F • High Accuracy Sonographic Recognition of Gallstones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focal Spot, Spring 2006

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Focal Spot Archives Focal Spot Spring 2006 Focal Spot, Spring 2006 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/focal_spot_archives Recommended Citation Focal Spot, Spring 2006, April 2006. Bernard Becker Medical Library Archives. Washington University School of Medicine. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Focal Spot at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Focal Spot Archives by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPRING 2006 VOLUME 37, NUMBER 1 *eiN* i*^ MALLINCKRC RADIOLO AJIVERSITY *\ irtual Colonoscopy: a Lifesaving Technology ^.IIMi.|j|IUII'jd-H..l.i.|i|.llJ.lii|.|.M.; 3 2201 20C n « ■ m "■ ■ r. -1 -1 NTENTS FOCAL SPOT SPRING 2006 VOLUME 37, NUMBER 1 MIR: 75 YEARS OF RADIOLOGY EXPERIENCE In the early 1900s, radiology was considered by most medical practitioners as nothing more than photography. In this 75th year of Mallinckrodt Institute's existence, the first of a three-part series of articles will chronicle the rapid advancement of radiol- ogy at Washington University and the emergence of MIR as a world leader in the field of radiology. THE METABOLISM OF THE DIABETIC HEART More diabetic patients die from cardiovascular disease than from any other cause. Researchers in the Institute's Cardiovascular Imaging Laboratory are finding that the heart's metabolism may be one of the primary mechanisms by which diseases such as diabetes have a detrimental effect on heart function. VIRTUAL C0L0N0SC0PY: A LIFESAVING TECHNOLOGY More than 55,000 Americans die each year from cancers of the colon and rectum. -

Imaging in Double Gall Bladder with Acute Cholecystitis—A Rare Entity

Surgical Science, 2014, 5, 273-279 Published Online July 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ss.2014.57047 Imaging in Double Gall Bladder with Acute Cholecystitis—A Rare Entity Praveen Kumar Vasanthraj, Rajoo Ramachandran, Kumaresh Athiyappan, Anupama Chandrasekharan, Cunnigaiper Dhanasekaran Narayanan Department of Radiology, Sri Ramachandra University, Chennai, India Email: [email protected] Received 28 April 2014; revised 26 May 2014; accepted 22 June 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Duplication of gall bladder is a rare congenital anomaly of the hepatobiliary system. It is a very important entity in clinical practice as preoperative diagnosis plays a significant role in the man- agement and to avoid unnecessary bile duct injury during surgery. We report a case of duplicated gall bladder presenting as acute cholecystitis. Keywords Gall Bladder, Duplication, Cholecystitis 1. Introduction Gall bladder (GB) duplication is a rare congenital anomaly of hepatobiliary system with a reported incidence of about 1 per 4000 autopsies [1]. Duplication of gall bladder and their varying anatomical positions are associated with an increased risk of complications including biliary leak after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy [2]-[5]. 2. Case Presentation A 45 years old lady presented with complaints of abdomen pain for the past two days. It was colicky type pain, intermittent in nature and localized to the right hypochondrium. She also gave history of three episodes of vo- miting which was non bilious, non blood stained and non foul smelling. -

Cholecystokinin Cholescintigraphy: Methodology and Normal Values Using a Lactose-Free Fatty-Meal Food Supplement

Cholecystokinin Cholescintigraphy: Methodology and Normal Values Using a Lactose-Free Fatty-Meal Food Supplement Harvey A. Ziessman, MD; Douglas A. Jones, MD; Larry R. Muenz, PhD; and Anup K. Agarval, MS Department of Radiology, Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC Fatty meals have been used by investigators and clini- The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the use of a cians over the years to evaluate gallbladder contraction in commercially available lactose-free fatty-meal food supple- conjunction with oral cholecystography, ultrasonography, ment, as an alternative to sincalide cholescintigraphy, to de- and cholescintigraphy. Proponents assert that fatty meals velop a standard methodology, and to determine normal gall- are physiologic and low in cost. Numerous different fatty bladder ejection fractions (GBEFs) for this supplement. meals have been used. Many are institution specific. Meth- Methods: Twenty healthy volunteers all had negative medical histories for hepatobiliary and gallbladder disease, had no per- odologies have differed, and few investigations have stud- sonal or family history of hepatobiliary disease, and were not ied a sufficient number of subjects to establish valid normal taking any medication known to affect gallbladder emptying. All GBEFs for the specific meal. Whole milk and half-and-half were prescreened with a complete blood cell count, compre- have the advantage of being simple to prepare and admin- hensive metabolic profile, gallbladder and liver ultrasonography, ister (4–7). Milk has been particularly well investigated. and conventional cholescintigraphy. Three of the 20 subjects Large numbers of healthy subjects have been studied, a were eliminated from the final analysis because of an abnormal- clear methodology described, and normal values determined ity in one of the above studies. -

