Salary & Benefits Schedule and Teacher Tenure Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - ALASKA Allocations Under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - ALASKA Allocations under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Title I Allocations LEA ID District Under the Recovery Act* 200050 ALASKA GATEWAY SCHOOL DISTRICT 177,288 200010 ALEUTIAN REGION SCHOOL DISTRICT 0 200007 ALEUTIANS EAST BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 30,868 200180 ANCHORAGE SCHOOL DISTRICT 11,958,844 200525 ANNETTE ISLAND SCHOOL DISTRICT 42,947 200020 BERING STRAIT SCHOOL DISTRICT 1,243,321 200030 BRISTOL BAY BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 16,708 200730 CHATHAM REGION SCHOOL DISTRICT 77,515 200800 CHUGACH SCHOOL DISTRICT 67,956 200070 COPPER RIVER SCHOOL DISTRICT 102,745 200060 CORDOVA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 44,208 200090 CRAIG CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 63,749 200100 DELTA GREELY SCHOOL DISTRICT 179,840 200770 DENALI BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 20,131 200120 DILLINGHAM CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 113,507 200600 FAIRBANKS NORTH STAR BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRIC 2,862,001 200130 GALENA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 0 200270 HAINES BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 64,420 200300 HOONAH CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 29,732 200330 HYDABURG CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 51,500 200520 IDITAROD AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT 258,111 200210 JUNEAU BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 524,756 200360 KAKE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 42,516 200005 KASHUNAMIUT SCHOOL DISTRICT 178,840 200390 KENAI PENINSULA BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 1,756,792 200150 KETCHIKAN GATEWAY BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 328,811 200450 KLAWOCK CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 53,117 200480 KODIAK ISLAND BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 259,023 200760 KUSPUK SCHOOL DISTRICT 296,366 200485 LAKE AND PENINSULA SCHOOL DISTRICT 113,994 200001 LOWER -

Registered School Board Members & Superintendents for the Fly-In

Full Name Company Title Jackson, Tiffany Aleutians East Borough School District Board Member Smith, Hillary Aleutians East Borough School District School Board Member Marsett, Starr Anchorage School District School Board Vice President Bishop, Dr. Deena Anchorage School District Superintendent Atkinson, Tia Annette Island School District Board President Vlasoff, Roseline Chugach School District School Board Member Totemoff, David Chugach School District School Board Member Vlasoff, Gwen Chugach School District School Board Member Graham, Frankie Chugach School District School Board Vice President Arneson, Charlene Chugach School District School Board President Hanley, Michael Chugach School District Superintendent Hoepfner, Peter Cordova School District Board Member Hamm, Jenna Denali Borough School District Board Member Tench, James Denali Borough School District Board Member Ferguson, Sasha Denali Borough School District Executive Administrative Assistant Polta, Dan Denali Borough School District Superintendent Merriner, Jim Galena City School District Assistant Superintendent Huntington, Fred Galena City School District Board Vice President Sam, Susie Galena City School District Board President Villarreal, Grace Hoonah City Schools School Board Member Jewell, Heidi Hoonah City Schools Vice President Hutton, Robert Hoonah City Schools School Board President Morris, Bonnie Hydaburg City School Board President Story, Andi Juneau School District Board Clerk Johnson, Charley Kake City School District Board Member Bean Jr., William Kake City -

Title I District Improvement List Level 1 and Above Level 1 Districts Level 1 ‐ Alert: Consult with the Department Regarding Reasons for Not Meeting AYP

2012‐2013 Title I District Improvement List Level 1 and Above Level 1 Districts Level 1 ‐ Alert: Consult with the Department regarding reasons for not meeting AYP. Aleutians East Borough School District ** Chatham School District ** Chugach School District ** Copper River School District ** Hoonah City School District ** Hydaburg City School District ** Klawock City School District ** Nenana City School District ** Petersburg City School District ** Pribilof School District ** Southeast Island School District ** Tanana City School District ** Valdez Cityl Schoo District ** Wrangell Public School District Level 2 Districts Level 2 and 3 ‐ District Improvement: District shall develop, issue, and implement a district improvement plan, submit the plan to the Department, request technical assistance from the Department, and provide notice to parents. District must spend 10% of its Title I allocation on professional development. Denali Borough School District Craig City School District ** Kenai Peninsula Borough School District Sitka School District ** Saint Mary's School District Level 3 Districts Delta‐Greely School District ** Ketchikan Gateway Borough School District ** Level 4 Districts Level 4 ‐ Corrective Action: District shall continue to implement a district improvement plan, submit the plan to the Department, request technical assistance from the Department, provide notice to parents, and spend 10% of Title I allocation on professional development. The Department must take one or more corrective actions. Alaska Gateway School District -

