Case Study of the Transportation Sector's Response to and Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\TEMP\Copy of HB136 Act (Rev 1).Wpd

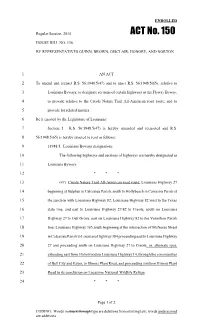

ENROLLED Regular Session, 2014 ACTÿNo.ÿ150 HOUSE BILL NO. 136 BY REPRESENTATIVES GUINN, BROWN, GISCLAIR, HONORE, AND NORTON 1 AN ACT 2 To amend and reenact R.S. 56:1948.5(47) and to enact R.S. 56:1948.5(65), relative to 3 Louisiana Byways; to designate sections of certain highways as the Flyway Byway; 4 to provide relative to the Creole Nature Trail All-American road route; and to 5 provide for related matters. 6 Be it enacted by the Legislature of Louisiana: 7 Section 1. R.S. 56:1948.5(47) is hereby amended and reenacted and R.S. 8 56:1948.5(65) is hereby enacted to read as follows: 9 §1948.5. Louisiana Byways designations 10 The following highways and sections of highways are hereby designated as 11 Louisiana Byways: 12 * * * 13 (47) Creole Nature Trail All-American road route: Louisiana Highway 27 14 beginning at Sulphur in Calcasieu Parish, south to Hollybeach in Cameron Parish at 15 the junction with Louisiana Highway 82; Louisiana Highway 82 west to the Texas 16 state line, and east to Louisiana Highway 27/82 to Creole, south on Louisiana 17 Highway 27 to Oak Grove, east on Louisiana Highway 82 to the Vermilion Parish 18 line; Louisiana Highway 385 south beginning at the intersection of McNeese Street 19 in Calcasieu Parish to Louisiana Highway 384 proceeding east to Louisiana Highway 20 27 and proceeding south on Louisiana Highway 27 to Creole; or, alternate spur, 21 extending east from Holmwood on Louisiana Highway 14, through the communities 22 of Bell City and Hayes, to Illinois Plant Road, and proceeding south on Illinois Plant 23 Road to its conclusion on Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge. -

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita – Louisiana's Response And

HURRICANES KATRINA AND RITA – LOUISIANA’S RESPONSE AND RECOVERY Ray A. Mumphrey, P.E., Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Hossein Ghara, P.E., MBA, Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development, Baton Rouge, Louisiana KEYWORDS: Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Contra flow, Inundation, Fixed and Movable Bridges, Open Water Bridges, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority ABSTRACT: Louisiana’s transportation and hurricane protection system took a tremendous blow from two major hurricanes that struck the coast of Louisiana in 2005, hurricanes Katrina and Rita. This presentation will introduce the audience to the transportation infrastructure damage Louisiana experienced as a result of these two storms and will describe how Louisiana is responding to the disasters and our road to recovery. Figure 1 - Hurricanes that hit the coast of Louisiana since 1900 As Louisiana residents, we become accustom to the ever present threat of hurricanes. Refer to figure 1. Much like other parts of the country, which have other natural disasters such as tornados, mud slides, avalanches or earthquakes, we just prepare for the worst, minimize loss of life and property, and thank God when it’s all over. As engineers we know we can always rebuild structures, and possibly restore livelihoods, but loss of life is not replaceable. 2005 STORMS Hurricane Katrina was a category 4 storm when it made landfall on August 29, 2005, along the Louisiana – Mississippi Gulf Coast. The storm was fast moving and provided minimum time for preparation. Refer to figure 2. “Hurricane Katrina was the most destructive hurricane to ever strike the U.S.” NOAA Just as we were getting back on our feet from the impacts of Hurricane Katrina, BAM! We were faced with another storm, Rita. -

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 197 Friday, October 9,1970 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 35 • NUMBER 197 Friday, October 9,1970 • Washington, D.C. Pages 15889-15968 Agencies in this issue— The President Agency for International Development Agricultural Research Service Atomic Energy Commission Business and Defense Services Administration Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Coast Guard Commodity Credit Corporation Consumer and Marketing Service Customs Bureau Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Reserve System Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration Interim Compliance Panel (Coal Mine Health and Safety) Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Labor Standards Bureau Land Management Bureau Monetary Offices Public Health Service Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration State Department Veterans Administration Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Presidential Proclamations and Executive Orders 1936-1969 The full text of Presidential proclamations, Executive orders, reorganization plans, and other formal documents issued by the President and published in the Federal Register during the period March 14, 1936-December 31, 1969, is available in Com pilations to Title 3 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Tabular finding aids and subject indexes are included. The individual volumes are priced as follows: 1936-1938 Compilation—$6.00 1959-1963 Compilation—$6.00 1938-1943 Compilation—$9.00 1964-1965 Compilation—$3.75 1943-1948 Compilation—$7.00 1966 Compilation----------- $1.00 1949-1953 Compilation—$7.00 1967 Compilation----------- $1.00 1954-1958 Compilation—$4.00 1968 Compilation----------- $0.75 1969 Compilation- --------$1.00 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

The East Coast Tidal Surge of 5 December 2013 Lincolnshire

OFFICIAL Lincolnshire’s Tidal Surge Response & Recovery ‘After Action’ Report The East Coast Tidal Surge of 5th December 2013 Lincolnshire Resilience Forum’s Response & Recovery ‘After Action’ Report 20th March 2014 1 OFFICIAL Lincolnshire’s Tidal Surge Response & Recovery ‘After Action’ Report Foreword On Thursday 5th December 2013 a deepening pressure system combined with high astronomical tides and strong to gale force ‘north westerly’ winds to generate a coastal surge along the whole of the east coast of England, the largest surge since the ‘great storm’ of 1953. Due to advances in surge forecasting, flood prediction and contingency planning at national, sub-national and local levels we were able to ‘get ahead’ of the storm. From Tuesday 3rd December partners began deploying one of the largest multi-agency emergency response and recovery operations ever conducted in Lincolnshire. This included the most significant evacuation operation in recent memory, the rescue of a number of people who became isolated by floodwaters, and work to ensure critical services were maintained and damaged infrastructure quickly repaired. Thankfully there were only 3 (relatively minor) casualties as a result of the surge, but more than 720 residential and commercial properties were inundated from the resultant overtopping and breach of defences. I would like to pass on my sympathy and support to those whose households and businesses flooded. We continue to work to support a full community recovery, and I commend the work of colleagues at Boston Borough Council who have led this work. In the circumstances this was a very good, forecast-led response and recovery effort. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

Fort Proctor: a Conditional Preservation

Fort Proctor: A Conditional Preservation Ursula Emery McClure, Bradley Cantrell Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA ABSTRACT: The preservation and sustainability of building cultural heritage in indeterminate landscapes and sites at extreme environmental risk raises several questions regarding methodology. 1. What are the priorities for preservation of built works where degradation is accelerated by global environmental shifts? 2. What does one preserve of past cultures when the physical ground it once occupied is gone? 3. What are the methods for Historic Preservation when to preserve means much more than stabilizing a built project in time but also includes the preservation/sustenance of the land, the environment, and the cultural relevance? 4. If one cannot physically preserve does that mean its presence and cultural significance is nullified? To investigate these questions, the research team selected Fort Proctor, a NHRP site at extreme environmental risk. Fort Proctor is one of several forts built along Lake Borgne in Southeastern Louisiana following the War of 1812. Since then, Fort Proctor has remained in a fluctuating landscape as a static marker or datum, recording major ecological changes within the dynamic coastal environment. To understand the structure’s deconstruction and degradation as well as the changing Gulf of Mexico ecologies, a rich historical context was assembled from a complex array of disparate datasets (physical site and geographical condition surveys, material analyses, photogrammetric and photographic documentation, and GIS mapping.) From the data, the researchers developed time-based animations that explore the test site in four time-scales; one day, one year, 200 years, and geologic time. The animations present perspectival visualizations that illustrate the aesthetic and atmospheric qualities for each scale while overlaying analytical data and historical facts. -

