Kazi Nazrul Islam Bangla Kobita Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Aradhona' a University of Visual & Performing Arts By

‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS BY IFREET RAHIMA 09108004 SEMINAR II Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelors of Architecture Department of Architecture BRAC University SUMMER 2013 DISSERTATION THE DESIGN OF ‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS This dissertation is submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial gratification of the exigency for the degree of Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch.) at BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh IFREET RAHIMA 09108004 5TH YEAR, DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE BRAC UNIVERSITY, DHAKA FALL 2013 DECLARATION The work contained in this study has not been submitted elsewhere for any other degree or qualification and unless otherwise referenced it is the author’s own work. STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this dissertation rests with the Architecture Discipline. No quotation from it should be published without their consent. RAHIMA | i ‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS A Design Dissertation submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch) under the Faculty of BRAC University, Dhaka. The textual and visual contents of the Design Dissertation are the intellectual output of the student mentioned below unless otherwise mentioned. Information given within this Design Dissertation is true to the best knowledge of the student mentioned below. All possible efforts have been made by the author to acknowledge the secondary sources information. Right to further modification and /or publication of this Design Dissertation in any form belongs to its author. Contents within this Design Dissertation can be reproduced with due acknowledgement for academic purposes only without written consent from the author. -

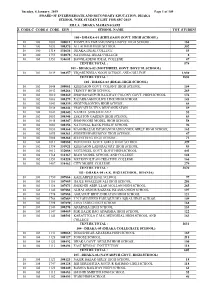

Crystal Reports

Wednesday, 2 January, 2019 Page 1 of 98 BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA LIST OF SCHOOL FOR SSC-2019 ZILLA : DHAKA MAHANAGARI Z_CODE C_CODE S_CODE EIIN SCHOOL NAME 100 - DHAKA-01 (KHILGAON GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL) 10100 1000 108012 RAMPURA EKRAMUNNESA BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 10 100 1030 108375 ALI AHMED HIGH SCHOOL 10 100 1318 131634 DHAKA IDEAL COLLEGE 10100 1356 134601 BANGLADESH IDEAL COLLEGE 10 100 1753 132078 NATIONAL IDEAL COLLEGE 101 - DHAKA-02 (MOTIJHEEL GOVT. BOYS' H. SCHOOL) 10 101 1039 108357 VIQARUNNISA NOON SCHOOL AND COLLEGE 10 101 1309 130864 ROYAL ACADEMY 102 - DHAKA-03 (IDEAL HIGH SCHOOL) 10 102 1002 108356 NATIONAL BANK PUBLIC SCHOOL 10 102 1004 108366 SHANTIBAG HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1006 108279 RAJARBAGH POLICE LINE HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1010 108269 SHAHJAHANPUR RAILWAY COLONY GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL 10102 1012 132088 MOTIJHEEL GOVT. BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1013 108580 MOTIJHEEL GOVT. GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1033 108360 MAGHBAZAR ISPAHANI MADHAYMIK GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1036 108344 PROVATI UCHYA BIDYANIKATON 10102 1040 108270 LUTFA ACADEMY 10 102 1041 108345 NAZRUL SHIKSHALAYA 10 102 1042 108266 TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1043 108339 SEGUNBAGICHA HIGH SCHOOL 10102 1045 108347 SHAHNOORI MODEL HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1048 108061 KHILGAON GOVT. COLONY HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1053 108346 ESKATON GARDEN HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1055 108361 SIDDHESWARI BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 10102 1359 134220 METROPOLITAN CREATIVE COLLEGE 10 102 1398 130921 KHILGAON LABORATORY HIGH SCHOOL 10 102 1407 134462 CITY MODEL COLLEGE 10 102 1764 132367 BIAM MODEL SCHOOL AND COLLEGE 103 - DHAKA-04 (A.K. -

