A Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Guitar Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

“Love God with the Guitar”

“Love God With the Guitar” Renato Bellucci Classical Guitarist & Author “To My Divine Wife Belén and our 7 children” The life of classical guitarist Renato Bellucci, his teaching, life experience, Catholic faith, and an introduction to the classical guitar technique. www.mangore.com This work is published for the greater Glory of God. The book is the intellectual property of Renato Bellucci and may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without written permission by the Publisher. Contact Renato Bellucci for permission: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. VOCATION ..................................................................................... 4 2. AN ENCOUNTER WITH GOD ........................................................... 7 3. S.D.G. Soli Deo Gloria ............................................................... 11 4. MY GUITAR HISTORY ................................................................... 14 5. ANDRES SEGOVIA ........................................................................ 16 6. NARCISO YEPES ........................................................................... 26 7. BACH ............................................................................................ 39 8. THE CHACONNE ........................................................................... 44 9. ABEL CARLEVARO ...................................................................... 48 10. GIVING CONCERTS .................................................................... 61 11. ANXIETY ................................................................................... -

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Nafme Council for Guitar

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Many schools today offer guitar classes and guitar ensembles as a form of music instruction. While guitar is a popular music choice for students to take, there are many teachers offering instruction where guitar is their secondary instrument. The NAfME Guitar Council collaborated and compiled lists of Guitar Best Practices for each year of study. They comprise a set of technical skills, music experiences, and music theory knowledge that guitar students should know through their scholastic career. As a Guitar Council, we have taken careful consideration to ensure that the lists are applicable to middle school and high school guitar class instruction, and may be covered through a wide variety of method books and music styles (classical, country, folk, jazz, pop). All items on the list can be performed on acoustic, classical, and/or electric guitars. NAfME Council for Guitar Education Best Practices Outline for a Year One Guitar Class YEAR ONE - At the completion of year one, students will be able to: 1. Perform using correct sitting posture and appropriate hand positions 2. Play a sixteen measure melody composed with eighth notes at a moderate tempo using alternate picking 3. Read standard music notation and play on all six strings in first position up to the fourth fret 4. Play melodies in the keys C major, a minor, G major, e minor, D major, b minor, F major and d minor 5. Play one octave scales including C major, G major, A major, D major and E major in first position 6. -

Cgsunynewsletter Volume 17 # 1 the Classical Guitar Society of Upstate New York

! CGSUNYNewsletter Volume 17 # 1 The Classical Guitar Society of Upstate New York www.cgsuny.org Phone: 607-865-8775 Address: P.O. Box 151 Unadilla, NY 13849 President’s Message Greetings one and all, I am very pleased to announce that it is now official that our featured soloist at this year’s (our 17th!) Fall Festival will be Gohar Vardanyan. Anyone interested in her, her playing, or her teaching can see several helpful lessonettes at the Strings By Mail website. I am very excited. I recently recalled a silly but actually helpful scene in a Hollywood movie. In Runaway Bride there is a scene where one of the Julia Roberts character’s jilted fiancés, a major Grateful Dead fan, upon finding out that her devotion to him (and to the Dead) was not what he thought, asked: “What would Jerry (Garcia) do?” The answer came back: “Play”. As we watch trouble of all kinds all around the world we should play- for ourselves and for others- and we should listen. Sharing music truly helps dispel the darkness. Paul Sweeny, CGSUNY President 2016 Headline Concert and Masterclass Review 2016 CGSUNY Fall Festival Concert and Masterclass with Celil Refik Kaya by Giancarlo Sidoli This year’s featured performer, Celil Refik Kaya presented a phenomenal concert. Beginning with brilliant performances of Mauro Giuliani’s Sonata Eroica op. 150, two well-arranged sets of keyboard transcriptions of J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Enrique Granados’ Valses Poeticos. The second half consisted of Celil’s own Sonatina, Rodrigo’s Toccata, the Eighteenth Caprichoso de Goya by Castelnuovo-Tedesco and ending with an amazing encore-a Turkish piece in which one could almost hear the oud and rebab’s instrumental influence! Celil, a student of 2014 featured performer Adam Holzman, is currently pursuing his DMA at the Butler School of Music at the University of Texas at Austin. -

MUSIC 158 Proceeds with Techniques and Compositions of Intermediate Level for Classical Guitar

