Implicit Memory: History and Current Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unconscious Mind: Kinder and Gentler Than That

3/20/2013 The Freudian 20th Century “Freud in 21st-Century America” The Unconscious Mind: Kinder and Gentler Than That John F. Kihlstrom Forbidden Planet (1956) Department of Psychology University of California, Berkeley 1 2 The Discovery of the Unconscious Petites Perceptions Ellenberger (1970) Leibniz (1704/1981); Ellenberger (1970) • At every moment there is in us an infinity of perceptions, unaccompanied by awareness or reflection…. That is why we are never indifferent, even when we appear to be most so…. The choice that we make arises from these insensible stimuli, which… make us find one direction of movement more comfortable than the 3 other. 4 The Limen Unconscious Inferences Herbart (1819) Helmholtz (1866/1968) • One of the older ideas can… be • The psychic activities that lead us to infer that completely driven out of consciousness by there in front of us at a certain place there is a a new much weaker idea. On the other certain object of a certain character, are generally hand its pressure there is not to be not conscious activities, but unconscious ones. In regarded as without effect; rather it works their result they are the equivalent to conclusion…. with full power against the ideas which are But what seems to differentiate them from a conclusion, in the ordinary sense of that word, is present in consciousness. It thus causes that a conclusion is an act of conscious thought…. a particular state of consciousness, though Still it may be permissible to speak of the psychic its object is in no sense really imagined. acts of ordinary perception as unconscious 5 conclusions…. -

Implicit and Explicit Knowledge About Language

Comp. by: TPrasath Date:27/12/06 Time:22:59:29 Stage:First Proof File Path:// spiina1001z/womat/production/PRODENV/0000000005/0000001817/0000000016/ 0000233189.3D Proof by: QC by: NICK ELLIS IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT KNOWLEDGE ABOUT LANGUAGE INTRODUCTION Children acquire their first language (L1) by engaging with their caretakers in natural meaningful communication. From this “evidence” they automatically acquire complex knowledge of the structure of their language. Yet paradoxically they cannot describe this knowledge, the discovery of which forms the object of the disciplines of theoretical lin- guistics, psycholinguistics, and child language acquisition. This is a difference between explicit and implicit knowledge—ask a young child how to form a plural and she says she does not know; ask her “here is a wug, here is another wug, what have you got?” and she is able to reply, “two wugs.” The acquisition of L1 grammar is implicit and is extracted from experience of usage rather than from explicit rules—simple expo- sure o normal linguistic input suffices and no explicit instruction is needed. Adult acquisition of second language (L2) is a different matter in that what can be acquired implicitly from communicative contexts is typically quite limited in comparison to native speaker norms, and adult attainment of L2 accuracy usually requires additional resources of explicit learning. The various roles of consciousness in second language acquisi- tion (SLA) include: the learner noticing negative evidence; their attending to language form, their perception focused by social scaffolding or explicit instruction; their voluntary use of pedagogical grammatical descriptions and analogical reasoning; their reflective induction of metalinguistic insights about language; and their consciously guided practice which results, eventually, in unconscious, automatized skill. -

Implicit and Explicit Learning of Languages Patrick Rebuschat

Introduction: Implicit and explicit learning of languages Patrick Rebuschat (Lancaster University) Introduction to the forthcoming volume: Rebuschat, P. (Ed.) (in press, 2015). Implicit and explicit learning of languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Implicit learning, essentially the process of acquiring unconscious (implicit) knowledge, is a fundamental feature of human cognition (Cleeremans, Destrebecqz, & Boyer, 1998; Dienes, 2012; Perruchet, 2008; Shanks, 2005; Reber, 1993). Many complex behaviors, including language comprehension and production (Berry & Dienes, 1993; Winter & Reber, 1994), music cognition (Rohrmeier & Rebuschat, 2012), intuitive decision making (Plessner, Betsch, & Betsch, 2008), and social interaction (Lewicki, 1986), are thought to be largely dependent on implicit knowledge. The term implicit learning was first used by Arthur Reber (1967) to describe a process during which subjects acquire knowledge about a complex, rule-governed stimulus environment without intending to and without becoming aware of the knowledge they have acquired. In contrast, the term explicit learning refers to a process during which participants acquire conscious (explicit) knowledge; this is generally associated with intentional learning conditions, e.g., when participants are instructed to look for rules or patterns. In his seminal study, Reber (1967) exposed subjects to letter sequences (e.g., TPTS, VXXVPS and TPTXXVS) by means of a memorization task. In experiment 1, subjects were presented with letter sequences and simply asked to commit them to memory. One group of subjects was given sequences that were generated by means of a finite-state grammar (Chomsky, 1956, 1957; Chomsky & Miller, 1958), while the other group received randomly 1 constructed sequences. The results showed that grammatical letter sequences were learned more rapidly than random letter sequences. -