Crystal Reports

Tuesday, 8 January, 2019 Page 1 of 109 BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, DHAKA SCHOOL WISE STUDENT LIST FOR SSC-2019 ZILLA : DHAKA MAHANAGARI Z_CODE C_CODE S_CODE EIIN SCHOOL NAME TOT. STUDENT 100 - DHAKA-01 (KHILGAON GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL) 10 100 1000 108012 RAMPURA EKRAMUNNESA BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 168 10 100 1030 108375 ALI AHMED HIGH SCHOOL 302 10100 1318 131634 DHAKA IDEAL COLLEGE 53 10 100 1753 132078 NATIONAL IDEAL COLLEGE 8 10 100 1356 134601 BANGLADESH IDEAL COLLEGE 47 CENTRE TOTAL : 578 101 - DHAKA-02 (MOTIJHEEL GOVT. BOYS' H. SCHOOL) 10 101 1039 108357 VIQARUNNISA NOON SCHOOL AND COLLEGE 1,830 CENTRE TOTAL : 1830 102 - DHAKA-03 (IDEAL HIGH SCHOOL) 10 102 1048 108061 KHILGAON GOVT. COLONY HIGH SCHOOL 154 10 102 1042 108266 TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL 269 10102 1010 108269 SHAHJAHANPUR RAILWAY COLONY GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL 176 10 102 1006 108279 RAJARBAGH POLICE LINE HIGH SCHOOL 143 10 102 1043 108339 SEGUNBAGICHA HIGH SCHOOL 64 10 102 1036 108344 PROVATI UCHYA BIDYANIKATON 39 10 102 1041 108345 NAZRUL SHIKSHALAYA 55 10 102 1053 108346 ESKATON GARDEN HIGH SCHOOL 63 10 102 1045 108347 SHAHNOORI MODEL HIGH SCHOOL 58 10 102 1002 108356 NATIONAL BANK PUBLIC SCHOOL 96 10102 1033 108360 MAGHBAZAR ISPAHANI MADHAYMIK GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL 162 10 102 1055 108361 SIDDHESWARI BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 47 10 102 1004 108366 SHANTIBAG HIGH SCHOOL 72 10 102 1013 108580 MOTIJHEEL GOVT. GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL 399 10102 1398 130921 KHILGAON LABORATORY HIGH SCHOOL 83 10 102 1012 132088 MOTIJHEEL GOVT. BOYS' HIGH SCHOOL 403 10 102 1764 132367 BIAM MODEL SCHOOL AND COLLEGE 142 10 102 1359 134220 METROPOLITAN CREATIVE COLLEGE 166 10102 1407 134462 CITY MODEL COLLEGE 279 CENTRE TOTAL : 2870 103 - DHAKA-04 (A.K. -

For More Information About Education in Bangladesh Log on To

For more Information About Education in Bangladesh log on to www.studyinbd.com DHAKA ADABOR 1082 BEGUM NURJAHAN MEMORIAL GIRLS H\S 40 DHAKA ADABOR 1084 KONDA HIGH SCHOOL 22 DHAKA ADABOR 1082 NABADIGANTA ADARARSHA BIDDALLYA 29 DHAKA ADABOR 1085 POST OFFICE HIGH SCHOOL,ADABOR 77 DHAKA ADABOR 1308 SHYAMOLY PUBLIC SCHOOL 66 DHAKA BADDA 1080 ABDUL KHALEQUE MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL 15 DHAKA BADDA 1080 ANANDA NAGAR ADARSHA VIDYALAY 22 DHAKA BADDA 1078 BADDA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 25 DHAKA BADDA 1078 BADDA HIGH SCHOOL 22 DHAKA BADDA 1078 BERAID MUSLIM HIGH SCHOOL 26 DHAKA BADDA 1080 KHIL BARIRTEK ISLAMIA HIGH SCHOOL 17 DHAKA BADDA 1309 LITTLE JEWELLS HIGHN SCHOOL 05 DHAKA BADDA 1309 NATIONAL SCHOOL 02 DHAKA BADDA 1078 ROWSHAN ARA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 21 DHAKA BADDA 1080 SATARKUL HIGH SCHOOL 21 DHAKA BADDA 1080 SOLMAID HIGH SCHOOL 13 DHAKA BADDA 1082 TRINTY HIGH SCHOOL 66 DHAKA CANTONMENT 1078 ADMJEE CANTONMENT PUBLIC SCHOOL 43 DHAKA CANTONMENT 1078 SHAHEED ROMIZ UDDIN CANTONMENT SCHOOL 50 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1078 ADRSHA BIDYA NIKETON 49 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1085 DAKSHIN KHAN ADARSHA GIRL'S HIGH SCHOOL 49 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1085 EMARAT HOSSAIN ADARSHA HIGH SCHOOL 45 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1085 GAWAIR ADARSHA HIGH SCHOOL 51 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1315 UTTARA MODEL SCHOOL 24 DHAKA DAKSHINKHAN 1078 UTTARA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 45 DHAKA DEMRA 1078 ALHAJ ABDUR RAZZAK ISLAMIA HIGH SCHOOL 84 DHAKA DEMRA 1078 BAWANY ADARSHA UCHCH BIDDYALAYA 65 DHAKA DEMRA 1078 BAWANY HIGH SCHOOL 67 DHAKA DEMRA 1078 DHITPUR HAZI MD. LAL MIA HIGH SCHOOL 62 DHAKA DEMRA 1078 DOGAIR MODEL HIGH SCHOOL 70 DHAKA -