COURSE OUTLINE : MUSIC 158 D Credit – Degree Applicable COURSE ID 001203 AUGUST 2020 COURSE DISCIPLINE : MUSIC COURSE NUMBER : 158 COURSE TITLE (FULL) : Classical Guitar III COURSE TITLE (SHORT) : Classical Guitar III CATALOG DESCRIPTION MUSIC 158 proceeds with techniques and compositions of intermediate level for classical guitar. Included for study are selected pieces from the Renaissance, Baroque, Classic and Romantic eras, as well as solo arrangements of familiar tunes. Knowledge of the entire fingerboard is further enhanced by the practice of two and three octave scales. Basic skills for transcribing music written for keyboard are introduced. CATALOG NOTES Note: This class requires the student to have a full-size guitar in playable condition. Total Lecture Units: 0.00 Total Laboratory Units: 1.00 Total Course Units: 1.00 Total Lecture Hours: 0.00 Total Laboratory Hours: 54.00 Total Laboratory Hours To Be Arranged: 0.00 Total Contact Hours: 54.00 Total Out-of-Class Hours: 0.00 Prerequisite: MUSIC 157 or equivalent. GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLLEGE --FOR COMPLETE OUTLINE OF RECORD SEE GCC WEBCMS DATABASE-- Page 1 of 4 COURSE OUTLINE : MUSIC 158 D Credit – Degree Applicable COURSE ID 001203 AUGUST 2020 ENTRY STANDARDS Subject Number Title Description Include 1 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II Analyze and perform music of greater Yes contrapuntal and rhythmic complexity; 2 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II observe and demonstrate variations in Yes volume; 3 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II incorporate proper techniques for slurs and Yes grace notes into music as required; 4 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II develop the ability to produce natural and Yes artificial harmonics; 5 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II extend familiarity with the fret board by Yes practicing scales in several positions; 6 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II construct basic triads in major and minor Yes keys and apply them to the comprehension of fretboard harmony. -

“Apoyando” and “Tirando” Related to Its Harmonic Components and Autocorrelation Function

Buenos Aires – 5 to 9 September, 2016 Acoustics for the 21st Century… PROCEEDINGS of the 22nd International Congress on Acoustics Music Perception: Paper ICA2016-227 Subjective preference of classical guitar strokes “apoyando” and “tirando” related to its harmonic components and autocorrelation function Joaquin Garcia(a), Shin-ichi Sato(b), Florent Masson(c) (a)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] (b)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] (c)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] Abstract Tone production of classical guitar performance is an essential part for musicians to transmit their sentimental and interpretative intentions. This work investigates subjective preferences of two common plucking techniques used by guitar players, apoyando (rest) and tirando (free) strokes. Six excerpts of classical guitar music with different tempos and range of frequency were performed using the two techniques and were recorded for the subjective tests. Two groups of subjects, guitar players and people who do not play guitar, were investigated to see if both groups evaluate the guitar timbre in different way or not. AB test was conducted with 50 persons for each group asking which technique is preferred and have more sound quality. Then the harmonic components and autocorrelation function (ACF) of each stroke were analysed to relate with the characteristics of the music program (tempo and frequency range) and subjective preferences. The effective duration of ACF is defined with the taue (τe) parameter. Results of the subjective test showed that harmonic content did not define preferences, but higher taue values of the ACF were correlated with a higher sound guitar quality. -

Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 7 Number 1 Spring Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Sparks, Paul (1997) "Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks By 1800 guitars with six single strings (tuned EAdgbe') had become the norm. The rosette gave way to an open sound hole, while the neck was lengthened and fitted with a raised fingerboard extending to the sound hole. Nineteen fixed metal frets eventually became standard, the top note sounding b". The bridge was raised, the body enlarged, and fan-strutting introduced beneath the table to support higher tension strings. Treble strings were made of gut (superseded by more durable nylon after World War 11), bass strings from metal wound on silk (or, more recently, nylon floss). Tablature became obsolete, guitar music being universally written in the treble clef, sounding an octave lower than written. By the 1820s makers such as Louis Panormo of London were replacing wooden tuning pegs with machine heads for more precise tuning, and creating the prototype of the modem classical guitar (a design perfected in mid-century by Antonio Torres). -