Superintendents of Alaska 2013-2014 Alaska Gateway School District Aleutian Region Schools Aleutians East Bor

Superintendents of Alaska 2013-2014 Alaska Gateway School District Aleutian Region Schools Aleutians East Bor. School District Anchorage School District PO Box 226, Tok, Alaska 99780 PO Box 92230, Anchorage, AK 99509 PO Box 429, Sand Point, AK 99661 5530 E Northern Lights Blvd, Anc. AK 99504 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 883-5151 x102 Fax: 883-5154 Tel: 277-2648 Fax: 277-2649 Tel: 383-5222 Fax: 383-3496 Tel: 742-4312 Fax: 742-4318 Todd Poage, Superintendent Joseph Beckford, Superintendent Doug Conboy, Superintendent Ed Graff, Superintendent Annette Islands School District Bering Strait School District Bristol Bay Bor. School District Chatham School District PO Box 7, Metlakatla, AK 99926 PO Box 225, Unalakleet, AK 99684- PO Box 169, Naknek, AK 99633 PO Box 109, Angoon, AK 99820 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tel: 886-6332 Fax: 886-5130 Tel: 624-4275 Fax: 624-3078 Tel: 246-4225 Fax: 246-6857 Tel: 788-3302x 3103 Fax: 788-3252 Gene Avey, Superintendent Brett Agenbroad, Superintendent Bill Hill, Superintendent Scott Butterfield, Superintendent Chugach School District Copper River School District Cordova City School District Craig City School District 9312 Vanguard Dr., Anch, AK 99507 PO Box 108, Glennallen, AK 99588 PO Box 140, Cordova, AK 99574 PO Box 800, Craig, AK 99921 Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 522-7400 Fax: 522-3399 Tel: 822-3234 x223 Fax: 822-3949 Tel: 424-3265 Fax: 424-3271 Tel: 826-3274 Fax: 826-3322 Bob Crumley, Superintendent Michael Johnson, Ph.D., Superintendent Theresa Keel, Superintendent Jack Walsh, Superintendent Delta/Greely School District Denali Bor. -

Alaska Gateway School District Aleutian Region School District

2019-2020 Alaska Superintendents Association Contact Sheet Alaska Gateway School District Aleutian Region School District Aleutians East Borough School District PO Box 226, Tok, AK 99780-0226 PO Box 92230, Anchorage, AK 99509 PO Box 429, Sand Point, AK 99661-0429 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: https://www.agsd.us Web: http:// www.aleutregion.org/ Web: http://www.aebsd.org Tel: 883-5151 x101 Fax: 883-5154 Tel: 277-2648 Fax: 277-2649 Tel: 383-5222 x 7001 Fax: 383-3496 Scott MacManus, Superintendent Michael Hanley, Superintendent Patrick Mayer, Superintendent Anchorage School District Annette Island School District Bering Strait School District 5530 E Northern Lights Blvd, Anc. AK 99504 PO Box 7, Metlakatla, AK 99926-0007 PO Box 225, Unalakleet, AK 99684-0225 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.asdk12.org/ Web: http://aisd.k12.ak.us/ Web: http://www.bssd.org/ Tel: 742-4312 Fax: 742-4401 Tel: 886-6332 Fax: 886-5130 Tel: 624-4275 Fax: 624-3078 Dr. Deena Bishop, Superintendent Taw Lindsey, Superintendent Dr. Bobby Bolen, Superintendent Bristol Bay Borough School District Chatham School District Chugach School District PO Box 169, Naknek, AK 99633-0169 PO Box 109, Angoon, AK 99820-0109 9312 Vanguard Dr., Ste.100, Anch, AK 99507 E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.bbbsd.net Web: http://ak01001788.schoolwires.net Web: http://www.chugachschools.com/ Tel: 246-4225 Fax: -

