Matatiele Road Rehabilitation Project Proposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information Document Basic Assessment

BACKGROUND INFORMATION DOCUMENT as part of the BASIC ASSESSMENT PROCESS for the PROPOSED DR08017 ROAD AND PORTAL CULVERT UPGRADE, MATATIELE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, ALFRED NZO DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 1. Introduction The Matatiele Local Municipality in conjunction with the Eastern Cape Department of Roads and Public Works has proposed the upgrade of the DR08017 Road from the R56 to Mvenyane Village. The project is located within Ward 21 of the Matatiele Local Municipality, Alfred Nzo District. Before construction of the pedestrian bridge may commence, an environmental authorisation is required from the Eastern Cape Department of Economic Development, Environmental Affairs and Tourism (EDEAT), in compliance with the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations of 2014. In order to obtain this authorisation a Basic Assessment is currently being undertaken by Enviroedge cc. 2. The Project The project is located in Ward 21. The start point, near Cedarville (0km) is from the intersection of the R56 and DR08017, and the end point (24km), is at Mvenyane Village. The proposed road upgrade involves the upgrading of the existing gravel road to a surfaced low-volume road, together with the upgrade of two watercourse crossings. The existing road is classified as a low volume road, however, this road has been identified as the most efficient link road between Mt Frere and Cedarville through to Matatiele. The road upgrade will offer the shortest route of surfaced road from Cedarville to Mt Frere (approximately 75km), compared to the current surfaced route via Kokstad (approximately 105km). The proposed road upgrade shall remain a single carriageway, two-way road. The DR08017 will be upgraded to Class 4 (6.8 metres wide), with a combination of sections including concrete pavement and bitumen. -

African Leafy Vegetables in South Africa

African leafy vegetables in South Africa WS Jansen van Rensburg1*, W van Averbeke2, R Slabbert2, M Faber3, P van Jaarsveld3, I van Heerden4, F Wenhold5 and A Oelofse6 1 Agricultural Research Council – Vegetable and Ornamental Plant Institute, Private Bag X293, Pretoria 0001, South Africa 2 Centre for Organic & Smallholder Agriculture, Department of Crop Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology, Private Bag X680, Pretoria 0001, South Africa 3 Medical Research Council, Nutrition Intervention Research Unit, Private Bag X19, Parow 7925, South Africa 4 Agricultural Research Council – ANAPI, Meat Industry Centre, Private Bag X2, Irene 0062, South Africa 5 University of Pretoria – Division of Human Nutrition, Faculty of Health Sciences, PO Box 667, Pretoria 0001, South Africa 6 University of Pretoria – Centre for Nutrition, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, Pretoria 0002, South Africa Abstract In this article the term ‘African leafy vegetables’ was adopted to refer to the collective of plant species which are used as leafy vegetables and which are referred to as morogor o imifinoy b African people in South Africa. Function is central in this indigenous concept, which is subject to spatial and temporal variability in terms of plant species that are included as a result of diversity in ecology, culinary repertoire and change over time. As a result, the concept embraces indigenous, indigenised and recently introduced leafy vegetable species but this article is concerned mainly with the indigenous and indigenised species. In South Africa, the collection of these two types of leafy vegetables from the wild, or from cultivated fields where some of them grow as weeds, has a long history that has been intimately linked to women and their traditional livelihood tasks. -

Eastern Eastern Cape Cape Flagstaff Sheriff Service Area Flagstaff Sheriff

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# ñ!.!C# # # # !C $ # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # ## # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ñ # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # ^ # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #^# !C #!C# # # # # # # # # $ # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C# ## # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # !C # # !C# # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ## # ñ# # # # # !C # # !C # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ### #!C # # !C # ## ## # # # !C # ## !C # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C# # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### #^ # # # # # # # # # # # #ñ# # ^ !C# # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # !C !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # !C# # # # # !C ## # !C # # ^$ # ## # # # !C# ^ # # !C # # !C ## # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # ñ ## # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ^ # ## # # -

ANNUAL REPORT 20 Contact: 043 711 9514 HUMAN SETTLEMENTS Customer Care Line: 086 000 0039 314 13