Toccata Classics TOCC0168 Notes

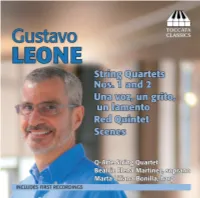

P GUSTAVO LEONE ON HIMSELF AND HIS MUSIC I am a porteño, a native of Buenos Aires, but since 1987 I have lived in Chicago, where I am a professor in the Department of Fine and Performing Arts of Loyola University Chicago. Before that, from 1994 to 2007, I was on the faculty at Columbia College, also in Chicago. I began my musical career as a classical guitarist in Argentina, studying with Luis Ainsestad, Adriana Ardizzone and Miguel Ángel Girollet. I attended the Guitar International Seminars at the University of Palestrina in Porto Alegre, Brazil, from 1976 to 1978, where I enjoyed Abel Carlevaro’s guitar-technique seminars as well as master-classes by eminent guitarists such as Sérgio Abreu and Eduardo Fernandez. In the USA I performed as a guitarist with Collegium Musicum, the Contemporary Chamber Players, San Luis Obispo Chamber Orchestra, Harper Symphony, Kaia String Quartet, and CUBE Ensemble. My composition studies began at the Catholic University of Argentina in Buenos Aires with Roberto Caamaño, Marta Lambertini and Gerardo Gandini, in whose composition workshops outside the university I advanced my technique. It was in 1987 that I moved to Chicago, to pursue graduate studies in composition at the University of Chicago, studying with Ralph Shapey, Shulamit Ran, John Eaton and Howard Sandroff. My music has been performed by ensembles such as the Wiener KammerOrchester, Grant Park Festival Orchestra, Symphonic Orchestra of Michoacán, Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Fox Valley Symphony Orchestra, Civic Orchestra of Chicago, Pro Musica, Concertante di Chicago, Chicago Sinfonietta, Rembrandt Chamber Players, Avalon String Quartet, Spektral Quartet, Contemporary Chamber Players, CUBE Ensemble and Sonic Inertia. -

With Elbio Barilari Broadcast Schedule — Spring 2017

FIESTA! with Elbio Barilari Broadcast Schedule — Spring 2017 PROGRAM #: FST 17-01 RELEASE: April 2, 2017 Spanish Music and Visual Arts Spanish composers seem to have a strong predilection for the visual arts. One would say this is not surprising in a country that gave us Diego Velázquez, Goya and Picasso among many other first rate artists. Enrique Granados composed his monumental “Goyescas” (after Francisco Goya) in 1911, as a piano suite and in 1915 used its movements as the skeleton for his opera of the same title. In this program we present a selection of the original piano suite recorded by Cuban pianist Jorge Luis Prats. Goya also receives a tribute from Cuban born Spanish composer Eduardo Morales-Caso. The title of the piece, “Volavérunt”, refers to a 1799 painting by Goya from the series “Los Caprichos.” The meaning of the word is unknown and it was also the focus of an award-winning novel by the Uruguayan writer Antonio Larreta. Catalonian composer Xavier Montsalvatge pays tribute, an ironic tribute it may be said, to Salvador Dalí. His “Folia daliniana” alludes at the same time to the ancient tradition of the 16th century tradition of the “folias” and to the flashy surrealist painter of the famous moustache. Finally, three more Catalonians, Joan Saura, Nuno Rebello and Xavier Maristany, provide a miniature based on the contemporary graphics of the cartoons. This piece is part of a series of improvisations they did during the 1990s. Enrique Granados: Suite from Goyescas- Los requiebros, Coloquio la reja, Quejas o La maja y el ruisenor, El pelele (Jorge Luis Prats, piano) Decca 478 2732 Eduardo Morales-Caso: Volavérunt (Duo Sonidos) Verso VRS 2109 Xavier Montsalvatge: Folia daliniana (Perspectives Ensemble; Sato Moughalian, flute; Angel Gil-Ordoñez, conductor) Naxos 8.573101 Joan Saura/Nuno Rebello/ Xavier Maristany: Cartoons (Joan Saura, Nuno Rebello, Xavier Maristany: guitars, samplers, toys) NCM9 PROGRAM #: FST 17-02 RELEASE: April 9, 2017 Easter 2017 Latin America has developed its own and strong Easter musical traditions. -

Paradigm for Effective Pre-College Classical Guitar Methodology: a Case Study of Two Models of Effective Instruction Renthungo Merry