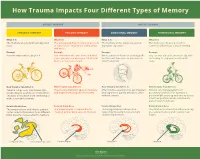

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Evidence of Automatic Processing in Sequence Learning Using Process-Dissociation

RESEARCH ARTICLE ADVANCES IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Evidence of automatic processing in sequence learning using process-dissociation Heather M. Mong, David P. McCabe, and Benjamin A. Clegg Department of Psychology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA ABSTRACT This paper proposes a way to apply process-dissociation to sequence learning in addition and ex- tension to the approach used by Destrebecqz and Cleeremans (2001). Participants were trained on two sequences separated from each other by a short break. Following training, participants self-reported their knowledge of the sequences. A recognition test was then performed which re- quired discrimination of two trained sequences, either under the instructions to call any sequence encountered in the experiment “old” (the inclusion condition), or only sequence fragments from one half of the experiment “old” (the exclusion condition). The recognition test elicited automatic KEYWORDS and controlled process estimates using the process dissociation procedure, and suggested both implicit learning, sequence processes were involved. Examining the underlying processes supporting performance may pro- learning, process- vide more information on the fundamental aspects of the implicit and explicit constructs than has dissociation, consciousness been attainable through awareness testing. INTRODUCTION Shanks, 2005), and numerous definitions of the term itself have been offered (Dienes & Perner, 1999; Frensch, 1998). This variety is further The serial reaction time task (SRTT) has become an extremely pro- reflected in an array of methods for assessing the presence or absence ductive method for studying sequence learning (for reviews, see of explicit knowledge. Issues raised have included whether explicit Abrahamse, Jimenez, Verwey, & Clegg, 2010; Clegg, DiGirolamo, knowledge is necessary for learning, what awareness tests should be & Keele, 1998). -

1 Personality and Cognitions Underlying Entrepreneurial Intentions Benjamin R. Walker a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment O

1 Personality and Cognitions underlying Entrepreneurial Intentions Benjamin R. Walker A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Management UNSW Business School March 30, 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Originality statement .................................................................................................................. 7 Publications and conference presentations arising from this thesis ........................................... 8 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 9 Thesis Abstract......................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2: Assessing the impact of revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory ...................... 20 Table 1: Articles with original Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (o-RST) and revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) measures .......................................................... 26 Table 2: Categorization of original Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (o-RST) and revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST) studies in the five years from 2010-2014 ........ 29 Chapter 3: How -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

Implicit Learning and Tacit Knowledge

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General Copyrighl 1989 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1989, Vol. 118, No. 3, 219-235 0096-3445/89/500,75 Implicit Learning and Tacit Knowledge Arthur S. Reber Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center City University of New York I examine the phenomenon of implicit learning, the process by which knowledge about the rale- governed complexities of the stimulus environment is acquired independently of conscious attempts to do so. Our research with the two, seemingly disparate experimental paradigms of synthetic grammar learning and probability learning is reviewed and integrated with other approaches to the general problem of unconscious cognition. The conclusions reached are as follows: (a) Implicit learning produces a tacit knowledge base that is abstract and representative of the structure of the environment; (b) such knowledge is optimally acquired independently of conscious efforts to learn; and (c) it can be used implicitly to solve problems and make accurate decisions about novel stimulus circumstances. Various epistemological issues and related prob- 1 lems such as intuition, neuroclinical disorders of learning and memory, and the relationship of evolutionary processes to cognitive science are also discussed. Some two decades ago the term implicit learning was first lined, and analyzed, but virtually no attention was paid to the used to characterize how one develops intuitive knowledge processes by which these implicit memories "got there." This about the underlying structure of a complex stimulus envi- general lack of attention to the acquisition problem may be ronment (Reber, 1965, 1967). In those early writings, I argued one of the reasons why much recent theorizing has been that implicit learning is characterized by two critical features: oriented toward a nativist position (e.g., Chomsky, 1980; (a) It is an unconscious process and (b) it yields abstract Fodor, 1975, 1983; Gleitman & Wanner, 1982). -

An Examination of Introductory Psychology Textbooks in America Randall D

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 1992 Portraits of a Discipline: An Examination of Introductory Psychology Textbooks in America Randall D. Wight Ouachita Baptist University, [email protected] Wayne Weiten Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Weiten, W. & Wight, R. D. (1992). Portraits of a discipline: An examination of introductory psychology textbooks in America. In C. L. Brewer, A. Puente, & J. R. Matthews (Eds.), Teaching of psychology in America: A history (pp. 453-504). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 20 PORTRAITS OF A DISCIPLINE: AN EXAMINATION OF INTRODUCTORY PSYCHOLOGY TEXTBOOKS IN AMERICA WAYNE WEITEN AND RANDALL D. WIGHT The time has gone by when any one person could hope to write an adequate textbook of psychology. The science has now so many branches, so many methods, so many fields of application, and such an immense mass of data of observation is now on record, that no one person can hope to have the necessary familiarity with the whole. -An author of an introductory psychology text If we compare general psychology textbooks of today with those of from ten to twenty years ago we note an undeniable trend toward amelio- We are indebted to several people who provided helpful information in responding to our survey discussed in the second half of the chapter, including Solomon Diamond for calling attention to Samuel Johnson and Noah Porter, Ernest R. -

