Purple Loosestrife Best Management Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filipendula Ulmaria (L.) Maxim

6 May 2020 EMA/HMPC/595722/2019 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) Addendum to Assessment report on Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. (= Spiraea ulmaria L.), herba Rapporteur(s) B Kroes Assessor(s) Jan van der Nat Peer-reviewer J Wiesner HMPC decision on review of monograph Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. (= Spiraea 30 January 2018 ulmaria L.), herba adopted on July 2011 Call for scientific data (start and end date) From 30 April 2018 to 31 July 2018 Adoption by Committee on Herbal Medicinal 6 May 2020 Products (HMPC) Review of new data on Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim., herba Periodic review (from 2011 to 2018) Scientific data (e.g. non-clinical and clinical safety data, clinical efficacy data) Pharmacovigilance data (e.g. data from EudraVigilance, VigiBase, national databases) Scientific/Medical/Toxicological databases: Scopus, PubMed, Embase, ToxNet Other Regulatory practice Old market overview in AR (i.e. products fulfilling 30/15 years on the market) New market overview (including pharmacovigilance actions taken in member states) – information from Member States (reporting between November 2018 and January 2019): Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Referral Ph.Eur. monograph: Filipendulae ulmariae herba 04/2013:1868 Currently: request for revision: replacement of hexane in TLC identification. Other Consistency (e.g. scientific decisions taken by HMPC) Public statements or other decisions taken by HMPC Consistency with other monographs within the therapeutic area Other Availability of new information (i.e. -

RHS the Garden Magazine Index 2020

GardenThe INDEX 2020 Volume 145, Parts 1–12 Index 2020 January 2020 February 2020 March 2020 April 2020 May 2020 June 2020 1 2 3 4 5 6 Coloured numbers campestre ‘William ‘Voodoo’ 9: 78 ‘Kaleidoscope’ lauterbachiana Plas Brondanw, North in bold before the page Caldwell’ 3: 32, 32 ‘Zwartkop’ 7: 22, 22; 11: 46, 46 1: 56, 57 Wales 12: 38–42, 38–42 number(s) denote the x freemanii Autumn 8: 54, 54 ‘Lavender Lady’ 6: 12, macrorrhizos 11: 33, 33 Andrews, Susyn, on: part number (month). Blaze (‘Jeffersred’) Aeschynanthus 3: 138 12; 11: 46–47, 47 micholitziana 2: 78 hollies, AGM cultivars Each part is paginated 10: 14, 14–15 Aesculus ‘Macho Mocha’ Aloe Safari Sunrise (‘X5’) 12: 31, 31 separately. griseum 1: 49; 2: 14, 14– hippocastanum 11: 46, 47 6: 12, 12 Anemone: 15; 11: 34, 35; 12: 10, 10; ‘Hampton Court ‘Mayan Queen’ 11: 46 Aloysia: ‘Frilly Knickers’ 9: 7, 7 Numbers in italics 12: 83 Gold’ 3: 89, 89 ‘Pineapple Express’ citrodora (lemon Wild Swan denote an image. micrantham 10: 80 ‘Wisselink’ 3: 89, 89 11: 47 verbena) 6: 87, 87, 88; (‘Macane001’) 5: 74, palmatum 4: 74–75; x neglecta ‘Silver Fox’ 11: 47 to infuse gin 4: 82, 83 74, 76 Where a plant has a 12: 65, 65 ‘Erythroblastos’ Aglaonema (Chinese gratissima angelica root to infuse Trade Designation ‘Garnet’ 10: 27, 27 3: 88, 88 evergreen): 1: 57; 7: 34, (whitebrush or gin 4: 82, 82 (also known as a selling platanoides Agapanthus: 5: 82, 83 34; 12: 32, 32 spearmint verbena) Angelonia Serena Series name) it is typeset in ‘Walderseei’ 3: 87, 87 ‘Blue Dot 9: 109 ‘King of Siam’ 1: 56, 57 6: 86, 88 8: 16, 17 a different font to pseudoplatanus ‘Bressingham Blue’ pictum ‘Tricolor’ Alstroemeria: angel’s trumpet (see distinguish it from the ‘Brilliantissimum’ 9: 109 1: 44, 45 Indian Summer Brugmansia) cultivar name (shown 3: 86, 86–87 ‘Cally Blue 9: 109 Agrostis nebulosa (‘Tesronto’) 8: 16, 16 Angwin, Kirsty, on: in ‘Single Quotes’). -

