Curtis Symphony Orchestra Wednesday, February 5, 2020, 7:30 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARMAS JÄRNEFELT Symphonic Fantasy � Berceuse Serenade � Suite in E Flat Major Lahti Symphony Orchestra � Jaakko Kuusisto

BIS-CD-1753 ARMAS JÄRNEFELT Symphonic Fantasy � Berceuse Serenade � Suite in E flat major Lahti Symphony Orchestra � Jaakko Kuusisto Jaakko Kuusisto BIS-CD-1753_f-b.indd 1 10-09-09 15.50.26 JÄRNEFELT, Armas (1869–1958) 1 Symphonic Fantasy (1895) (Fennica Gehrman) 20'51 Suite in E flat major (1897) (Fennica Gehrman) 21'32 2 1. Andantino 4'53 3 2. Adagio quasi andante 6'42 4 3. Presto 3'11 5 4. Lento assai 2'55 6 5. Allegro feroce 3'48 Serenade (1893) (Fennica Gehrman) 29'55 7 1. Allegretto quasi marcia 4'24 8 2. Andante espressivo 7'48 9 3. Adagio 7'50 10 4. Allegretto 3'45 11 5. Sostenuto 1'57 12 6. Allegro vivace 3'59 13 Berceuse for violin and orchestra (1904) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 3'40 TT: 77'07 Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti) Jaakko Kuusisto conductor & solo violin 2 Armas Järnefelt: Orchestral Works ‘A very promising beginning’, wrote the critic of the journal Uusi Suometar when the Lyric Overture, the first orchestral work by Armas Järnefelt (1869–1958), was premièred in Helsinki in March 1892. This ‘promising begin - ning’ led to a distinguished career as a composer, during which Järnefelt pro - duced numerous orchestral works, music for the stage, solo and choral songs and more than ten cantatas. Nonetheless he is remembered primar ily as a con - ductor, in which capacity he was highly regarded and directed the Royal Opera in Stockholm for many years. Of course he was not the only composer whose production has been overshadowed by a performing career, but in his case the shadow is espe cially long and deep. -

Jean Sibelius Ursprijnglichekarrlia-Musik Isr Nichr Vdllig Sibelius Selbst Haufig Langere Fassungen Seiner ,,Historischen Erhalten

BIS-CD-9f5 STEREO lp p pl Total playingtime: 76'01 SIBELIUS, Johan (Jean)Julius Christian(r865-1e57) Karelia (1893)r,yr,r @ 50'00 KuvaelmamusiikkiaViipurilaisen Osakunnan Juhla Arpajaisiin Kansanvalistuksenhyviiksi Viipurin liiilnissii ScenicMusic for a Festivaland Lottery in Aid of Educationin the Provinceof Viipuri * Itemsnurkecl completedand reconstructedb.t, Kalet'i Aho (1997) E Overture [Altegro ntotlerato] - Pii lento - [Jn poco ntotlerato - 8'12 Moderato assai - Vit,ace E Tableau I Karjalainenkoti. Sanomasodasta (Vuosi 1293)/ 3'43 A Karelian home.News ol War ( 1293) 'Oi IAlla vito] - Piirlentct: Ukko ylijumala...' Heikki Laitinen. vocalpart I; Taito Hoffren. vocalparr II E Tableau 2 Viipurin linnan perustaminen(Vuosi 1293)/ 3'38 The tbunding of Viipuri Castle(1293) * Moder(ttoossai -Vivace Tableau 3 Liettuanherttua Narimont veronkannossaKiikisalmen liiiinissii 5'13 (Vuosi 1333)/ Narimont,the Duke of Lithuania,levvins taxes in the provinceof Kiikisalmi ( I 333) lll x Alle.qro urur,o l'26 tr Intemezzo [Il. Morierato 3'1j E Tableau ,l Kaarle KnuutinpoikaMipurin linnassa.Balladi (Vuosi lz146)/ 9'09 Karl Knutssonin Mipuri Castle.Ballade (1446) 'Hiill Tenpo di ntenuettonon troppo lento.Dansen i rosenlund: om en afion...' Raimo Laukka, baritone(soto hoilr Pertti Kuusrl Tableau 5 PontusDe la GardieKlikisalmen edustalla 1580 / 7,2q PontusDe la Gardieat rhe saresof Kiikisalmi in 1580 tr * Motlerato,mu n,,n lettto 3'14 tr Intermezzo[II]. Marsch nacheinem altenMotiv ('Tableau5rl:') 4'08 Alla marcia SIBELIUS!S TAR'LIA MUSIC the Russian standpoint'Old Finland') was adminisrratively - (jn Fahidn Dahlsil united with the rest ofFinland ( Neu Finland') in 1811.The Karelia. in the broadest senseot' the tenn the area inhabited country now became an aulonomous grand duchy ol the - by Karelian tribes can be divided into Easten Karelia (be- Russian empire, alrhough its ia!\-making powers and cultural tween Lake Ladoga and Ihe White Sea. -

