Ace Metrix, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM OCTOBER 4TH 2018-1.Xlsx

CINEMA AUGUSTA PROGRAM COMING ATTRACTIONS BELOW or VISIT OUR WEB PAGE PHONE 86422466 TO CHECK SESSION TIMES www.cinemaaugusta.com MOVIE START END PAW PATROL MIGHTY PUPS (G) Oct 4th Thu PAW PATROL (G) 12.00pm 12.50pm Max Calinescu, Devan Cohen. SMALLFOOT (G) 1.00pm 2.40pm Our favourite pups are back with all new superpowers on CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (G) 2.50pm 4.40pm their biggest mission yet. VENOM (M) 4.50pm 6.50pm The House with Clock in Walls (PG) 7.00pm 8.40pm JOHNNY ENGLISH STRIKES AGAIN (PG) VENOM (M) 8.50pm 10.45pm Rowan Atkinson. After a cyber‐attack reveals the identity of all of the active Oct 5th Fri PAW PATROL (G) 10.30am 11.20am undercover agents in Britain, Johnny English is forced to come TEEN TITANS GO (PG) 11.30am 1.00pm out of retirement to find the mastermind hacker. The House with Clock in Walls (PG) 1.10pm 3.00pm THE MERGER (M) VENOM (M) 3.10pm 5.10pm Damian Callinan, John Howard, Kate Mulvany. SMALLFOOT (G) 5.20pm 7.00pm Troy Carrington, a former professional football player returns THE MERGER (M) 7.10pm 8.50pm to his country town after an abrupt end to his sporting career VENOM (M) 9.00pm 11.00pm and is persuaded to coach the hapless local footy team, the Roosters. Oct 6th Sat SMALL FOOT (G) 10.30am 12.10pm VENOM (M) VENOM (M) 12.20pm 2.20pm Tom Hardy, Michelle Williams. PAW PATROL (G) 2.30pm 3.20pm TEEN TITANS GO (PG) 3.30pm 5.00pm When Eddie Brock acquires the powers of a symbiote, he will CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (G) 5.10pm 7.00pm have to release his alter‐ego Venom to save his life. -

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

Jimmy James About

JIMMY JAMES ABOUT The ONE & MANY VOICES of JIMMY JAMES - LIVE! AWARD WINNING ENTERTAINER! Singer-Songwriter of the global dance hit "FASHIONISTA" topping the BILLBOARD Dance Charts with OVER 20 MILLION VIEWS on YouTube from fan-made videos (from the album 'JAMESTOWN' on iTunes & Amazon). Jimmy James has worked with some of the world's best dance music producers including Chris Cox, Barry Harris, The Berman Brothers, IIO, Eric Kupper, Thomas Gold and more...most of whom have also produced and remixed for Cher, Madonna, Britney Spears, Whitney Houston - to name a few. In addition to being a recording artist, Jimmy James is an Award-Winning Entertainer known for his lively stunning musical cabaret shows featuring his Live Legendary Vocal Impressions. James, an ever-evolving Performance Artist, carries the legacy of his past as the world's greatest Marilyn Monroe impersonator. Although he retired his Marilyn act in 1997, his visual illusion of her is still considered the best there ever was. He garnered numerous national television appearances on the most popular talk shows of the 80s and 90s. By 1996 he landed on a giant Billboard in the center of Times Square as Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland and Bette Davis with Supermodel Linda Evangelista. Additionally, his 1991 ad as Marilyn Monroe with horn-rimmed glasses for l.a. Eyeworks is passed "New York performance artist Jimmy James [song around the internet and copied repeatedly for tattoos and art galleries everywhere. The ad image shot by Greg Gorman may be THE most misidentified photo of Marilyn Fashionista] is so darn clever, it's hard not to offer Monroe ever. -

PETER LINDBERGH: the Unknown a Breathtaking Story in Photographs and an Innovative New Chapter in Fashion Photography

SCHIRMER/MOSEL VERLAG WIDENMAYERSTRASSE 16 • D-80538 MÜNCHEN TELEFON 089/21 26 70- 0 • TELEFAX 089/33 86 95 e - mail: press@schirmer- mosel.com Munich, March 2011 PRESS RELEASE PETER LINDBERGH: The Unknown A breathtaking story in photographs and an innovative new chapter in fashion photography Internationally-known German fashion photographer Peter Lindbergh was born in 1944 and grew up in Duisburg. During the eighties, he revolutionized his métier with his iconic images of Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Tatjana Patitz, Nadja Auermann and other supermodels. His photographs sought to capture the personality, character, and identity of the models — and not just the glitter and glamour. In doing so, Lindbergh laid the foundation for the “supermodel” phenomenon that swept the globe. Peter Lindbergh: Peter Lindbergh’s new project, The Unknown, represents yet another innovative The Unknown The Chinese Episode chapter in the field of fashion photography. His exhibition at the Ullens Center for With an Interview by Jérôme Sans Contemporary Art in Beijing (1 April through 22 May 2011) consists of huge murals 200 pages, 89 plates that are reproduced in our new photo book Peter Lindbergh: The Unknown. The Chinese ISBN 978-3-8296-0544-1 English edition with German Episode (200 pages, 89 plates). Lindbergh’s extraordinary images are displayed within supplement an unusual framework and from a novel perspective for fashion photography: The € 49.80; (A) 51.20; sFr 70.90 Unknown is a photographic “serial novel” of fashion shootings set against the backdrop of a fictitious landing of beings from outer space. Peter Lindbergh commenced this visual tour de force in 1990, and he has pursued it with cineastic intensity to the present day. -

5Th Annual President's Scholarship Gala

5th Annual President’s Scholarship Gala October 15, 2010 Oklahoma City, OK 7:00 PM LU Forever... Forever LU Distinguished Service Award Honorees Celebrity Host Dennis Haysbert Richard L. Sias Dennis Haysbert captured the attention of audiences and A graduate of Kansas University, Mr. Sias began his critics alike with his ground breaking role as President appreciation of the arts while earning his Bachelor’s degree in David Palmer on FOX’s hit series “24” for which he Romance Languages in 1951. In addition to his contributions to received his first Golden Globe Nomination. Haysbert higher education, Mr. Sias has been an instrumental leader in returned to television starring in his own series “THE the Oklahoma community as a strong supporter of the arts and UNIT” for CBS which premiered with record breaking scholarships. A 2002 inductee into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame, ratings. He is also known as the face and voice of Mr. Sias is very highly respected in the greater Oklahoma City Allstate Insurance. business community and has been integral in strengthening the relationship between Langston University and the corporate community. Barbara McKinzie A nationally-acclaimed CPA who holds an MBA from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, Ms. McKinzie owns the distinction of being the first to serve as the International Evening Entertainer President and Chief Administrative Officer for Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Ms. McKinzie has served as Deputy Director of Finance and Administration for Chicago’s Neighborhood Kelly Price Housing Services and as Comptroller for the Chicago Housing A native of Queens, New York, Mrs. -

King, Michael Patrick (B

King, Michael Patrick (b. 1954) by Craig Kaczorowski Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2014 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Writer, director, and producer Michael Patrick King has been creatively involved in such television series as the ground-breaking, gay-themed Will & Grace, and the glbtq- friendly shows Sex and the City and The Comeback, among others. Michael Patrick King. He was born on September 14, 1954, the only son among four children of a working- Video capture from a class, Irish-American family in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Among various other jobs, his YouTube video. father delivered coal, and his mother ran a Krispy Kreme donut shop. In a 2011 interview, King noted that he knew from an early age that he was "going to go into show business." Toward that goal, after graduating from a Scranton public high school, he applied to New York City's Juilliard School, one of the premier performing arts conservatories in the country. Unfortunately, his family could not afford Juilliard's high tuition, and King instead attended the more affordable Mercyhurst University, a Catholic liberal arts college in Erie, Pennsylvania. Mercyhurst had a small theater program at the time, which King later learned to appreciate, explaining that he received invaluable personal attention from the faculty and was allowed to explore and grow his talent at his own pace. However, he left college after three years without graduating, driven, he said, by a desire to move to New York and "make it as an actor." In New York, King worked multiple jobs, such as waiting on tables and unloading buses at night, while studying acting during the day at the famed Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute. -