Bangladesh Beckons 2019

BANGLADESH 2019 EDITION BECKONS The Art of Bangladesh: Embodiment of Social and Political Changes Social and Economic Progress of Bangladesh Bangladesh: An Ideal Destination for Foreign Investment Doing Business in Bangladesh: An overview Going Digital: Realizing the Dreams of a Digital Bangladesh for All Bangladesh: A Fascinating Tourism Destination A COMMEMORATIVE PUBLICATION BY THE HIGH COMMISSION OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH, SINGAPORE CONTENTS 2019 EDITION 1 Message from Hon’ble President 33 Opportunities of Investment in Power and Energy Sector in Bangladesh 2 Message from Hon’ble Prime Minister 39 Opportunities of Investment in Leather 3 Message from Hon’ble Foreign Minister Industry of Bangladesh 4 Message from Hon’ble 42 Going Digital: Realizing the Dreams of State Minister for Foreign Affairs a Digital Bangladesh for All 5 Bangladesh-Singapore Relations: 47 The Art of Bangladesh: Embodiment of Prospects and Priorities Social and Political Changes 9 Economic and Social Progress of Bangladesh 51 Bangladesh – A Fascinating Tourism Destination 14 Rohingyas in Bangladesh: The Crisis in Numbers 55 Activites of the High Commission in Pictures 19 Bangladesh: An Ideal Destination for Foreign Investment 27 Doing Business in Bangladesh: An overview Chief Patron Members Articles and Photo Cover His Excellency Khaja Miah Sabbir Ahmed Contribution Painting of Artist Md. Mustafizur Rahman Samia Halim Md. Rafiqul Islam High Commission Shahabuddin Ahmed A.K.M. Azam Chowdhury Morioum Begum Sworna of People's Editor Mohammad Ataur Rahman Republic of Bangladesh Md Faruk Hossain PROPERTY OF HIGH COMMISSION OF THE PEOPLE'S OF BANGLADESH #04-00/#10-00, Jit Poh Building, 19 Keppel Road Singapore 089058 Tel (65) 6255 0075 Fax (65) 6255 1824 URL www.bdhc.sg This publication has been prepared by the High Commission of the People's Republic of Bangladesh in Singapore commemorating the 48th Anniversary of Independence and National Day. -

