Toronto, Ont. — 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan

Attachment 1: Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan IE8.7 - Attachment 1 AUTOMATED VEHICLES TACTICAL PLANDRAFT INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK DRAFT ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document is the result of guidance, feedback and support from a number of individuals and organizations. In the development of this Automated Vehicles Tactical Plan, the City of Toronto hosted many stakeholder workshops and one-on-one meetings, consulted panels, and provided an open call for feedback via surveys and public posting. Responses were provided by academic institutions, industry representatives, community associations, City staff, advocacy groups, neighbouring municipalities, members of the public and international experts – among other stakeholders. A special thank you to the 2018 Toronto Planning Review Panel, the 2019 Accessibility Advisory Committee, and the 2019 Expert Review Panel hosted by the Ontario Centres of Excellence for their detailed feedback on the AV Tactical Plan. Expert Review Panel Members Emiko Atherton Anthony Townsend Director National Complete Streets Principal Consultant and Author, Bits Coalition, Smart Growth America and Atoms LLC (New York City, NY) (Washington, DC) Dr. Tom Vöge Ann Cavoukian Policy Analyst Intelligent Transport Distinguished Expert-in-Residence, Systems, Organization for Economic Privacy by Design Centre of Cooperation and Development – Excellence, Ryerson University International Transport Forum (Paris, (Toronto, ON) France) Rita Excell Bryant Walker Smith Executive Director, Australia and New Assistant Professor School of -

Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate Under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street

REPORT FOR ACTION Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street Date: August 7, 2020 To: Toronto Preservation Board Toronto and East York Community Council From: Senior Manager, Heritage Planning, Urban Design, City Planning Wards: Ward 11 - University-Rosedale SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council state its intention to designate the property at 100 College Street under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act and include the property on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. The Banting Institute at 100 College Street, is located on the north side of College Street in Toronto's Discovery District, on the southern edge of the Queen's Park/University of Toronto precinct, opposite the MaRS complex and the former Toronto General Hospital. Following the Nobel-Prize winning discovery of insulin as a life- saving treatment for diabetes in 1921-1922, the Banting Institute was commissioned by the University of Toronto to accommodate the provincially-funded Banting and Best Chair of Medical Research. Named for Major Sir Charles Banting, the five-and-a-half storey, Georgian Revival style building was constructed according to the designs of the renowned architectural firm of Darling of Pearson in 1928-1930. The importance of the historic discovery was recently reiterated in UNESCO's 2013 inscription of the discovery of insulin on its 'Memory of the World Register' as "one of the most significant medical discoveries of the twentieth century and … of incalculable value to the world community."1 Following research and evaluation, it has been determined that the property meets Ontario Regulation 9/06, which sets out the criteria prescribed for municipal designation under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, for its design/physical, historical/associative and contextual value. -

Jane Finch Mission Centre

JANE FINCH MISSION CENTRE Feasibility Study & Business Case Report For the University Presbyterian Church unit a architecture inc. / February 05, 2014 PG TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Tables & Figures 6 0.0 Introduction 0.1 The Need for a Feasibility Study and Business Case 0.2 Objectives 0.3 Vision 10 1.0 Site Description 1.1 Development Characteristics 1.2 Environmental Analysis 1.3 Traffic Analysis 1.4 Regulations and Environmental Issues 1.5 Site Analysis 1.6 Zoning Code Analysis 1.7 Building Code Analysis 20 2.0 Case Studies 2.1 Urban Arts 2.2 Evangel Hall Mission 2.3 Pathways to Education 2.4 Regent Park School of Music 28 3.0 Environment 3.1 Priority Investment Neighbourhood 3.2 Housing 3.3 Conflict 36 4.0 Service Infrastructure 4.1 Access to Service Providers 4.2 Music Services 42 5.0 Investment Options 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Existing Facilities Review 5.3 Existing Church Building Use 5.4 New Investment 5.5 Schematic Design 60 6.0 Business Models 6.1 UPC Designs-Finances-Builds-Operates Facility 6.2 UPC Designs-Finances-Builds New Facility and Operates Church, Third Party Operates Nutritional, Homework and Music Services 6.3 New Jane Finch Mission Board Designs-Finances-Builds and Operates Facility 6.4 Sponsorships 6.5 Conclusion 2 66 7.0 Financial Projections 7.1 LEED Cost-Benefit Analysis 7.2 Capital Costs 7.3 Revenue Centres 7.4 Operating Expenses 7.5 Five-Year Pro-forma Projections 7.6 Project Costs Breakdown 78 8.0 Implementation 8.1 Implementation of the Project 82 9.0 Recommendations 9.1 Alternative 1: Do not proceed with construction of the Jane Finch Mission Centre. -

