary Update Appeal Status Number reference 1 EN/2016/0199 2017/E0040 Appeal against Alleged unauthorised Buildings and Michael Enforcement Notice Decision received 20 Enforcement change of use of land to land at 15 McGonagle Appeal November 2018 Notice Issued a clothes recycling Beragh Hill Road, Enforcement Notice facility; of buildings and Ballynagalliagh, Upheld land for the storage of Londonderry materials, storage containers, vehicles and trailers; of a dwelling to flats; and of an outbuilding to a dwelling 2 LA11/2018/0160/DE 2018/C004 Appeal on EIA Proposed restoration by Lisbunny Quarry, W & J Delegated Decision Decision received 15 TEIA Determination infilling with inert waste Longland Road, Chambers to request November 2018 of Lisbunny Quarry, Claudy Environmental Decision upheld - ES Longland Road, Claudy Statement required 3 LA11/2015/0137/CA 2018/E0018 Appeal against Alleged unauthorised Land and Mr John Quinn Enforcement Notice Decision received 15 Enforcement erection of buildings premises at 69 Appeal November 2018 Notice Issued and change of use of Peacock Rd BT82 Enforcement Notice the land and buildings 9NP, Sion Mills, Terms Varied for a manufacturing Tyrone workshop Appeals Schedule Derry City and Strabane District Please Note: Applications are listed in order received by PAC Appendix 12 4 LA11/2017/0085/CA 2018/E0024 Appeal against Alleged unauthorised Lands at former Mr David Enforcement Notice Enforcement Notice Enforcement use of land for the Drumahoe Gilmore Appeal Quashed notice issued deposition of controlled Industrial Estate, waste (as defined in the Drumahoe Road, Waste and Ardnabrocky, Contaminated Land (NI) Londonderry. -

FOI-1083-FOI-Strabane-Cemeteries

Cemeteries Strabane Area SITE NAME SITE LOCATION POSTCODE ACTIVE CEMETERIES AUGHALANE CEMETERY GLENELLY ROAD, PLUMBRIDGE BT79 8AE ARDSTRAW NEW MAGHERACOLTON RD, NEWTOWNSTEWART BT78 4LF CEMETERY CASTLEDERG CEMETERY DRUMQUIN ROAD, CASTLEDERG BT81 7RB MOUNTCASTLE CEMETERY DUNCASTLE ROAD, DONEMANA BT82 0LR STRABANE CEMETERY MILLTOWN ROAD, STRABANE BT78 4NA URNEY(NEW) CEMETERY URNEY ROAD, STRABANE BT82 9RP ARDSTRAW PARISH MAIN STREET, NEWTOWNSTEWART BT78 4AD CHURCH CEMETERY (not council owned but active) CLOSED- BUT MAINTAINED ARDSTRAW (OLD) URBALREAGH ROAD, NEWTOWNSTEWART BT78 4LR CEMETERY BADONEY CEMETERY GLENELLY ROAD, PLUMBRIDGE BT79 8BP CAMUS CEMETERY LISKEY ROAD, VICTORIA BRIDGE BT82 8NR CHURCH OF IRELAND MAIN STREET, CASTLEDERG BT81 7AS CEMETERY, CASTLEDERG CORRICK CEMETERY PLUMBRIDGE ROAD, NEWTOWNSTEWART BT78 4DP WORK HOUSE PAUPERS DERRY ROAD DEPOT, COUNCIL OFFICES BT82 8DY CEMETERY CRANAGH CEMETERY PARK ROAD, CRANAGH BT79 8LP DONAGHEADY CEMETERY CASTLEWARREN ROAD, DONEMANA BT82 0PJ GRANGE CEMETERY GRANGE ROAD, BREADY BT82 0DT LECKPATRICK CEMETERY BALLYHEATHER ROAD, BALLYMAGORRY BT82 0BD MAGHERAKEEL CEMETERY MAGHERAKEEL ROAD, KILLETER BT81 7HA PATRICK STEET CEMETERY PATRICK STREET, STRABANE BT82 8DG PUBBLE CEMETERY GNR WAY, NEWTOWNSTEWART BT78 4NQ (Bunderg Rd -Nearest) SCARVAHERIN CEMETERY SCARVAHERIN ROAD, CASTLEDERG BT78 7NW URNEY CEMETERY(OLD) URNEY RD STRABANE BT82 9RU SITE NAME STATUS BURIALS TO DATE AS AT DECEMBER 2016 BURIALS AVAILABLE PLOTS ESTIMATED - INFORMATION TAKEN FROM BURIAL JAN- DEC AS AT DECEMBER CAPACITY PER PLOT REGISTERS -