SIBELIUS SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No. 76 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 76 (January 2015) - C ontent S - Page Editorial ....................................................................................... 3 News and Views .......................................................................... 5 Original Sibelius. Festival Review by Edward Clark .................. 6 Sibelius and Bruckner by Peter Frankland .................................. 10 The Piano Music of Jean Sibelius by Rudi Eastwood .................. 16 Why do we like Sibelius? by Edward Clark ................................ 19 Arthur Butterworth by Edward Clark .......................................... 20 A memoir of Tauno Hannikainen by Arthur Butterworth ............ 25 2014 Proms – Review by Edward Clark ...................................... 27 Sibelius. Thoughts by Fenella Humphries ................................... 30 The Backman Trio. Concert and CD review by Edward Clark ... 32 Finlandia. Commentary by David Bunney ................................... 33 The modernity of Sibelius by Edward Clark ............................... 36 Sibelius and his Violin Concerto by Edward Clark ..................... 38 The United Kingdom Sibelius Society would like to thank its corporate members for their generous support: ............................................................................................... BB-Shipping (Greenwich) Ltd Transfennica (UK) Ltd Music Sales Ltd Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken Breitkopf & Härtel - 2 - Editorial -

Orchestral Works He Had Played in His 35-Year Tenure in the Orchestra

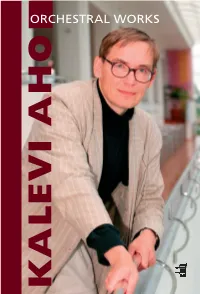

KALEVI AHO ORCHESTRAL WORKS KALEVI AHO – a composer of contrasts and surprises alevi Aho (born in Finland in 1949) possesses one of today’s most exciting creative voices. A composer with one foot in the past and one in the pres- K ent, he combines influences from the most disparate sources and transforms them through his creative and emotional filter into something quite unique. He does not believe in complexity simply for the sake of it. His music always communicates directly with the listener, being simultaneously ‘easy’ yet ‘difficult’, but never banal, over-intellectual, introvert or aloof. In his own words, “A composer should write all sorts of works, so that something will always evoke an echo in people in different life situations. Music should come to the help of people in distress or give them an ex- perience of beauty.” Kalevi Aho is equally natural and unaffected in his symphonies and operas as he is in his intimate musical miniatures. Monumental landscapes painted in broad brush- strokes go hand in hand with delicate watercolours, serious artistic confessions and humour. The spectrum of human emotions is always wide, and he never lets his lis- teners off lightly. He poses questions and sows the seeds of thoughts and impulses that continue to germinate long after the last note has died away. “His slightly unassuming yet always kind appearance is vaguely reminiscent of Shosta- kovich, while his musical voice, with its pluralistic conception of the world and its intricate balance between the deliberately banal and the subtle, is undoubtedly closer to late Mahler.” It is easy to agree with this anonymous opinion of Kalevi Aho. -