1997Fcprogram.Pdf

THE MIMCO MOUNTAINEERS WOULD LIKE TO THANK THEIR 1997 SPONSORS FOR THEIR SUPPORT Apps ExpressCartage Apps International Logistics Artex Electrical Bestway Cartage 1997 Consolidated Freightways Canadian Junior 'B' Lacrosse Championships Cutler-Hamer Etobicole Professional Fire Fighter's Association HOST COMMITTEE Fonorola Co-Chair jim Surphlis Co-Chair Sean O'Callaghan Gillespie-Munroe Event Coordinators ". Rob Michalsky · Brian Shanahan G "N" R Pro Shop · Mark Grimes Homelife Realty - Betty Bailey ................................ john Robinson Hub Group Canada · Bernie Sauve · jack Foote Kingsway Landscaping · Christine Neary Laser 1000 - Margaret McGonigle Volunter Coordinator Lynda O'Callaghan Lazer-Tech Limited VOLUNTEERS Lex Metal Ltd. Kelly O'Cailaghan joe O'Callaghan Brenda Borrow Liberty Health Howie Borrow Sheila Petrovic Darlene Priestman Michelle Robinson Ginette Surphlis Bob McCabe McDonald's Restaurants of Canada Scottie Gillingham Rick Ellul Roger McKeen Midland Walwyn Bill McAlpine Sarah Calvert Nicole Sauve Mimico-Lakeshore Lacrosse Alumni Gord Mackenzie Mick jenkins Mimico Pharmacy Mimico Minor Lacrosse Club CANADIAN LACROSSEASSOCIATION Chairman of the Board Bill Hutton Technical Director Mike Lachapelle Motorola Vice-President, Technical jim Price Neulaps Automotive PennLife Corp Insurance ONTARIO JUNIOR 'B' COUNCIL Commissioner Dave Vernon Pristine Printi ng Secretary-Treasurer Vince Ladouceur Queensway Minor Hockey Association CITY OF ETOBICOKE Rick's Tree Maintenance Director of Facilities Bill Channing R.B. Bannon Canada Royal LePage- Angela and Paul Giruady MIMICO ARE A STAFF Manager Don Thompason Sky Tracker of Canada Assistant Manager Ivan Krympotich Systemsearch Maintenance Clay Stewart The Blue Goose Tavern .......................... Peter King Total Auto Glass WhiteOak Lincoln Mercury Mimico's own Brendan Shanahan of the Stanley Cup winning Detroit Red Wings and Brian Shanahan, of the Mann Cup Champion Six Nations Chiefs pose with their respective trophies, the Stanley and Mann Cups. -

Toronto's Waterfront Is New Destination for Mars Innovation

Toronto’s Waterfront is new destination for MaRS innovation hub TORONTO, September TK, 2018 — MaRS Discovery District together with partner University of Toronto today announced that they are finalizing a lease with Menkes Developments Ltd. (“Menkes”) for a new 24,000-square-foot hub at Toronto’s Waterfront Innovation Centre. Already under construction,The Waterfront Innovation Centre will deliver critically needed office space for Toronto’s fast-growing innovation community in close proximity to the city’s thriving Discovery District. “As Toronto becomes a premiere destination for global talent, venture capital and tech corporations, demand for space is at an all-time high. It’s imperative that we develop new innovative and entrepreneurial hubs in communities across the city,” says Yung Wu, CEO of MaRS. “The Waterfront Innovation Centre is the next destination for the city’s growing innovation sector — one that will further solidify Toronto’s standing as a premiere tech centre.” When opened in 2021, the Waterfront Innovation Centre, developed by Menkes in partnership with Waterfront Toronto will create approximately 400,000 square feet of office space and accomodate an estimated 3,000 workers. “The University of Toronto is excited to once again partner with MaRS to help expand Toronto’s rapidly growing innovation scene on the city’s waterfront,” says Meric Gertler, U of T President. “It’s a winning combination — MaRS’s world-class suite of innovation programming and expert support for entrepreneurship with the incredible depth and range of U of T’s globally renowned researchers.” “Toronto is experiencing its lowest office vacancy rate ever (three per cent), making the Toronto office space the most in-demand market in North America,” Wu says. -

To Discovery District 101 COLLEGE STREET: at the HEART of CANADA's HEALTH CARE HERITAGE