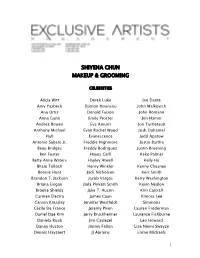

Shiyena Chun Makeup & Grooming

SHIYENA CHUN MAKEUP & GROOMING CELEBRITIES Alicia Witt Derek Luke Joe Dante Amy Yasbeck Djimon Hounsou John Malkovich Ana Ortiz Donald Faison John Romano Anna Gunn Emily Procter Jon Hamm Andrea Bowen Eva Amurri Jon Turtletaub Anthony Michael Evan Rachel Wood Josh Duhamel Hall Evanescence Judd Apatow Antonio Sabato Jr. Freddie Highmore Justin Bartha Beau Bridges Freddy Rodriguez Justin Bruening Ben Foster Hayes Carll Keke Palmer Betty Anne Waters Hayley Atwell Kelly Hu Bitsie Tulloch Henry Winkler Kenny Chesney Bonnie Hunt Jack Nicholson Kerr Smith Brandon T. Jackson Jacob Vargas Kerry Washington Briana Evigan Jada Pinkett Smith Kevin Nealon Brooke Shields Jake T. Austin Kim Cattrall Carmen Electra James Caan Kimora Lee Carson Kressley Jennifer Westfeldt Simmons Cécile De France Jeremy Piven Lauren Froderman Daniel Dae Kim Jerry Bruckheimer Laurence Fishburne Daniela Ruah Jim Caviezel Leo Howard Danny Huston Jimmy Fallon Lisa Niemi Swayze Dennis Haysbert JJ Abrams Lorne Michaels 1 Ludacris Paris Hilton Shawn Ashmore Maggie Grace Paul Giamatti Shoshana Bush Mark Feurstein Philip Seymour Tara Reid Marlee Matlin Hoffman Taye Diggs Meatloaf Randy Jackson Taylor Swift Michael C Hall Ray Winstone Terry Crews Michael Chiklis Rob Brown Todd Phillips Michael Ealy Romany Malco Tom Papa Mike Epps Rose Byrne Tony Shalhoub Mischa Barton Rose McGowan Tyrese Morgan Fairchild Ryan Eggold Vincent Cassel Muhammad Ali Rydaznrtist Virginia Madsen Nelsan Ellis Sam Rockwell Ziggy Marley Neve Campbell Samuel L. Jackson Zooey Deschanel Nikki Reed Sean Connery Nolan Sotillo Shaun White EDITORIAL AARP GQ Nylon Allure Harper's Bazaar OK Complex In Style People Cosmopolitan In Touch Teen Damsel Magazine L.A. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Bravo's Andy Cohen Throws a Live Party on Siriusxm to Celebrate Launch of His Memoir "Most Talkative"

Bravo's Andy Cohen Throws a Live Party on SiriusXM to Celebrate Launch of his Memoir "Most Talkative" Mark Consuelos to host 80s prom-themed special at SiriusXM studios in New York City with special guests and SiriusXM subscribers From his childhood days in St. Louis to crazy nights in the Bravo Clubhouse, Cohen tells all on "Andy Cohen is Most Talkative" NEW YORK, May 9, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) today announced that Bravo impresario Andy Cohen will celebrate the launch/publication of his new memoir MOST TALKATIVE: Stories from the Front Lines of Pop Culture with a live on-air 80s prom-themed party hosted by Mark Consuelos at SiriusXM studios in New York City. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO ) Voted "Most Talkative" in 1986 by his high school classmates, Cohen's moniker has stayed with him and guided him to where he is now. SiriusXM's "Andy Cohen is Most Talkative" special will air live on Tuesday, May 22 from 7:00 — 8:30 pm ET on SiriusXM Book Radio ch. 80. Encore presentations will air on May 23 at 9:30 pm on SiriusXM Book Radio, on May 24 at 10:00 am and 11:30 am and May 26 at 8:00 am and 9:30 am on SiriusXM Stars ch. 107, and on May 26 at 5:00 pm, May 27 at 9:00 pm and May 28 at 9:00 am on SiriusXM OutQ ch. 108 (all times ET). In front of an intimate, exclusive audience of SiriusXM subscribers, Cohen will share his personal story—from his childhood in St. -

Fiction and Documentary) Films On/In Africa (In Alphabetical Order, by Film Title