Eastern Cape Department of Human Settlements Steve Tshwete Building • 31-33 Phillip Frame Road Waverly Park • Chiselhurst • 5247 • East London ANNUAL REPORT 20 /20 Vote: 11 Contact: 043 711 9514 HUMAN SETTLEMENTS Customer Care Line: 086 000 0039 www.ecdhs.gov.za 13 14 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 /20 14 Vote: 11 ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2013/14 FINANCIAL YEAR VOTE 11: DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROVINCE OF EASTERN CAPE HUMAN SETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROVINCE OF EASTERN CAPE VOTE NO. 11 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 /20 14 FINANCIAL YEAR 1 ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2013/14 FINANCIAL YEAR VOTE 11: DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROVINCE OF EASTERN CAPE CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................ 5 1. DEPARTMENT GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................................... 6 2. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................. 7 3. FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER/MEC ............................................................................................................... 10 4. REPORT OF THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER ...................................................................................................... 12 5. STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY AND CONFIRMATION OF ACCURACY FOR THE ANNUAL REPORT ..................................................................................................................................... -

Lusikisiki Flagstaff and Port St Johns Sheriff Service Area

LLuussiikkiissiikkii FFllaaggssttaaffff aanndd PPoorrtt SStt JJoohhnnss SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa DUNDEE Mandela IZILANGWE Gubhethuka SP Alfred SP OLYMPUS E'MATYENI Gxako Ncome A Siqhingeni Sithinteni Sirhoqobeni Ngwegweni SP Mruleni SP Izilangwe SP DELHI Gangala SP Mjaja SP Thembeni SP MURCHISON PORT SHEPSTONE ^ Gxako Ntlabeni SP Mpoza SP Mqhekezweni DUNDEE REVENHILL LOT SE BETHEL PORT NGWENGWENI Manzane SP Nhlanza SP LONG VALLEY PENRITH Gxaku Matyeni A SP Mkhandlweni SP Mmangweni SP HOT VALE HIGHLANDS Mbotsha SP ñ Mgungundlovu SP Ngwekazana SP Mvubini Mnqwane Xhama SP Siphethu Mahlubini SP NEW VALLEYS BRASFORT FLATS N2 SHEPSTONE Makolonini SP Matyeni B SP Ndzongiseni SP Mshisweni SP Godloza NEW ALVON PADDOCK ^ Nyandezulu SP LK MAKAULA-KWAB Nongidi Ndunu SP ALFREDIA OSLO Mampondomiseni SP SP Qungebe Nkantolo SP Gwala SP SP Mlozane ST HELENA B Ngcozana SP Natala SP SP Ezingoleni NU Nsangwini SP DLUDLU Ndakeni Ngwetsheni SP Qanqu Ntsizwa BETSHWANA Ntamonde SP SP Madadiyela SP Bonga SP Bhadalala SP SP ENKANTOLO Mbobeni SP UMuziwabantu NU Mbeni SP ZUMMAT R61 Umzimvubu NU Natala BETSHWANA ^ LKN2 Nsimbini SP ST Singqezi SIDOI Dumsi SP Mahlubini SP ROUNDABOUT D eMabheleni SP R405 Sihlahleni SP Mhlotsheni SP Mount Ayliff Mbongweni Mdikiso SP Nqwelombaso SP IZINGOLWENI Mbeni SP Chancele SP ST Ndakeni B SP INSIZWA NESTAU GAMALAKHE ^ ROTENBERG Mlenze A SIDOI MNCEBA Mcithwa !. Ndzimakwe SP R394 Amantshangase Mount Zion SP Isisele B SP Hlomendlini SP Qukanca Malongwe SP FIKENI-MAXE SP1 ST Shobashobane SP OLDENSTADT Hibiscus Rode ñ Nositha Nkandla Sibhozweni SP Sugarbush SP A/a G SP Nikwe SP KwaShoba MARAH Coast NU LION Uvongo Mgcantsi SP RODE Ndunge SP OLDENSTADT SP Qukanca SP Njijini SP Ntsongweni SP Mzinto Dutyini SP MAXESIBENI Lundzwana SP NTSHANGASE Nomlacu Dindini A SP Mtamvuna SP SP PLEYEL VALLEY Cabazi SP SP Cingweni Goso SP Emdozingana Sigodadeni SP Sikhepheni Sp MNCEBA DUTYENI Amantshangase Ludeke (Section BIZANA IMBEZANA UPLANDS !. -