Gvbca: Celebrating and Incorporating Bengali Culture in Multicultural Canada

SANZIDA HABIB AND HAFIZUL ISLAM GVBCA: CELEBRATING AND INCORPORATING BENGALI CULTURE IN MULTICULTURAL CANADA 1. INTRODUCTION Bangladeshi Bengalis carry their love and pride for their cultural heritage and linguistic and religious identities wherever they travel or migrate. No matter where they settle, most of them generally want and try to build a home away from home by practicing and preserving their rich national heritage and cultural legacies. The Bangladeshi Canadians in Greater Vancouver are no exception, and that is why there is a GVBCA – Greater Vancouver Bangladesh Cultural Association. The total number of Bangladeshi Bengalis living in Greater Vancouver is hard to ascertain, but a large number of them come together to socialize, celebrate Bengali culture, and observe important national days and events of Bangladesh organized by GVBCA. We, the President and Secretary of GVBCA, will outline a historical overview of this organization along with its main mandates, milestones and achievements. The mission, significance and contribution of this organization have been assessed and narrated in the relative contexts of the missions and activities of other important Bangladeshi/Bengali organizations. Additionally, some of the major challenges of the Association have been discussed alongside the broader vision and future prospects of this organization. There has been little official documentation of the history and activities of this organization, and this is likely the first ever comprehensive documentation and presentation related to GVBCA delivered at an academic conference. The information presented in this paper is derived from the constitution and contents found on the website of GVBCA. It is also based on the first author’s personal observation and insider experience credited to her involvement in the organization as a current Executive Committee member, and her role as a community member, activist, organizer and performer for almost 10 years. -

SPL Newsletter 2012 -.::Scholastica

Final Term 2011 - 2012 Message from the Chairman and Managing Director Dear Parents, Students, Faculty and Management, We are at the end of another school year, one marked with many achievements. Not only have our students (and faculty) distinguished themselves with all kinds of academic glories, but we have also maintained our reputation as a formidable force in Bangaldeshi youth sports and arts. At the same time, our students and faculty have ventured out into the world to build bridges and gain exposure in the international community. In the past year, we have worked hard to further strengthen and develop our facilities and academics in many ways, including: We have introduced the DigiClass system in our senior section and will be expanding it to the middle schools next year. We started working on installing air-conditioners in all the classrooms of the school, which will be functional from September. We launched a swimming program in our Mirpur campus, that is open to all students from Class III onwards, including a program to teach beginners how to swim. We have introduced a new Maths workbook in the junior school, and completed the development of two new Kindergarten English workbooks and a Bangladesh Studies book for Class III and IV which will be launched next year. A foreign consultant helped us to design and pilot a skills lab program in the middle school, which will be expanded in the Middle Uttara and Mirpur campus next year, addressing the special needs of students in English and Maths. We inaugurated the use of the STM Hall in the Mirpur campus, and are working on completing the construction of the Mirpur campus and all its facilities over the summer. -

![Atanu Sasmal [M.A., Ph.D] Associate Professor Department: Bengali Bhasha-Bhavana Visva-Bharati](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5243/atanu-sasmal-m-a-ph-d-associate-professor-department-bengali-bhasha-bhavana-visva-bharati-4625243.webp)

Atanu Sasmal [M.A., Ph.D] Associate Professor Department: Bengali Bhasha-Bhavana Visva-Bharati

Atanu Sasmal [M.A., Ph.D] Associate Professor Department: Bengali Bhasha-Bhavana Visva-Bharati Date of Birth: 10/10/1960 Date of joining VB: 01/02/2013(Visva-Bharati) Academic qualification: B.A(Hons)., Visva-Bharati, 1982 M.A. , Visva-Bharati, 1984 Ph.D, Visva-Bharati, 1996 Areas of Specialization: Bengali Short Story & Novel. Position and Employment Sl No. Institution Position From Date -To Date 1 Visva-Bharati Associate Professor 01.02.2013- Continuing 2 Abhedananda Mahavidyalaya Associate Professor 01.01.2006-31.01.2013 3 Abhedananda Mahavidyalaya Reader 01.04.1999-31.12.2005 4 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya Reader 27.07.1998-31.03.1999 5 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya Lecturer (Senior Scale) 29.01.1996-26.07.1998 6 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya Lecturer 29.01.1988-28.01.1996 7 Egra Sarada- Shashibhusan College Lecturer 02.03.1987-16.11.1987 Awards: Santoshchandra Smriti Puraskar Number of students awarded Ph.D.: 6 Number of students register for Ph.D.: 6 Publications: Non-Fiction or Research Work Books: 6, Fiction works: 3, Edited Books: 3, Articles in Books: 3, Articles in Journals: 15, Conference/ Seminar/Workshop: 25. Books: A. Non-Fiction or Research Work 1. Charya Chaitanyasatya O Rabindranath, Saptarshi Prakashan, 9 May 2007, Kolkata. (A collection of six critical essays: Charyapad, Chaitanya and regarding Rabindranath) 2. Ramanyee Panditer Sri Dharmapujabidhan o ekti Dhaner pala, Saptarshi Prakashan, 24 July 2007, Kolkata. (Rituals of worshiping Lord Dharma prescribed at Ramanyee Pandit’s manuscript and narrative of a paddy) 3. Rabindranathke Niye,(ISBN: 9789382706137), Saptarshi Prakashan, Kolkata-09, February 2013. (Regarding Rabindranath: Ten essays) 4. -