OSU Gardening with Oregon Native Plants

GARDENING WITH OREGON NATIVE PLANTS WEST OF THE CASCADES EC 1577 • Reprinted March 2008 CONTENTS Benefi ts of growing native plants .......................................................................................................................1 Plant selection ....................................................................................................................................................2 Establishment and care ......................................................................................................................................3 Plant combinations ............................................................................................................................................5 Resources ............................................................................................................................................................5 Recommended native plants for home gardens in western Oregon .................................................................8 Trees ...........................................................................................................................................................9 Shrubs ......................................................................................................................................................12 Groundcovers ...........................................................................................................................................19 Herbaceous perennials and ferns ............................................................................................................21 -

Meadowsweet 2015

ONLINE SERIES MONOGRAPHS The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products Filipendulae ulmariae herba Meadowsweet 2015 www.escop.com The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products FILIPENDULAE ULMARIAE HERBA Black Cohosh 2015 ESCOP Monographs were first published in loose-leaf form progressively from 1996 to 1999 as Fascicules 1-6, each of 10 monographs © ESCOP 1996, 1997, 1999 Second Edition, completely revised and expanded © ESCOP 2003 Second Edition, Supplement 2009 © ESCOP 2009 ONLINE SERIES ISBN 978-1-901964-37-0 Filipendulae ulmariae herba - Meadowsweet © ESCOP 2015 Published by the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP) Notaries House, Chapel Street, Exeter EX1 1EZ, United Kingdom www.escop.com All rights reserved Except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review no part of this text may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Important Note: Medical knowledge is ever-changing. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment may be required. In their efforts to provide information on the efficacy and safety of herbal drugs and herbal preparations, presented as a substantial overview together with summaries of relevant data, the authors of the material herein have consulted comprehensive sources believed to be reliable. However, in view of the possibility of human error by the authors or publisher of the work herein, or changes in medical knowledge, neither the authors nor the publisher, nor any other party involved in the preparation of this work, warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for results obtained by the use of such information. -

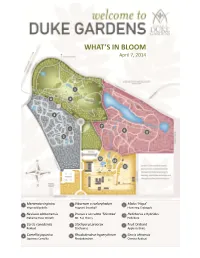

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

Purple Loosestrife Lythrum Salicaria L

Weed of the Week Purple Loosestrife Lythrum salicaria L. Native Origin: Eurasia- Great Britain, central and southern Europe, central Russia, Japan, Manchuria China, Southeast Asia, and northern India Description: Purple loosestrife is an erect perennial herb in the loosestrife family (Lythraceae), growing to a height of 3-10 feet. Mature plants can have 1 to 50 4-sided stems that are green to purple and often branching making the plant bushy and woody in appearance. Opposite or whorled leaves are lance-shaped, stalk-less, and heart-shaped or rounded at the base. Plants are usually covered by a downy pubescence. Flowers are magenta-colored with five to seven petals and bloom from June to September. Seeds are borne in capsules that burst at maturity in late July or August. Single stems can produce an estimated two to three million seeds per year from a single rootstock. The root system consists of a large, woody taproot with fibrous rhizomes. Rhizomes spread rapidly to form dense mats that aid in plant production. Habitat: Purple loosestrife is capable of invading wetlands such as freshwater wet meadows, tidal and non-tidal marshes, river and stream banks, pond edges, reservoirs, and ditches. Distribution: This species is reported from states shaded on Plants Database map. It is reported invasive in CT, DC, DE, ID, IN, KY, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, MO, NC, NE, NH, NJ, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, TN, UT, VA, VT, WA, and WI. Ecological Impacts: It spreads through the vast number of seeds dispersed by wind and water, and vegetatively through underground stems at a rate of about one foot per year. -