The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 8-8-2007 The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands Lon Boudreaux Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Boudreaux, Lon Jr., "The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 564. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/564 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies By Lon J. Boudreaux Jr. B.S. Our Lady of Holy Cross College, 1992 M.S. University of New Orleans, 2007 August, 2007 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................. -

AERIAL LIDAR SURVEY Chef Menteur Project

AERIAL LIDAR SURVEY Chef Menteur Project February 17, 2017 Submitted to: Matt Conn Director of Operations SEG Environmental LLC 224 Rue De Jean Lafayette, LA 70508 Submitted by: Fugro, Inc. 200 Dulles Drive Lafayette, Louisiana 70506 Job No. 22.17800026 A member of the Fugro group of companies with offices throughout the world. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GPS NETWORK SUMMARY AND MAP 2.0 CONTROL DESCRIPTION SHEETS 3.0 FIELD NOTES 1.0 GPS NETWORK SUMMARY AND MAP SEG Chef Menteur Fugro Job # 22.17800026 February 2017 GPS PUB. PUB. NAVD 88 GEOID 09 NAVD 88 DELTA NAME POSITION ELLIP ELEV. HEIGHT ELEV. GPS NGS PID DESCRIPTION (NAD83) METERS METERS METERS METERS METERS BORG 30 04 15.16783 N -23.711 2.577 -26.288 2.589 -0.012 BH1134 Vertical Offset of "E 3146" 89 48 05.02694 W FTPK 30 09 56.40531 N -24.835 1.682 -26.517 1.723 -0.041 BH1164 Vertical Offset of "PIKE RESET" 89 44 20.88068 W MARY 30 01 22.70956 N -22.901 3.272 -26.173 DO8512 MARY_289 LSU C4G CORS ARP 89 54 46.80194 W MSIN 30 18 42.20573 N -17.309 9.739 -27.049 DN8737 INFINITY CENTER CORS ARP 89 36 15.50727 W SJHS 30 16 49.45698 N -12.897 13.849 -26.746 GulfNet SJHS 89 46 47.85767 W Note: The positions of the stations listed above are referenced to NAD83 (2011) (EPOCH 2010.0) horizontally & NAVD88 vertically. These coordinates were used as control for the FLI-MAP survey performed in February 2017. -

PORT DIRECTORY 2013 Portdirectory 2012 Portdirectory 12/3/12 1:41 PM Page 5

PortDirectory2012_COVERS_PortDir Cover 11/30/12 10:30 AM Page 991 PORT DIREC2013 TORY The official directory of the Port of New Orleans P.O. Box 60046, New Orleans, LA 70160 | 800.776.6652 | www.portno.com PortDirectory2012_COVERS_PortDir Cover 11/30/12 10:30 AM Page 992 PortDirectory_2012_PortDirectory 11/30/12 9:45 AM Page 1 FLEET STRENGTH After over 120 years of assisting vessels on the Mississippi River, we have more experience in more situations than anyone on the river. And we pass that experience on to our Captains every day - Captains who have been with Bisso for an average of over 24 years. Now, heading into our third century of operation, Bisso continues to invest in the best tugs for every possible job. Over the last 15 years, we’ve spent over $30 million on eight new tugs, including the first Z-drive tractor tug built on the lower Mississippi. And we will be adding our fourth Z-drive tractor tug in 2011. Today, we offer clients more security, maneuverability and horsepower with the largest fleet of twin screw, triple screw and tractor tugs on the Mississippi. This means we can send fewer tugs to do your jobs at a better overall price. So next time you’re looking for an assist on the Mississippi River, go with Bisso. AGENTS IN: BERGEN | LONDON | TOKYO | PUSAN Mailing address: P.O. Box 4250 • New Orleans LA 70178 Office: 13959 River Road • Luling LA 70070 504.861.1411 (24 hours) • fax: 504.861.3545 • www.bissotowing.com PortDirectory_2012_PortDirectory 11/30/12 9:45 AM Page 2 BEST EQUIPMENT, BEST CREWS, BEST SERVICE UNPARALLELED GUARANTEE LEADERS OF THE PACK E.N. -