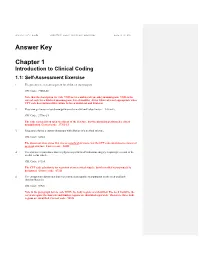

Answer Key Chapter 1

Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 1 of 101 Answer Key Chapter 1 Introduction to Clinical Coding 1.1: Self-Assessment Exercise 1. The patient is seen as an outpatient for a bilateral mammogram. CPT Code: 77055-50 Note that the description for code 77055 is for a unilateral (one side) mammogram. 77056 is the correct code for a bilateral mammogram. Use of modifier -50 for bilateral is not appropriate when CPT code descriptions differentiate between unilateral and bilateral. 2. Physician performs a closed manipulation of a medial malleolus fracture—left ankle. CPT Code: 27766-LT The code represents an open treatment of the fracture, but the physician performed a closed manipulation. Correct code: 27762-LT 3. Surgeon performs a cystourethroscopy with dilation of a urethral stricture. CPT Code: 52341 The documentation states that it was a urethral stricture, but the CPT code identifies treatment of ureteral stricture. Correct code: 52281 4. The operative report states that the physician performed Strabismus surgery, requiring resection of the medial rectus muscle. CPT Code: 67314 The CPT code selection is for resection of one vertical muscle, but the medial rectus muscle is horizontal. Correct code: 67311 5. The chiropractor documents that he performed osteopathic manipulation on the neck and back (lumbar/thoracic). CPT Code: 98925 Note in the paragraph before code 98925, the body regions are identified. The neck would be the cervical region; the thoracic and lumbar regions are identified separately. Therefore, three body regions are identified. Correct code: 98926 Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 2 of 101 6. -

Chapter One General Introduction

Chapter One General Introduction 1.1Introduction: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an abdominal magnetic resonance imaging method that allows non-invasive visualization of the pancreatobiliary tree and requires no administration of contrast agent. (Adamek HE et al, 1998). MRCP is increasingly being used as a non-invasive alternative to ERCP and a high percentage of the diagnostic results of MRCP are comparable with those from ERCP for various hepatobiliary pathologies. (Vogl TJ et al.2006). It has been exactly two decades since magnetic resonancecholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was first described. Over this time, the technique has evolved considerably, aided by improvements in spatial resolution and speed of acquisition. It has now an established role in the investigation of many biliary disorders, serving as a non-invasive alternative to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).It makes use of heavily T2-weighted pulse sequences, thus exploiting the inherent differences in the T2-weighted contrast between stationary fluid-filled structures in the abdomen (which have a long T2 relaxation time) and adjacent soft tissue (which has a much shorter T2 relaxation time). Static or slow moving fluids within the biliary tree and pancreatic duct appear of high signal intensity on MRCP, whilst surrounding tissue is of reduced signal intensity. (WallnerBK ,et al 1991). 1 Heavily T2-weighted images were originally achieved using a gradient-echo (GRE) balanced steady-state free precession technique. A fast spin-echo (FSE) pulse sequence with a long echo time (TE) was then introduced shortly after, with the advantages of a higher signal-to-noise ratio and contrast-to-noise ratio, and a lower sensitivity to motion and susceptibility artefacts. -