F a C T S H E E T Purple Loosestrife

JEFFERSON COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD F A C T S H E E T PURPLE LOOSESTRIFE (Lythrum salicaria) Purple loosestrife can be ten feet tall at maturity. The multiple stems are squarish with four to six sides. The leaves are up to four inches long, usually lance- shaped, with smooth edges. The magenta-colored flowers, which bloom from July to October, appear tightly clustered on tall spikes. Loosestrife family. LOOK ALIKES: Fireweed, (Epilobium angustifolium— native), commonly grows in drier ground than purple loosestrife, and does not have a square stem. Cooley’s hedgenettle, (Stachys cooleyae—native) seldom grows taller than four feet, and the plants are not branched or bushy. The leaves are nettle-like, with toothed edges. Butterfly bush, (Buddleja spp.), is a WHY BE CONCERNED? garden ornamental which invades riparian areas. It has a round stem, and Purple loosestrife invades wetlands and the bright purple flowers grow in a tightly displaces native vegetation. packed flower head. It supplies little food or habitat to wildlife. Purple loosestrife is a Class B Noxious Weed. Control is required in Jefferson County. Hardhack, (Spiraea douglasii— native), has a round stem and fluffy, pinkish flowers arranged in tight clusters. 380 Jefferson Street, Port Townsend WA 98368 360 379-5610 Ext. 205 [email protected] http://www.co.jefferson.wa.us/WeedBoard DISTRIBUTION: Purple loosestrife has been found in at least 8 locations in Jefferson County. Most are small, have been hand-pulled and will be monitored closely. One large infestation responded very well to bio-control. ECOLOGY: Purple loosestrife grows in wet sites, especially ones that have been disturbed by human activity. -

Purple Loosestrife May Impede Boat Travel

Pickeral Weed: Fireweed: Why Should Purple Pontederia cordata Epilobium angustifolium Loosestrife Concern Flowers 2-lipped, spikes Fatter spikes of 4-petaled, 3”-4”; leaves heart shaped, stalked flowers; alternate, You? single; water, 1’ to 3’ toothed leaves; northern plant of drier areas; 2’ to 6’ False Dragonhead: Plant diversity in wetlands Physostegia virginiana ✤ Tubular flowers, dissimilar petals; declines dramatically and toothed leaves; 1’ to 5’ (Other large mint many rare and endangered family plants: Hedge Nettle, Giant Hyssop) plants found in our remaining Swamp Loosestrife: Smartweed: wetlands are threatened. Decodon verticillatus Polygonum sp. Flowers bunched at (many native well-separated leaf species) - Tiny Most wetland animals that Look-a-likes ✤ bases; leaves whorled flowers, skinny depend on native plants for in 3s or 4s; stems spikes 1” to 4”; food and shelter decline usually arching, 1’ to 8’ alternate leaves clasp stem at base; significantly. Some species, stems jointed, 1’ to 6’ such as Baltimore butterflies, marsh wrens, and least bitterns may disappear entirely. Lupine: Blue Vervain: Lupinus perennis Verbena hastata Pea-like flowers; alternate, PURPLE (+ other Verbena sp.) ✤ Recreational uses of wetlands palm-like leaves; dry, LOOSESTRIFE Flowers tiny, pencil thin for hunting, trapping, fishing, sandy places; 2’ to 4’ spikes; toothed, oval, stalked leaves; moist bird watching and nature study to dry places; 2’ to 6’ decrease. Thick growth of purple loosestrife may impede boat travel. Winged Loosestrife: Steeplebush: ✤ Wetlands may store and filter Lythrum alatum Spiraea tomentosa less water. Smaller, single flowers DO NOT CONFUSE THESE Tiny flowers, conical at well-separated leaf set of flower spikes; bases; upper leaves NATIVE SPECIES WITH alternate, oval ✤ Millions of dollars spent to single; southern PURPLE LOOSESTRIFE! leaves; woody stem preserve wetlands would be prairies, 2’ to 3’ 1’ to 4’ wasted. -

(Lythrum Salicaria) an Invasive Threat to Freshwater Wetlands? Conflicting Evidence from Several Ecological Metrics

WETLANDS, Vol. 21, No. 2, June 2001, pp. 199±209 q 2001, The Society of Wetland Scientists IS PURPLE LOOSESTRIFE (LYTHRUM SALICARIA) AN INVASIVE THREAT TO FRESHWATER WETLANDS? CONFLICTING EVIDENCE FROM SEVERAL ECOLOGICAL METRICS Elizabeth J. Farnsworth New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, Massachusetts, USA 01701 E-mail: [email protected] Donna R. Ellis Department of Plant Science, Unit 4163 University of Connecticut Storrs, Connecticut, USA 06269 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Con¯icting interpretations of the negative impacts of invasive species can result if inconsistent measures are used among studies or sites in de®ning the dominance of these species relative to the com- munities they invade. Such con¯icts surround the case of Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), a widespread exotic wetland perennial. We describe here a 1999 study in which we quanti®ed stand characteristics of L. salicaria and associated vegetation in arrays of 30 1-m2 plots in each of ®ve wet meadows in Connecticut, USA. We explored linear and non-linear relationships of above-ground plant biomass, stem density, and indices of species richness, diversity, and composition to gradients of L. salicaria dominance, including stem density, percent cover, and biomass. Species richness, other diversity metrics, and stem density of other species were not signi®cantly correlated with the density or percent cover of L. salicaria stems. The relative importance values (number of quadrats in which they were found) of co-occurring species in low-density L. salicaria quadrats were signi®cantly correlated with their relative importance in high-density L. salicaria quadrats, indicating that only modest shifts in abundance occurred as L. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

Indiana Medical History Museum Guide to the Medicinal Plant Garden

Indiana Medical History Museum Guide to the Medicinal Plant Garden Garden created and maintained by Purdue Master Gardeners of Marion County IMHM Medicinal Plant Garden Plant List – Common Names Trees and Shrubs: Arborvitae, Thuja occidentalis Culver’s root, Veronicastrum virginicum Black haw, Viburnum prunifolium Day lily, Hemerocallis species Catalpa, Catalpa bignonioides Dill, Anethum graveolens Chaste tree, Vitex agnus-castus Elderberry, Sambucus nigra Dogwood, Cornus florida Elecampane, Inula helenium Elderberry, Sambucus nigra European meadowsweet, Queen of the meadow, Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba Filipendula ulmaria Hawthorn, Crateagus oxycantha Evening primrose, Oenothera biennis Juniper, Juniperus communis False Solomon’s seal, Smilacina racemosa Redbud, Cercis canadensis Fennel, Foeniculum vulgare Sassafras, Sassafras albidum Feverfew, Tanacetum parthenium Spicebush, Lindera benzoin Flax, Linum usitatissimum Witch hazel, Hamamelis virginiana Foxglove, Digitalis species Garlic, Allium sativum Climbing Vines: Golden ragwort, Senecio aureus Grape, Vitis vinifera Goldenrod, Solidago species Hops, Humulus lupulus Horehound, Marrubium vulgare Passion flower, Maypop, Passiflora incarnata Hyssop, Hyssopus officinalis Wild yam, Dioscorea villosa Joe Pye weed, Eupatorium purpureum Ladybells, Adenophora species Herbaceous Plants: Lady’s mantle, Alchemilla vulgaris Alfalfa, Medicago sativa Lavender, Lavendula angustifolia Aloe vera, Aloe barbadensis Lemon balm, Melissa officinalis American skullcap, Scutellaria laterifolia Licorice, Glycyrrhiza -

Common Name Scientific Name Type Plant Family Native

Common name Scientific name Type Plant family Native region Location: Africa Rainforest Dragon Root Smilacina racemosa Herbaceous Liliaceae Oregon Native Fairy Wings Epimedium sp. Herbaceous Berberidaceae Garden Origin Golden Hakone Grass Hakonechloa macra 'Aureola' Herbaceous Poaceae Japan Heartleaf Bergenia Bergenia cordifolia Herbaceous Saxifragaceae N. Central Asia Inside Out Flower Vancouveria hexandra Herbaceous Berberidaceae Oregon Native Japanese Butterbur Petasites japonicus Herbaceous Asteraceae Japan Japanese Pachysandra Pachysandra terminalis Herbaceous Buxaceae Japan Lenten Rose Helleborus orientalis Herbaceous Ranunculaceae Greece, Asia Minor Sweet Woodruff Galium odoratum Herbaceous Rubiaceae Europe, N. Africa, W. Asia Sword Fern Polystichum munitum Herbaceous Dryopteridaceae Oregon Native David's Viburnum Viburnum davidii Shrub Caprifoliaceae Western China Evergreen Huckleberry Vaccinium ovatum Shrub Ericaceae Oregon Native Fragrant Honeysuckle Lonicera fragrantissima Shrub Caprifoliaceae Eastern China Glossy Abelia Abelia x grandiflora Shrub Caprifoliaceae Garden Origin Heavenly Bamboo Nandina domestica Shrub Berberidaceae Eastern Asia Himalayan Honeysuckle Leycesteria formosa Shrub Caprifoliaceae Himalaya, S.W. China Japanese Aralia Fatsia japonica Shrub Araliaceae Japan, Taiwan Japanese Aucuba Aucuba japonica Shrub Cornaceae Japan Kiwi Vine Actinidia chinensis Shrub Actinidiaceae China Laurustinus Viburnum tinus Shrub Caprifoliaceae Mediterranean Mexican Orange Choisya ternata Shrub Rutaceae Mexico Palmate Bamboo Sasa