Merlin's People.Wps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Craig Y Merched

Crags of the Southern Rhinogydd Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ - All Rights Reserved Welsh Grit Selected Area Guides Craig y Merched An Interim Guide to Climbing By Dave Williams “Craig y Merched is a Welsh gritstone climbing mecca.” “Imbued with a delightful sense of isolation, this is a wonderful place to get away from it all” Steve Culverhouse in a fine position on Rhino’s Corner (VS 5a), a three star classic © DAVE WILLIAMS This 2019 Interim Guide is a comprehensive update of the previous Climbers’ Club Meirionnydd (2002) guidebook and may be used in conjunction with it www.steepstoneclimbing.co.uk Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ All Rights Reserved. The copyright owners’ exclusive rights extend to the making of electronic as well as physical 1 copies. No copying permitted in any form. Page Crags of the Southern Rhinogydd Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ - All Rights Reserved The Rhinogydd The Rhinogydd are a range of mountains located in Central Snowdonia, south of the Afon Dwyryd, east of Harlech, west of the A470 and north of the Afon Mawddach. Rhinogydd is the Welsh plural form of Rhinog, which means ‘threshold’. It is thought that the use of Rhinogydd derives from the names of two of the higher peaks in the range, namely Rhinog Fawr and Rhinog Fach. The Rhinogydd are notably rocky towards the central and northern end of the range, especially around Rhinog Fawr, Rhinog Fach and Moel Ysgyfarnogod. This area is littered with boulders, outcrops and large cliffs, all composed of perfect gritstone. The southern end of the range around Y Llethr and Diffwys has a softer, more rounded character, but this does not mean that there is an absence of climbable rock. -

Hill Walking & Mountaineering

Hill Walking & Mountaineering in Snowdonia Introduction The craggy heights of Snowdonia are justly regarded as the finest mountain range south of the Scottish Highlands. There is a different appeal to Snowdonia than, within the picturesque hills of, say, Cumbria, where cosy woodland seems to nestle in every valley and each hillside seems neatly manicured. Snowdonia’s hillsides are often rock strewn with deep rugged cwms biting into the flank of virtually every mountainside, sometimes converging from two directions to form soaring ridges which lead to lofty peaks. The proximity of the sea ensures that a fine day affords wonderful views, equally divided between the ever- changing seas and the serried ranks of mountains fading away into the distance. Eryri is the correct Welsh version of the area the English call Snowdonia; Yr Wyddfa is similarly the correct name for the summit of Snowdon, although Snowdon is often used to demarcate the whole massif around the summit. The mountains of Snowdonia stretch nearly fifty miles from the northern heights of the Carneddau, looming darkly over Conwy Bay, to the southern fringes of the Cadair Idris massif, overlooking the tranquil estuary of the Afon Dyfi and Cardigan Bay. From the western end of the Nantlle Ridge to the eastern borders of the Aran range is around twenty- five miles. Within this area lie nine distinct mountain groups containing a wealth of mountain walking possibilities, while just outside the National Park, the Rivals sit astride the Lleyn Peninsula and the Berwyns roll upwards to the east of Bala. The traditional bases of Llanberis, Bethesda, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed and Beddgelert serve the northern hills and in the south Barmouth, Dinas Mawddwy, Dolgellau, Tywyn, Machynlleth and Bala provide good locations for accessing the mountains. -

The Newsletter of the Gwydyr Mountain Club

THE GWYDYRNo35(Mar/Apr 2013) THE NEWSLETTER OF THE GWYDYR MOUNTAIN CLUB Richard Mercer, Neil Metcalfe, Geoff Brierley & Ronnie Davis on the wintry summit of Rhinog Fach. We’ve had an incredible past few weeks with winter re-arriving with a renewed ferocity and leaving us with some great memories of days out on the hill I make no apologies for the number of photographs in the newsletter but we’ve been exceptionally lucky and people have emailed me many pictures of their days out. For those not on facebook you may not have seen them before. Firstly apologies to Geoff but I appear to have lost your email article from the last issue (blame Microsoft bud as hotmail became outlook express and I’ve lost loads !) John Simpson went up to Scotland on the 2nd March and so it seems as good a point as any to get the newsletter going, thanks for the following John................................... We Travelled up to Callakille, 8 miles north of Applecross along the coast road on the 2nd March. We Spent the week in a cottage on the cliff top which looked out towards the Island of Rona & Isle of Raasay. All the high hills had a quite a bit of snow covering the tops though luckily all the roads were clear. We spent a number of days taking short cliff top walks. Including Callakille to Applecross & Lower Diabaig to Craig bothy. Mid week we decided to head to Loch Mhic Fhearchair behind Beinn Eighe. Didn't see any other living thing for the whole day :-) We did spot a golden eagle the day before while heading to Lower Diabaig, and at the same time what looked like 2 buzzards flying high over the loch. -

Adroddiad Asesiad Rheoliadau Cynefinoedd

Papur Cefndir: Adroddiad Asesiad Rheoliadau Cynefinoedd Cynllun Datblygu Lleol Gwynedd & Môn Chwefror 2015 Cynllun Datblygu Lleol ar y Cyd wedi’i Adneuo Cyngor Sir Ynys M ôn a Chyngor Gwynedd AS ESIAD RHEOLIADAU CYNEFINOEDD Chwefror 2015 ASESIAD RHEOLIADAU CYNEFINOEDD Cynllun Datblygu Lleol ar y Cyd wedi’i Adneuo Cyngor Sir Ynys Môn a Chyngor Gwynedd Paratowyd ar gyfer : Cyngor Sir Ynys M ôn a Chyngor Gwynedd dyddiad: Chwefror 2015 paratowyd ar Cyngor Sir Ynys M ôn a Chyngor Gwynedd gyfer: paratowyd Cheryl Beattie Enfusion gan: Alastair Peattie sicrwydd Alastair Peattie Enfusion ansawdd: Treenwood House Rowden Lane Bradford on Avon BA15 2AU t: 01225 867112 www.enfusion.co.uk Adroddiad Sgrinio ARhC Môn a Gwynedd Cynllun Datblygu Lleol ar y Cyd (CDLlaC) CYNNWYS TUD CRYNODEB GWEITHREDOL ........................................................................... 1 1.0 CYFLWYNIAD 1 Cefndir ............................................................................................................... 1 Ymgynghoriad .................................................................................................. 2 Pwrpas a Strwythur yr Adroddiad .................................................................. 2 2.0 ASESIAD RHEOLIADAU CYNEFINOEDD (ARhC) A'R CYNLLUN ..................... 3 Y Gofyn am Asesiad Rheoliadau Cynefinoedd .......................................... 3 Arweiniad ac Arfer Da .................................................................................... 3 3.0 ARhC CAM 1: SGRINIO ................................................................................ -

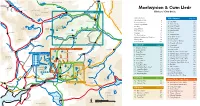

Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr

Llanrwst Llyn Padarn Llyn Ogwen CARNEDDAU Llanberis A5 Llyn Peris B5427 Tryfan Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr A4086 Nant Peris GLYDERAU B5106 Glyder Fach Capel Curig CWM LLEDR MAP PAGE 123 Climbers’ Club Guide Glyder Fawr LLANBERIS PASS A4086 Llynnau Llugwy Mymbyr Introduction A470 Y Moelwynion page 123 The Climbers’ Club 4 Betws-y-Coed Acknowledgments 5 20 Stile Wall 123 B5113 21 Craig Fychan 123 13 Using this guidebook 6 6 Grading 7 22 Craig Wrysgan 123 Carnedd 12 Carnedd Moel-siabod 5 9 10 23 Upper Wrysgan 123 SNOWDON Crag Selector 8 Llyn Llydaw y Cribau 11 3 4 Flora & Fauna 10 24 Moel yr Hydd 123 A470 A5 Rhyd-Ddu Geology 14 25 Pinacl 123 Dolwyddelan Lledr Conwy The Slate Industry 18 26 Waterfall Slab 123 Llyn Gwynant 2 History of Moelwynion Climbing 20 27 Clogwyn yr Oen 123 1 Pentre 8 B4406 28 Carreg Keith 123 Yr Aran -bont Koselig Hour 28 Plas Gwynant Index of Climbs 000 29 Sleep Dancer Buttress 123 7 Penmachno A498 30 Clogwyn y Bustach 123 Cwm Lledr page 30 31 Craig Fach 123 A4085 Bwlch y Gorddinan (Crimea Pass) 1 Clogwyn yr Adar 32 32 Craig Newydd 123 Llyn Dinas MANOD & The TOWN QUARRIES MAP PAGE 123 Machno Ysbyty Ifan 2 Craig y Tonnau 36 33 Craig Stwlan 123 Beddgelert 44 34 Moelwyn Bach Summit Cliffs 123 Moel Penamnen 3 Craig Ddu 38 Y MOELWYNION MAP PAGE 123 35 Moelwyn Bach Summit Quarry 123 Carrog 4 Craig Ystumiau 44 24 29 Cnicht 47 36 Moelwyn Bach Summit Nose 123 Moel Hebog 5 Lone Buttress 48 43 46 B4407 25 30 41 Pen y Bedw Conwy 37 Moelwyn Bach Craig Ysgafn 123 42 Blaenau Ffestiniog 6 Daear Ddu 49 26 31 40 38 38 Craig Llyn Cwm Orthin -