From "The Ward" to Discovery District 101 COLLEGE STREET: AT THE HEART OF CANADA'S HEALTH CARE HERITAGE A Heritage Report for MaRS (Medical and Related Sciences Discovery District) 149 College Street, Suite 501, Toronto, ON, M5T 1P5 By Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D. HEALTH HERITAGE RESEARCH SERVICES http://www.healthheritageresearch.com August 2002 On April 11, 1911, at the cornerstone ceremony of the new Toronto General Hospital at 101 College Street, the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario made a significant comment. "The recovery of over ten acres of land in the College-Elizabeth-Hayter-Christopher section of the historic 'Ward,' and the devotion of so large an area to the uses and requirements of a hospital is nothing short of an event in the history of this city." Over 90 years later, and after many significant medical events within the walls of Toronto General Hospital, particularly the main College Wing, the Lieutenant-Governor's words MaRS - 101 College St Health Heritage Report Page 2 Rutty, C.J. - August 2002 are again relevant to a significant new phase in the history of the former "Ward" site. The new mission will be very much entwined with the 101 College Street building, to be called the "Heritage Building," as the centerpiece of the redeveloped site known as the "Discovery District for Medical and Related Sciences," or simply MaRS. Since its official opening on June 18, 1913, and through most of the 20th century, the TGH College Wing stood at the centre of a dynamic discovery district not unlike the new "Discovery District" envisioned by MaRS. -

MATT ,ESS [Et: 1 12 E -R 2 Lynden Rd -Ter Ieret -184 Lynden Road, I( DELIVERY Lyndon MATTRESS BRANDS Park Mall Mattress Ilk BRANTFORD Brands Int

.r, . Y t-ter T LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA 1 t Bibliot leque et Archives Canada tJSvR,NA s1oS 11 II II I! II I I II 111 3 32 6 53873950 5 T-j y I 19 Library & Archives ana. a Newspaper Collection l r 74 i 395 Wellington St. North America's #1 Native W Ottawa. ON K1A ON4 Pub. No. 40016309 Kids have fun while learning at Bite of Brant I Reg. No. 10963 ...See page 7 Okarahshona kenh Onkwehonwene, Six Nations of the Grand Wednesday April 16, 2008 Confederacy mulls over 4 Ontario's `no go zone' i offer I .4 M By Mark Ladan Sd.a - Z «evgr,!'.:; Writer The Six Nations Confederacy council wants more informa- tion before making a decision on an Ontario offer of a two - year development moratorium within the Haldimand Tract. Lead provincial negotiator Murray banned for two years. Coolican made the offer when he The Confederacy Chiefs further 1 spoke at the council's Apr. 5 meet- discussed the matter at a special 11 ing. meeting of the council on Apr. 11. 'il Coolican suggested that any devel- Cayuga sub -Chief Leroy Hill said opment currently underway within it has been deferred to the six - 't the Tract should be allowed to pro- member Chiefs committee that has t ceed, but the Confederacy council been appointed to oversee the land would be allowed to draw up a list rights negotiating process. of so- called "no go zones," in which development would be (Continued on page 3) Ve "Sick" school shut down, ti students moved . -

Round 1 - Pick 1

Round 1 - Pick 1 OJALL ontario junior ‘a’ lacrosse league Jeff teat Brampton Excelsiors Round 1 - Pick 3 Round 1 - Pick 5 Round 1 - Pick 6 Round 1 - Pick 7 Round 1 - Pick 8 Round 1 - Pick 10 Round 1 - Pick 11 RYAN SMITH TANNER COOK ROBERT HUDSON MARSHALL POWELESS JEFF HENRICK ETHAN WALKER ETHAN RIGGS OAKVILLE ROCK WHITBY WARRIORS BRAMPTON EXCELSIORS SIX NATIONS ARROWS ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN PETERBOROUGH LAKERS BURLINGTON CHIEFS Round 1 - Pick 12 Round 1 - Pick 15 Round 1 - Pick 16 Round 2 - Pick 17 Round 2 - Pick 18 Round 2 - Pick 23 Round 2 - Pick 24 CONNOR MCLELLAND MAC O’KEEFE JACKSON SUBOCH MATHIEU BOISSONNEAULT RON JOHN JORDAN STOUROS CHARLIE KITCHEN Brampton Excelsiors ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN BROOKLIN LC WHITBY WARRIORS SIX NATIONS ARROWS PETERBOROUGH LAKERS TORONTO BEACHES Round 2 - Pick 25 Round 2 - Pick 29 Round 3 - Pick 38 Round 3 - Pick 39 Round 3 - Pick 40 Round 3 - Pick 44 Round 3 - Pick 46 TY THOMPSON ANDREW BORGATTI KEVIN OWEN HILL SAM FIRTH CURTIS CONLEY ADAM KROMER PHIL MAZZUCA NEPEAN KNIGHTS KITCHENER BRAVES SIX NATIONS ARROWS ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN TORONTO BEACHES WHITBY WARRIORS OAKVILLE BUZZ Round 3 - Pick 47 Round 3 - Pick 48 Round 3 - Pick 51 Round 4 - Pick 53 Round 4 - Pick 54 Round 4 - Pick 56 Round 4 - Pick 57 LACROSSE MATT GAUDET OWEN FRIESEN BEN FRENCH KRIS VELTMAN MITCH OGILVIE ROBBIE STOVEL JONAH BOEHM MIMICO MOUNTAINEERS ST. CATHARINES ATHLETICS COBOURG KODIAKS WEST DURHAM IRONHEADS PETERBOROUGH LAKERS Brampton Excelsiors KITCHENER BRAVES Round 4 - Pick 60 Round 4 - Pick 62 Round 4 - Pick 63 Round 4 - Pick 67 Round 5 - Pick 70 Round 5 - Pick 73 Round 5 - Pick 74 TANNER BUCK CHRIS WEIER brody mclean curtis romanchych john vezina tye argent john kit ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN Niagara thunderhawks kitchener braves orangeville northmen Brampton Excelsiors hamilton bengals st. -