Election District Report

Fiscal Year 1994 Election District Report Legislative Finance Division ~j P.O. Box WF Juneau, Alaska 99811 (907) 465-3795 ELECTION DISTRICT REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS ELECTION DISTRICT PAGE Summaries .............................................................................................................................................................. III - V 01 Ketchikan .......................................................................................................................................... ........................... I 02 SitkaIPetersburglWrangell ................................................. ................. .......................... ...... .... ................ .............. ...... 5 03 Juneat:t Downtown .......................................................................................................................................... ............. 9 04 MendenhalllLynn Canal ........................... '" ....................... .... .... ................ ...... .... ....... .... ........ ................... ...... ... ...... 13 05 Southeast Islands....................................................................................................................................... ................. 17 06 Kodiak ........................................................................................................................................................................ 23 07 HomerlKalifonsky .................................................................................................................................................... -

Fiscal Year 2018 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - ALASKA

Fiscal Year 2018 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - ALASKA FY 2018 Title I LEA ID District Allocation* 200050 Alaska Gateway School District 201,305 200010 Aleutian Region School District 42,622 200007 Aleutians East Borough School District 45,632 200180 Anchorage School District 14,156,959 200525 Annette Island School District 122,848 200020 Bering Strait School District 1,589,697 200030 Bristol Bay Borough School District 55,812 200730 Chatham School District 144,315 200800 Chugach School District 83,007 200070 Copper River School District 193,302 200060 Cordova City School District 15,408 200090 Craig City School District 200,125 200100 Delta/Greely School District 283,103 200770 Denali Borough School District 37,152 200120 Dillingham City School District 228,045 200600 Fairbanks North Star Borough School District 3,446,726 200130 Galena City School District 36,534 200270 Haines Borough School District 111,480 200300 Hoonah City School District 102,440 200330 Hydaburg City School District 75,583 200520 Iditarod Area School District 177,224 200210 Juneau Borough School District 830,500 200360 Kake City School District 69,808 200005 Kashunamiut School District 454,944 200390 Kenai Peninsula Borough School District 3,284,752 200150 Ketchikan Gateway Borough School District 557,863 200450 Klawock City School District 89,050 200480 Kodiak Island Borough School District 395,303 200760 Kuspuk School District 345,453 200485 Lake and Peninsula Borough School District 300,570 200001 Lower Kuskokwim School District 3,119,082 200003 -

BUD COMMITTEE -1- March 10, 2015 ALASKA STATE LEGISLATURE LEGISLATIVE BUDGET and AUDIT COMMITTEE March 10, 2015 7:33 A.M. MEMBER

ALASKA STATE LEGISLATURE LEGISLATIVE BUDGET AND AUDIT COMMITTEE March 10, 2015 7:33 a.m. MEMBERS PRESENT Representative Mike Hawker, Chair Representative Sam Kito Senator Lyman Hoffman Senator Cathy Giessel Senator Click Bishop MEMBERS ABSENT Senator Anna MacKinnon, Vice Chair Senator Bert Stedman Senator Pete Kelly (alternate) Representative Kurt Olson Representative Lance Pruitt Representative Steve Thompson Representative Mark Neuman (alternate) OTHER LEGISLATORS PRESENT Representative Paul Seaton Representative Lora Reinbold COMMITTEE CALENDAR AGENDA: PUBLIC INPUT ON SCHOOL FUNDING STUDY PREVIOUS COMMITTEE ACTION No previous action to record WITNESS REGISTER JUSTIN SILVERSTEIN Augenblick, Palaich and Associates (APA) Consulting Denver, Colorado POSITION STATEMENT: Testified as a member of the consulting team reviewing the Alaska educational funding formula mechanism. JOSEPH REEVES, Executive Director BUD COMMITTEE -1- March 10, 2015 Association of Alaska School Boards (AASB) Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. DAVID MEANS, Director of Administrative Services Juneau School District Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. MARK MILLER, Superintendent Juneau School District Juneau, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. LINCOLN SAITO, Chief Operating Officer North Slope Borough School District Barrow, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. DAVE JONES, Assistant Superintendent Instructional Support Kenai Peninsula Borough School District Soldotna, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. DAVID PIAZZA, Superintendent Southwest Region School District Dillingham, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. P. J. Ford Slack, Interim Superintendent Hoonah City School District Hoonah, Alaska POSITION STATEMENT: Testified during discussion of the school funding formula. -