Ultrasonography in Hepatobiliary Diseases

Ultrasonography in Hepatobiliary diseases Pages with reference to book, From 189 To 194 Kunio Okuda ( Department of Medicine, Chiba University School of Medicine, Chiba, Japan (280). ) Introduction of real-time linear scan ultrasonography to clinical practice has revolutionalized the diagnostic approach to hepatobiiary disorders. 1 This modality allows the operator to scan the liver and biliary tract with a real-time effect, and obtain three dimensional images. One can follow vessels and ducts from one end to the other. The portal and hepatic venous systems are readily seen and distinguished. Real-time ultrasonography (US) using an electronically activated linear array transducer is becoming a stethoscope for the liver specialist, because a portable size real-time ültrasonograph is already available. It is now established that real-time US is useful not only in the diagnosis of gallstones, dilatation of the biliary tract, and cystic lesions, but it can also assess liver parenchyma in various diffuse liver diseases. Thus, a wide range of diffuse liver diseases beside localized hepatic lesions can he evaluated by US. It can also make the diagnosis of portal hypertension 2-4 In our unit, the patient with a suspected hepatobiiary disorder is examined by US on the first day of hospital visit, and the next investigation that will pOssibly provide a definitive diagnosis, such as ERCP, PTC, X-ray CT, angiography, scintigraphy, etc., is scheduled. Using a specially designed transducer, a needle can be guided while the vessel, a duct, or a structure is being aimed and entered (US-guided puncture). 5 ;7 US-guided puncture technique has improved the procedure for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogrpahy 8, biliary decompression, percutaneous transhepatic catheterizatiøn for portography 9, and obliteration of bleeding varices. -

Colorectal T91-T105 W89 T91

Gut 1995; 36 (suppl 1) A23 Colorectal T91-T105 W89 T91 LANSOPRAZOLE PROVIDES GREATER SYMPTOM RELIEF THAN COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING: THE EFFECT OF OMEPRAZOLE IN REFLUX OESOPHAGITIS. A S Mee, J L Rowley COMBINING FLEXIBLE SIGMOIDOSCOPY WITH A FAECAL Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.36.Suppl_1.A23 on 1 January 1995. Downloaded from and the Lansoprazole Study Group; Royal Berkshire & Battle OCCULT BLOOD TEST. D H Bennett, M R Robinson, P Preece, V Moshakis, Hospitals NHS Trust, Reading, RG1 SAN, UK. K D Vellacott, S Besbeas, J Kewenter, 0 Kronborg, S Moss, J Chamberlain & J D Hardcastle; Lansoprazole, a second generation proton pump inhibitor, provides Department of Surgery, University Hospital, effective symptom relief and healing in reflux oesophagitis. Its greater Nottingham NG7 2UH. bioavailability compared to omeprazole results in superior initial acid suppression. This study was to compare symptom relief and The role of endoscopy in colorectal cancer designed screening is currently under discussion. A healing rates in patients with reflux oesophagitis. prospective, randomised European study is in Methods 604 patients with endoscopically proven reflux progress assessing the benefit of combining oesophagitis, were randomly assigned to receive lansoprazole 30mg or Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (S) with Haemoccult (H) in omeprazole 20mg daily for up to 8 weeks. Daily assessment of screening asymptomatic persons between 50-74 was made the a Visual Scale. years. Subjects were randomised to screening by symptoms by patient using Analogue both S+H (Group 1) or H alone (Group 2). Clinical symptoms were evaluated at weeks 1, 4 and 8. Endoscopic assessment of healing, defined by normalisation of the oesophageal Number Randomised mucosal appearance, was made at weeks 4 and 8. -

