Public Art 1945-95 Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

Freud on Time and Timelessness: the Ancient Greek Influence

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Freud on time and timelessness: the ancient Greek influence https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40071/ Version: Full Version Citation: Noel-Smith, Kelly Ann (2014) Freud on time and timelessness: the ancient Greek influence. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Freud on Time and Timelessness: the Ancient Greek Influence A dissertation presented by Kelly Ann Noel-Smith in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Birkbeck College, University of London January 2014 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. …………………………………………………… ………………… 2014 Kelly Ann Noel-Smith © 2014 Kelly Noel-Smith. All rights reserved. 2 Kelly Noel-Smith Freud on Time and Timelessness: the Ancient Greek Influence Abstract This thesis turns on two assumptions: first, that there is a current absence within the psychoanalytic library of a consolidated account of Freud's theories of time and timelessness; second, that there is compelling evidence of an influence by the ancient Greek canon on Freud's metapsychology of time. The thesis is that a detailed examination of this influence will bring additional clarity to our understanding of Freud’s thoughts about time and timelessness and permit the provision of the currently lacking systematic account of this part of his theory. The author brings the three components of the Greek canon most important to Freud - myth, tragedy and philosophy – into dialogue with psychoanalysis to show the importance of their influence on Freud's ideas on temporality. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

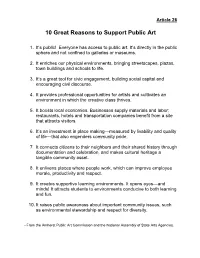

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

Donald Gibson and Coventry

Original citation: Campbell, Louise (2007) Paper dream city/modern monument : Donald Gibson and Coventry. In: Boyd Whyte, Iain, (ed.) Man-made future : planning, education and design in mid-twentieth-century Britain. London ; New York: Routledge, pp. 121-144. ISBN 9780415357883. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/53223 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Man-made future : planning, education and design in mid-twentieth-century Britain on 2007, available online: http://www.routledge.com/Man-Made-Future-Planning-Education-and-Design-in- Mid-20th-Century-Britain/Whyte/p/book/9780415357883 A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. -

Public Art Policy

CITY OF GILROY PUBLIC ART POLICY VISION STATEMENT: The City of Gilroy’s Public Art Committee promotes a bold vision which exemplifies the City’s creativity and energy shaping the visual environment of our community. PURPOSE: The City of Gilroy (City) recognizes the importance of Public Art to the cultural, educational and economic well-being of its diverse population. These guidelines are for the purpose of establishing policies and procedures for implementing Public Art as recommended in the Arts & Culture Commission’s Cultural Plan, developed in 1997, and 1999 General Plan Update. GOALS: To promote the City’s interest in its aesthetic environment. To establish the Public Art Committee as an advisory committee to the Arts and Culture Commission to be responsible for developing the Public Art Plan; ensuring the quality of artworks created under the plan; and, developing budgets, funding strategies and scope of individual Public Art projects. To create an enhanced visual environment within the City and provide City residents with the opportunity to live with Public Art. To help build pride in our City and among its citizens. To promote tourism and economic vitality of the City by enhancing the City’s public facilities and surroundings through the incorporation of Public Art. To encourage creative collaboration among community members. To encourage the creation of quality Public Art throughout the City by promoting locally, regionally, nationally and internationally recognized artists. To educate, preserve, reflect and celebrate the rich, unique history and cultural diversity of the City and its citizens. To promote and encourage art viewed by the public in all of the City’s communities and neighborhoods and to support the residents’ involvement in determining the character of their City. -