Technical Workshop 6 – Msunduzi Municipality

TECHNICAL WORKSHOP 6 – MSUNDUZI MUNICIPALITY Greater Edendale and Vulindlela Development Area 1. BACKGROUND The Msunduzi Municipality commonly known as Pietermaritzburg or the “City of Choice” is located along the N3 at a junction of an industrial corridor 80km inland from Durban on the major road route between the busiest harbour in Africa, and the national economic power houses of Johannesburg and Pretoria. The Msunduzi Municipality covers an area of 635 km² with an estimated population of 617,000 people. The city of Pietermaritzburg is located within the Msunduzi local municipal area, and is the second largest city within KwaZulu-Natal and the Capital City of the Province. Pietermaritzburg combines both style and vitality and is a vibrant city set in the breathtakingly beautiful KwaZulu-Natal Midlands region. Figure 1: Msunduzi City Perspective Seeped in history, the City is a cultural treasure- Source: Msunduzi Tourism Development Strategy trove brimming with diversity and colour. It has a profound and perplexing urban metamorphosis and few cities epitomize the vibrancy of a contemporary African city better than Pietermaritzburg. The city’s outlook portrays and seeks to create a memorable and highly imagable city which engenders a strong sense of ownership and pride and reflects the history, culture and achievements of the people of the City. 2 2. LOCATION MAP The city of Pietermaritzburg serves as a gateway to the inland economic heartland which offers uncapped economic opportunity and investment return potential. Its location has a strong influence on regional channels of investment, movement and structuring of the provincial spatial framework for growth and development. -

List of Outstanding Trc Beneficiaries

List of outstanding tRC benefiCiaRies JustiCe inVites tRC benefiCiaRies to CLaiM tHeiR finanCiaL RePaRations The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development invites individuals, who were declared eligible for reparation during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC), to claim their once-off payment of R30 000. These payments will be eff ected from the President Fund, which was established in accordance with the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act and regulations outlined by the President. According to the regulations the payment of the fi nal reparation is limited to persons who appeared before or made statements to the TRC and were declared eligible for reparations. It is important to note that as this process has been concluded, new applications will not be considered. In instance where the listed benefi ciary is deceased, the rightful next-of-kin are invited to apply for payment. In these cases, benefi ciaries should be aware that their relationship would need to be verifi ed to avoid unlawful payments. This call is part of government’s attempt to implement the approved TRC recommendations relating to the reparations of victims, which includes these once-off payments, medical benefi ts and other forms of social assistance, establishment of a task team to investigate the nearly 500 cases of missing persons and the prevention of future gross human rights violations and promotion of a fi rm human rights culture. In order to eff ectively implement these recommendations, the government established a dedicated TRC Unit in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which is intended to expedite the identifi cation and payment of suitable benefi ciaries. -

Kwazulu Natal Province 1

KWAZULU NATAL PROVINCE 1. PCO CODE 088 LADYSMITH (UKHAHLAMBA REGIONAL OFFICE) MP Edna Molewa (NEC member) Cell 082 964 1256 PLO Errol E Makoba Cell 082 601 8181 Email [email protected] Administrator Thulani Dlamini Cell 073 6791439 Physical Address Tribent Building 220 Murchison Street Ladysmith, 3370 Postal Address P.O. Box 3791, Ladysmith, 3370 Tel 036 635 4701 Fax 036 635 4685 E-mail [email protected] Ward 1-25(25) Municipality Emnambithi Region Ukhahlamba 2. PCO CODE 802 PHOENIX MP Trevor Bonhomme Cell 082 8700 673 Administrator Stanley Moonsamy Cell 072 140 9017 Physical Address Phoenix Community Centre 20 Feathersstone Place Whetsone Phoenix 4068 Postal Address P.O.Box 311, Mount Edgecom Place.Whestone Phoenix 4300 Tel 031 5071800 Fax 031 500 8575 E-mail [email protected]/[email protected] Ward 48-57 (9) Municipality Ethekwini Region Ethekwini 3. PCO CODE 803 Moses Mabhida Regional Office MP Jackson Mthembu (NEC member) Cell 082 370 8401 Administrator Mlungisi Zondi Cell 0839472453 Physical Address 163 Jabu Ndlovu Street, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 Postal Address P.O. Box 1443, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 Tel 033 345 2753 /0716975765 Fax 033 342 3149 E-mail [email protected]/[email protected] Ward 1-9(9) Municipality Msunduzi Region Moses Mabhida 4. PCO CODE 805 PORT SHEPSTONE REGIONAL OFFICE MP Joyce Moloi-Moropa (NEC member) Cell 082718 4050 MPL Nonzwakazi Swartbooi Cell 083 441 9993 Administrator Lindiwe Mzele Cell 0731703811 Tel 039 682 6148 Fax 039 682 6141 E-mail [email protected]/[email protected] 10 October 2014 1 Physical Address 1st Flr, No.1 City Insurance Bldng, 44Wooley Street, Port Shepstone, 4240 Postal Address P.O. -

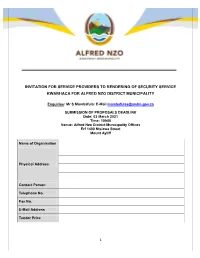

Bid Document Rendering of Security Service Kwabhaca

INVITATION FOR SERVICE PROVIDERS TO RENDERING OF SECURITY SERVICE KWABHACA FOR ALFRED NZO DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY Enquiries: Mr S Mambafula: E-Mail [email protected] SUBMISSION OF PROPOSALS DEADLINE Date: 03 March 2021 Time: 10h00 Venue: Alfred Nzo District Municipality Offices Erf 1400 Ntsizwa Street Mount Ayliff Name of Organisation Physical Address Contact Person Telephone No. Fax No. E-Mail Address Tender Price 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM NO. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. 1. Tender Advert 3 2. Checklist 4 3. Form of Offer and Acceptance 5 4. MBD 1 - Invitation to Bid 7 5. MBD 2 - Tax Clearance Certificate 8 6. MBD 4 - Declaration of Interest 9 7. MBD 5 - Declaration Procurement above R10 Million 11 8. MBD 6.1 - Preference Points Claim Form 12 9. MBD 8 - Past Supply Chain Practices 17 10. MBD 9 - Certificate of Independent Bid Declaration 19 11. Proof of Municipal Good Standing 22 12. Authority for Signatory 23 13. BEE Certificate 25 14. Banking Details 26 15. Joint Venture Agreement 27 16. Subcontractors Schedule 28 17. Experience of Tenderer 29 18. Assessment of Bidder 31 19. Record of Addenda Issued 32 20. Eligibility Criteria 33 21. Functionality Test 34 22. Company Profile 35 23. Central Supplier Database 36 24. Compulsory Briefing Session 37 25. Scope of Works 38 26. Pricing Structure 39 27. General Conditions of Tender 40 28. General Conditions of Contract 44 2 ALFRED NZO DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY ADVERT Alfred Nzo District Municipality (ANDM) is inviting all suitable Qualified and Experienced Professional Service Providers to submit bids for the following projects. The adjudication of the bids will be done in terms of Preferential Procurement Regulations, 2011 pertaining to Preferential Procurement Policy Framework (Act No5 of 2000) and will be based on the functionality and BBBEE points system. -

N2-Road Mount Frere Alfred Nzo District Municipality Umzimvubu Local Municipality Eastern Cape Province

N2-Road Mount Frere Alfred Nzo District Municipality Umzimvubu Local Municipality Eastern Cape Province September 2015 1 | P a g e Company Details (herein after referred to as Petrorex) Company Name DOTCOM TRADING 278 Trading as Petrorex Registration number CK 2008/008384/23 Members JL Pieterse Slogan “Energy in Motion” Official Logo Website www.petrorex.co.za Address 42 Bontebok crescent Theresaburg security village Thereseapark Pretoria Postal Address P O Box 52039 Dorandia 0188 Telephone number 012-542 1368 Hannes Pieterse 082 440 7969 e-mail [email protected] Dawie Pieterse 074 585 5085 e-mail [email protected] 2 | P a g e DOCUMENT DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Petrorex , with all reasonable skill, care and due diligence within the terms of the appointment with the client within the parameters specified in this document, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. No warranty or representation are made, either expressed or implied, with respect to fitness of use and no responsibility will be accepted by Petrorex or the authors for any losses, damages or claims of any kind, including, without limitation, direct, indirect, special, incidental, consequential or any other loss or damage that may arise from the use of the document This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. -

260307095952.Pdf

C o n t e n t s Introduction ......................... 4 Environmental and Disaster Management . 31 Aims of the Summit..................... 4 Aims of this document .................. 5 Comprehensive Primary Health Care...... 32 District Snapshot...................... 6 Food Security and Safety-Nets .......... 34 Economic Growth and Infrastructure . 10 Crime Management and Prevention ...... 36 Economic Growth ..................... 10 Institutional Capacity Building .......... 37 Infrastructure Development ............. 16 Provincial Infrastructure Expenditure Plans . 21 Service Delivery Mechanisms............ 38 National Government .................. 24 Conclusions ......................... 40 Unlocking Access to Land .............. 25 Glossary ........................... 41 Skills Development ................... 26 Spatial Development Planning .......... 29 Introduction A I M S O F T H E S ummi T Building on the results of the National Growth and Development The aim of the GDS is to reach broad agreement on: Summit (NGDS) in June 2003, government proposed that all • A development path and programme for the district. District and Metropolitan Municipalities hold Growth and • What each social partner (government, business, labour and Development Summits (GDS) in their area of jurisdiction. community sector) should contribute to the implementation of the programme? The summits should provide opportunities for building • Strengthening of strategic thrust of the district to ensure partnerships with social partners by bringing together planning -

Msunduzi Municipality Supplementary Valuation Roll 2018

MSUNDUZI MUNICIPALITY SUPPLEMENTARY VALUATION ROLL PREPARED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PROVISIONS OF THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT:- MUNICIPAL PROPERTY RATES ACT, 2004 (ACT 6 of 2004) CERTIFICATION BY MUNICIPAL VALUER AS CONTEMPLATED IN SECTION 34 ( g ) OF THE ACT I, Chazile Ndhlovu, registration number 6095, do certify that I have in accordance with the provisions of the Local GovernmenMunicipal Property Rates Act, 2004 (Act No. 6 of 2004), hereinafter referred to as the "Act", to the best of my skills and knowledge and without fear, favour or prejudice, prepared the Supplementary Valuation Roll for Msunduzi Municipality in terms of the provisions of the Act. In the discharge of my duties as municipal valuer I have complied with sections 43 and 44 of the Act. Certified at Pietermaritzburg on this 21st Day of May 2018 Professional Registration Number with the South African Council for the Property Valuers Profession: Category of Professional Registration: Registered Professional Valuer Signature of Municipal Valuer Total number of Freehold Properties on SV 5649 props Total valueof Freehold Properties on SV R 20,856,793,424 Total number of Sectional Title Properties on SV 1042 props Total valueof Freehold Properties on SV R 1,523,201,000 PART 1 PROPERTIES OTHER THAN SECTIONAL TITLE SCHEMES Erf Number Portion Allotment Township Owner Rates Category Street No Street Name Deeds Extent Market Value Effective Date S 78 Reason 885 276 FT MARY THRASH INDUSTRIAL R 301 80880 R 3,200,000 2017/07/01 78 (1) (g) Change of rates category 885 203 FT WINSTON STEYTLER RESIDENTIAL R 603 118269 R 2,500,000 2017/11/16 78 (1) (d) of which the market value has substantially increased or decreased for any reason after the last general valuation.