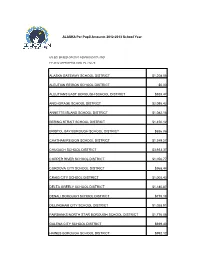

Alaska Gateway School District $1,208.06 Aleutian

ALASKA Per Pupil Amounts 2012-2013 School Year US ED: BASED ON 2010 CENSUS DATA AND FY 2012 APPROPRIATION, PL 112-74 ALASKA GATEWAY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,208.06 ALEUTIAN REGION SCHOOL DISTRICT $0.00 ALEUTIANS EAST BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $935.47 ANCHORAGE SCHOOL DISTRICT $2,095.42 ANNETTE ISLAND SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,082.18 BERING STRAIT SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,450.12 BRISTOL BAY BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $856.06 CHATHAM REGION SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,349.27 CHUGACH SCHOOL DISTRICT $3,933.37 COPPER RIVER SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,056.77 CORDOVA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $968.44 CRAIG CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,005.43 DELTA GREELY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,180.87 DENALI BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $715.18 DILLINGHAM CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,028.91 FAIRBANKS NORTH STAR BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,776.06 GALENA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $939.40 HAINES BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $992.12 HOONAH CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,181.58 HYDABURG CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $2,520.88 IDITAROD AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,645.38 JUNEAU BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,556.96 KAKE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,675.79 KASHUNAMIUT SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,554.43 KENAI PENINSULA BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,692.27 KETCHIKAN GATEWAY BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $978.87 KLAWOCK CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,280.64 KODIAK ISLAND BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $919.41 KUSPUK SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,650.53 LAKE AND PENINSULA SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,292.44 LOWER KUSKOKWIM SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,268.35 LOWER YUKON SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,486.26 MATANUSKA-SUSITNA BOROUGH SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,789.15 NENANA CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $1,266.52 NOME CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT $915.79 NORTH SLOPE BOROUGH -

Association of Alaska School Boards

2018-19 Membership Directory (Updated January 21, 2019) Alaska Gateway School District Aleutians East Borough School District PO Box 226, Tok, Alaska 99780-0226 PO Box 429, Sand Point, AK 99661-0429 E-mail: [email protected] Association of E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.agsd.us Web: http://www.aebsd.org Tel: 883-5151 x102 Fax: 883-5154 Alaska School Tel: 383-5222 Fax: 383-3496 Scott MacManus, Superintendent Michael Seifert, Superintendent Deb Sparks, Executive Admin. Asst. Boards Jade Gundersen, Executive Admin. Asst. Advocates for Alaska's Youth School Board School Board Peter Talus, President 1111 W. 9th St Tiffany Jackson, President Jeff Deeter Lorraine Titus Juneau, AK 99801 Brenda Wilson Hillary Smith Frank Cook Steve Robbins Jacki Brandell Susan Osterback Daisy Northway Mike Cronk 907-463-1660 Rayette McGlashan Arlene Wilson fax 907-586-2995 [email protected] www.aasb.org Anchorage School District Annette Islands School District Bering Strait School District 5530 E Northern Lights Blvd, Anchorage AK 99504 PO Box 7, Metlakatla, AK 99926-0007 PO Box 225, Unalakleet, AK 99684-0225 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.asdk12.org Web: http://aisd.k12.ak.us Web: http://www.bssd.org Tel: 742-4312 Fax: 742-4318 Tel: 886-6332 Fax: 886-5130 Tel: 624-4266 Fax: 624-3078 Dr. Deena Bishop, Superintendent Tim Bauer, Superintendent Robert Bolen, Superintendent Janet Hayes, Exec. Asst. (Superintendent) Brittany Leask, Executive Admin. Asst. Marty Towarak, Executive Admin. Asst. Katy Grant, Exec. Asst. (School Board) School Board School Board School Board Starr Marsett, President Tia Atkinson, President Annabelle Cunningham, President Deena Mitchell Andy Holleman Darcy Booth Deanna Nelson Annie Weyiouanna Robert Tokeinna, Jr Mark Foster Alisha Hilde Bruce Janes Lucione Leisholmn Jane Kava Robert Dickens Elisa Snelling Dave Donley Aaron Iworrigan Irene Navarro Jeanette Iya Winfred Olanna Jr. -

