"Human Intestinal and Mul Tivisceral Transplantation"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laparoscopy As a Diagnostic Tool in Ascites of Unknown Origin: a Retrospective Study Conducted at Kasturba Hospital, Manipal

Research Article Open Access J Surg Volume 8 Issue 3 - March 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Chetan R Kulkarni DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2018.08.555740 Laparoscopy as a Diagnostic Tool in Ascites of Unknown Origin: A Retrospective Study Conducted at Kasturba Hospital, Manipal Chetan R Kulkarni1*, Badareesh Laxminarayan2 and Annappa Kudva3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Kasturba Hospital, Manipal 2Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Kasturba Hospital, Manipal 3Professor, Department of Surgery, Kasturba Hospital, Manipal Received: February 16, 2018; Published: March 01, 2018 *Corresponding author: Chetan R Kulkarni, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Kasturba Hospital, Manipal, India. Tel: 9535974395;Email: Abstract Background: Laparoscopy as a minimally invasive technique has long played an important role in the evaluation of ascites. Methods: A retrospective analysis was carried out on the record of 80patients who underwent laparoscopy after appropriate investigations had failed to reveal the cause of ascites. Results: Tuberculous peritonitis was reported in 46(57%), malignancies in 18(25%), cirrhosis in 4(5%) and peritonitis of unknown etiology in 8(10%)Conclusion: of patients. Two (2.5%) patients had complications, an Ileal perforation and in other Incisional hernia. Keywords: Ascites;Laparoscopy Diagnostic was Laparoscopy able to diagnose the pathology in 72 (90%) patients with ascites of unknown origin. Introduction Laparoscopy, as a minimally invasive technique has developed rapidly in recent years. Endoscopic examination of conventional laboratory examinations (including ascitic fluid cell count, albumin level, total protein level, Gram stain, culture who termed it as “Celioscopy” [1,2]. The term ‘ascites’ refers to and cytology ) as well as after imaging investigations (including peritoneal cavity was first attempted in 1901 by George Kelling Materialultrasound andand CT Methods scan). -

Routine Use of Feeding Jejunostomy in Pancreaticoduodenectomuy: A

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 95 JuneSeptember 2020 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202006.0114.v1 doi:10.20944/preprints202006.0114.v2 Routine use of Feeding Jejunostomy in Pancreaticoduodenectomuy: A Metaanalysis. DR.Bhavin Vasavada Consultant HepatoPancreaticobiliary and Liver Transplant Surgeon, Shalby Hospitals, Ahmedabad. Email: [email protected] Dr.Hardik Patel Consultant HepatoPancreaticobiliary and Liver Transplant Surgeon, Shalby Hospitals, Ahmedabad. Conflict of Interests: none. Funding disclosure: none. Abbreviations: Post operative pancreatic fistula (POPF), total parentral nutrition (TPN), Surgical site infections. (SSI) Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; feeding jejunostomy; morbidity; mortality Abstract: Aims and objectives: The primary aim of our study was to evaluate morbidity and mortality following feeding jejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy compared to the control group. We © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 95 JuneSeptember 2020 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202006.0114.v1 doi:10.20944/preprints202006.0114.v2 also evaluated individual complications like delayed gastric emptying, post operative pancreatic fistula, superficial and deep surgical site infection. We also looked for time to start oral nutrition and requirement of total parentral nutrition. Material and Methods: The study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and MOOSE guidelines. [9,10]. We searched pubmed, cochrane library, embase, google scholar with keywords like “feeding jejunostomy in pancreaticodudenectomy”, “entral nutrition in pancreaticoduodenectomy, “total parentral nutrition in pancreaticoduodenectomy’, “morbidity and mortality following pancreaticoduodenectomy”. Two independent authors extracted the data (B.V and H.P). The meta-analysis was conducted using Open meta-analysis software. -