Title of Report: Rural Development Programme

Title of Report: Officer presenting: Rural Development Head of Business Programme - International Author: Rural Development Programme Manager Appalachian Trail 1. Purpose of Report/Recommendations 1.1 To seek Members' approval for Council to act as lead partner for a joint Rural Co- operation project on the International Appalachian Trail (IAT) and feasibility study as part of the NI Rural Development Programme 2014-2020 and to update Members on a recent IAT best practice visit to Scotland. 2. Background 2.1 Members may recall a paper presented in June 2016 in respect of future development of the International Appalachian Trail (IAT) and approval to investigate funding opportunities, including through the Rural Development programme. 2.2 The International Appalachian Trail is a walking/hiking route based on the original Appalachian Mountains, which after continental drift, remnants ended up in eastern United States, eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the British Isles, Ireland, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. The route started in US and Canada and extended to Europe, with the IAT Ireland section formally launched in 2013. When expansion is complete, the IAT will be the largest trail network and one of the largest outdoor adventure brands in the world and is recognised as a key potential driver for rural economic development. 2.3 The Ireland chapter of the trail runs from west Donegal to Larne. The route largely follows the existing Ulster way and takes in County Donegal as well as five council areas in Northern Ireland (Derry City & Strabane District, Fermanagh & Omagh, Mid Ulster, Causeway Coast & Glens and Mid & East Antrim). -

Tír Eoghain 2009

Tír Eoghain 2009 Lámh-Leabhar agus Clár na gClúichí Tír Eoghain 2009 Lámh-Leabhar agus Clár na gClúichí A n An Coiste Bainisti 2009 C o Cathaoirleach Pádraig Ó Dorchai i s Pat Darcy t e 86 Tattyreagh Rd B Tattyreagh, Omagh a i Mobile No. 07712873386 n i [email protected] s t i 2 Leas Cathaoirleach Ciarán Mac Lochlainn 0 0 Ciaran McLaughlin 9 9 Rosevale Sion Mills, Strabane Telephone No. 81658762 Mobile No. 07894642984 [email protected] Rúnaí Damhnaic Mac Eochaidh Dominic McCaughey 11 Effernan Rd, Trillick Telephone No. 8956 1501 Mobile No. 07711762529 Co. Board Office 8225 7573 [email protected] Leas Rúnaí Micheál Mac Eochaidh Michael McCaughey 30 Berkley Heights, Killyclogher, BT79 7PR Telephone No. 82252448 Mobile No. 07775576895 3 Tír Eoghain 2009 Lámh-Leabhar agus Clár na gClúichí 9 0 An Coiste Bainisti 2009 0 2 Cisteoir Micheál Ó hAirmhí i t Michael Harvey s i Altnascaire n i a Omagh Rd, B Pomeroy e t Telephone No. 8775 8855 s i Mobile No. 07733128220 o C [email protected] n A Leas Cisteoir Séamus Mac Dónaill Seamus McDonald 123 Carrigans Rd, Omagh Telephone No. 8224 2655 Mobile No. 07764928760 Ard-Chomhairle Breandán Ó hEarcáin Brendan Harkin 74 Tiquin Rd, Killyclogher Omagh Telephone No. 8224 4522 Mobile No. 07825271800 Comhairle Uladh Cuthbert Ó Donnaile Cuthbert Donnelly 25 Lisgenny Rd, Aughnacloy Telephone No. 8555 7385 Mobile No. 07803150347 4 Tír Eoghain 2009 Lámh-Leabhar agus Clár na gClúichí A n An Coiste Bainisti 2009 C o Comhairle Uladh Liam Mac Niallais i s Liam Nelis t e 3 Knockmore Drive, B Dungannon a i Telephone No. -

List of Decisions Issued

Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 9/1/2017 12:00:00To: 9/29/2017 AM 12:00:00 AM No. of Applications: 97 Reference Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Date Time to Number Decision Process Issued (Working Days) A/2013/0507/F Genova North West Ltd C/o Unit 4 Application to vary Condition 6 of Permission 9/15/17 988 Agent Crescent Link Retail Park A/1996/0505 and Condition 4 of Granted Waterside A/2001/0098/RM to allow mixed Londonderry retailing A/2014/0538/F Paul Heaney 49 Upper 49 Upper Galliagh Road 20 no pitches for touring Permission 9/12/17 717 Galliagh Road Derry motorhomes, caravans or tents to Granted Derry include electric hook ups (amended site). J/2012/0277/F Mr T.J. Gillespie 14 Crilly's Hill Leitrim Hill Non compliance with condition Permission 9/12/17 1,274 Killeter Aghnadoo Road no. 02 of planning permission J/ Granted Castlederg Killeter 2007/0719/F to allow extraction BT81 7EW Castlederg to take place beyond December Co. Tyrone 2012. J/2013/0264/O Mr A Harley c/o Agent Approx 120m west of 110 Proposed dwelling and domestic Permission 9/28/17 999 Culvacullion Road garage Granted Plumbridge Page 1 of 23 Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 9/1/2017 12:00:00To: 9/29/2017 AM 12:00:00 AM No. of Applications: 97 Reference Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Date Time to Number Decision Process Issued (Working Days) LA11/2015/0110/F Cardtronics UK Ltd T/A Castlebet Ltd 113 Melmount Remove 3 existing glazing panels Permission 9/12/17 589 Cashzone P.O. -

Chief Executive

STRABANE IN WORLD WAR 1 As reported in The Strabane Chronicle & The Strabane Weekly News July 1914 – November 1919 Thanks are due to all those who contributed to the compilation of material for this research project. The group painstakingly combed the microfilm copies of the Strabane Chronicle and Strabane Weekly news and selected material and these included John Rogan, James Johnston, Joseph O’Kane, Hugh McGarrigle, Kathleen Patton, Chris McDermott, Pat McGuigan, William Allen, Ronnie Johnston, Michael Kennedy and John Dooher. Thanks are also due to Ms Geraldine Casey for her assistance. The group is grateful to the staff of Strabane Library for their unfailing help and to Libraries N.I. for making the resources available. Photo on front cover shows a military parade at The Diamond, Lifford, in 1914. CONTENTS 1914 page 4 1915 page 34 1916 page 146 1917 page 240 1918 page 318 1919 page 416 1914 Strabane Chronicle 4th July 1914 RURAL LABOUR PROBLEM There has been for many years the report states a marked scarcity of agricultural labourers, which was becoming more and more acute. The increase in the cost of living and the increased prices which the farmers was getting for his produce had been mainly instrumental in bringing about increased wages. The wages however are still very low. The usual daily wage current in 1913 were for men 2s to 3s 6d, for women 1s 6d to 3s. RESERVES CALLED UP IMMEDIATELY At the start of WW1 58,000 Irishmen were already enlisted in the British Regular Army or Navy – 21,000 serving regular soldiers, 18,000 reservists, 12,000 in the Special Reserve, 5,000 Naval ratings and 2,000 officers. -

Scheduled Historic Monuments Of

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT DIVISION Historic Monuments of Northern Ireland Scheduled Historic Monuments 1st April 2016 NORTHERN IRELAND ENVIRONMENT AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT HISTORIC MONUMENTS OF NORTHERN IRELAND Historic Environment Division identifies, protects, records, investigates and presents Northern Ireland's heritage of archaeological and historic sites and monuments. The Department has statutory responsibility for the sites and monuments in this list which are protected under Article 3 of the Historic Monuments and Archaeological Objects (NI) Order 1995. They are and are listed in alphabetical order of townland name within each county. The Schedule of Historic Monuments at April 2016 This schedule is compiled and maintained by the Department and is available for public consultation at the Monuments and Buildings Record, Waterman House, 5-33 Hill Street, Belfast BT1 2LA. Additions and amendments are made throughout each year and this list supersedes all previously issued lists. To date there are 1,977 scheduled historic monuments. It is an offence to damage or alter a scheduled site in any way. No works should be planned or undertaken at the sites listed here without first consulting with Historic Environment Division and obtaining any necessary Scheduled Monument Consent. The unique reference number for each site is in the last column of each entry and should be quoted in all correspondence. Where sites are State Care and also have a scheduled area they are demarcated with an asterisk in this list The work of scheduling is ongoing, and the fact that a site is not in this list does not diminish its unique archaeological importance. The Northern Ireland Sites and Monuments Record (NISMR) has information on some 16,656 sites of which this scheduled list is about 12% at present. -

Visitor Guide

Ranfurly House Arts & Flavour of Visitor Centre Tyrone Opening Hours: Stay, Explore, Enjoy April to September 9.00am – 9.00pm Saturday 9.00am – 5.00pm Sunday 1.00pm – 5.00pm October to March Monday - Saturday 9.00am – 5.00pm Sunday -Closed Services we provide: Visitor • A wide range of Information on the local area (including places to visit, places to eat, activities and accommodation) • Shop area with maps, guidebooks and local historical Guide Information. • Full access for disabled users Hill of The O’Neill & Ranfurly House Arts & Visitor Centre 26 Market Square, Dungannon, Co Tyrone, BT70 1AB T: (028) 8772 8600 E: [email protected] W: www.dungannon.info Flavour of Tyrone Ltd Killymaddy Centre, 190 Ballygawley Road, Dungannon, Co Tyrone BT70 1TF T: (028) 8776 7259 E: info@flavouroftyrone.com W: www.flavouroftyrone.com Disclaimer: While every care has been taken to ensure that all information is correct at time of going to print no responsibility can be accepted for omission or error. Photography provided by Flavour of Tyrone members, Northern Ireland Tourist Board, Jim Kerr Photography, Dungannon, Brian Morrison Photography, Belfast. Some text by Cathal Coyle, Little Book of Tyrone. Flavour of Tyrone Stay, Explore, Enjoy FREE COPY The project is part funded by Dungannon & South Tyrone Borough Council, Invest Northern Ireland and the European Regional Development Fund under the Sustainable Competitiveness Programme for Northern Ireland. St Patrick’s Chair & Well, Augher CONTENTS Visitor Attractions & Heritage Sites 03 Walking, Driving & Cycling Tours 20 Activities 28 Learn To Tyrone Activities 37 Events 44 Entertainment, Arts 47 Tyrone Good Food Circle 52 Food Producers 66 Crafts 73 Shopping 80 Towns & Villages 83 Accommodation 85 Information & Services 110 Flavour of Tyrone Ulster American Folk Park Stay, Explore, Enjoy If there’s one thing about Tyrone, you’re never too far away from a heritage trail, heritage site, visitor centre or park.