Tamarack Donors and Contributors – 2018

Tamarack Donors and Contributors – 2018 Over $100,000 Anonymous Donor Employment and Social Development Canada Maytree Foundation McConnell Foundation Ontario Trillium Foundation Suncor Energy Foundation $100,000 to $10,000 Alberta Health Services City of Edmonton Futureworx Greater Vancouver Foodbank Hamilton Community Foundation The Young Fund Howard County Multiservice Centre JSI Research & Training Institute Kahnawake Economic Development MaRS Discovery District Mental Health Commission of Canada Nectar Creative Communications Northern Illinois Center for Nonprofit Excellence Ontario Greenhouse Vegetable Growers Pathways to Education Canada Science World BC Tenacious Change Toronto Community Housing Corporation United Way of Greater Atlanta United Way of the Greater Lehigh Valley Vancouver Foundation Zero to Three $10,000 to $5,000 Bertelsmann Stiftung City of Grande Prairie City of Kitchener City of Prince George City of Vancouver Collaboration for Impact Columbia Basin Trust Deltager Danmark End Poverty Edmonton Environmental Appeals Board with the Dispute Resolution Network FuseSocial Government of Nova Scotia Langley Association for Community Living L'Arche Stratford National Coucil of the United States Society of St Vincent de Paul, Inc. New Brunswick Women's Council Parkinson Association of Alberta Peel Children's Centre Peel Poverty Reduction Strategy Pictou County United Way Rainy River District Social Services Administration Board REACH Edmonton Council Region of Peel Strathcona County Family and Community Services The Sinneave -

Ocad University

Duerin Ossington YORKVILLE M M M M M M Bloor West M M M M Bloor East KOREA STUDENT RESIDENCE OPTIONS TOWN Yonge Huron Bathurst Grace Charles 1. Campus Common St. George St. Spadina 2. Campus Co-Operative Residence Inc M Park Queen’s 3. CampusOne 4. Neill-Wycik Co-op and Hotel Hoskin 5. Parkside Student Residence Harbord Bay 6. YWCA Housing Gloucester LITTLE CULTURAL ATTRACTIONS QUEEN’S Church UNIVERSITY PARK Jarvis 7. Art Gallery of Ontario ITALY OF M Wellesley 8. Artscape Youngplace TORONTO 9. Bata Shoe Museum 10. Campbell House Museum THE 11. Centre for Social Innovation – Annex BROCKTON VILLAGE 12. Centre for Social Innovation – Spadina College 13. Dundas Square VILLAGE H (LGBTQ+) 14. Ed Mirvish Theatre 15. Elgin and Winter Garden Theatre Centre College M M 16. Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts LITTLE Carlton 17. Gardiner Museum Spadina PORTUGAL Oxford 18. Harbourfront H 19. MaRS Discovery District KENSINGTON H COLLEGE 20. Michener Institute Nassau MARKET PARK Mutual H Gerrard 21. Princess of Wales Theatre Shaw Baldwin 22. Queen’s Park H H Bellevue H RYERSON 23. Roy Thomson Hall Elm UNIVERSITY Ossington 24. Royal Alexandra Theatre Dundas West Augusta Gould Lansdowne Duerin Jarvis 25. Royal Conservatory of Music Beverley Brock 26. Royal Ontario Museum Dundas West M 27. Ryerson Image Arts Centre M 28. Textile Museum of Canada CHINATOWN McCaul Dundas TRINITY 29. TIFF Bell Lightbox Bay OSSINGTON BELLWOODS 30. Toronto City Hall PARK GALLERY PARK Gladstone Church 31. Toronto Eaton Centre DISTRICT GRANGE University Beaconsfield 32. University of Toronto Art Centre Bathurst 33. -