Views in North Wales, from Original Drawings

^%f^ •fopolg in JJorfS Valr* Views in North Wales ORIGINAL DRAWINGS BY T. L ROWBOTHAM Jrtlj;rolof[ic;i( ( historical, ^mtud, aitb Jlcstriptibc Botes COMPILED DY THE REV. W. J. LOFTIE, B.A., F.S.A. SCRIBNER, WELFORD, & ARMSTRONG, BROADWAY LONDON: MARCUS WARD & CO. 1875 J CONTENTS, Snowdon, ........ 9 Cader Idris, ....... 31 Conway Castle, . .43 Moel Siabod, ....... 66 Caernarvon Castle, . .79 1!i;dim;elert, ....... 103 CHROMOGRAPHS. Snowdon, ...... Frontispiece. Cader Idris, from the Barmouth Road, ... 30 Conway Castle, . .42 Moel Siabod, from Bettws-y-Coed, .... 67 Caernarvon Castle, . .78 Beddgelert, . .102 INITIAL VIGNETTES. Snowdon, ........ 9 Bridge near Corwen, . 31 Conway Castle, . • . .43 Cromlech—Plas Newydd, Anglesea, .... 66 Harlech Castle, . .79 Pillar of Eliseg, near Valle Crucis, .... 103 S NO IV DO N. JT^HE highest mountain in England and Wales, Snowdon yet falls far short of Ben Nevis and Ben Muich Dhui across the Scottish border. Indeed, there are as many as sixteen or seventeen Caledonian peaks which exceed it, some of them by as much as eight hundred feet. On the other I i.iikL there is no mountain in Ireland which approaches Snowdon by more than a hundred feet—Carrantuohill, in Kerry, the highest in the sister island, being only three thousand four hundred and fourteen, while Snowdon is three thousand five hundred and seventy-one feet above the waters of the intervening channel. This advantage is> moreover, set off by the position of the minor hills which surround Snowdon. Several of them, although of great altitude, arc at a sufficient distance not to interfere with him ; and while it is often difficult to say, in Highland or in Irish scenery, which is really the tallest in a chain of hills, there can never be a moment's doubt in the presence of Snowdon as to his supremacy among his compeers. -

Rock Trails Snowdonia

CHAPTER 6 Snowdon’s Ice Age The period between the end of the Caledonian mountain-building episode, about 400 million years ago, and the start of the Ice Ages, in much more recent times, has left little record in central Snowdonia of what happened during those intervening aeons. For some of that time central Snowdonia was above sea level. During those periods a lot of material would have been eroded away, millimetre by millimetre, year by year, for millions of years, reducing the Alpine or Himalayan-sized mountains of the Caledonides range to a few hardened stumps, the mountains we see today. There were further tectonic events elsewhere on the earth which affected Snowdonia, such as the collision of Africa and Europe, but with much less far-reaching consequences. We can assume that central Snowdonia was also almost certainly under sea level at other times. During these periods new sedimentary rocks would have been laid down. However, if this did happen, there is no evidence to show it that it did and any rocks that were laid down have been entirely eroded away. For example, many geologists believe that the whole of Britain must have been below sea level during the era known as the ‘Cretaceous’ (from 145 million until 60 million years ago). This was the period during which the chalk for- mations were laid down and which today crop out in much of southern and eastern Britain. The present theory assumes that chalk was laid down over the whole of Britain and that it has been entirely eroded away from all those areas where older rocks are exposed, including central Snowdonia. -

Habitat Regulations Assessment of Revised Draft Water Resources Management Plan 2013 – Assessment of Preferred Options

Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council Deposit Joint Local Development Plan HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT February 2016 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council Deposit Joint Local Development Plan Prepared for: Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council date: February 2016 prepared for: Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council prepared by: Cheryl Beattie Enfusion Alastair Peattie quality Alastair Peattie Enfusion assurance: Treenwood House Rowden Lane Bradford on Avon BA15 2AU t: 01225 867112 www.enfusion.co.uk HRA Report Anglesey and Gwynedd Deposit JLDP CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 Background 1 Consultation 2 Purpose and Structure of the Report 2 2.0 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT (HRA) AND THE PLAN 3 Requirement for Habitats Regulations Assessment 3 Guidance and Good Practice 3 3.0 HRA STAGE 1: SCREENING 5 Screening of the Preferred Strategy (2013) 5 Screening of the Deposit JLDP (2015) 6 Screening of the Focused Changes (2016) 23 4.0 HRA CONCLUSIONS 25 HRA Summary 25 APPENDICES I European Site Characterisations II Plans, Programmes and Projects Review III Screening of Deposit JLDP Screening Matrix IV HRA Consultation Responses 221/A&G JLDP Feb 2016 Enfusion HRA Report Anglesey and Gwynedd Deposit JLDP 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Anglesey County Council and Gwynedd Council are currently preparing a Joint Local Development Plan (JLDP) for the Gwynedd and Anglesey Local Planning Authority Areas. The JLDP will set out the strategy for development and land use in Anglesey and Gwynedd for the next 15 years (2011- 2026). It will set out policies to implement the strategy and provide guidance on the location of new houses, employment opportunities and leisure and community facilities. -

MOUNTAIN RESCUE TEAM LOG BOOK from 22Nd OCTOBER 58

MOUNTAIN RESCUE TEAM LOG BOOK FROM 22nd OCTOBER 58 TO 27th MARCH 60 1 NOTES 1 This Diary was transcribed by Dr. A. S. G. Jones between February and July, 2014 2 He has attempted to follow, as closely as possible, the lay-out of the actual entries in the Diary. 3 The first entry in this diary is dated 22nd October 1958. The last entry is dated 27th March, 1960 4 There is considerable variation in spellings. He has attempted to follow the actual spelling in the Diary even where the Spell Checker has highlighted a word as incorrect. 5 The spelling of place names is a very variable feast as is the use of initial capital letters. He has attempted to follow the actual spellings in the Diary 6 Where there is uncertainty as to a word, its has been shown in italics 7 Where words or parts of words have been crossed out (corrected) they are shown with a strike through. 8 The diary is in a S.O.Book 445. 9 It was apparent that the entries were written by number of different people 10 Sincere thanks to Alister Haveron for a detailed proof reading of the text. Any mistakes are the fault of Dr. A. S. G. Jones. 2 INDEX of CALL OUTS to CRASHED AIRCRAFT Date Time Group & Place Height Map Ref Aircraft Time missing Remarks Pages Month Type finding November 58 101500Z N of Snowdon ? ? ? False alarm 8 May 1959 191230Z Tal y Fan 1900' 721722 Anson 18 hrs 76 INDEX of CALL OUTS to CIVILIAN CLIMBING ACCIDENTS Date Time Group & Place Map Time Names Remarks Pages Month reference spent 1958 November 020745Z Clogwyn du'r Arddu 7 hrs Bryan MAYES benighted 4 Jill SUTTON -

Paul Gannon 2Nd Edition

2nd Edition In the first half of the book Paul discusses the mountain formation Paul Gannon is a science and of central Snowdonia. The second half of the book details technology writer. He is author Snowdonia seventeen walks, some easy, some more challenging, which bear Snowdonia of the Rock Trails series and other books including the widely evidence of the story told so far. A HILLWalker’s guide TO THE GEOLOGY & SCENERY praised account of the birth of the Walk #1 Snowdon The origins of the magnificent scenery of Snowdonia explained, and a guide to some electronic computer during the Walk #2 Glyder Fawr & Twll Du great walks which reveal the grand story of the creation of such a landscape. Second World War, Colossus: Bletchley Park’s Greatest Secret. Walk #3 Glyder Fach Continental plates collide; volcanoes burst through the earth’s crust; great flows of ash He also organises walks for hillwalkers interested in finding out Walk #4 Tryfan and molten rock pour into the sea; rock is strained to the point of catastrophic collapse; 2nd Edition more about the geology and scenery of upland areas. Walk #5 Y Carneddau and ancient glaciers scour the land. Left behind are clues to these awesome events, the (www.landscape-walks.co.uk) Walk #6 Elidir Fawr small details will not escape you, all around are signs, underfoot and up close. Press comments about this series: Rock Trails Snowdonia Walk #7 Carnedd y Cribau 1 Paul leads you on a series of seventeen walks on and around Snowdon, including the Snowdon LLYN CWMFFYNNON “… you’ll be surprised at how much you’ve missed over the years.” Start / Finish Walk #8 Northern Glyderau Cwms A FON NANT PERIS A4086 Carneddau, the Glyders and Tryfan, Nant Gwynant, Llanberis Pass and Cadair Idris. -