Cholescintigraphy Stellingen

M CHOLESCINTIGRAPHY STELLINGEN - • - . • • ' - • i Cholescintigrafie is een non-invasief en betrouwbaar onderzoek in de diagnostiek bij icterische patienten_doch dient desalniettemin als een complementaire en niet als compfititieye studie beschouwd te worden. ]i i Bij de abceptatie voor levensverzekeringen van patienten met ! hypertensie wordt onvoldoende rekening gehouden met de reactie jj op de ingestelde behandeling. ! Ill | Ieder statisch scintigram is een functioneel beeld. | 1 IV ] The purpose of a liver biopsy is not to obtain the maximum \ possible quantity of liver tissue, but to obtain a sufficient 3 quantity with the minimum risk to the patient. j V ( Menghini, 1970 ) I1 Bij post-traumatische verbreding van het mediastinum superius is I angiografisdi onderzoek geindiceerd. VI De diagnostische waarde van een radiologisch of nucleair genees- kundig onderzoek wordt niet alleen bepaald door de kwaliteit van de apparatuur doch voonnamelijk door de deskundigheid van de onderzoeker. VII Ultra sound is whistling in the dark. VIII De opname van arts-assistenten, in opleiding tot specialist, in de C.A.O. van het ziekenhuiswezen is een ramp voor de opleiding. IX De gebruikelijke techniek bij een zogenaamde "highly selective vagotomy" offert meer vagustakken op dan noodzakelijk voor reductie van de zuursecretie. X Het effect van "enhancing" sera op transplantaat overleving is groter wanneer deze sera tijn opgewekt onder azathioprine. XI Gezien de contaminatiegraad van in Nederland verkrijgbare groenten is het gebraik als rauwkost ten stelligste af te raden. j Het het ontstaan van een tweede maligniteit als complicatie van 4 cytostatische therapie bij patienten met non-Hodgkin lymphoma, | maligne granuloom en epitheliale maligne aandoeningen dient, j vooral bij langere overlevingsduur, rekening gehouden te worden. -

Section G: Gastrointestinal System G

Section G: Gastrointestinal system G Clinical/Diagnostic Investigation Recommendation Dose Comment Problem (Grade) G01. Difficulty in Ba Indicated [B] dd Ba esophagogram is the best investigative modality for swallowing: high esophago- diagnosing motility disorders. It is also useful for demonstrat- dysphagia (lesion gram ing webs and pouches and may show subtle strictures not may be high or low) seen at endoscopy. G02. Difficulty in Ba Indicated dd Endoscopy should be performed initially. Ba esophagogram swallowing: low esophago- only in specific should only be performed if endoscopy normal used to dysphagia (lesion gram circumstances [B] demonstrate a motility disorder or a subtle stricture. will be low) G03. Heartburn/ Ba esophago- Indicated dd Reflux is common and can usually be diagnosed clinically. chest pain: hiatus gram /UGI only in specific Investigation is only indicated when medical therapy fails. hernia or reflux circumstances [B] pH monitoring is the gold standard for the diagnosis of reflux, but endoscopy will show early changes of reflux esophagitis and allow biopsy of metaplasia. Section G: Gastrointestinal system Section G: Gastrointestinal Ba esophagogram may be ordered by a surgeon to assess esophageal motility prior to anti-reflux surgery. G04. Esophageal CXR Indicated [B] d A pneumo- mediastinum is present in only 60% of cases, but perforation other suggestive abnormalities may also be seen on a CXR. CT Indicated [A] dd – ddd CT is the best imaging modality for diagnosing esophageal perforation and for the detection of mediastinal and pleural complications. Contrast Indicated [B] dd May be used if CT is not immediately available, but if no leak swallow is seen then proceed to immediate CT. -

WORLD GASTROENTEROLOGY NEWS World Digestive Health Day 2013: LIVER CANCER Act Today. Save Your Life Tomorrow. Editorial

Editorial WORLD GASTROENTEROLOGY NEWS Official e-newsletter of the World Gastroenterology Organisation www.worldgastroenterology.org VOL. 18, ISSUE 1 APRIL 2013 World Digestive Health Day 2013: In this issue LIVER CANCER Act Today. Save Your Life Tomorrow. Awareness. Prevention. Detection. Treatment. Douglas R. LaBrecque, MD, FACP The Future of Colorectal Cancer Professor, Internal Medicine Prevention in Developing Countries University of Iowa Healthcare René Lambert, MD Chairman, WDHD 2013 Steering Committee The World Gastroenterology Organisa- Why liver cancer? Hepatocellular car- tion (WGO) established World Digestive cinoma (HCC, also known as primary Health Day (WDHD) in 2004. Although liver cancer) is variably estimated to be still celebrated on May 29th each year, the fifth to seventh most common cancer The Future of Colorectal Cancer 1,2 Prevention in the United States; the date on which WGO was incorpo- in the world and it continues to be the rated in 1958, WDHD has become a third most common cause of death from A perspective from a high burden, 1,2 sufficient resource country year long, global, public health, advocacy cancer (second most common in men) . Dennis J. Ahnen, MD and awareness campaign. WDHD an- In some countries, it is either the number nually focuses on a specific digestive or one (Mongolia) or number two malignant liver disorder with the goal of increasing neoplasm (China). In the United States awareness by the public, medical practi- of America, it is the fastest rising cancer tioners, government health policy makers, by incidence and death rate3. Every 30 and philanthropic groups of the need for seconds, one person in the world dies prevention, diagnosis and management from liver cancer, which is almost entirely of a specific global health problem. -

Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy of Gallbladder Stones

EXTRACORPOREAL SHOCKWAVE LITHOTRIPSY OF GALLBLADDER STONES EXTRA CORPOREAL SHOCKWAVE LITHOTRIPSY OF GALLBLADDER STONES AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY EXTRACORPORELE SCHOKGOLF L!THOTRIPSIE VAN GALBLAASSTENEN EEN EXPERIMENTELE STUDIE PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof. dr. C.J. Rijnvos en volgens het besluit van het College van Dekanen. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op woensdag 11 december 1991 om 13.45 uur door Hendrik Vergunst geboren te Corsica, SD, USA 1991 Promotiecommissie Promotoren: Prof. dr. O.T. Terpstra Prof. dr. F.H. Schroder Overige !eden: Prof. dr. S.W. Scbalm Prof. dr. ir. CJ. Snijders Aan Lia Arie, Luke, Simone, en Madeline mijnmoeder Ter nagedachtenis aan rnijn vader Financial support by: Siemens Nederland NV ROGAL (Rotterdam Multicenter Gallstone Study) Stichting Urologisch Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (SUWO) Tramedico BV CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLlJKE BIBL!OTHEEK, DEN HAAG Vergunst, Hendrik Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallbladder stones: an experimental study j Hendrik Vergunst.- [S.l.: s.n.].- Ill. Proefschrift Rotterdam. - Met lit. opg. - Met samenvatting in het N ederlands. ISBN 90-9004573-2 Trefw.: galstenen; lithotripsie. Type-setting: E. Ridderhof © 1991, H.Vergunst ISBN 90-9004573-2 Gutta cavat lapidem non vi sed saepe cadendo Ovidius (43 BC- 17 AC) CONTENTS Chapter 1 Background and aims of the study 11 Chapter 2 Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy of gallstones: 17 possibilities and limitations Chapter 3 Assessment -

Medical Imaging Louis Kreel

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.67.786.334 on 1 April 1991. Downloaded from Postgrad Med J (1991) 67, 334 - 346 i) The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1991 Reviews in Medicine Medical imaging Louis Kreel Department ofDiagnostic Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, N. T., Hong Kong Introduction Physicists have tapped the electromagnetic spec- latitude with lower radiation and minimal repeat trum to great effect. Each energy wave-form that examinations. Dark rooms for film processing will penetrates tissues has a corresponding imaging disappear. Fluoroscopy too will be fully automated system, starting with Roentgen's radiograph of his and digitized, and all radiographs will show the full wife's hand in 1895. Since then gamma rays, range of radiodensities from lung, through soft X-rays, protons, ultrasound and radiofrequency tissues to bone with one exposure. This will entail coupled to a magnetic field have been grafted onto new equipment, film, cassettes and imaging systems computers to produce anatomical images varying at considerable expense. in type and detail. More recently these modalities Furthermore, each passing year sees the intro- have produced sophisticated physiological data of duction of new scanners with shorter scanning considerable interest. times and higher spatial resolution, producing Thus the words 'digital' and greater detail and 'computer' have more information. Millisecond copyright. invaded radiology departments, not only with computed tomography (CT), cardiac cine, scanners, of which they are integral components, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) down to but also in conventional fluoroscopy and radio- breath-holding time, and the technology of CT graphy. The change is as revolutionary as that of applied to nuclear medicine (NM), yielding single steam engine to internal combustion engine or photon emission CT and proton emission tomog- automobile to aeroplane.