Harri Ahmas Symphony No. 1

Harri Ahmas Symphony No.1 Lahti Symphony Orchestra Okko Kamu AHMAS, Harri (b.1957) Symphony No.1 (2001–02) (Music Finland) 39'22 1 q = 54–56 11'45 2 q = 116–120 7'39 3 q = 48–50 – attacca – 8'13 4 h = 96 11'22 Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti) Okko Kamu conductor 2 Harri Ahmas: Symphony No.1 The Lahti-based composer and performing musician Harri Ahmas (b.1957) studied composition under Einar Englund and Einojuhani Rautavaara. Ahmas started piano lessons when he was ten, but seven years later changed to the bassoon. For most of the 1980s he was a member of the Finnish Radio Sym phony Orchestra, until he was appointed principal bassoonist of the Lahti Sym phony Orchestra in 1989. In addition to his orchestral work, Ahmas is an active chamber musician. As a com- poser his catalogue of works contains pieces in many different genres: over the years he has written not only three symphonies but also a number of concertos with orchestral accompaniment, orchestral works, works for wind band, a large amount of chamber music, two chamber operas, the score to the music play Itämaan tähti (Star of the East), the six-movement mass Kumartakaa valkeaa (Bow towards the Light) and various arrangements for orchestra, for example of hymns and folk songs. Many of Ahmas’s works have been written in response to commissions but, accord ing to the composer, the First Symphony was composed as the result of a need to write something just for himself, for a change. Ahmas has stated that in general his music does not have an ideological basis: ‘Most important of all are the emotional reactions that the listener has to the music. -

SIBELIUS, Johan (Jean) Christian Julius (1865-1957)

BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/12/04 10:04 AM Page 2 SIBELIUS, Johan (Jean) Christian Julius (1865-1957) 1 Snöfrid, Op. 29 (1900) (Wilhelm Hansen) 14'15 Improvisation for recitation, mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Viktor Rydberg Allegro molto – Andantino – Melodrama. Pesante – Andante (ma non troppo lento) Stina Ekblad narrator Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 2 Overture in A minor for orchestra, JS 144 (1902) (Fazer) 9'13 Andante molto sostenuto – Allegro – Tempo I Cantata for the Coronation of Nicholas II, JS 104 (1896) (Manuscript) 18'37 (Kantaatti ilo- ja onnentoivotusjuhlassa Marraskuun 2. päivänä 1896) for mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Paavo Cajander 3 I. Allegro. Terve nuori ruhtinas… 8'33 4 II. Allegro. Oikeuden varmassa turvassa… 9'58 Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 2 BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/12/04 10:04 AM Page 3 Rakastava, Op. 14 ( [1894]/1911-12) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 12'18 for string orchestra, timpani and triangle 5 I. The Lover. Andante con moto 4'06 6 II. The Path of His Beloved. Allegretto 2'26 7 III. Good Evening!… Farewell! Andantino – Doppio più lento – Lento assai 5'34 Jaakko Kuusisto violin • Ilkka Pälli cello 8 Oma maa (My Own Land), Op. 92 (1918) (Fazer) 13'26 for mixed chorus and orchestra Text: Kallio (Samuel Gustaf Bergh) Allegro molto moderato – Allegro moderato – Vivace (ma non troppo) – Molto tranquillo – Tranquillo assai – Moderato assai (e poco a poco più largamente) – Largamente assai Jubilate Choir (choral direction: Astrid Riska) 9 Andante festivo, JS 34b (1922/1938) for strings and timpani (Fazer) 5'10 TT: 74'48 Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti) (Leader: Jaakko Kuusisto) Osmo Vänskä conductor 3 BIS-CD-1265 Sib cantatas 7/5/04 10:31 AM Page 4 Snöfrid, Op. -

Winter 2015/2016

N N December 2015 January/February 2016 Volume 44, No. 2 Winter Orgy® Period N 95.3 FM Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition; Reiner, Chicago WHRB Program Guide Symphony Orchestra (RCA) Bach: Violin Concerto No. 1 in a, S. 1041; Schröder, Hogwood, Winter Orgy® Period, December, 2015 Academy of Ancient Music (Oiseau-Lyre) Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue; Katchen, Kertesz, London with highlights for January and February, 2016 Symphony Orchestra (London) Chopin: Waltzes, Op. 64; Alexeev (Seraphim) Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35; Staryk, Beecham, Wednesday, December 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (EMI) Strauss, J., Jr.: On the Beautiful Blue Danube, Op. 314; Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (DG) 6:45 pm HARVARD MEN’S BASKETBALL Tchaikovsky: Ouverture solennelle, 1812, Op. 49; Bernstein, Harvard at Northeastern. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (DG) 6:45 pm HARVARD MEN’S HOCKEY Harvard at Union. Thursday, December 3 10:00 pm BRIAN CHIPPENDALE (cont.) 10:00 pm BRIAN CHIPPENDALE Hailing from Providence, Rhode Island, drummer Brian Saturday, December 5 Chippendale has been churning out an endless wall of noise since the late 90s. Using a hand-painted and well-beaten drum 5:00 am PERDIDO EN EL SIGLO: A MANU CHAO kit, homemade masks equipped with contact mics, and an ORGY (cont.) array of effect and synthesizer pedals, his sound is powerful, 9:00 am HILLBILLY AT HARVARD relentless, and intensely unique. Best known for his work with 12:45 pm PRELUDE TO THE MET (time approximate) Brian Gibson as one half of noise-rock duo Lightning Bolt, 1:00 pm METROPOLITAN OPERA Chippendale also works with Matt Brinkman as Mindflayer and Puccini: La Bohème; Barbara Frittoli, Ana Maria solo as Black Pus. -