Moelwyns Moelwyns Snowdonia Snowdonia West West Snowdonia Snowdonia South South Winter Winter Snowdonia Snowdonia 223

Skills Snowdon Glyders Carneddau Moelwyns Snowdonia West Snowdonia South Winter Snowdonia 223 Moel - looking towards the Crimea Pass. Photo: Karl Midlane Karl Photo: the Crimea Pass. - looking towards p.228 (Hard) - (Hard) Amazing walking in the Moelwyns. The view from peak 672m, on the extension of the peak 672m, on the extension from The view in the Moelwyns. Amazing walking Horseshoe Meirch Skills Moelwyns Skills Snowdon Snowdon Glyders Glyders Carneddau Carneddau Moelwyns Moelwyns West Snowdonia West West Snowdonia West South Snowdonia South Snowdonia Snowdonia Winter Snowdonia Snowdonia Winter Snowdonia 222 Skills Snowdon Glyders Carneddau Moelwyns West Snowdonia South Snowdonia Snowdonia Winter 224 Moelwyns Area Overview Area Overview Moelwyns 225 Nant Peris Capel Curig Unlike its northern neighbours, the Y Foel Goch Moel A4086 Glyder Fawr (805m) A5 Moelwyns is more of a place for (1001m) 2 Skills Cynghorion hillwalkers looking to escape the crowds (674m) A4086 1 without the more demanding nature of Skills Pen y Gwryd From Pen y Pass Betws- the Carneddau. It really is a pleasant Moel Siabod y-Coed place to explore, with rugged, undulating (872m) and complex moorland terrain being the Snowdon 3 4 A498 theme. Solid navigation skills are required (1085m) Pont-y-pant Snowdon Gwynant 9 as some of the paths aren't that obvious Valley Carnedd y Lliwedd to follow. The best peaks are Moel Cribau (591m) (898m) 5 Dolwyddelan Siabod and Cnicht, although the other Snowdon Yr Aran routes in this section are mostly walks. p.74 8 (747m) Snowdon There is one isolated semi-scramble - Bertheos Moel Siabod via the South Ridge - and Craig Wen Yr Arddu A470 (587m) (589m) the infamous Fisherman's Gorge near Glyders Y Ro Wen Moel Meirch Crimea Dolwyddelan. -

Rhinog Fach Circuit

QMD Walks Rhinog Fach Circuit Copyright Bill Fear 2018 Relevant OS Maps include: OS Explorer OL18 (1:25), OS Landranger 124 (1:50), Harvey Rhinogs Superwalker (1:25), Harvey Snowdonia South XT40 (1:40). Demanding in places with some steep ascents/descents which can be slippery when wet. Can be extended into a long day by continuing onto Rhinog Fawr and back. Bit of a long boggy walk either in our out depending on which way you do it. I’ve put the walk in rather than out. Great campsite at Cae Adda SH691353. Small. Quiet. Great location. Distance: 12 miles (using footpath descent off Rhinog Fach) Going: Demanding. Some rough ground. Boggy in places. PRoW and FPs not always clear. Route finding necessary. 1. Park at CP on Graigddu Isaf road SH684302. Follow PRoW then TL at big JNCT SH674285 (still in forestry commission) onto forestry road to OA boundary at SH680278. TR to wall JNCT and after 200m TL along wall CB 145 to 407m ring contour SH682270. Continue to next wall JNCT and TR to 400m ring contour with crags SH681266. From here descend to track following rough CB 185. Continue to clear track at ruin SH678257 heading for Hafod y Brenhin SH676249, CB 200. 2. From Hafod y Brenhin follow PRoW on forestry track to where FP starts at SH679232, CB 280, at wall/fence JNCT. Follow path up to Diffwys summit SH661233. NOTE: FP goes to 688m ring contour and you need to TL to go up Diffwys, CB 228; alternative is to choose suitable point of departure from FP and route find up Diffwys.