Hurricane Irma Storm Review

Hurricane Irma Storm Review November 11, 2018 At Duke Energy Florida, we power more than 4 million lives Service territory includes: . Service to 1.8 million retail customers in 35 counties . 13,000 square miles . More than 5,100 miles of transmission lines and 32,000 miles of distribution lines . Owns and operates nearly 9,500 MWs of generating capacity . 76.2% gas, 21% coal, 3% renewable, 0.2%oil, 2,400 MWs Purchased Power. 2 Storm Preparedness Activities Operational preparation is a year-round activity Coordination with County EOC Officials . Transmission & Distribution Systems Inspected and . Structured Engagement and Information Maintained Sharing Before, During and After Hurricane . Storm Organizations Drilled & Prepared . Coordination with county EOC priorities . Internal and External Resource Needs Secured . Public Communications and Outreach . Response Plan Tested and Continuously Improved Storm Restoration Organization Transmission Hurricane Distribution System Preparedness System Local Governmental Coordination 3 Hurricane Irma – Resources & Logistics Resources . 12,528 Total Resources . 1,553 pre-staged in Perry, Georgia . 91 line and vegetation vendors from 25 states . Duke Energy Carolinas and Midwest crews as well as resources from Texas, New York, Louisiana, Colorado, Illinois, Oklahoma, Minnesota, Maine and Canada . 26 independent basecamps, parking/staging sites Mutual Assistance . Largest mobilization in DEF history . Mutual Assistance Agreements, executed between DEF and other utilities, ensure that resources can be timely dispatched and fairly apportioned. Southeastern Electric Exchange coordinates Mutual Assistance 4 5. Individual homes RESTORATION 3. Critical Infrastructure 2. Substations 1. Transmission Lines 4. High-density neighborhoods 5 Hurricane Irma- Restoration Irma’s track northward up the Florida peninsula Restoration Summary resulted in a broad swath of hurricane and tropical Customers Peak Customers Outage storm force winds. -

Background Hurricane Katrina

PARTPART 33 IMPACTIMPACT OFOF HURRICANESHURRICANES ONON NEWNEW ORLEANSORLEANS ANDAND THETHE GULFGULF COASTCOAST 19001900--19981998 HURRICANEHURRICANE--CAUSEDCAUSED FLOODINGFLOODING OFOF NEWNEW ORLEANSORLEANS •• SinceSince 1559,1559, 172172 hurricaneshurricanes havehave struckstruck southernsouthern LouisianaLouisiana ((ShallatShallat,, 2000).2000). •• OfOf these,these, 3838 havehave causedcaused floodingflooding inin NewNew thethe OrleansOrleans area,area, usuallyusually viavia LakeLake PonchartrainPonchartrain.. •• SomeSome ofof thethe moremore notablenotable eventsevents havehave included:included: SomeSome ofof thethe moremore notablenotable eventsevents havehave included:included: 1812,1812, 1831,1831, 1860,1860, 1915,1915, 1947,1947, 1965,1965, 1969,1969, andand 20052005.. IsaacIsaac MonroeMonroe ClineCline USWS meteorologist Isaac Monroe Cline pioneered the study of tropical cyclones and hurricanes in the early 20th Century, by recording barometric pressures, storm surges, and wind velocities. •• Cline charted barometric gradients (right) and tracked the eyes of hurricanes as they approached landfall. This shows the event of Sept 29, 1915 hitting the New Orleans area. • Storm or tidal surges are caused by lifting of the oceanic surface by abnormal low atmospheric pressure beneath the eye of a hurricane. The faster the winds, the lower the pressure; and the greater the storm surge. At its peak, Hurricane Katrina caused a surge 53 feet high under its eye as it approached the Louisiana coast, triggering a storm surge advisory of 18 to 28 feet in New Orleans (image from USA Today). StormStorm SurgeSurge •• The surge effect is minimal in the open ocean, because the water falls back on itself •• As the storm makes landfall, water is lifted onto the continent, locally elevating the sea level, much like a tsunami, but with much higher winds Images from USA Today •• Cline showed that it was then northeast quadrant of a cyclonic event that produced the greatest storm surge, in accordance with the drop in barometric pressure. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J.