FSX Xtreme Prototypes CF-105 Arrow Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Comox Air Force Museum's Guide to the Aircraft of the Heritage Air Park

The Comox Air Force Museum’s Guide to the Aircraft of the Heritage Air Park By Dan Brennan *All photographs found in this guide are subject to copyright and cannot be reused without the express written permission of the owner. Canadair CL-28 Argus Mark I Argus 10719 of 415 Squadron on maritime patrol. From Greek mythology, the “Argus” was an all-seeing creature with 100 eyes. This name was appropriate due to the numerous highly sophisticated sensing devices carried on board, with antennas everywhere. Note the large nose radome of the Mark I. Protruding from the tail is the MAD Boom, a Magnetic Anomaly Detector which detects the magnetic field surrounding a steel submarine. The Canadian-built, Canadair Argus was a unique hybrid that employed the wings, tail surfaces and undercarriage of the British designed Bristol Britannia transport aircraft, married to a completely new unpressurized fuselage of Canadian design and equipped with different American-designed engines. One of the most effective anti-submarine warfare aircraft of its day, the Argus was a mainstay for the RCAF in the maritime role. The principal difference between the Mark I and Mark II was primarily in the different navigation, communication and tactical electronic equipment fitted internally. Externally, the Mark II exhibited a redesigned smaller nose radome and additional ECM antennae above the fuselage. The Argus replaced the Lancaster and Neptune aircraft types and eventually, the Argus was itself to be replaced by the current Lockheed CP-140 Aurora aircraft. The Argus flew with the Maritime Proving & Evaluation Unit and the following Squadrons: 404, 405, 407, 415, and 449. -

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT STANLEY H. COHN INTERVIEWED BY SUMMER CHICK BERGEN OAKVILLE, ONTARIO, CANADA – 19 OCTOBER 1998 BERGEN: This is an oral history interview with Stanley Cohn in Oakville, Ontario, Canada, on October 19, 1998. This oral history is being conducted by Summer Chick Bergen, assisted by Carol Butler, for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Why don't we begin with you telling us about your educational background. COHN: All right. I'd just like to say I'm very pleased to be invited to participate in this project. It's nice to bring up old memories. My education has been mainly in mathematics and physics at the University of Toronto. I received a bachelor's degree in 1948. Then I did some further graduate work in mathematics at Indiana University in Bloomington, and completed course work requirements towards a Ph.D. degree, but I had a number of distractions that prevented me from completing that. As a matter of fact, it was at that time I was a graduate student at Indiana, that I first became exposed to computers in their primitive, primitive form. That would have been about 1951. I obtained a part-time job as a research mathematician there on an Air Force- sponsored project relating to scattering of light from suspended particles, such as fog. It involved quite complex mathematical functions and calculations to get the intensity of the light scattered. So they had installed a small primitive IBM [International Business Machines] machine, it was called the IBM 602A punch-card calculator. You programmed it by plugging wires into a plug board and each program then consisted of a removable plug board that was inserted into the machine. -

News & Notes: Vol. 32, No. 4, Fourth Quarter 2015

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Volume 32, Number 4 Fourth Quarter 2015 FROM A RECOLLECTION OF GEMINI FROM THE CHIEF 40 FEET AND 20 KNOTS HISTORIAN By William R. Carpentier, M.D., with John B. Charles, Ph.D. e are in the Wmiddle of the n January 1965, through a combina- 50th anniversary year Ition of preparation and luck, I joined IN THIS ISSUE: of Project Gemini. NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center From the spring of (now Johnson Space Center) as a flight 1 From the Chief Historian 1965 through the end of 1966, 10 crewed surgeon trainee and was privileged to A Recollection of Gemini from Gemini missions successfully propelled the participate in a truly great adventure. In 1 United States from apparent perpetual also- July, I became a staff flight surgeon in the 40 Feet and 20 Knots ran to clear leader of the space race. But ask Medical Operations Office. I was soon 8 James A. Chamberlin and the most people about the space program in the assigned the job of flying in the recovery Birth of Gemini 1960s and you’ll hear about Apollo and, some- helicopter for the Gemini 5, 6, 7, and 9 times, the Mercury 7 astronauts. Gemini? missions, as well as working with the Navy 12 Francis Rogallo and the Hardly anybody remembers it, and fewer still Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) Development of Parawing Landing appreciate how it served as the critical test- swimmers in order to provide medical Craft for Project Gemini ing ground between our initial baby steps in support for astronaut rescue operations. -