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-1-2010 Paradigm for effective pre-college classical guitar methodology: a case study of two models of effective instruction Renthungo Merry Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Merry, Renthungo, "Paradigm for effective pre-college classical guitar methodology: a case study of two models of effective instruction" (2010). Dissertations. Paper 212. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School A PARADIGM FOR EFFECTIVE PRE-COLLEGE CLASSICAL GUITAR METHODOLOGY: A CASE STUDY OF TWO MODELS OF EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTION A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Renthungo Merry College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music December 2010 © 2010 RENTHUNGO MERRY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED i ABSTRACT Merry, Renthungo. A Paradigm for Effective Pre-College Classical Guitar Methodology: A Case Study of Two Models of Effective Instruction. Doctor of Arts in Music Education dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, 2010. Many classical guitar teachers of the past had stated that the field of classical guitar education in general was an area that was in need of re-evaluation in terms of proper teaching methodology, especially at the beginner level. However, the last twenty years have seen the steady growth and expansion of classical guitar education. -

SELECTED REVIEWS “A First Rate Guitarist

Rua Fernandes Vieira, 634 / 1101 90035-090 - Porto Alegre, RS - Brazil Phone: +55 51 3311-4130 Mobile: +55 51 9965-0069 e-mail: [email protected] CURRICULUM One of Brazil’s most acclaimed and versatile musicians, Daniel Wolff is a Bachelor of Music from the Uruguayan University in Montevideo. Wolff was later awarded full scholarships from the Brazilian government to obtain the Master of Music and Doctor of Music degrees from New York’s prestigious Manhattan School of Music, where he was given the Helen Cohn Award for outstanding achievement. He became thus the first Brazilian to receive a doctorate in guitar performance. A Professor of Music at the Brazilian Federal University (UFRGS), where he created the Master and Doctor of Music Degrees in Guitar Performance, he is in constant demand to teach in universities and music festivals in the United States, Germany, Portugal, México, Colombia, Bolívia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. Daniel was also a Guest Professor at Berlin’s Universität der Künste. Winner of guitar competitions in Brazil and the United States, he has performed widely in Europe, South America and the United States, where he appeared at New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall. His main guitar teachers were Eduardo Fernández, Abel Carlevaro and Manuel Barrueco. As an arranger and composer, he had his works performed and recorded by orchestras and chamber ensembles in Europe and the Americas. His arrangements have been recorded by a variety of artists, culminating in a Grammy Award and twice the Açorianos Prize for best arranger. He has also written various prize-winning film scores and ballets; his ballet Quadressencias was released in DVD by the UCS Symphony Orchestra with the Caxias do Sul Dance Company. -

La Estabilización Articular En La Técnica De La Guitarra. El Papel De Abel Carlevaro

La estabilización articular en la técnica de la guitarra. El papel de Abel Carlevaro The articular stabilization in guitar technique. The role of Abel Carlevaro por Ricardo Barceló Abeijón CEHUM. Universidade do Minho, Portugal [email protected] La estabilización de las articulaciones corporales, acto también conocido como fijación, es una cons- tante en las múltiples acciones que realizamos en la vida cotidiana, habitualmente de forma instintiva e inconsciente. En la técnica guitarrística la fijación articular ha sido entendida normalmente como un recurso biomecánico que implica la estabilización firme, circunstancial y controlada, de una o más articulaciones corporales, en ocasiones de forma consciente y deliberada, en particular durante la fase de preparación de una obra musical. El guitarrista y pedagogo uruguayo Abel Carlevaro adoptó este concepto como uno de los pilares de su técnica instrumental. En este trabajo nos propusimos indagar, principalmente, acerca del origen del uso de las estabilizaciones articulares voluntarias en la técnica de la guitarra clásica y la hipotética influencia de los métodos con argumentación científica para la ense- ñanza del piano, publicados durante la primera mitad del siglo XX, tales como los de Otto Ortmann y Arnold Schultz. También investigamos los trabajos pedagógicos de los guitarristas Abel Carlevaro y Charles Duncan relacionados con esta temática, y el alcance que han tenido los mismos, con relación a la adopción de este concepto por la comunidad guitarrística internacional. Palabras clave: Estabilización, fijación, guitarra, piano, Carlevaro, biomecánica, pedagogía. The articular stabilization is an action known too as ‘fixation’ and it is quite common in the multiple actions that we carry out in everyday life, usually instinctively and unconsciously.