WEDNESDAY SERIES 7 Osmo Vänskä, Conductor Lilli

14.12. WEDNESDAY SERIES 7 Helsinki Music Centre at 19.00 Osmo Vänskä, conductor Lilli Paasikivi, mezzo-soprano Jussi Nikkilä, narrator Eero Hämeenniemi: Winter calm and Summer storms 20 min for mezzo-soprano and orchestra (fp, Yle commission) INTERVAL 20 min Jean Sibelius: The Tempest, selections by Osmo Vänskä 60 min Introduction Ariel flies in Ariel’s First Song Ariel’s Second Song Interlude The Oak Tree Ariel’s Third Song Interlude Interlude Humoresque Dance of the Shapes Melodrama The Shapes Dance Out Intermezzo Ariel flies in Ariel’s Fourth Song The Rainbow Melodrama Minuet Polka The Dogs Ariel brings the foes to Prospero Ariel’s Fifth Song Cortège Epilogue Interval at about 19:40. The concert ends at about 21:15. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and online at yle.fi/rso. 2 EERO HÄMEENNIEMI Eero Hämeenniemi emerged as the cially the Carnatic music of Southern voice of his classical-music generation India – not so much as a treasure in the late 1970s, as chairman of the trove of musical material or exotic ide- Korvat auki (Ears Open) association. as but as the generator of a new type He studied with Paavo Heininen at the of musicianship, attitude and commu- Sibelius Academy, graduating in com- nity. Another of his great interests is position in 1978 and thereafter contin- improvisation; this he has cultivated in uing his studies with Boguslaw Schäfer, his Nada ensemble, for example, and Franco Donatoni, Joseph Schwantner he has variously incorporated it in his and others. As a lecturer and later pro- compositions. fessor of composition at the Sibelius In the 2000s, Eero Hämeenniemi Academy, he has left his mark on con- has developed an even more pro- temporary Finnish music, since most of found relationship with Indian music, the young generation of Finnish com- as reflected in his many orchestral and posers have been his pupils. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA S I I E J O ZAW WENTY -FIFTH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 1 1 8th Season • 1 998-99 Bring your Steinway: With floor plans from acre gated community atop 2,100 to 5,000 square feet, prestigious Fisher Hill you can bring your Concert Jointly marketed by Sotheby's Grand to Longyear. International Realty and You'll be enjoying full-service, Hammond Residential Real Estate. single-floor condominium living at Priced from $1,100,000. its absolute finest, all harmoniously Call Hammond Real Estate at located on an extraordinary eight- (617) 731-4644, ext. 410. LONGYEAR at Ijrisner Jiill BROOKLINE ^fc. £P^&^ "*| < , fit ;ui'JK*MHM8il 1 .,, Si'v ; i^^S^^^^ LEU <p CORTLAND Hammond SOTHEBYS PROPERTIES INC RESIOENTIAL iTTTfuaiHTlTniTii I JtSfn PR f. S T A T F, • ' & .:'. I r i \ : . Seiji Ozawa, Music Director 25 TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Eighteenth Season, 1998-99 *\ Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. R. Willis Leith, Jr., Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Deborah B. Davis Edna S. Kalman Vincent M. O'Reilly Gabriella Beranek Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read James F. Cleary Nancy J. Fitzpatrick Mrs. August R. Meyer Hannah H. Schneider John F. Cogan, Jr. Charles K. Gifford, Richard P. Morse Thomas G. Sternberg Julian Cohen ex-officio Mrs. Robert B. Stephen R. Weiner William F. Connell Avram J. Goldberg Newman Margaret Williams- William M. -

Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland)

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Jean Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland) Born in Hämeenlinna, Häme Province. Slated for a career in law, he left the University of Helsingfors (now Helsinki) to study music at the Helsingfors Conservatory (now the Sibelius Academy). His teachers were Martin Wegelius for composition and Mitrofan Vasiliev and Hermann Csilag. Sibelius continued his education in Berlin studying counterpoint and fugue with Albert Becker and in Vienna for composition and orchestration with Robert Fuchs and Karl Goldmark. He initially aimed at being a violin virtuoso but composition soon displaced that earlier ambition and he went on to take his place as one of the world's greatest composer who not only had fame in his own time but whose music lives on without any abatement. He composed a vast amount of music in various genres from opera to keyboard pieces, but his orchestral music, especially his Symphonies, Violin Concerto, Tone Poems and Suites, have made his name synonymous with Finnish music. Much speculation and literature revolves around Sibelius so-called "Symphony No. 8." Whether he actually wrote it and destroyed it or never wrote it all seems less important than the fact that no such work now exists. Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 (1903-4, rev. 1905) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Sir Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Dvorák: Violin Concerto) PHILIPS ELOQUENCE 468144-2 (2000) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Sir Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra ( + 2 Humoresques and 4 Humoresques) AUSTRALIAN ELOQUENCE ELQ4825097 (2016) (original LP release: PHILIPS 9500 675) (1979 Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Mario Rossi/Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della Radiotelevisione Italiana (rec. -

A Comparative Analysis of the 1915 and 1919 Versions of Symphony

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE 1915 AND 1919 VERSIONS OF THE SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 82 BY JEAN SIBELIUS John Richard Norine, Jr. B.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Anshel Brusilow, Major Professor Cindy McTee, Minor Professor Clay Couturiaux, Committee Member Graham H. Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies Henry Gibbons, Chair, Division of Conducting and Ensembles James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Norine, Jr., John Richard. A Comparative Analysis of the 1915 and 1919 Versions of Symphony No. 5 in E-flat Major, op. 82 by Jean Sibelius. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 41 pp., 20 illustrations, references, 31 titles. The initial composition of the Fifth Symphony in E-flat Major, Op. 82 was undertaken as a commission to celebrate the composer's fiftieth birthday. Unhappy with the initial efforts, two revisions were then performed; the first was in 1916 and the final revision in 1919. Despite the larger form of the work seeming to have been changed between the 1915 and 1919 versions, the smaller gestures of thematic expression in both versions remained similar. On the surface, it had appeared that the composer had eliminated a movement, changing the 1919 version into a three movement form. This view was not challenged by the composer at the time, and since the earlier versions had either been withdrawn or destroyed, there was no way to compare the original efforts to the final product until recently. -

Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland)

FINNISH & BALTIC SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Jean Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland) Born in Hämeenlinna. Slated for a career in law, he left the University of Helsingfors (now Helsinki) to study music at the Helsingfors Conservatory (now the Sibelius Academy). His teachers were Martin Wegelius for composition and Mitrofan Vasiliev and Hermann Csilag. Sibelius continued his education in Berlin studying counterpoint and fugue with Albert Becker and in Vienna for composition and orchestration with Robert Fuchs and Karl Goldmark. He initially aimed at being a violin virtuoso but composition soon displaced that earlier ambition and he went on to take his place as one of the world's greatest composer who not only had fame in his own time but whose music lives on without any abatement. He composed a vast amount of music in various genres from opera to keyboard pieces, but his orchestral music, especially his Symphonies, Violin Concertos, Tone Poems and Suites, have made his name synonymous with Finnish music. Much speculation and literature revolves around Sibelius so- called "Symphony No. 8." Whether he actually wrote it and destroyed it or never wrote it all seems less important than the fact that no such work now exists. Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 (1899) Maurice Abravanel/Utah Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) MUSICAL CONCEPTS MC 132 (3 CDs) (2012) (original release: VANGUARD SRV 381-4 {4 LPs}) (1978) Nikolai Anosov/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra MELODIYA D 02952-3 (LP) (1956) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Philharmonia Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos.