Case Australian Wine (A) – a Global Challenger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRALIA > Australia

Endeavour Group Limited. ABN: Page 1 of 7 Untitled Document All sales subject to the conditions printed in this catalogue Created on: 30/09/2021 6:17:26 PM HX825 - Explore NSW & ACT 9:00 PM Tuesday, June 9, 2015 A Buyers Premium of 15% excluding GST applies to all lots. All lots sold GST inclusive, except where marked '#'. AUSTRALIA > Australia A-E Lot No Description Vintage Quantity Bottle Winning Price Classification 1 ANGULLONG Taplow Maze Cabernet, Central Ranges. Screwcap Closure. 2011 2 Bottle Passed In 2 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2013 1 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 3 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 2 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 4 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 3 Bottle $10.0000000000 Closure. 00000000 5 BRINDABELLA HILLS WINERY Riesling, Canberra District. Screwcap 2014 6 Bottle Passed In Closure. 6 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 1 Bottle $120.000000000 Exceptional 000000000 7 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Minor 1996 1 Bottle Passed In Exceptional Label Stain/s. 8 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 2 Bottle Passed In Exceptional 9 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 1996 2 Bottle Passed In Exceptional 10 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. Minor 1996 3 Bottle Passed In Exceptional Label Stain/s. 11 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 2001 1 Bottle $84.0000000000 Exceptional 00000000 12 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. 2001 2 Bottle $76.0000000000 Exceptional 00000000 13 BROKENWOOD WINES Graveyard Vineyard Shiraz, Hunter Valley. -

Total Entries 2006 Competition

Page 1 TOTAL ENTRIES 2006 COMPETITION WINERY PARTICULAR NAME VINT MAIN GRAPE & % OTHERS & % STATE 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CABERNET SAUVIGNON - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE2003 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 90 PETIT VERDOT 10 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES CHARDONNAY - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 CHARDONNAY 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES DURIF- WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE DURIF - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 DURIF 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES MERLOT - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 MERLOT 85 PETIT VERDOT 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES RESERVE BOTRYTIS - WESTEND ESTATE 2003 SEMILLON 60 PEDRO XIMENEZ 40 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE GOLDEN MIST2003 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES BOTRYTIS SEMILLON - WESTEND ESTATE 2004 SEMILLON 85 PEDRO XIMENEZ 15 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE 2002 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE SHOW RESERVE 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BRIDGES SHIRAZ - WESTEND ESTATE LIMITED RELEASE RESERVE2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW 3 BROTHERS WINERY GISBORNE CHARDONNAY 2004 CHARDONNAY 100 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY WAIRARAPA PINOT NOIR 2004 PINOT NOIR 90 MALBEC 10 NZ 3 BROTHERS WINERY MARLBOROUGH SAUVIGNON BLANC 2005 SAUVIGNON BLANC 100 NZ ABERCORN A RESERVE' VINTAGE PORT 2004 CABERNET 100 A/NSW ABERCORN A RESERVE' SHIRAZ 2003 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN NJILLA 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/NSW ABERCORN GROWERS REVENGE 2002 SHIRAZ 40 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 40A/NSW ADINFERN ESTATE SHIRAZ 2004 SHIRAZ 100 A/WA ALCIRA VINEYARD NUGAN ESTATE 2002 CABERNET SAUVIGNON 100 A/SA ALLAN SCOTT WINES -

