Great Expectations.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Her Own Hand: Female Agency Through Self-Castration in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 11-20-2008 By her Own Hand: Female Agency through Self-Castration in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction Angela Marie Hall-Godsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hall-Godsey, Angela Marie, "By her Own Hand: Female Agency through Self-Castration in Nineteenth- Century British Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BY HER OWN HAND: FEMALE AGENCY THROUGH SELF-CASTRATION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION by ANGELA MARIE HALL-GODSEY Under the Direction of Dr. Michael Galchinsky ABSTRACT By Her Own Hand: Female Agency Through Self-Castration in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction explores the intentional methods of self-castration that lead to authorial empowerment. The project relies on the following self-castration formula: the author’s recognition of herself as a being defined by lack. This lack refers to the inability to signify within the phallocentric system of language. In addition to this initial recognition, the female author realizes writing for public consumption emulates the process of castration but, nevertheless, initiates the writing process as a way to resituate the origin of castration—placing it in her own hand. The female writer also recognizes her production as feminine and, therefore works to castrate her own femininity in her pursuit to create texts that are liberated from the critical assignation of “feminine productions.” Female self-castration is a violent act of displacement. -

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

A Biographical Note on Charles Dickens *** Uma Nota Biográfica Sobre Charles Dickens

REVISTA ATHENA ISSN: 2237-9304 Vol. 14, nº 1 (2018) A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON CHARLES DICKENS *** UMA NOTA BIOGRÁFICA SOBRE CHARLES DICKENS Sophia Celina Diesel1 Recebimento do texto: 25 de abril de 2018 Data de aceite: 27 de maio de 2018 RESUMO: As biografias de autores famosos costumam trazer supostas explicações para a sua obra literária. Foi o caso com Charles Dickens e a revelação do episódio da fábrica de graxa quando ele era menino, inspiração para David Copperfield. Exposta na biografia póstuma escrita pelo amigo próximo de Dickens John Forster, o episódio rapidamente tornou-se parte do imaginário Dickensiano. Porém é interessante observar mais de perto tais explicações e considerar outros pontos de vista, incluindo o do próprio autor. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Fábrica de Graxa; Literatura Vitoriana; Biografia literária. ABSTRACT: The biographies of famous authors often bring supposed explanations for their literary work, especially for complicated or obscure passages. Such was the case with Charles Dickens and the revelation of the blacking factory episode when he was a boy, which served later as inspiration for his novel David Copperfield. Exposed in the posthumous biography written by Dickens’s close friend John Forster it quickly called fan’s attention and became part of the Dickensian imaginary. Yet, it is interesting to look closer at such easy explanations and consider different views, including the author’s himself. KEYWORDS: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Blacking factory; Victorian literature; Literary biography. 1 Mestre pela Loughborough University, no Reino Unido, em Literatura Inglesa. Doutoranda em Estudos em Literatura na UFRGS - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. -

Great Expectations By

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 1860 -1861 TheBestNotes Study Guide by TheBestNotes.com Staff Reprinted with permission from TheBestNotes.com Copyright © 2003, All Rights Reserved Distribution without the written consent of TheBestNotes.com is strictly prohibited. LITERARY ELEMENTS SETTING The action of Great Expectations takes place in a limited geography between a small village at the edge of the North Kent marshes, a market town in which Satis House is located, and the greater city of London. The protagonist, Pip, grows up in the marsh village. Eventually he becomes a frequent visitor to Satis House, located in the market town. Upon inheriting a good deal of money, he moves to London, where he is taught to be a gentleman. Throughout the novel, Pip travels between these three locations in pursuit of his great expectations. LIST OF CHARACTERS Major Characters Pip - Philip Pirip He is the narrator and hero of the novel. He is a sensitive orphan raised by his sister and brother-in-law in rural Kent. After showing kindness to an escaped convict, he becomes the beneficiary of a great estate. He rejects his common upbringing in favor of a more refined life in London, unaware that his benefactor is actually the convict. By the end of the novel he learns a great lesson about friendship and loyalty, and gives up his “great expectations” in order to be more true to his past. Joe Gargery A simple and honest blacksmith, and the long-suffering husband of Mrs. Joe. He is Pip’s brother-in-law, as well as a loyal friend and ally. -

Magwitch's Revenge on Society in Great Expectations

Magwitch’s Revenge on Society in Great Expectations Kyoko Yamamoto Introduction By the light of torches, we saw the black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud of the shore, like a wicked Noah’s ark. Cribbed and barred and moored by massive rusty chains, the prison-ship seemed in my young eyes to be ironed like the prisoners (Chapter 5, p.34). The sight of the Hulk is one of the most impressive scenes in Great Expectations. Magwitch, a convict, who was destined to meet Pip at the churchyard, was dragged back by a surgeon and solders to the hulk floating on the Thames. Pip and Joe kept a close watch on it. Magwitch spent some days in his hulk and then was sent to New South Wales as a convict sentenced to life transportation. He decided to work hard and make Pip a gentleman in return for the kindness offered to him by this little boy. He devoted himself to hard work at New South Wales, and eventually made a fortune. Magwitch’s life is full of enigma. We do not know much about how he went through the hardships in the hulk and at NSW. What were his difficulties to make money? And again, could it be possible that a convict transported for life to Australia might succeed in life and come back to his homeland? To make the matter more complicated, he, with his money, wants to make Pip a gentleman, a mere apprentice to a blacksmith, partly as a kind of revenge on society which has continuously looked down upon a wretched convict. -

2017 Educational Performances

2017 EDUCATIONAL PERFORMANCES A Production of the Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire Holidays at Mount Hope is a different kind of interactive experience. Through the doors of Mount Hope Mansion, you’ll enter a Christmas party, time to meet and mingle with a host of characters and a variety of Holiday decorations. Sing along, share games and traditions, and rejoice in the spirit of the season with holiday characters. 2017 Stories & Cast— Christmas, 1899: Fredrick Schwartz Jr., Son of the founder of the FAO Schwartz Toy Bazaar is throwing a Christmas party fit for the end of a century. Filling the Grubb Estate in Mount Hope, Pennsylvania to the brim with the best examples of the toys and games that make children look forward to Christmas morning, Schwartz has transformed the mansion into a Santa’s Workshop that can warm even the coldest heart. He’s invited some of his closest friends over, including the game-loving Parker Brothers (and their sister, Dot), and they have put together a Christmas pageant for all of the guests. Fun, games, and heart-warming performances will fill this Christmas with the love, joy, and generosity of the season. A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens The story of a bitter old miser named Ebenezer Scrooge, his transformation into a gentler, kindlier man brought on by visitations by the Ghosts of Christmases Past, Present and Yet to Come. Presented with warmth, humor, tradition and a bit of audience support, the enduring tale of A Christmas Carol springs from storybook to the stage. A Visit from St. Nicholas, by Clemet Clarke Moore Written as a Christmas gift for his six children, “A Visit from St. -

The Treatment of Children in the Novels of Charles

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN IN THE NOVELS OF CHARLES DICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY CLEOPATRA JONES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1948 ? C? TABLE OF CONTENTS % Pag® PREFACE ii CHAPTER I. REASONS FOR DICKENS' INTEREST IN CHILDREN ....... 1 II. TYPES OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 10 III. THE FUNCTION OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 20 IV. DICKENS' ART IN HIS TREATMENT OF CHILDREN 33 SUMMARY 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PREFACE The status of children in society has not always been high. With the exception of a few English novels, notably those of Fielding, child¬ ren did not play a major role in fiction until Dickens' time. Until the emergence of the Industrial Revolution an unusual emphasis had not been placed on the status of children, and the emphasis that followed was largely a result of the insecure and often lamentable position of child¬ ren in the new machine age. Since Dickens wrote his novels during this period of the nineteenth century and was a pioneer in the employment of children in fiction, these facts alone make a study of his treatment of children an important one. While a great deal has been written on the life and works of Charles Dickens, as far as the writer knows, no intensive study has been made of the treatment of children in his novels. All attempts have been limited to chapters, or more accurately, to generalized statements in relation to his life and works. -

Norms Governing the Dialect Translation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations: an English-Greek Perspective

International Linguistics Research; Vol. 1, No. 1; 2018 ISSN 2576-2974 E-ISSN 2576-2982 https://doi.org/10.30560/ilr.v1n1p49 Norms Governing the Dialect Translation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations: An English-Greek Perspective Despoina Panou1 1 Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting, Ionian University, Greece Correspondence: Despoina Panou, Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting, Ionian University, Greece. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 11, 2018; Accepted: March 28, 2018; Published: April 16, 2018 Abstract This paper aims to investigate the norms governing the translation of fiction from English into Greek by critically examining two Greek translations of Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations. One is by Pavlina Pampoudi (Patakis, 2016) and the other, is by Thanasis Zavalos (Minoas, 2017). Particular attention is paid to dialect translation and special emphasis is placed on the language used by one of the novel’s prominent characters, namely, Abel Magwitch. In particular, twenty instances of Abel Magwitch’s dialect are chosen in an effort to provide an in-depth analysis of the dialect-translation strategies employed as well as possible reasons governing such choices. It is argued that both translators favour standardisation in their target texts, thus eliminating any language variants present in the source text. The conclusion argues that societal factors as well as the commissioning policies of publishing houses influence to a great extent the translators’ behaviour, and consequently, the dialect-translation strategies adopted. Hence, greater emphasis on the extra-linguistic, sociological context is necessary for a thorough consideration of the complexities of English-Greek dialect translation of fiction. -