The Festival of Britain 1951

BANK OF ENGLAND ISSUED BY THE COURT OF DIRECTORS ON THE OCCASION OF THE FESTIVAL OF BRITAIN 1951 Bank of England Archive (E6/8) The Bank of England completed III I939 to the design of Sir Herbert Baker Bank of England Archive (E6/8) [Copyright BUII/� 0/ Ellglalld HE BANK OF ENGLAND came into being to provide funds for the T war that was being fought between 1689 and 1697 by William III against Louis XIV of France. In return for a loan of £1,200,000 to the King the subscribers, who numbered 1,272, were granted a Royal Charter on the 27th July, 1694, under the title " The Governor and Company of the Bank of England ". The Bank of England Act of I 946 brought the Bank into public ownership, of the but provided for the continued existence of the " Governor and Company ; Bank of England " under Royal Charter. The affairs of the Bank are administered by the Court of Directors, appointed by the King and comprising a Governor and Deputy Governor, each appointed for five years, and 16 Directors, each appointed for four years. The Court may appoint four of their members as Executive· . Directors, who, together with the senior officials and a number of specialists as advisers, assist the Governors in the day-ta-day management of the Bank. Over the years the Bank of England has become the " bankers' bank ". and banker to the Government. The description " bankers' bank" indicates that the principal banks in the United Kingdom deposit with it their reserves of cash. -

8. Festival Guide

8. Festival Guide Dr Harriet Atkinson is a leading historian of design and culture based at the University of Brighton. She is one of the foremost experts on the Festival of Britain. In this response she brings her extraordinary knowledge of this event to bear on a commonplace piece of Festival ephemera. In doing so she reveals powerful themes of patriotism, land, refugees, and a whole series of intersections between design and identity that feel as relevant today as they did seven decades ago. Ian Cox, The South Bank Exhibition: A Guide to the Story It Tells (London: HMSO, 1951) As memories of a day out at the Festival of Britain’s South Bank Exhibition faded, the guidebook was often the only thing that remained. A substantial, handsome book printed on luxuriously thick paper, it bore designer Abram Games’s Festival of Britain emblem, Britannia in profile, on the front cover. She was festooned with bunting and mounted on the four points of the compass indicating the nationwide reach of the events, all in the patriotic colours of the Union Jack. Cover of the Exhibition Guide featuring the Abram Games festival logo (MERL Library 1770-COX) What was this ‘magical city’, as one designer described the Festival’s London centrepiece, the South Bank Exhibition held from May to September 1951, this temporary world that so enchanted and amazed its visitors? And what kind of Britain do we encounter as we turn the Guide’s mustard cover seventy years on? 1 While advertising was banned at the South Bank Exhibition itself, here, in the Guide, was the chance to sell things to the Festival’s many visitors. -

Museum of London Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31St March 2012

Registered Charity No: 1139250 MUSEUM OF LONDON Governors’ Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2012 Museum of London Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31st March 2012 CONTENTS Reference and administrative details 2 - 4 Annual Report 5 – 23 Independent Auditors’ Report 24 – 25 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 26 Consolidated Balance Sheet 27 Museum of London Balance Sheet 28 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 29 - 30 Notes to the Financial Statements 31 - 52 1 Museum of London Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31st March 2012 REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS Name Museum of London Address 150 London Wall London EC2Y 5HN Board of Governors A Board of Governors, consisting of 18 members of whom the Greater London Authority (GLA) (prior to April 2008: the Prime Minister) and the City of London Corporation (COL), each appoints 9 members, is responsible for the general management and control of the Museum. The following Governors served throughout the financial year, except where indicated. Appointed by the Kenneth Ayers (ceased to be a Trustee 22 March 2012) City of London Rt Hon the Lord Boateng P.C. D.L. Corporation Sir Steve Bullock (appointed 20 April 2011) Michael Cassidy CBE Rev Dr Martin Dudley Robert Dufton Tom Hoffman Julian H Malins QC John Scott (appointed 21 June 2012) Michael Welbank Appointed by the GLA Jennette Arnold (prior to April 2008 : by the Blondel Cluff Prime Minister) Rosemary Ewles Gillian Day (appointed 5 October 2011) Andrew Macdonald Camilla Mash Mark Palmer-Edgecumbe Eric Reynolds Eric Sorensen Administration Under the Museum of London Acts 1965 and 1986, the Board is required to appoint a Director of the Museum to be responsible to the Board for: .