Attitudes De Se and Logophoricity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions Under Discussion: from Sentence to Discourse∗

Questions under Discussion: From sentence to discourse∗ Anton Benz Katja Jasinskaja July 14, 2016 Abstract Questions under discussion (QUD) is an analytic tool that has recently become more and more popular among linguists and language philosophers as a way to characterize how a sentence fits in its context. The idea is that each sentence in discourse addresses a (of- ten implicit) QUD either by answering it, or by bringing up another question that can help answering that QUD. The linguistic form and the interpretation of a sentence, in turn, may depend on the QUD it addresses. The first proponents of the QUD approach (von Stut- terheim & Klein, 1989; van Kuppevelt, 1995) thought of it as a general approach to the analysis of discourse structure where structural relations between sentences in a coherent discourse are understood in terms of relations between questions they address. However, the idea did not find broad application in discourse structure analysis, where theories aiming at logical discourse representations are predominantly based on the notion of coherence re- lations (Mann & Thompson, 1988; Hobbs, 1985; Asher & Lascarides, 2003). The problem of finding overt markers for QUDs means that they are also difficult to utilize for quanti- tative measures of discourse coherence (McNamara et al., 2010). At the same time QUD proved useful in the analysis of a wide range of linguistic phenomena including accentua- tion, discourse particles, presuppositions and implicatures. The goal of this special issue is to bring together cutting-edge research that demonstrates the success of QUD in linguistics and the need for the development of a comprehensive model of discourse coherence that incorporates the notion of QUD as its integral part. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Predicate Logic

Logical Form & Predicate Logic Jean Mark Gawron Linguistics San Diego State University [email protected] http://www.rohan.sdsu.edu/∼gawron Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 1/30 Predicates and Arguments Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 2/30 Logical Form The Logical Form of English sentences can be represented by formulae of Predicate Logic, What do we mean by the logical form of a sentence? We mean: we can capture the truth conditions of complex English expressions in predicate logic, given some account of the denotations (extensions) of the simple expressions (words). Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 3/30 The Leading Idea: Extensions Nouns, verbs, and adjectives have predicates as their translations. What does ’predicate’ mean? ’Predicate’ means what it means in predicate logic. Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 4/30 Intransitive verbs Translating into predicate logic (1) a. Johnwalks. b. walk(j) (2) a. [[j]] = John b. “The extension of ’j’ is the individual John.” c. [[walk]] = {x | x walks } d. “The extension of ’walk’ is the set of walkers” (3) a. [[John walks]] = [[walk(j)]] b. [[walk(j)]] = true iff [[j]] ∈ [[walk]] Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 5/30 Extensional denotations • Remember two kinds of denotation. For work with logic, denotations are always extensions. • We call a denotation such as [[walk]] (a set) an extension, because it is defined by the set of things the word walk describes or “extends over” • The denotation [[j]] is also extensional because it is defined by the individual the word John describes. • Next we extend extensional denotation to transitive verbs, nouns, and sentences. -

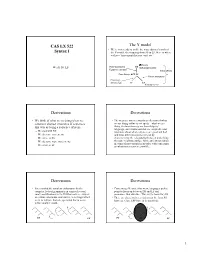

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: a Case for Short Binding

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: A Case for Short Binding Rodolfo Delmonte Ca' Garzoni-Moro, San Marco 3417, Università "Ca Foscari", 30124 - VENEZIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Relative clause attachment may be triggered by binding requirements imposed by a short anaphor contained within the relative clause itself: in case more than one possible attachment site is available in the previous structure, and the relative clause itself is extraposed, a conflict may arise as to the appropriate s/c-structure which is licenced by grammatical constraints but fails when the binding module tries to satisfy the short anaphora local search for a bindee. 1 Introduction It is usually the case that anaphoric and pronominal binding take place after the structure building phase has been successfully completed. In this sense, c-structure and f-structure in the LFG framework - or s-structure in the chomskian one - are a prerequisite for the carrying out of binding processes. In addition, they only interact in a feeding relation since binding would not be possibly activated without a complete structure to search, and there is no possible reversal of interaction, from Binding back into s/c-structure level seen that they belong to two separate Modules of the Grammar. As such they contribute to each separate level of representation with separate rules, principles and constraints which need to be satisfied within each Module in order for the structure to be licensed for the following one. However we show that anaphoric binding requirements may cause the parser to fail because the structure is inadequate. We propose a solution to this conflict by anticipating, for anaphors only the though, the agreement matching operations between binder and bindee and leaving the coindexation to the following module. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Context Pragmatics Definition of Pragmatics

Pragmatics • to ask a question: Maybe Sandy’s reassuring you that Kim’ll get home okay, even though she’s walking home late at night. Sandy: She’s got more than lipstick and Kleenex in that purse of hers. • What is Pragmatics? You: Kim’s got a knife? • Context and Why It’s Important • Speech Acts – Direct Speech Acts – Indirect Speech Acts • How To Make Sense of Conversations – Cooperative Principle – Conversational Maxims Linguistics 201, Detmar Meurers Handout 3 (April 9, 2004) 1 3 Definition of Pragmatics Context Pragmatics is the study of how language is used and how language is integrated in context. What exactly are the factors which are relevant for an account of how people use language? What is linguistic context? Why must we consider context? We distinguish several types of contextual information: (1) Kim’s got a knife 1. Physical context – this encompasses what is physically present around the speakers/hearers at the time of communication. What objects are visible, where Sentence (1) can be used to accomplish different things in different contexts: the communication is taking place, what is going on around, etc. • to make an assertion: You’re sitting on a beach, thinking about how to open a coconut, when someone (2) a. Iwantthat book. observes “Kim’s got a knife”. (accompanied by pointing) b. Be here at 9:00 tonight. • to give a warning: (place/time reference) Kim’s trying to bully you and Sandy into giving her your lunch money, and Sandy just turns around and starts to walk away. She doesn’t see Kim bring out the butcher knife, and hears you yell behind her, “Kim’s got a knife!” 2 4 2. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb.