Whole Thesis 2.0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title ODATE GAME

Title ODATE GAME : character design and modelling for Japanese modesty culture based independent video game Sub Title Author 鄒、琰(Zou, Yan) 太田, 直久(Ota, Naohisa) Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2014 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2014年度メディアデザイン学 第395号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 4-0395 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University Yan Zou A Master's Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Yan Zou Thesis Committee: Professor Naohisa Ohta (Supervisor) Associate Professor Kazunori Sugiura (Co-Supervisor) Associate Professor Nanako Ishido (Co-Supervisor) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Category: Design Summary Game character design is an important part of game design. Game characters cannot be designed only according to the designer's experience or the players' preferences. They should be strongly associated to the game system and also the story. A good game character design is not only the reason for players to purchase the game but it also can improve players' entire game experience. -

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

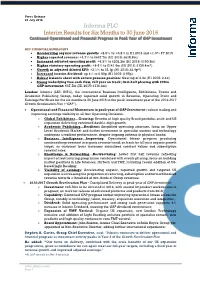

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

Homosexuality As Seen in Grand Theft Auto Iv

HOMOSEXUALITY AS SEEN IN GRAND THEFT AUTO IV A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining The Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: YUNIARTI 10150025 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SUNAN KALIJAGA YOGYAKARTA 2014 ABSTRACT Homosexuality as seen in Grand Theft Auto IV By Yuniarti Grand Theft Auto IV is a form of RPG game created by Rockstar Games in 2008. GTA IV has two additional episodes, namely GTA IV: The Lost and Damned and GTA IV : The Ballad of Gay Tony. The analysis is focused on GTA IV: The Ballad of Gay Tony. This game tells about the life of Tony Prince who has debts taken from his business friends. Since then, Gay Tony asks Luis to do extra work provided by his business friends to redeem the debt. Problems come and go when he tried to redeem his debts and eventually Luis is able to resolve the issue at the end. To analyze Gay Tony, qualitative research method is used to find out how homosexuality is presented by Tony Prince and to reveal how Tony sees himself in being homosexual. The analysis begins with Gay Tony’s homosexual background. Further analysis is divided into several parts, that is conversation of text and visual effects that appear in the game. Conversation was divided into two parts, namely the influence to the other characters and conversations that related to homosexuality. In the visual, the author divides into two, namely the appearance of characters and loading screen image. The writer concludes that the character is an openly homosexual. -

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc. FOR IMMEDIATE 949-788-0455 (x102) RELEASE [email protected] ATLUS U.S.A., INC. ANNOUNCES SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI®: PERSONA 3™ WEBSITE LAUNCH! Locked away in the human psyche is power beyond imagination... IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — JULY 10th, 2007 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading publisher of interactive entertainment, today announced the launch of the official website for Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3! Enormously successful in Japan, P3 is the newest RPG from the publisher of the acclaimed Shin Megami Tensei series. After eight long years of anticipation, fans have very little left to wait. Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 is set to ship on July 24, 2007, exclusively for the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system. Every copy is a deluxe edition with a 52-page color art book and soundtrack CD! Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 has been rated “M” for Mature by the ESRB for Blood, Language, Partial Nudity, and Violence. About Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3: In Persona 3, you’ll assume the role of a high school student, orphaned as a young boy, who’s recently transferred to Gekkoukan High School on Port Island. Shortly after his arrival, he is attacked by creatures of the night known as Shadows. The assault awakens his Persona, Orpheus, from the depths of his subconscious, enabling him to defeat the terrifying foes. He soon discovers that he shares this special ability with other students at his new school. From them, he learns of the Dark Hour, a hidden time that exists between one day and the next, swarming with Shadows. -