Laparoscopic Truncal Vagotomy and Gatrojejunostomy for Pyloric Stenosis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE pISSN 2234-778X •eISSN 2234-5248 J Minim Invasive Surg 2015;18(2):48-52 Journal of Minimally Invasive Surgery Laparoscopic Truncal Vagotomy and Gatrojejunostomy for Pyloric Stenosis Jung-Wook Suh, M.D.1, Ye Seob Jee, M.D., Ph.D.1,2 Department of Surgery, 1Dankook University Hospital, 2Dankook University School of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea Purpose: Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) remains one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases and Received January 27, 2015 an important target for surgical treatment. Laparoscopy applies to most surgical procedures; however Revised 1st March 9, 2015 its use in elective peptic ulcer surgery, particularly in cases of pyloric stenosis, has not been popular. 2nd March 28, 2015 The aim of this study was to describe the role of laparoscopic surgery and an easily performed Accepted April 20, 2015 procedure for pyloric stenosis. We accordingly performed laparoscopic truncal vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy in 10 consecutive patients with pyloric stenosis. Corresponding author Ye Seob Jee Methods: Data were collected prospectively from all patients who underwent laparoscopic truncal Department of Surgery, Dankook vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy from August 2009 to May 2014 and reviewed retrospectively. University Hospital, Dankook Results: A total of 10 patients underwent laparoscopic trucal vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy for University School of Medicine, 119, peptic ulcer obstruction from August 2009 to May 2014 in ○○ university hospital. The mean age was Dandae-ro, Dongnam-gu, Cheonan 62.6 (±16.4) years old and mean BMI was 19.3 (±2.5) kg/m2. There were no conversions to open 330-714, Korea surgery and no occurrence of intra-operative complications. -

16. Questions and Answers

16. Questions and Answers 1. Which of the following is not associated with esophageal webs? A. Plummer-Vinson syndrome B. Epidermolysis bullosa C. Lupus D. Psoriasis E. Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2. An 11 year old boy complains that occasionally a bite of hotdog “gives mild pressing pain in his chest” and that “it takes a while before he can take another bite.” If it happens again, he discards the hotdog but sometimes he can finish it. The most helpful diagnostic information would come from A. Family history of Schatzki rings B. Eosinophil counts C. UGI D. Time-phased MRI E. Technetium 99 salivagram 3. 12 year old boy previously healthy with one-month history of difficulty swallowing both solid and liquids. He sometimes complains food is getting stuck in his retrosternal area after swallowing. His weight decreased approximately 5% from last year. He denies vomiting, choking, gagging, drooling, pain during swallowing or retrosternal pain. His physical examination is normal. What would be the appropriate next investigation to perform in this patient? A. Upper Endoscopy B. Upper GI contrast study C. Esophageal manometry D. Modified Barium Swallow (MBS) E. Direct laryngoscopy 4. A 12 year old male presents to the ER after a recent episode of emesis. The parents are concerned because undigested food 3 days old was in his vomit. He admits to a sensation of food and liquids “sticking” in his chest for the past 4 months, as he points to the upper middle chest. Parents relate a 10 lb (4.5 Kg) weight loss over the past 3 months. -

Recurrent Pneumothorax Following Abdominal Paracentesis

Postgrad Med J (1990) 66, 319 - 320 © The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1990 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.66.774.319 on 1 April 1990. Downloaded from Recurrent pneumothorax following abdominal paracentesis P.J. Stafford Department ofMedicine, Newham General Hospital, Glen Road, Plaistow, London E13, UK. Summary: A 62 year old man presented with abdominal ascites, without pleural effusion, due to peritoneal mesothelioma. He had chronic obstructive airways disease and a past history of right upper lobectomy for tuberculosis. On two occasions abdominal paracentesis was followed within 72 hours by pneumothorax. This previously unreported complication of abdominal paracentesis may be due to increased diaphragmatic excursion following the procedure and should be considered in patients with preexisting lung disease. Introduction Abdominal paracentesis is a widely used palliative right iliac fossa. Approximately 4 litres of turbid therapy for malignant ascites and is generally fluid was drained over 72 hours. The protein accepted as a procedure with few adverse effects: concentration was 46 g/l and microbiology and pneumothorax is not a recognized complication. I cytology were not diagnostic. Laparoscopy re- report a patient with recurrent pneumothorax vealed matted loops of bowel with widespread apparently precipitated by abdominal paracen- peritoneal seedlings. Histological examination of copyright. tesis. these lesions showed malignant mesothelioma of the epithelioid type. The patient suffered a left pneumothorax within Case report 48 hours ofparacentesis (before laparoscopy). This was treated with intercostal underwater drainage A 62 year old civil servant presented with a 6-week but recurred on two attempts to remove the drain, history ofworsening abdominal distension. -