List of School

List of School Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100003 DAKSHIN KATHALIA TAZEM ALI SECONDARY SCHOOL KATHALIA 01720343613 2 100009 LOCHA JUUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL LOCHA 01553487462 3 100011 AMTALI A.K. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL 437, A K SCHOOL ROAD, 01716296310 AMTALI 4 100012 CHOTONILGONG HIGH SCHOOL CHOTONILGONG 01718925197 5 100014 SHAKHRIA HIGH SCHOOL SHAKHARIA 01712040882 6 100015 GULSHA KHALIISHAQUE HIGH SCHOOL GULISHAKHALI 01716080742 7 100016 CHARAKGACHIA SECONDARY SCHOOL CHARAKGACHIA 01734083480 8 100017 EAST CHILA RAHMANIA HIGH SCHOOL PURBA CHILA 01716203073,0119027693 5 9 100018 TARIKATA SECONDARY SCHOOL TARIKATA 01714588243 10 100019 CHILA HASHEM BISWAS HIGH SCHOOL CHILA 01715952046 11 100020 CHALAVANGA HIGH SCHOOL PRO CHALAVANGA 01726175459 12 100021 CHUNAKHALI HIGH SCHOOL CHUNAKHALI 01716030833 13 100022 MAFIZ UDDIN GIRLS PILOT HIGH SCHOOL UPZILA ROAD 01718101316 14 100023 GOZ-KHALI(MLT) HIGH SCHOOL GOZKHALI 01720485877 15 100024 KAUNIA IBRAHIM ACADEMY KAUNIA 01721810903 16 100026 ARPAN GASHIA HIGH SCHOOL ARPAN GASHIA 01724183205 17 100028 SHAHEED SOHRAWARDI SECONDARY SCHOOL KUKUA 01719765468 18 100029 KALIBARI JR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KALIBARI 0172784950 19 100030 HALDIA GRUDAL BANGO BANDU HIGH SCHOOL HALDIA 01715886917 20 100031 KUKUA ADARSHA HIGH SCHOOL KUKUA 01713647486 21 100032 GAZIPUR BANDAIR HIGH SCHOOL GAZIPUR BANDAIR 01712659808 22 100033 SOUTH RAOGHA NUR AL AMIN Secondary SCHOOL SOUTH RAOGHA 01719938577 23 100034 KHEKUANI HIGH SCHOOL KHEKUANI 01737227025 24 100035 KEWABUNIA SECONDARY -

CHAPTER 5 the INERTIA of NAZROL's LITERARY WORKS To

CHAPTER 5 THE INERTIA OF NAZROL'S LITERARY WORKS To define the overall characteristics of Kazi Nazrul Islam's works we need to focus on his personal life. Nazrul was a person who had experienced the World War II by getting involved in the war personally as a solder, observed and faced falism, religious riots, and human miseries all around. It is also to be cited that Nazrul, being born in a Muslim family lived a life of inconsistency, but he always remained as a preacher of human salvation by setting himself apart from all dogmatic and orthodoxical, paradoxical dilemmas. For he was a heterodoxical a person. o As a reversatile person he expressed his angustia anger, joy, sorrow and love vigorously through his poetry. In one of the most popular poems titled as "Bidrohi" (the rebell), he considers himself as the “Lord of the Lords,” “a torpedo," ”Bhima“ or "the wonder of the cosmos” by piercing all the spheres he places himself at the top most post of the universe, or in other words he elevates his human position by breaking the established notions and relationals of the ‘then’ society up to a suprime place. Here he announces the glory of human capability. On the contrary, in one another poem written, much later* which was later transformed in a form of song - he expresses a 394 sort of pare of eternal feeling; "God is my Lord, I have no fear, Quran is my Philosophy; Islam my identity.” Considering these two major opposite expressions are quite > « contradictory at one gliraps but it is to be noticed here that he realised the limitations of human being. -