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W. D. Stevens, G. S. Wig, and D. L. Schacter, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ª 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 2.33.1 Introduction 623 2.33.2 Influences of Explicit Versus Implicit Memory 624 2.33.3 Top-Down Attentional Effects on Priming 626 2.33.3.1 Priming: Automatic/Independent of Attention? 626 2.33.3.2 Priming: Modulated by Attention 627 2.33.3.3 Neural Mechanisms of Top-Down Attentional Modulation 629 2.33.4 Specificity of Priming 630 2.33.4.1 Stimulus Specificity 630 2.33.4.2 Associative Specificity 632 2.33.4.3 Response Specificity 632 2.33.5 Priming-Related Increases in Neural Activation 634 2.33.5.1 Negative Priming 634 2.33.5.2 Familiar Versus Unfamiliar Stimuli 635 2.33.5.3 Sensitivity Versus Bias 636 2.33.6 Correlations between Behavioral and Neural Priming 637 2.33.7 Summary and Conclusions 640 References 641 2.33.1 Introduction stimulus that result from a previous encounter with the same or a related stimulus. Priming refers to an improvement or change in the When considering the link between behavioral identification, production, or classification of a stim- and neural priming, it is important to acknowledge ulus as a result of a prior encounter with the same or that functional neuroimaging relies on a number of a related stimulus (Tulving and Schacter, 1990). underlying assumptions. First, changes in informa- Cognitive and neuropsychological evidence indi- tion processing result in changes in neural activity cates that priming reflects the operation of implicit within brain regions subserving these processing or nonconscious processes that can be dissociated operations. -

Implicit Learning, Development, and Education

Implicit learning, development, and education A. Vinter, S. Pacton, A. Witt and P. Perruchet Introduction The present chapter focuses on implicit learning processes, and aims at showing that these processes could be used to design new methods of education or reeducation. After a brief definition of what we intend by implicit learning, we will show that these proc- esses operate efficiently in development, from infancy to aging. Then, we will discuss the question of their resistance to neurological or psychiatric diseases. Finally, in a last section, we will comment on their potential use within an applied perspective. The fundamental role of learning, once neglected by cognitive psychologists a few decades ago, is now acknowledged in most areas of research, including language, cate- gorization and object perception (2). Of course, nobody has ever claimed that language development is independent of infants’ experience. However, the dominant Chom- skian tradition has confined learning to subsidiary functions, such as setting the values of parameters in a hardwired system. Recent work shows that fundamental components of language such as word segmentation (69) can be learned in an incidental way similar to that involved in the acquisition of other human abilities. Likewise, it has never been denied that learning plays a role in categorization and object perception, but acquisition processes were thought to be limited to new combinations of preestablished features (7). However, Schyns and Rodet (77) have shown that elementary features can them- selves be created with experience (for a review, see 74, 75). The type of learning process that receives the most attention in the current literature relates to implicit learning. -

Book Chapter V2 History

THE HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY 1 Title The History of Developmental Psychology Authors Moritz M. Daum1,2 & Mirella Manfredi1 Affiliations 1University of Zurich, Department of Psychology, Developmental Psychology: Infancy and Childhood 2University of Zurich, Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development Address of correspondence Moritz M. Daum, University of Zurich, Department of Psychology, Developmental Psychology: Infancy and Childhood, Binzmuehlestrasse 14, Box 21, CH-8050 Zurich, Switzerland. Phone: +41 (0)44 635 74 86, E-Mail: [email protected] ORCID IDs Moritz M. Daum: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4032-4574 Mirella Manfredi: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6549-1993 THE HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY 2 Introduction The authors of this paper were invited to provide a chapter on how to teach “Developmental Psychology” (Daum & Manfredi, forthcoming) to the “International Handbook of Psychology Learning and Teaching” (Zumbach et al., forthcoming). When writing, the authors got lost in the details and wrote just a tiny little bit more than the editors asked for. In the end, we had to cut a substantial part of the chapter and decided to delete entire sections, one of them was the part on the “History of Developmental Psychology”. We nevertheless thought that the section could be of interest to somebody out there and put it as a preprint on the open science platform PsyArXiv. Enjoy reading. The History of Developmental Psychology Following the quote attributed to Goethe: “If you want to know how something is, you must look at how it came to be”, the goal of this section is to embed current views on development into a larger historical perspective.