Chronic Pancreatitis: What the Clinician Want to Know from Mri

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Magn Reson Manuscript Author Imaging Clin Manuscript Author N Am. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 August 01. Published in final edited form as: Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2018 August ; 26(3): 451–461. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2018.03.012. CHRONIC PANCREATITIS: WHAT THE CLINICIAN WANT TO KNOW FROM MRI TEMEL TIRKES, M.D. Department of Radiology and Clinical Sciences, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202, USA Keywords Pancreas; Chronic Pancreatitis; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography; Computerized Tomography INTRODUCTION Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a low prevalence disease.1–3 In 2006, there were approximately 50 cases of definite CP per 100,000 population in Olmsted County, MN 3, translating to a total of 150,000–200,000 cases in the US population. Clinical features of CP are highly variable and include minimal, or no symptoms of debilitating pain repeated episodes of acute pancreatitis, pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency and pancreatic cancer. CP profoundly affects the quality of life, which can be worse than other chronic conditions and cancers.4 Natural history studies for CP originated mainly from centers outside the U.S.5−910,11 conducted during the 1960–1990’s and consisted primarily of males with alcoholic CP. Only one large retrospective longitudinal cohort study has been conducted in the US for patients seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1976–1982.12 While these data provide general insights into disease evolution, it is difficult to predict the probability of outcomes or disease progression in individual patients. -

Information for Patients Having a Sigmoid Colectomy

Patient information – Pre-operative Assessment Clinic Information for patients having a sigmoid colectomy This leaflet will explain what will happen when you come to the hospital for your operation. It is important that you understand what to expect and feel able to take an active role in your treatment. Your surgeon will have already discussed your treatment with you and will give advice about what to do when you get home. What is a sigmoid colectomy? This operation involves removing the sigmoid colon, which lies on the left side of your abdominal cavity (tummy). We would then normally join the remaining left colon to the top of the rectum (the ‘storage’ organ of the bowel). The lines on the attached diagram show the piece of bowel being removed. This operation is done with you asleep (general anaesthetic). The operation not only removes the bowel containing the tumour but also removes the draining lymph glands from this part of the bowel. This is sent to the pathologists who will then analyse each bit of the bowel and the lymph glands in detail under the microscope. This operation can often be completed in a ‘keyhole’ manner, which means less trauma to the abdominal muscles, as the biggest wound is the one to remove the bowel from the abdomen. Sometimes, this is not possible, in which case the same operation is done through a bigger incision in the abdominal wall – this is called an ‘open’ operation. It does take longer to recover with an open operation but, if it is necessary, it is the safest thing to do. -

About Liver Resection

ABOUT LIVER RESECTION Surgical removal of part of the liver A guide for patients and relatives This booklet has been written to provide information about the operation called a liver resection. This is a major operation and involves removal of a part of the liver. Information about the benefits and risks will help you make an informed decision about the operation. It is important to remember that each person is different. This booklet cannot replace the professional advice and expertise of a doctor who is familiar with your condition. If you have questions that this booklet does not cover, please discuss them with your surgeon or cancer nurse specialist. page 2 What is the liver? The liver is a large organ which lies on the right side of the upper abdomen, under the rib cage. It has many functions related to body metabolism (chemical processes within the body) and is very important to health. One of its functions is to produce yellow-green fluid called bile. Bile flows down a tube called the bile duct to the intestine, where it mixes with food and helps digestion. The gall bladder is a small sac attached to the side of the bile duct. The gall bladder stores excess bile and pushes it down the bile duct in to the intestine, ready for when it is needed for digestion. The liver has right and left lobes (sections). An artery (hepatic artery) and a vein (portal vein) carry blood to the liver. Blood from the liver flows through the hepatic veins back to the heart. -