Marie Gibert [email protected] (Fiction and Documentary) Films on/in Africa (in alphabetical order, by film title) J. Huston (1951), The African Queen, starring Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Morley et al. A. Sissako (2006), Bamako, starring Aïssa Maïga, Tiécoura Traoré et al. C. Denis (1999), Beau Travail, starring Denis Lavant, Michel Subor, Grégoire Colin et al. R. Scott (2001), Black Hawk Down, starring Josh Hartnett, Eric Bana, Ewan McGregor et al. E. Zwick (2006), Blood Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Connelly, Djimon Hounsou et al. C. Denis (1988), Chocolat, starring François Cluzet, Isaach De Bankolé, Giulia Boschi et al. T. Michel (2005), Congo River, Beyond Darkness (documentary). F. Mereilles (2005), The Constant Gardener, starring Ralph Fiennes, Rachel Weisz, Hubert Koundé et al. B. Tavernier (1981), Coup de Torchon, starring Philippe Noiret, Isabelle Huppert, Jean-Pierre Marielle et al. R. Attenborough (1987), Cry Freedom, starring Denzel Washington, Kevin Kline, Penelope Wilton et al. S. Samura (2000), Cry Freetown (documentary). R. Bouchareb (2006), Days of Glory, starring Jamel Debbouze, Samy Naceri, Sami Bouajila et al. R. Stern and A. Sundberg (2007), The Devil Came on Horseback, starring Nicholas Kristof, Brian Steidle et al. S. Jacobs (2008), Disgrace, starring Eriq Ebouaney, Jessica Haines, John Malkovich et al. N. Blomkamp (2009), District Nine, starring Sharlto Copley, Jason Cope, David James et al. Z. Korda (1939), The Four Feathers, starring John Clements, June Duprez, Ralph Richardson et al. B. August (2007), Goodbye Bafana, starring Dennis Haysbert, Joseph Fiennes, Diane Kruger et al. T. George (2004), Hotel Rwanda, starring Don Cheadle, Sophie Okonedo, Joaquin Phoenix et al. -

Katya Thomas - CV

Katya Thomas - CV CELEBRITIES adam sandler josh hartnett adrien brody julia stiles al pacino julianne moore alan rickman justin theroux alicia silverstone katherine heigl amanda peet kathleen kennedy amber heard katie holmes andie macdowell keanu reeves andy garcia keira knightley anna friel keither sunderland anthony hopkins kenneth branagh antonio banderas kevin kline ashton kutcher kit harrington berenice marlohe kylie minogue bill pullman laura linney bridget fonda leonardo dicaprio brittany murphy leslie mann cameron diaz liam neeson catherine zeta jones liev schreiber celia imrie liv tyler chad michael murray liz hurley channing tatum lynn collins chris hemsworth madeleine stowe christina ricci marc forster clint eastwood matt bomer colin firth matt damon cuba gooding jnr matthew mcconaughey daisy ridley meg ryan dame judi dench mia wasikowska daniel craig michael douglas daniel day lewis mike myers daniel denise miranda richardson deborah ann woll morgan freeman ed harris naomi watts edward burns oliver stone edward norton orlando bloom edward zwick owen wilson emily browning patrick swayze emily mortimer paul giamatti emily watson rachel griffiths eric bana rachel weisz eva mendes ralph fiennes ewan mcgregor rebel wilson famke janssen richard gere geena davis rita watson george clooney robbie williams george lucas robert carlyle goldie hawn robert de niro gwyneth paltrow robert downey junior harrison ford robin williams heath ledger roger michell heather graham rooney mara helena bonham carter rumer willis hugh grant russell crowe -

Gigi Hadid Photographed by Helena Christensen Exclusively for the May 2019 Issue of Vogue Czechoslovakia

Gigi Hadid photographed by Helena Christensen exclusively for the May 2019 issue of Vogue Czechoslovakia The May issue of VOGUE CS features a photo shoot with one of the most sought after models in the world - Gigi Hadid. It is the first time Gigi has invited a magazine to her family farm located near New York. Helena Christensen, the Danish supermodel and icon of the nineties - who is also a successful photographer, shot the American model there for the Czechoslovak edition of the world‘s most important fashion magazine. Gigi wore clothes from several Czech fashion designers throughout the cover story. “I am delighted that thanks to the friendship of Eva Herzigova, Helena Christensen and Gigi Hadid, we could photograph Gigi in her secret place, where she has not yet invited any other photographer or jour- nalist. We tried to show Gigi as she’s never been seen before, with her horses, in a place she loves,” says Andrea Běhounková, Editor-in-Chief of Vogue CS. “I wanted her to be as much of herself as possible on her farm among horses, surrounded by nature. Gigi finds not only inspiration, but above all peace and security, in this environment. I wanted to capture her essence, the little girl that still remains in her. The wind blows in her hair, her eyes are full of expectations that something special will happen,” says Helena Christensen. Gigi Hadid personally invited Helena Christensen and the Vogue CS team to her farm located near New York which she shares with her mother and siblings. To capture the intimate and dreamlike atmosphere of the place, Helena Christensen combined digital photography with expired Polaroids.