Techtalk: Fleet Finch and Canuck

BRINGING BRITISH COLUMBIA’S AVIATION PAST INTO THE FUTURE CCAANNAADDIIAANN MMUUSSEEUUMM OOFF FFLLIIGGHHTT TTEECCHHTTAALLKK:: FFLLEEEETT FFIINNCCHH AANNDD CCAANNUUCCKK The Canadian Museum of Flight is presenting a series of informal technical talks on aircraft in its fleet. These talks will cover topics ranging from the history of the com - pany; the history of the aircraft type; and its development; production methods and places; the history of the engine and its development. Also covered will be the challenges in maintaining and flying these classic aircraft in today’s environment; how the mechanics find the parts and how the pilots keep current on flying a 70 year old flying machine designed before the dawn of the jet age. This will be followed by details of how the aircraft is prepared for flight; how the en - gine is started; followed by an engine start and flight. During the proceedings, a draw will be conducted entitling the lucky winner to a flight in the aircraft being discussed (some conditions apply). FLEET 16B FINCH FLEET 80 CANUCK 2 THE HISTORY OF THE FLEET FAMILY OF AIRCRAFT CORPORATE HISTORY Reuben Fleet was born on March 6, 1887, in Montesano, Washington. The Fleets were a prosperous family; his fa - ther was city engineer and county auditor for Montesano, and owned large tracts of land in the Washington Territory. Reuben grew up in Grays Harbor, Washington. At 15, Fleet attended Culver Military Academy where his uncle was su - perintendent. In 1907, Fleet returned home where he began teaching all grades from first through eighth. After a num - ber of months, Fleet set himself up as a realtor and resigned from teaching. -

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT JOHN F. YARDLEY INTERVIEWED BY SUMMER CHICK BERGEN ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI – 29 JUNE 1998 BERGEN: This is an interview with John F. Yardley on June 29, 1998, in St. Louis, Missouri, interviewed by Summer Chick Bergen for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Like I said, we're going to start at the beginning, and I'd like to start a long, long time ago when you were young and you were a child, because that was before the advent of the Space Age. When you were growing up, did you ever think that men would go into space? YARDLEY: Well, of course, I was in the age of Buck Rogers and some other guy doing that, too, so I never really seriously thought about it, but I was in love with airplanes at the time. I built a lot of model airplanes and decided through that activity to get prepared in high school for an aeronautical engineering course in college. BERGEN: And then you went and got your aeronautical engineering degree? YARDLEY: Well, it wasn't quite that simple. The war started, you know, and when I got out of high school I was only sixteen, so I didn't get drafted right away. But everybody had lost their jobs. My dad was trying to get another job, so we didn't have enough money to go off to Harvard or anything like that, but I was able to get a scholarship to Washington University here locally, but they didn't have aeronautical engineering. I took mechanical. -