Gta 3 Android Cheats Gamekeyboard

Gta 3 android cheats gamekeyboard Continue Download the game keyboard for GTA VC for Android. Keyboard game for GTA VC game Cheater. Vice City Chiter app for GTA Vice CIty. How to start opening GTA 3 ANDROID CHEATS - Game Keyboard Download NewPol. Download Unsubscribe from NewPol? Cancel the unsubscribe. Work Subscription Subscription Unsubscribe 174. Download Download. GTA 3 ANDROID CHEATS GTA 3 ANDROID CHEATS - Game Download Keyboard 552 x 344 1600 Apply Cheats in GTA Vice City for Android Very Easy Is Process K Liye Aap Download Android game Grand Theft Auto Vice City apk. Grand Theft Auto V (GTA 5), pc, pc download, full version of the game, full PC game, compressed, RIp version, before downloading make sure your computer meets the minimum system requirements. Minimum OS requirements: Windows 8.1 64 Bit, Win 8 64 Bit, Win 7 64 Bit Service Pack 1, Win Vista 64 Bit Game Keyboard for GTA VC Game Cheater. Vice City Chiter app for GTA Vice CIty. How to start an open app. Click on Activate Cheater. How to download? If you don't know how to download this game, just click here!. GTA Vice City Bodyguard Download. Click here to download this game size game: 678 MB Password: apunkagames Download GTA III Game Keyboard (Portal. Gnote com) GTA III Game Keyboard (Portal. Gnote com) Type: apk. Download the Android game Grand Theft Auto III apk. Play Grand Theft Auto III game! Download now! You are sure to enjoy its exciting gameplay. October 14, 2013 Grand Theft Auto III For GTA San Andreas cheats, you must download the keyboard to type cheats during the game. -

Art Games Applied to Disability

Figure 1. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2009), Flower. Figure 2. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 4. (2013), Flow. Esther Guanche Dorta. Phd student. [email protected] Ana Marqués Ibáñez. Teacher. [email protected] Department of Didactics of Plastic Expression. Faculty of Education. University of La Laguna. Tenerife. Art Games applied to disability. Figure 3. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2012), Journey. THEME 4 – Technology – S3 DT Art Games, Disabilities, Design, Videogames, Inclusive education. Art Games applied to disability. Videogames are an emerging medium which represent a new form of artistic design, creating another means of expression for artists as well as different educational context adapted to people with dissabilities. Abstract This is a study of several examples of artistic videogames which can be 1. Art Games and Indie Games Concept The MOMA2 arranged an exhibition on the 50 years of videogame history, made a used to improve the quality of life of persons with impairment, for those review about the design and has added the most significant games to its permanent with specific or general motoric disabilities and mental disabilities in Art Game is an art object associated to the new interactive communications media exhibition, such as those of the Johnson Gallery with 14 videogames, which have order to bring them closer to art and design studies. As well as to develop new approaches in order to include this medium in artistic and a subgenre of the so-called serious videogames. The term was first used in been increased to around fifty. productions, study the impact of these images in Visual Culture and its academic circles in 2002, and referred to a videogame designed to boost artistic and construction by designing. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Game Narrative Review

Game Narrative Review ==================== Your name (one name, please): Glenn Winters Your school: Drexel University Your email: [email protected] Month/Year you submitted this review: January 2013 ==================== Game Title: Journey Platform: Playstation 3 Genre: Adventure Release Date: March 13 2012 Developer: ThatGameCompany Publisher: Sony Computer Entertainment Game Writer/Creative Director/Narrative Designer: Director - Jenova Chen, Robin Hunicke - Producer, Nicholas Clark - Designer, Bryan Singh - Designer, Chris Bell - Designer Overview Janet Murray states, “journey stories emphasize navigation -- the transitions between different places, the arrivals and departures -- and the how to’s of the hero’s repeated escapes from danger [4].” At its core, the game Journey encompasses this sense of transitioning and the player character’s rite of passage. It is essentially a “hero’s journey” described in Joseph Cambell’s “The Hero with a Thousand Faces.” In Journey you play as a red robed character whom is often referred to as “the traveler.” The game's narrative revolves around the player’s exploration of the eight different levels as you unravel the history of a once thriving civilization. You collect energy by freeing several “scarf like creatures” that are trapped throughout the world. In this process, the player is challenged by environment driven puzzles and guardians of the past who actively try to capture her energy source before reaching her destination. Different from many other computer games, Journey provides no textual description of the story or dialogues. Thus to convey the story, it relies heavily on visuals and interactions with the environment. In other words, the environment and the resulting visual narrative are crucial narrative elements in addition to the more common storytelling components in the game. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle