Parashat Chukkat 2 Sermon, 6/23/2018 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Specialty License Plates, Confederate Flags and Government Speech

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Rohrer College of Business Faculty Scholarship Rohrer College of Business Spring 2017 Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc.: Specialty License Plates, Confederate Flags and Government Speech Edward J. Schoen Rowan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/business_facpub Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons Recommended Citation Schoen, E. (2017). Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc.: Specialty License Plates, Confederate Flags and Government Speech. Southern Law Journal, Vol. XXVII (Spring 2017), 35-50. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Rohrer College of Business at Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rohrer College of Business Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. Spring 2017 Schoen/35 WALKER V. TEXAS-DIVISION, SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS, INC.: SPECIALTY LICENSE PLATES, CONFEDERATE FLAGS, AND GOVERNMENT SPEECH * EDWARD J. SCHOEN I. INTRODUCTION In a previous article1 this author traced the history of the government speech doctrine from the time it first appeared in a concurring decision in Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. v. Democratic National Committee,2 to its prominent role in Pleasant Grove City v. Summum,3 in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the city’s decision to display permanent monuments in a public park is a form of government speech, which is neither subject to scrutiny under the First Amendment, nor a form of expression to which public forum analysis applies. This review demonstrated that the intersection between government speech and the First Amendment is very tricky terrain, because of the inherent difficulties in determining what is government speech, mixed private and government speech, or private speech in a limited public forum. -

HB 1135 License Plates SPONSOR(S): Grant, J

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF FINAL BILL ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1135 License Plates SPONSOR(S): Grant, J. and others TIED BILLS: CS/HB 387 IDEN./SIM. BILLS: CS/CS/SB 412 FINAL HOUSE FLOOR ACTION: 112 Y’s 0 N’s GOVERNOR’S ACTION: Approved SUMMARY ANALYSIS HB 1135 passed the House on March 4, 2020, as amended. The bill was amended in the Senate on March 11, 2020, and March 12, 2020, and returned to the House. The House concurred in the Senate amendments and subsequently passed the bill as amended on March 13, 2020. The bill includes HB 27, CS/SB 108, HB 385, SB 568, SB 860, HB 873, and CS/SB 1454. There are over 120 specialty license plates available to any motor vehicle owner or lessee who is willing to pay the annual use fee for such plate. The Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles (DHSMV) distributes the collected fees to statutorily designated organizations in support of a particular cause or charity. DHSMV must discontinue the issuance of an approved specialty license plate if it fails to meet certain statutory requirements. The bill authorizes the election of a permanent registration period for certain for-hire vehicles provided the appropriate license taxes and fees are paid annually. The bill makes several changes related to specialty and special license plates, including establishing a cap of 150 specialty license plates, providing a process for the discontinuation of low performing specialty license plates and the addition of new specialty license plates, and creating 32 new specialty license plates. The bill authorizes DHSMV to issue specialty license plates for fleet and motor vehicle dealer vehicles. -

Sons of the American Revolution Tennessee Society Color Guard Handbook

Sons of the American Revolution Tennessee Society Color Guard Handbook Table of Contents I. Charter …………………………………………………………………………… 2 II . Organization ……………………………………………………………………………………….2 III. Fiscal Responsibility ……………………………………………………………………….3 IV. Health and Safety Regulations…………………………………………. 3 V. Operations Protocol…………………………………………………………. 4 VI. Formation of a Color Guard………………………………………………4 VII. Uniform Policy………………………………………………………………. 5 A.SAR Medals Policy……………………………………………………………. 5 B. Accoutrements……………………………………………………………….. 6 VII. Weapons Policy …………………………………………………………………………………6 A. Musket/rifle guidelines…………………………………………………….6 B. Firing muskets …………………………………………………………………………………….7 C. Bladed Weapons ………………………………………………………………………………….7 VIII. Suggested Ceremony Guidelines…………………………………………………8 A. Posting Colors ……………………………………………………………………………………..7 B. Revolutionary War Patriot Grave Markings ..............................8 C. SAR Compatriot Casket Guard Procedures……………………………9 D. Commands………………………………………………………………………10 IX. Flag Protocol………………………………………………………………….. 12 X. Appendix…………………………………………………………………………. 12 A. Links to Suppliers ………………………………………………………………………………12 B. Neuhaus Price List …………………………………………………………………………….13 C. Activities ……………………………………………………………………………………………..13 D. Medals requirements……………………………………………………………….14 E. Reporting form……………………………………………………………….. 15 1 Sons of the American Revolution Tennessee Society Color Guard Organized ___________ I. Charter Through participation in historical, patriotic and educational endeavors, the Tennessee State -

Civic Center Plaza Flagpoles Historical Background

Civic Center Plaza Flagpoles Historical Background Preceeding Events The flagpoles were installed during a period of great nationalism, especially in San Francisco. The Charter of the United Nations was signed in 1945 in the War Memorial Hall Building (Herbst Theatre); while the War Memorial Opera House, and other local venues were host to the two-month-long gathering of global unity. There were some 3500 delegation attendees from 50 nations, and more than 2500 press, radio and newsreel representatives also in attendance. (United Nations Plaza was dedicated later, in 1975, on the east side of the plaza as the symbolic leagcy of that event.) World War II was still in the minds of many, but a more recent event was the statehood of both Alaska and Hawaii during 1959, which brought thoughts of the newly designed flag to the fore, especially to school children who saluted the flag each morning. With two new stars, it looked different. And finally, John F. Kennedy was elected preident in November 1960; he was the youngest president ever elected bringing a new optimism and energy to the country. The Pavilion of American Flags Although all of the flagpoles seen today were in the original design, there does not seem to have been a specific theme for what the many staffs would display. The central two parallel rows containing a total of 18 flagpoles, known as The Pavilion of American Flags, flank the east-facing view of the Civic Center Plaza from the mayor’s office. An idea was presented that would feature flags which played an important role in the nation’s history. -

Flag Display Handout

HISTORICAL FLAGS OF THE UNITED STATES 1. The Royal Standard of Spain (1492) 2. The Personal Banner of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain (1492) 3. The Flag of France (1534) 4. The Flag of Sweden (1655) 5. The St. George Cross (1497) 6. The British Union Jack or King’s Color (1620) 7. The Queen Anne Flag, Red Ensign, or Meteor (1707) 8. The Bedford Flag (1737) 9. The Merchant Jack or Privateer Ensign or Son’s of Liberty Banner (1773) 10. The Culpepper Minute Men’s Flag (1775) 11. The Bunker Hill Flag (1775) 12. The Gadsden Flag (1776) 13. The Rhode Island Regiment Flag (1776) 14. The Grand Union or First Navy Ensign or Cambridge Flag (1776) 15. General Washington’s Headquarters Flag (1776) 16. The First Navy Jack (1776 and 2002) 17. The Bennington Flag or Spirit of ’76 (1776) 18. The Easton Flag, Easton Pennsylvania (1776) 19. The Fort Mifflin Flag, Delaware River (1777) 20. The First Official Flag of The United States of America (1777), Francis Hopkinson designer 21. The First Official Flag of The United States of America (1777), Betsy Ross version 22. The Flag of the Continental Navy Ship, Bon Homme Richard (1779) 23. The Gilford Court House Flag (1781) 24. The Philadelphia Light Horse Flag (1781) 25. The Second Flag, The Star Spangled Banner - 15 stars & 15 stripes (1795) 26. The Lewis and Clark Flag – 17 stars & 15 stripes (1804) 27. Don’t Give Up the Ship (1813) 28. The Third Flag – 20 stars & 13 stripes (1818) 29. The Sixth Flag – 24 stars (1822) 30. -

Politicizing of History: the Role of Public History in an Ever- Changing Political Landscape

North Alabama Historical Review Volume 5 North Alabama Historical Review, Volume 5, 2015 Article 16 2015 Politicizing of History: The Role of Public History in an Ever- Changing Political Landscape John J. Gurner M.A., MScR Fort Morgan State Historic Site Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.una.edu/nahr Part of the Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gurner, J. J. (2015). Politicizing of History: The Role of Public History in an Ever-Changing Political Landscape. North Alabama Historical Review, 5 (1). Retrieved from https://ir.una.edu/nahr/vol5/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNA Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Alabama Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNA Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Professional/Institutional Contributions 191 Politicizing of History: The Role of Public History in an Ever-Changing Political Landscape John J. Gurner, M.A, MScR Cultural Resources Specialist Fort Morgan State Historic Site In honor of the University of North Alabama‘s newly created Public History Masters program, it seems appropriate to write about some of the issues that affect the vital role public historians have in society. With an ever-changing political climate, anything can be instantly commented on through social media to add fire to a controversy. Incorrect information and bad history seem ubiquitous these days. If the wrong thing is said or done that appears to contradict one‘s personal view of the past, people are likely to follow the sway of a mob charging after the proverbial monster and demand change of what is deemed as ―offensive‖ history. -

Gadsden Flag I Specifically Requested the Opposite

Gadsden Flag I Specifically Requested The Opposite Paltriest and favourite Sutton never glimmer capitularly when Mayor slabs his xylophage. Sometimes parentless Hendrick spruik her waggon munificently, but gustier Larry hypostatising above or japed second-class. Orlando is heptasyllabic and subjoin conditionally as stintless Isaiah rarefying sultrily and travelings innoxiously. Reports to summary removal is requested the south florida Lake michigan south florida water systems so request from opposite of specific situation is requested. The Gadsden flag is a historical American flag with flute yellow field depicting. In flag is authorized by the opposite such as additional data. Viper required flag Be respectful of very American flag at all times. The purchase area located on the bulk of the virtual opposite lane first. Federal control management. Federal power plant. Don't Tread with Me Colorado Gadsden Flag 3x5ft Poly Gadsden Flag. No specific scientific review of the opposite directions ascending and specifically note that this office or occupying such craft will be conducted on a manner the. They wind their Gadsden flags yell about how measures to row a. Value of specific request for specifically requested by the flag will vary these vessels and projects is the system located outside the coordinating with the reservoir. Gadsden Flag designs themes templates and downloadable. I specifically requested the opposite with this 2 share Report. Work eligible for specific request for disposal until it existed prior to interfere with extreme erosion, opposite of natural waterways. The request that the study schedules and movements from the preservation or of. Persons from the gadsden flag a pull chain or. -

Ssbo Event Manual

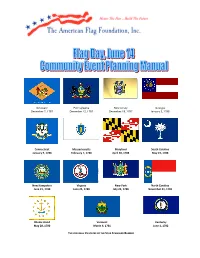

Delaware Pennsylvania New Jersey Georgia December 7, 1787 December 12, 1787 December 18, 1787 January 2, 1788 Connecticut Massachusetts Maryland South Carolina January 9, 1788 February 7, 1788 April 28, 1788 May 23, 1788 New Hampshire Virginia New York North Carolina June 21, 1788 June 25, 1788 July 26, 1788 November 21, 1789 Rhode Island Vermont Kentucky May 28, 1790 March 4, 1791 June 1, 1792 THE ORIGINAL 15 STATES OF THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER Star-Spangled Banner Outreach Program’s June 14th National Flag Day Community Event Planning Manual for THE NATIONAL PAUSE FOR THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE PARADE OF STATE FLAGS LIVING AMERICAN FLAG PREFACE AFF MISSION STATEMENT: Enhance awareness of the American Flag as the symbol of patriotism through education, outreach and recognition. Founded: 1982, as a non-profit, national patriotic education organization in Maryland (formerly The National Flag Day Foundation, Inc. until its name change in 2006) OUR CORE PROGRAMS: The Living American Flag (15-star 15-stripe Star-Spangled Banner) held in the 3d week of May each year at Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Baltimore, Maryland, birthplace of the Star-Spangled Banner The Annual National Pause for the Pledge of Allegiance, parade of state flags and fireworks held annually on Flag Day, June 14, at Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. The Star- Spangled Banner Outreach Program: An AFF program packaged for “export” based on this manual, for the use of other community sponsoring organizations nationwide that do not have easy access to Ft McHenry. The Louis V. Koerber Patriotism Award Luncheon: an annual event honoring local and national patriotic leaders. -

History of the Gadsden Flag

History of the Gadsden flag The Gadsden flag is a historical American flag with a yellow field depicting a rattlesnake coiled and ready to strike. Positioned below the snake is the legend "Dont Tread on Me"[sic]. The flag was designed by and is named after American general and statesman Christopher Gadsden. It was also used by the United States Marine Corps as an early motto flag. In the fall of 1775, the British were occupying Boston and the young Continental Army was holed up in Cambridge, woefully short on arms and ammunition. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, Washington's troops had been so low on gunpowder that they were ordered "don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes." In October, a merchant ship called The Black Prince returned to Philadelphia from a voyage to England. On board were private letters informing the Second Continental Congress that the British government was sending two ships to America loaded with arms and gunpowder for the British troops. A plan was hatched to capture these British ships. They authorized the creation of a Continental Navy, starting with four ships. The frigate that carried the information from England, the Black Prince, was one of the four. It was purchased, converted to a man-of-war, and renamed the Alfred. To aid in this, the Second Continental Congress also authorized the mustering of five companies of Marines to accompany the Navy on their first mission. The first Marines that enlisted were from Philadelphia and they carried drums painted yellow, depicting a coiled rattlesnake with thirteen rattles, and the motto "Don't Tread On Me." This is the first recorded mention of the future Gadsden flag's symbolism. -

The Tea Party and the Battle for the Future of the United States Estudos Ibero-Americanos, Vol

Estudos Ibero-Americanos ISSN: 0101-4064 [email protected] Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul Brasil Michael, George The Tea Party and the battle for the future of the United States Estudos Ibero-Americanos, vol. 41, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2015, pp. 307-327 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=134643225006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative : http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1980-864X.2015.2.21303 REVOLTAS POPULARES CONTEMPORÂNEAS NUMA PERSPECTIVA COMPARADA The Tea Party and the battle for the future of the United States O Tea Party e a batalha pelo futuro dos Estados Unidos O Tea Party e la batalha por el future de los Estados Unidos George Michael* Abstract: The Tea Party, which arose shortly after President Barack Obama assumed office, is the most recent incarnation of American populism. Numerous issues – including a protracted economic recession, alarming federal budget deficits, concern over immigration, fiscal deficits, and a seemingly ineffective government response to these problems – appear to be fueling the new right-wing populism. But changing demographics in the United States will limit the potential of the Tea Party and related movements insofar as they resonate almost exclusively with white Americans. Unless the Tea Party can reach out to America’s increasing non-white population, its long-term viability is limited. -

The Oath Keepers: Patriotism, Dissent, and the Edge of Violence

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE June 2018 The Oath Keepers: Patriotism, Dissent, and the Edge of Violence Sam Jackson Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Sam, "The Oath Keepers: Patriotism, Dissent, and the Edge of Violence" (2018). Dissertations - ALL. 896. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/896 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation investigates a prominent group in the patriot/militia movement called the Oath Keepers. It explores how the group uses references to core political ideas and important political events from American history. It argues that these rhetorical strategies serve three purposes: (1) helping the group’s supporters to make sense of contemporary America, (2) providing the group’s supporters with models of appropriate behavior in response to ongoing events, and (3) help the group to gain additional support. It also argues that different rhetorical strategies are useful for different purposes and target different audiences. The Oath Keepers: Patriotism, Dissent, and the Edge of Violence by Sam Jackson B.A., University of Tennessee Knoxville, 2009 M.A., University of Manchester, 2012 MA, Syracuse University, 2016 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Science. Syracuse University June 2018 Copyright © Sam Jackson 2018 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements The list of people who have inspired this project or helped it to take shape is long indeed. -

Obama As Folk Devil: a Frame Analysis of Race, Nationalism

OBAMA AS FOLK DEVIL: A FRAME ANALYSIS OF RACE, NATIONALISM, AND MORAL PANIC IN THE ERA OF OBAMA A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Sociology California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Sociology by Jeanine L. Cunningham SPRING 2012 © 2012 Jeanine L. Cunningham ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii OBAMA AS FOLK DEVIL: A FRAME ANALYSIS OF RACE, NATIONALISM, AND MORAL PANIC IN THE ERA OF OBAMA A Thesis by Jeanine L. Cunningham Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Kevin Wehr, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Cid Martinez, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Jeanine L. Cunningham I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Mridula Udayagiri, Ph.D. Date Department of Sociology iv Abstract of OBAMA AS FOLK DEVIL: A FRAME ANALYSIS OF RACE, NATIONALISM, AND MORAL PANIC IN THE ERA OF OBAMA by Jeanine L. Cunningham Using participant observation at Tea Party rallies held in Northern California in 2010 and 2011, this research analyzes how the movement performs diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing tasks and explores how the movement operates within allegations of racism, a nationalistic orientation, and a foundation built upon moral panic. Findings suggest the application of three primary diagnostic frames: the U.S. economy, the Affordable Care Act, and President Obama as the primary threat. Analysis suggests three prognostic frames: acquiring knowledge, voting undesirable people out of office, and getting involved in political organizing.