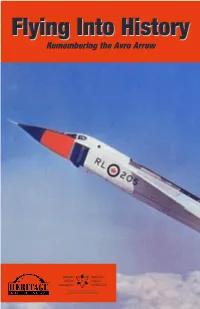

Remembering the Avro Arrow Overview

FlyingFlying IntoInto HistoryHistory Remembering the Avro Arrow Overview The Avro CF-105 Arrow“ ” was a delta-wing jet interceptor aircraft, designed and built by A.V. Roe Canada Limited in Malton as the culmination of a design study that began in 1953. Go-ahead on the production of the CF-105 was given in 1955, and the AVRO Arrow was rolled out for the public on October 4, 1957. The first test flight took place on March 25, 1958. TheArrow and the accompanying Orenda Iroquois jet engine program were abruptly cancelled by the Federal Government on February 20, 1959 (“Black Friday”), sparking a long and bitter social and political debate. At the time of its cancellation the Arrow was considered to be one of the most advanced aircrafts in the world. It was built, flown, and destroyed within the City of Mississauga. Front cover: AVRO Arrow RL-205 in flight, photo courtesy of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society Above: Celebrating the first flight of AVRO Arrow RL-201with chief test pilot Jan Zurakowski, photo courtesy of the Windsor Star 1 History The story of the Arrow began in 1952 when the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was looking to develop a new all-weather jet interceptor capable of extremely high levels of performance. The RCAF contracted A.V. Roe Canada (AVRO Canada), which was based in Malton, Ontario. Avro had already produced the CF-100 “Canuck”, Canada’s first all-weather jet interceptor. In 1953, research and design for the CF-105 supersonic, all-weather jet interceptor began, with formal production and testing starting in 1954. -

Specification AIR 7-3" in April 1953

CANADA AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUM AIRCRAFT AVRO CANADA CF-105 ARROW RCAF SERIAL 25206 (NOSE SECTION & COMPONENTS ONLY) Introduction The CF-105 Arrow was a delta-winged interceptor aircraft, designed and built by A.V. Roe (Avro) Canada as the culmination of a series of design studies that originally began in 1953. The Arrow is considered by many to have been one of the most advanced technological achievements by the Canadian aviation industry. The CF-105 design was capable of near-Mach 2 speeds at altitudes in excess of 15,250 meters (50,000 feet) and it was intended to serve as the Royal Canadian Air Force’s (RCAF) primary interceptor in the 1960s and beyond. However, in February 1959, in the midst of its flight test program, the development of the CF-105 Arrow (including all of its associated programs, such as the Orenda Iroquois jet engines, Astra fire control system and missile armament systems) was abruptly cancelled before a scheduled final project review had taken place, sparking an intense and often bitter political debate. The controversy engendered by this cancellation, and the subsequent destruction of all of aircraft then in production, still remains a topic for debate amongst historians, politicians, authors and aircraft enthusiasts. This decision not only resulted in the termination of the aircraft program but also led to the demise of Avro Canada. Background Prior to 1939, as “war clouds” loomed on the horizon, the Canadian government encouraged a number of "shadow factories" to be set up in order to produce British aircraft designs in relative safety. -

CHAPTER 5: Gemini: on Managing Spaceflight

CHAPTER 5: Gemini: On Managing Spaceflight “The first phase of the Nation’s second manned space program began like a story- book success” on Saturday, April 8, 1964, when an unmanned, partly instrumented Gemini capsule entered orbit from its launch site at Cape Canaveral. 1 The 12 Gemini flights complet- ed by mid-1966 brought America from the edge of space to outer space, from the pioneering days of Mercury to the lunar landings of Apollo, and into new management techniques including processes like systems and subsystems management, configuration control, and incentive contracting. A major building block in the operations components of spaceflight, Gemini provided an invaluable learning experience in flight control, rendezvous, docking, endurance, extravehicular activity, controlled reentry, and worldwide communications. But the acceleration of Gemini and Apollo programs strained the human resources of the Houston center and created stress and management crises. Although critical in the manned space effort, Gemini was much more and much less than a “storybook” success. The April 1964 launch of the first unmanned Gemini spacecraft on the shoulders of an Air Force Titan II rocket was followed in May with the launch of the first Apollo vehicle aboard a Saturn I. Both coincided nicely with the final relocation of Manned Spacecraft Center personnel to their new permanent site at Clear Lake. Director Bob Gilruth declared an “open house” for the weekend of June 6 and 7, and took great “personal and professional satisfaction” in welcoming the public to the NASA MSC. 2 It was an open house that has been extended throughout the days of the Johnson Space Center, helping establish the important precedent that the center and NASA flight missions are for participation in and viewing and use by the public. -