OUA/CIS ELIGIBILITY CERTIFICATE the University of Western Ontario

OUA/CIS ELIGIBILITY CERTIFICATE The University of Western Ontario SPORT: Men's Lacrosse YEAR: 2018-19 A - Addition * - Inactive A/* # First Name Last Name ELIG YR COURSE YEAR HOMETOWN PROV LAST TEAM Spencer Allen 1 Huron College 2 Toronto ON Strathroy Rockets Cody Arseneault 2 Social Sciences 2 Calgary AB Calgary Jr.A Mounties and Elev8 Lacrosse Mackenzie Burns 2 Social Sciences 2 Burnaby BC Burnaby Lakers Jr. A Lacrosse Michael Byrne 4 BMOS 4 Toronto ON St. Michael's Blue Gaels Toronto Beaches Jr. A William Carnduff 1 Social Sciences 1 Whitby ON Team Ontario Keagan Croley 4 BMOS 4 London ON London U19 lacrosse Cole Davis 3 Kinesiology 4 Halifax NS Team Nova Scotia Lacrosse Kevin Dong 2 Sciences 2 Oakville ON Oakville Buzz Liam Dunn 1 Social Sciences 1 Toronto ON UCC varsity lacrosse Nikolai Farrus 5 Graduate Studies 1 Edmonton AB St. Albert Miners Jr.A Lacrosse Jamie Finlay 2 Social Sciences 3 Aurora ON London Jr. Mustangs U19 Patrick Gamble 4 King's College 4 Oakville ON Oakville Buzz, Holy Trinity Titans Liam Gant 3 BMOS 3 Orangeville ON Northern Lacrosse, and Orangeville Generals Joshua Goodwin 3 Social Sciences 3 Newmarket ON Newmarket Saints Junior B Jon Greig 1 Kinesiology 1 Delta BC Ladner pioneers Austin Haber 5 Business 4 Toronto ON UCC Varsity Lacrosse Lyle Hill 1 Arts 2 Six Nations ON Six Nations Rebels Gabriel Iozzo 1 Social Sciences 2 Mississauga ON St Aloysius Gonzaga highschool Director of Athletics or Designate: Date: ________________________________ Registrar or Designate: ___________________________________ Date: _____________________ Coach:________________________________________ Date:__________________________ *The information collected in this form is used and disclosed by Canadian Interuniversity Sport (“CIS”) in accordance with the terms of CIS’ Student Athlete Acknowledgement Form and CIS’ Personal Information Protection Policy. -

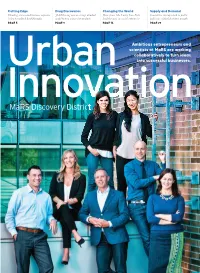

Mars Report Urban Innovation.Pdf

Cutting Edge Drug Discoveries Changing the World Supply and Demand Blending science and business expertise JLABS using new no-strings-attached How firms like Lucky Iron Fish Innovative startups look to public is key to medtech breakthroughs model to turn science into products lead the way in social enterprise policy as critical to future growth PAGE 5 PAGE 9 PAGE 16 PAGE 29 Ambitious entrepreneurs and scientists at MaRS are working collaboratively to turn ideas Urban into successful businesses. Innovation MaRS Discovery District MaRS_Magazine_FINAL.indd 1 2016-10-05 4:40 PM DM172089_PgOFC_MaRS_NOV_2016.indd 1 16-10-06 10:08 AM INNOVATION But we also face challenges. Our long reliance on resource extraction and imported technology has resulted in an economy with low IS THE business research-and-development spending and poor performance in commercializing intellectual capital. On the positive side, Toronto, FUNDAMENTAL Montreal and Vancouver have all been drawing international notice as innovation regions. They also deserve domestic attention for two reasons. QUEST FOR First, Canada is one of the most urbanized nations of the world, with a massively disproportionate share of national income generated in and HUMAN around those three major cities. Second, international data shows that innovation is a process that runs best with an urban engine. PROGRESS In particular, urban regions have a huge scale advantage BY ILSE TREURNICHT, CEO, MaRS DISCOVERY DISTRICT in convergent innovation, exemplified by various fields, such as precision medicine, nnovation is a word “Our greatest advantage advanced materials, financial one hears often these technology, artificial intelligence days — perhaps too lies in our cities.