Correspondence List

Program Name Statewide or District District Name Address POCName City POCTitle Zip POCEmail PrgmWebsite Phone AKTEACH District Program Kodiak Island Borough School District 722 Mill Bay Road Lisa Cavan Kodiak K‐12 Homeschool Cordinator 99615 [email protected] http://www.akteach.com (907) 486‐7545 Alaska REACH Academy Statewide Program Alaska Gateway School District Box 454 LeAnn Young Tok Program Director 99780 [email protected] http://www.reachacademy.us/ (907) 883‐2591 Bristol Bay Correspondence District Program Bristol Bay Borough School District P.O. Box 169 Nick Popp Naknek Coordinator 99633 [email protected] http://www.bbbsd.net/ (907) 246‐4225 Cordova Innovative Learning Program District Program Cordova School District P.O. Box 1330 Kate Williams Cordova Principal 99574 [email protected] https://www.cordovasd.org/District/Department/13‐Innovative‐Learning‐Program (907) 425‐3265 CyberLynx Statewide Program Nenana City Schools District P.O. Box 599 Brian Rozell Nenana Principal 99760 [email protected] https://cyberlynx.org/ (907) 832‐5423 Delta‐Greely Homeschool District Program Delta‐Greely School District P.O. Box 396 Holly Stewart Delta Junction Contact Teacher 99737 [email protected] http://www.dgsd.us/District/Department/11‐Delta‐Greely‐Homeschool (907) 895‐1043 Denali PEAK Statewide Program Denali Borough School District 4240 Old Seward Hwy Suite #4 Dan Polta Anchorage Superintendent 99503 [email protected] https://www.dbsd.org/Peak (907) 563‐0990 Dillingham Correspondence District Program Dillingham School District P.O. -

Chugach School District I • B

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 • APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE Indian Demonstration Grants for Indian Children CFDA # 84.299A PR/Award # S299Al60008 Gramts.gov T racking#: GRANT121711 73 OMB No. 1810-0722, Expiration Date: 06/30n018 Closing Date: MaUJ., 2016 PR/Award# S299Al60008 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 Attachment- 1 (1236-CSD_VTE_G/_424-14) e6 2. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 4248) e7 3. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e9 4. ED GEPA427 Form e10 Attachment- 1 {1235-CSD_ VTE_Gl_GEPA) e11 5. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e12 6. ED Abstract Narrative Form e13 Attachment- 1 (1234-CSD_ VTE_ Gl_Abstract) e14 7. Project Narrative Form e16 Attachment- 1 (1240-CSD_ VTE_ Gl_Project_Narrative) e17 8. Other Narrative Form e53 Attachment 1 (1238-CSD_ VTE_ Gl_Attachments) e54 Attachment-2 (1239-CSD_ VTE_Gl_Attachment_Optional) e1 06 9. Budget Narrative Form e117 Attachment - 1 (1237-CSD_ VTE_Gl_Budget_Narrative) e118 10. Form ED_SF424_ Supplement_1_3-V1.3.pdf e121 11 . Form ED_524_Budget_ 1_3-Vt.3.pdf e122 This application was generated using the PDF functionality. The PDF functionality automatically numbers the pages in this application. Some pages/sections of this application may contain 2 sets of page numbers. one set created by the applicant and the other set created by e·Application's PDF functionality. Page numbers created by the e·Application PDF functionality will be preceded by the letter e (for example, e t , e2, e3, etc.). Page e2 OMB Number: 4040-0004 Expiration Date: 8/31/2016 Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 • 1.