OUR WINES. ALL LOCAL Glasses, Carafes, Bottles. All Wines Are

OUR WINES. ALL LOCAL Glasses, Carafes, Bottles. SPARKLING RED 2019 Box Grove Vineyard Prosecco - $9 / 35 2012 Bald Rock Pinot Noir - $46 NV Tahbilk Couselant Chardonnay/Pinot Noir - $59 2018 Antcliffes Chase Pinot Noir - $15 / 45 / 60 NV Fowles Gingers Prince Sparkling Rose - $45 2018 Jo Nash Single Vineyard Pinot Noir - $72 NV The Bend Sparkling Shiraz - $35 2018 McPhersons The Angus Merlot - $36 2019 McPherson Wines ‘La Vue’ White Moscato - $9 / 27 / 34 2018 Tahbilk ‘GSM’ Grenache, Shiraz, Mourvèdre - $59 2017 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Shiraz - $9 / 27 / 34 WHITE 2017 Maygars Hill Shiraz - $60 2019 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Sauvignon Blanc - $9 / 27 / 34 2015 RPL Barrel Selection Shiraz - $72 2017 Kooyonga Creek Sauvignon Blanc - $39 2010 Hide and Seek Reserve Shiraz – $90 2019 Sibling Rivalry Sauvignon Blanc - $42 2010 Moon Shiraz - $92 2020 RPL No Picnic Pinot Gris - $42 2015 Fowles ‘The Rule Shiraz - $110 2020 Vino Relaxo Riesling - $44 2016 Anderson Fort Shiraz - $145 2019 Whistle & Hope Riesling - $48 2013 Tahbilk ‘1860’ Shiraz - $450 2019 Trust Riesling by Tar & Roses - $48 2016 Municipal Wines ‘Whitegate’ Tempranillo - $60 2019 Antcliffes Chase Riesling - $13 / 39 / 53 2018 Veldhuis Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot - $51 2020 Mac Forbes Spring Riesling - $65 2015 Elgo Cabernet Sauvignon $53 2018 Brave Goose Vineyard Viognier - $60 2017 Maygars Hill Cabernet Sauvignon - $60 2020 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Chardonnay - $34 2017 Sam Plunkett Cabernet Sauvignon - $73 2020 Stardust & Muscle Chardonnay - $11/ 33 / 43 2019 Seneca Cabernet Sauvignon -

Tasting Room Program Download

*Conditions apply, ask your store for more details. l’art de vivre by roche bobois Photo: Michel Gibert. Special thanks: Juan Antonio Sánchez Morales - www.adhocmsl.com - “Pieuvre” www.ekaacosta.com - TASCHEN. Manufactured in Europe. Beach Bay modular sofa, design Philippe Bouix Ovni cocktail tables, design Vincenzo Maiolino VANCOUVER CALGARY 716 West Hastings 225 10th Avenue SW Tel. 604-633-5005 Tel. 403-532-4401 [email protected] [email protected] Com plimentary 3D Interior Design Service* Showroom, collections, news and catalogs www.roche-bobois.com THE 37TH VANCOUVER INTERNATIONAL WINE FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 20 - MARCH 1, 2015 1,750+ wines * 170 wineries * 14 countries * 53 events * 8 days * 25,000 attendees Welcome to the 2015 Vancouver International Wine Festival, Canada’s premier wine show. This annual TABLE OF CONTENTS celebration of the grape has become a February highlight in Vancouver, with a full slate of wine tastings and WELCOME MESSAGES .................................................................................5 parties, lunches, brunches and dinners, seminars, and a three-day FESTIVAL PARTNERS.....................................................................................7 conference for trade professionals. The heart of VanWineFest, however, PARTICIPATING WINERIES ............................................................................8 is the International Festival Tastings, where all 170 wineries gather TASTING ROOM MAP...................................................................................9 -

Alternative and Extraordinary Australia

ALTERNATIVE AND EXTRAORDINARY AUSTRALIA MASTER CLASS AND FREE POUR TASTING WEDNESDAY, 17 APRIL 2019 BEDRIJVENCENTRUM DE PUNT, GENT Wine regions Welcome of Australia Darwin We’re delighted to be back in Belgium, following a successful event in Antwerp last year, sharing our wines and stories in Gent for the first time. Australia has thousands of wineries, dotted throughout 65 wine regions across the country. Our unique climate and vast landscape enables us to produce an incredibly diverse range of wine, which can be seen in more than 130 different INDIAN OCEAN grape varieties. NORTHERN TERRITORY At this master class, led by The Wine Detective, Sarah Ahmed, we’ll explore the country’s climatic diversity, winemaking brilliance and innovative spirit. QUEENSLAND Through these 12 wines, you’ll discover how Australian winemakers are experimenting with alternative varieties and new styles to create something WESTERN AUSTRALIA extraordinary. The line-up will showcase Mediterranean grape varieties and their unique style in Australia, as well as unusual and rare varieties. 28 South Eastern Australia* The master class is followed by a free pour tasting of Australia’s classic whites SOUTH AUSTRALIA Brisbane and summer reds. Taste fresh, elegant and iconic styles of Australian wine, 29 from Hunter Valley Semillon to Clare Valley Riesling, Mornington Peninsula 30 Pinot Noir to McLaren Vale Grenache. This is a great opportunity to revisit hero NEW SOUTH WALES styles as well as find out what’s coming out of Australia today. 1 31 2 Perth 10 32 33 3 GREAT 11 Exports of Australian wine continue to grow globally and there is positive 44 34 PACIFIC OCEAN AUSTRALIAN BIGHT 12 14 35 4 15 6 13 36 growth across a number of markets in Europe. -

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

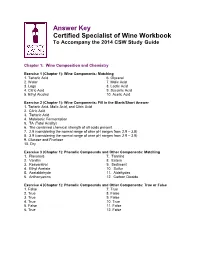

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Old World, New World, Third World? Reconceptualising the Worlds of Wine

Journal of Wine Research, 2010, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 57–75 Old World, New World, Third World? Reconceptualising the Worlds of Wine GLENN BANKS and JOHN OVERTON Original manuscript received, 08 April 2009 Revised manuscript received, 18 November 2009 ABSTRACT This paper argues that existing categories defining the geography of the world’s wine industry, principally the Old World/New World dichotomy, are flawed. Not only do they fail to represent adequately the complexity of production and marketing in those two broad regions but also, crucially, they do not acknowledge the significant and rapidly expanding production and consumption of wine in ‘Third World’ developing countries. Rather than argue for the addition of a ‘Third World’ category, we instead use the lens of recent work on globalisation to argue that such production requires us to re-examine the dichotomous Old/New distinction which structures much of the thinking around the global wine industry. It also requires us to more closely link changes in patterns of global wine consumption with developments in global production. Changing geographies of wine production have been driven, to a large extent, by the rapid expansion of both local wealthy elites and burgeoning middle classes in countries such as China and India. This has resulted in the development of local wineries, large and small, throughout the developing world. It has also seen new flows of investment both from established wine regions to these new sites of production and from companies and individuals in the developing world who have invested in established wine regions, whether in France or Australia. -

Current Wine List

Accessories - Wine BARFLY 24oz Mixing Glass 39.99 DeLaurenti Wine & Beer BARFLY Bar Spoon 19.99 Inventory BARFLY Boston Shaker Set 29.99 BARFLY Hawthorne Strainer 21.99 Last updated: BARFLY JapaneseStyleJigger 14.99 4/23/2021 BARFLY Wooden Muddler 16.99 DELAURENTI Wine Key 9.99 Inquire within re: RIEDEL Decanter 199.99 Special Orders TRUE Champagne Stopper 6.99 Out of State Shipping African Wine Quantity Discounts TESTALONGA Orange Skin 750ml 41.99 [email protected] TESTALONGA White Cortez 750ml 39.99 (206) 622-0141 ext. 3 TESTALONGA WishWasANinjaPetnat 27.99 Aperetif ATXA Vermouth Red 18.99 Submit requests from BORDIGA Vermouth Bianco 42.99 this list in the comments BRAVO Vermut del Sol 750ml 24.99 field at check out BYRRH Grand Quinquina 19.99 CAPERITIF 750ml 31.99 CAPPELLETTI Aperitivo 19.99 CARDAMARO Vino Amaro 24.99 CARPANO Antica Formula 1ltr 39.99 CINZANO Extra Dry Vermouth 10.99 CINZANO Rosso Vermouth 13.99 COCCHI Americano Rossa 21.99 COCCHI Americano Rossa 375ml 13.99 COCCHI Vermouth di Torino 375 13.99 CONTRATTO Americano 24.99 CONTRATTO Rosso Vermouth 24.99 DOLIN Vermouth Blanc 15.99 DOLIN Vermouth Dry 15.99 DOLIN Vermouth Rouge 15.99 FRED JERBIS Vermouth 750ml 44.99 LILLET Red 26.99 LILLET Rose 26.99 LILLET White 26.99 MANCINO Vermouth Chinato 500ml 41.99 MANCINO Vermouth Rosso 38.99 MANCINO Vermouth Rosso Vecchio 189.99 MANCINO Vermouth Sakura 500ml 48.99 MANCINO Vermouth Secco 38.99 MATTEI Corse Cap Blanc 21.99 MATTEI Corse Cap Rouge 21.99 REGAL ROGUE Bold Red 29.99 REGAL ROGUE Daring Dry 24.99 REGAL ROGUE Lively White -

When Malbec Became Argentine: an Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza Dominique Lee

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2018 When Malbec became Argentine: An Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza Dominique Lee Recommended Citation Lee, Dominique, "When Malbec became Argentine: An Analysis of the Quality Wine Revolution in Mendoza" (2018). Scripps Senior Theses. 1224. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1224 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN MALBEC BECAME ARGENTINE: AN ANALYSIS OF THE QUALITY WINE REVOLUTION IN MENDOZA by DOMINIQUE LEE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR GABRIELA MORALES, SCRIPPS COLLEGE PROFESSOR BRIAN KEELEY, PITZER COLLEGE APRIL 12th, 2018 Lee 2 Table Contents Abstract 4 1.0 Why Study Wine? 5 1.0.1 Quality Versus Quantity 7 1.1 Methodology 9 1.2 An Introduction to Terroir 11 2. History of Winemaking in Argentina 14 2.1 Government Regulation: A Precursor to Change 15 2.1.1 Argentina’s Turbulent Economy 16 2.2 Was there a Revolution in Argentinian Wine Production? 17 2.2.1 Thomas Kuhn’s Paradigm Shifts 18 2.3 Paradigm Shift in Mendoza Wine Production 22 2.3.1 The Previous Paradigm: Prior to the 1990s 23 2.3.2 The Paradigm Shift 26 2.3.3 The New Paradigm 28 2.4 Conversion Between Paradigms 30 2.5 What is Progress within Paradigms? 31 2.6 Beginning of Geographic Indication Systems 34 3. -

Regal Riesling Extends Its Reign

Regal riesling extends its reign 274_Part_A_Front.indd 34 9/12/2015 9:11:05 AM DAN TRAUCKI UNTIL fairly recently riesling was synonymous with being lots of talk of a “chardonnay revival”, in vintage has been growing not only in size but also in German wine. It is the noble grape variety that for 2015, riesling prices in South Australia exceeded the relevance to the riesling world. As chairman, Helm hundreds of years made the best of, as well as most prices of chardonnay in every region in which both says: “This is not just another wine show, it is an event of, Germany’s white wine. These wines were mainly varieties are grown. to promote riesling from the vineyard through to the low in alcohol, around 8-11 per cent and in most The second part of the riesling story starts in 2000, consumer. Imparting knowledge about riesling is cases anywhere from slightly sweet through to the when respected Canberra winemaker, Ken Helm AM, the essence of the event. Our aim is to be the world amazingly sweet trockenbeerenauslese style. Only created the Canberra Riesling Challenge in order to centre for communicating riesling knowledge”. In a small proportion was dry (kabinet) in style. benchmark and promote rieslings from across the keeping with this theme, the organisers announced The winds of change started as a zephyr in 1953, nation. The aim being to improve the quality and that from 2015 onwards, one of the masterclasses when under the inspired leadership of Colin Gramp appreciation of Australian riesling. In the same year conducted as part of the CIRC would feature a AM, Orlando Wines made the first modern white wine Clare Valley winemakers unanimously adopted the riesling growing region of the world. -

The Goulburn Explorer

What better way to experience the beauty of the Goulburn River than by cruising along its waters in style. The Goulburn Explorer River Cruiser links Mitchelton and Tahbilk, two of Victoria’s best-loved wineries, and the charming township of Nagambie, providing a memorable experience for food and wine lovers. Available for private events, corporate parties and twilight cruises, this 12m vessel seats up to 49 passengers with two open-plan decks, bathroom and audio-visual equipment. Murray River Strathmerton Cobram Situated at the gateway to the Goulburn Valley approximately 90 minutes Nathalia Monichino WINERY from Melbourne’s CBD, The Goulburn Explorer River Cruiser is one of Yarrawonga Echuca Numurkah CRUISES regional Victoria’s must see and do experiences. Goulburn River Tungamah Tongala Kyabram THE GOULBURN VALLEY Dookie Merrigum Shepparton Girgarre Mooroopna WINE REGION Tallis Tatura ITINERARY Stanhope Toolamba Departs from Nagambie Lakes Leisure Park @ 10:30am Murray River Colbinabbin Rushworth Arrives at Tahbilk Winery @ 11:30am Strathmerton Cobram Murchison Departs from Tahbilk Winery @ 12:00pm Longleat Violet Town Arrives at Mitchelton @ 12:30pm Nathalia Monichino Goulburn Valley HWY NYarrawonga Echuca Numurkah Departs Mitchelton @ 2:30pm Nagambie Goulburn Terrace Goulburn River Euroa David Traeger Disembarks at Nagambie Lakes Leisure Park @ 4:00pm Tahbilk Tungamah Tongala Mitchelton Hume FWY Kyabram Avenel Fowles Dookie Merrigum Shepparton Girgarre Mooroopna PRICE Tallis Tatura Stanhope Seymour Toolamba Adult $40pp Rocky Passes -

New World Wine Awards 2020 Medal Results WINES ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY by MEDAL

New World Wine Awards 2020 Medal Results WINES ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY MEDAL Medal Wine Name & Vintage Medal Wine Name & Vintage Gold Allan Scott Marlborough Pinot Gris 2020 Gold Morton Estate Brut Gold Alpha Domus Collection Sauvignon Blanc 2019 Gold Mount Brown Estates Pinot Noir 2019 Gold Angove Organic Shiraz Cabernet 2019 Gold Mount Riley "The Bonnie" Pinot Rosé 2020 Gold Banrock Station Pink Moscato 2019 Gold Mount Riley Limited Release Sauvignon Blanc 2020 Gold Barking Mad Shiraz 2018 Gold Mount Riley Marlborough Riesling 2020 Gold Black Cottage Sauvignon Blanc 2020 Gold Nga Waka Three Paddles Martinborough Pinot Noir 2017 Gold Borthwick Paper Road Pinot Noir 2019 Gold Paritua Stone Paddock Syrah 2018 Gold Brancott Estate Hawkes Bay Merlot 2019 Gold Penfolds Koonunga Hill Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 Gold Church Road Hawkes Bay Chardonnay 2019 Gold Pepperjack Shiraz 2017 Gold Church Road Gold Providore Pinot Noir First Edition 2019 Hawkes Bay Merlot Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 Gold Rapaura Springs Classic Sauvignon Blanc 2020 Gold Cinzano Prosecco D.O.C Gold Roaring Meg Pinot Gris 2019 Gold Clearview Estate Beachhead Chardonnay 2019 Gold Rocky Point Pinot Gris 2020 Gold Coopers Creek Gold Rojo Garnacha 2019 Select Vineyards 'Bell-Ringer' Albariño 2019 Gold De Bortoli Woodfired Cabernet Sauvignon 2019 Gold Running With Bulls Tempranillo 2019 Gold Earthworks Succession Shiraz Cabernet Sauvignon 2019 Gold Saint Clair James Sinclair Pinot Noir 2019 Gold Farnese Fantini Sangiovese 2019 Gold Seifried Nelson Gewürztraminer 2020 Gold Framingham