THE LEGENDARY LANCASTER C-GVRA, Or “Vera”, Is the Last Remaining Airworthy Canadian-Built Avro Lancaster, and One of Only Two Left Flying in the World

AN MHM PUBLISHING MAGAZINE // JUNE/JULY 2018 INDUSTRY LABOUR AIRSPRINT TRANSPORT AIRBUS H160 2018 DEMO HAMILTON SHORTAGE PROFILE CANADA ASD FLIGHT TEST HORNET AIRPORT PROFILE SKIES MAGAZINE SKIESMAG.COM June/July 2018 June/July 1 SKIES Magazine SKIES THE LEGENDARY LANC We visit the team that keeps her flying! FEATURE | Feature Title Introducing HondaJet Elite skiesmag.com Redefi ning the light jet class with superior performance 2 born from aerodynamic breakthroughs. With HondaJet Elite, Honda Aircraft Company designed an aircraft with the betterment of humankind in mind. The advanced innovations were created to improve lives and the world. SKIES Magazine SKIES That’s why the HondaJet Elite not only transports passengers further, faster and higher than any aircraft in its category, but also takes care of the planet while doing so. The HondaJet Elite is more than just a technologically advanced aircraft – it is the connection to people and the world around us. Learn more about the innovations at HondaJetElite.com. © Honda Aircraft Company 1.336.387.0707 • HondaJetElite.com Skies Introducing HondaJet Elite Redefi ning the light jet class with superior performance 2018 June/July born from aerodynamic breakthroughs. 3 With HondaJet Elite, Honda Aircraft Company designed an aircraft with the betterment of humankind in mind. The advanced innovations were created to improve lives and the world. That’s why the HondaJet Elite not only transports passengers further, faster and higher than Magazine SKIES any aircraft in its category, but also takes care of the planet while doing so. The HondaJet Elite is more than just a technologically advanced aircraft – it is the connection to people and the world around us. -

602 1927 Modified Version of Avenger. Span 32', Height 9'9” Engine Unspecified. Not Built. 603 1927 8 Passenger Monoplane

602 1927 Modified version of Avenger. Span 32’, Height 9’9” Engine unspecified. Not built. 603 1927 8 passenger monoplane to Australian Govt. spec’n. 3x A-S Lynx Not built. 604 1927 ANTELOPE. 2-seat high performance day bomber to Spec.12/26. 480hp R-R F.XIB. Span 36’/32’,Length 31’2”,Height 10’9”, AUW 4,550lb. Prototype only built, in competition with Fairey Fox & Hawker Hart. 605 1927 AVIAN III or IIIA.Type No. allocated to floatplane version. Length 25’,Height 9.5’,AUW 1,600lb. 605A 1927 Type 605 fitted with 100hp Avro Alpha. Not built. 605B 1927 Type 605 fitted with 80hp A-S Genet. Not built. 606 1927 Monoplane maritime patrol flying boat to Spec.4/27, with square-section hull.3x 505hp Bristol Jupiter VII. Span 110’ AUW 21,050lb Not built. 607 1927 As above with round-section hull. Span 96’4”,Length 66’9”, Height 20’ Not built. 608 1927 HAWK. 2-seat biplane fighter based on Type 604. 425hp Bristol Jupiter. Re-worked into Type 622 during construction. Span 36’/32’ AUW 5,150lb 609 1927 3-seat military seaplane based on Type 608. Not built. 610 1928 SALOON. 5-seat high wing cabin monoplane. A-S Lynx. Span 43.5’ AUW 3,140lb Not built. 611 1928 CIERVA C.8L Mk.I. autogiro based on Type 504N. Rotor dia. 39’8”, AUW 3,535lb 1 built 612 1928 CIERVA C.17 Mk.I. Autogiro based on Avian IIIA. 90hp ADC Cirrus III. Rotor dia.33’3”,Length 28’9”,Height 11’1”,AUW 1,455lb. -

CASM-Monograph-CF-100

CANADA AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUM AIRCRAFT AVRO CANADA CF-100 MARK 5D Introduction The Avro Canada CF-100 was an all weather fighter nicknamed the Canuck; compatriot Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) F-86 Sabre pilots good-naturedly called it the “Clunk” or the “Lead Sled” compared to their own lighter mounts. It was the first jet fighter completely designed and built in Canada. While Canada had manufactured over 16,000 aircraft for military needs before and during the Second World War, almost all were of British or American design and built under license. Due to Canada’s small population size and relatively small tax base, Canada was somewhat dependent upon foreign governments towards obtaining aircraft to meet Canadian requirements. The CF-100 was the earliest aircraft designed and built specifically for Canadian military needs during the turbulent Cold War era. This monograph describes several aspects of the Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck in four parts as follows: Part 1. CF–100 Design History and Development; Part 2. Aircraft Weapons and Systems; Part 3. CF–100 Operational Squadrons and Employment; and Part 4. The Museum Exhibit History.1 CF-100 serial number 100785, on the final flight of a Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Canuck, is seen over Ottawa just prior to touching down at the National Aviation Museum. (CF Photo REC82-926 via CASM) Cover Photo Caption: The National Aviation Museum’s Avro Canada CF-100 Mark (Mk) 5D Canucks, CAF serial numbers 100785 and 100757, both from No. 414 Black Knight Squadron, repose adjacent to the Museum. Aircraft ‘785 had been painted black in 1981 to commemorate the original CF-100 Mk 1 prototype for 414 Squadron’s CF-100 “Close-out” ceremonies. -

VFC's Fleet 80 Canuck CF-DQE Where Is It Now? January 2017

January 2017 THE PThe VictoriaATRICIAN Flying Club ~ Aviation Excellence Since 1946 VFC's Fleet 80 Canuck CF-DQE Where is it now? January 2017 TMonthlyHE Newsletter of PThe VictoriaATRICIAN Flying Club - Aviation Excellence Since 1946 “To promote flying and aviation in general, and to teach and train persons in the art and science of flying In This Issue and navigating and operating all manner of heavier-than-air aircraft.” 2 News Around the Club (Victoria Flying Club Incorporation Bylaws, 1946) 5 Social Media Picks BOARD OF DIRECTORS 6 The Little Pilot Shop PRESIDENT Ramona Reynolds 7 Fondness for a Fleet [email protected] Contributed by Robert Stitt VICE PRESIDENT Howard Peng SECRETARY Colin Williamson 11 Income Tax Forms TREASURER Vernon Fischer DIRECTORS Steve Demy 13 First Solos and Member Rob Shemilt Achievements Rolf Hopkinson John Litherland 15 PrepAIR Tower Talk GENERAL MANAGER Gerry Mants Contributed by Simon Dennis CHIEF FLYING Graham Palmer INSTRUCTOR 17 Fly-Out Bug 18 Ground School Schedule 1852 Canso Road Sidney, BC V8L 5V5 www.flyvfc.com [email protected] Phone: 250-656-2833 Editor: Katy Earl Front cover photo credits: Instagram: matthewhughson. [email protected] Autumn / winter flying over Salt Spring Island. The Patrician accepts unsolicited submissions. Connect with us and share your aviation stories! This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, with prior permission of the publisher or author. The opinions expressed are strictly those of the authors. VFC News News Around the Club NEW ARRIVALS before a delicious dinner and the club. That’s what makes the Wings awards ceremony.