Migration of Bengalis CANADA

CANADA 150 CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Migration of Bengalis HABIBA ZAMAN SANZIDA HABIB Editors Canada 150 Conference Proceedings: Migration of Bengalis Edited by HABIBA ZAMAN Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada and SANZIDA HABIB Research Associate, Center for India and South Asia Research University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada Copyright ©2018 Habiba Zaman & Sanzida Habib Vancouver BC Canada Cover Design: Sanzida Habib Printed and bound in Canada by SFU Document Solutions CONTENTS Contributors .......................................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................................... ix Introduction: Canada 150 Conference on Migration of Bengalis ....................................................... 1 HABIBA ZAMAN AND SANZIDA HABIB Opening Remarks ............................................................................................................................................... 11 JANE PULKINGHAM “Are You a Bengali or Are You an Indian?” Bengalis in Canada ....................................................... 15 TANIA DAS GUPTA Migration of Bengalis to Canada: An Historical Account .................................................................... 31 BIDISHA RAY An Oral History of Bengali Immigrants in British Columbia: -

Mihirkanti Choudhury 42 Ahsan Manjil, Tantipara ⚫ Sylhet City ⚫ Cell Phone: 01711 885068; 01771561175 ⚫ Email : [email protected] ⚫ [email protected]

Mihirkanti Choudhury 42 Ahsan Manjil, Tantipara ⚫ Sylhet City ⚫ Cell Phone: 01711 885068; 01771561175 ⚫ ⚫ Email : [email protected] [email protected] PERSONAL INFORMATION PHOTOGRAPH • OFFICIAL NAME MIHIR KANTI CHOUDHURY • PEN NAME MIHIRKANTI CHOUDHURY • LANGUAGE EFFICIENCY ENGLISH, BENGALI • NATIONALITY BANGLADESHI EDUCATION • B.A. (HONOURS) IN ECONOMICS, GAUHATI UNIVERSITY (INDIA), 1979, 2ND CLASS. • MBA (HRM), METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY, SYLHET (BANGLADESH), 2014, CGPA 3.99 (4.00). • TKT (MAJOR TRAINING IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE), CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY, BAND 3. PRESENT POSITIONS • Deputy Registrar, Metropolitan University, Sylhet. • Adjunct Faculty, Department of Business Administration, EEE and CSE, Metropolitan University, Sylhet. • Principal, Mihir Academy, SYLHET (an online Centre for English Language Studies). • Chief Executive, TAGORE CENTRE, SYLHET (a research centre for Literary Studies). PAST POSITIONS • Principal of ACADEMY OF TWO R’S (a school of language and literature). Continuation now in Mihir Academy. • Teacher Trainer, UKBET (UK Education Trust). • Interlocutor, CITY AND GUILDS, UK FOR ESOL Programme. • Freelance Education Consultant AREAS OF INTEREST • English Language and • Diplomatic Studies Literature • International Relations • Bengali Literature (Tagore) • Cultural Studies • Political Studies • Folklore AREAS OF REFLECTION • English Language • Reviewer (Bilingual) • Writer (Bilingual, Eng. Beng.) • Editor (Bilingual) • Researcher • Writer of catalogs, course guides and • Translator (Bilingual) training brochures • Proof Reader (Bilingual) Mihirkanti Choudhury • Cell Phone: 01711 885068; 01771561175 2nd page • [email protected]; [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE • Deputy Registrar in Metropolitan University, Sylhet from January 01, 2015 Till Date. • Director (Finance), Metropolitan University, Sylhet from 1st September, 2015 to 31st December 2018 (Additional Responsibility). • Teaching in Metropolitan University, Sylhet as Adjunct Faculty in the Departments of Business Administration, EEE and CSE from January 01, 2015.