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79 Paul Ellis University College London Doctor of Philosophy UMI Number: U602586 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602586 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis argues that real-life forgery cases significantly shaped the form of Victorian fiction. Forgeries of bills of exchange, wills, parish registers or other documents were depicted in at least one hundred novels between 1846 and 1879. Many of these portrayals were inspired by celebrated real-life forgery cases. Forgeries are fictions, and Victorian fiction’s representations of forgery were often self- reflexive. Chapter one establishes the historical, legal and literary contexts for forgery in the Victorian period. Chapter two demonstrates how real-life forgers prompted Victorian fiction to explore its ambivalences about various conceptions of realist representation. Chapter three shows how real-life forgers enabled Victorian fiction to develop the genre of sensationalism. Chapter four investigates how real-life forgers influenced fiction’s questioning of its epistemological status in Victorian culture. -

Charles Dickens As Criminologist Paul Chatham Squires

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 29 Article 2 Issue 2 July-August Summer 1938 Charles Dickens as Criminologist Paul Chatham Squires Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Paul Chatham Squires, Charles Dickens as Criminologist, 29 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 170 (1938-1939) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CHARLES DICKENS AS CRIMINOLOGIST PAUL CHATHAM SQUIRES, PH.D.* "Dickens had a singularly just mind. He was wild in his caricatures, but very sane in his impressions."--G. K. Chesterton. Lawyers, and learned professors of law, have investigated the contributions made by Dickens to the history of the common law and chancery. Holdsworth states: "In these lectures I intend to show you that the treatment by Dickens of various aspects of the law and the lawyers of his day, is a very valuable addition to our authorities, not only for that period, but also for earlier periods in our legal history."'- He concludes his critical examination by saying that the information left us by Dickens justifies "my con- tention that the extent, the variety, and the accuracy of this . entitles us to reckon one of the greatest of our English novelists as a member of the select band of our legal historians."'2 But, strange to remark, no one has seemed to think it worth while or deserving of the great effort involved, systematically to ascertain Dicken's precise position on the nature of the criminal and the eternal questions of criminology. -

Answer Sheet

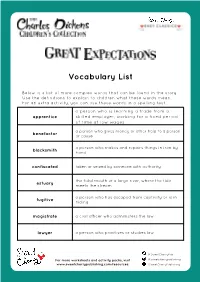

Vocabulary List Below is a list of more complex words that can be found in the story. Use the definitions to explain to children what these words mean. For an extra activity, you can use these words in a spelling test. a person who is learning a trade from a apprentice skilled employer, working for a fixed period of time at low wages a person who gives money or other help to a person benefactor or cause a person who makes and repairs things in iron by blacksmith hand confiscated taken or seized by someone with authority the tidal mouth of a large river, where the tide estuary meets the stream a person who has escaped from captivity or is in fugitive hiding magistrate a civil officer who administers the law lawyer a person who practises or studies law @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Plot Sequencing Answer Sheet 1. Pip lives with his sister and her husband, Joe. One day, a big grey man approaches Pip when he visits his parents’ graves. The man asks Pip to bring him food and a file to cut off the cuffs on his ankles. 2. Pip agrees and later finds out that the man is an escaped convict from a nearby prison ship. The police find the man and Pip makes sure he knows that he never told on him. 3. Pip meets Miss Havisham and Estella at Sati’s House. Although Estella is cold towards him, he visits regularly for a few years before his apprenticeship starts and Estella leaves for London. -

Furies of the Guillotine: Female Revolutionaries In

FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Tori Anne Horton FALL 2016 © 2016 Tori Anne Horton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION A Thesis by Tori Anne Horton Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Mona Siegel __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Rebecca Kluchin ____________________________ Date iii Student: Tori Anne Horton I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Dr. Jeffrey Wilson Date Department of History iv Abstract of FURIES OF THE GUILLOTINE: FEMALE REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND IN VICTORIAN LITERARY IMAGINATION by Tori Anne Horton The idea of female revolutionaries struck a particular chord of terror both during and after the French Revolution, as represented in both legislation and popular literary imagination. The level and form of female participation in the events of the Revolution varied among social classes. Female participation during the Revolution led to an overwhelming fear of women demanding and practicing democratic rights in both a nonviolent manner (petitioning for education, demanding voting rights, serving on committees), and in a violent manner (engaging in armed protest and violent striking). The terror surrounding female democratic participation was manifested in the fear of the female citizen, or citoyenne.