Tube Feeding Protocol: Supporting an Individual with a Feeding Tube

Tube Feeding Protocol: Supporting an Individual with a Feeding Tube Introduction Some people may be unable to take foods or fluids by mouth due to dysphagia. Others may require supplementation because they are unable to take sufficient foods or fluids by mouth, and formula delivered through a feeding tube may provide them with much needed additional nutrients. It is helpful if guidelines (A Tube Feeding Protocol) are in place prior to the need for this intervention. Below are some suggested guidelines for supporting an Individual with a feeding tube. Information to be documented by the physician The reason (medical diagnosis) requiring feeding tube insertion Type of feeding tube inserted Types of feeding tubes The Nasogastric Tube (NG tube): Passed into either nostril, down the esophagus and into the stomach. This is used for short term feedings. The Gastrostomy tube (G - tube or PEG): Surgically placed through the abdominal wall into the stomach. The tube will be located below the rib cage and to the left. The Jejunostomy tube (J - tube or PEJ): Surgically implanted in the upper portion of the jejunum (Part of the small intestine.) The tube will be located lower in the abdomen and more toward the center than the G – tube. Feedings through a J – tube must always be by pump. The Gastrostomy-Jejunostomy (GJ - tube): Surgically placed in the stomach, like the G – tube, but the tubing is longer, the end is in the jejunum, and there are two ports. Feeding technique Feeding techniques Bolus: A set amount of formula is given over a short period of time via syringe. -

Intestinal and Multiple Organ Transplantation 1679

1678 TRANSPLANT ATION euglycemia and survive longer than 200 islets in allogeneic and xenogeneic diabetic hosts. Transplant Proc 1993; 25:953-954. 67. Gotoh M, Maki T, Satomi S, et al: Immunological characteristics of purified islet grafts. Transplantation 1986; 42j387. 68. Klima G, Konigsrainer A, Schmid T, et al: Is the pancreas reo jected independently of the kidney after combined pancreatic renal transplantation? Transplant Proc 1988; 20:665. 69. Prowse 5J, Bellgrau D, Lafferty KJ: Islet allografts are destroyed by disease recurrence in the spontaneously diabetic BB rat. Di abetes 1986; 35:110. 70. Markmann JF, Posselt AM, Bassiri H, et al: Major-histocompat ibility-complex restricted and nonrestricted autoil1'\mune effec tor mechanisms in BB rats. Transplantation 1991; 52:662-667. 71. Navarro X, Kennedy WR, Loewenson RB, et al: Influence of pancreas transplantation on cardiorespiratory reflexes, nerve conduction, and mortality in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1990; 39:802. 72. Weber q, Silva FG, Hardy MA, et al: Effect of islet transplan tation on renal function and morphology of short- and long term diabetic rats. Transplant Proc 1979; 11:549. 73. Gotzche 0, Gunderson HJ, Osterby R: Irreversibility of glomer ular basement membrane accumulation despite reversibility of renal hypertrophy with islet transplantation in early diabetes. Diabetes 1981; 30:481. 74. Fung H, Alessini M, Abu-Elmagd K, et al: Adverse effects asso ciated with the use ofFK 506. Transplant Proc 1991; 23:3105. 75. Tzakis AG: Personal communication, 1991. I CHAPTER 185 Figure 185-1. Cluster allograft (shaded portion), including the liver, pancreas, and duodenal segment of small intestine. (From Starzl TE, Todo S. -

A Patient's Guide to Colostomy Care

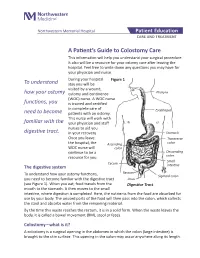

Northwestern Memorial Hospital Patient Education CARE AND TREATMENT A Patient’s Guide to Colostomy Care This information will help you understand your surgical procedure. It also will be a resource for your ostomy care after leaving the hospital. Feel free to write down any questions you may have for your physician and nurse. During your hospital Figure 1 To understand stay you will be visited by a wound, how your ostomy ostomy and continence Pharynx (WOC) nurse. A WOC nurse functions, you is trained and certified in complete care of Esophagus need to become patients with an ostomy. This nurse will work with familiar with the your physician and staff nurses to aid you digestive tract. in your recovery. Stomach Once you leave Transverse the hospital, the Ascending colon WOC nurse will colon continue to be a Descending resource for you. colon Small Cecum The digestive system intestine Rectum To understand how your ostomy functions, Sigmoid colon you need to become familiar with the digestive tract Anus (see Figure 1). When you eat, food travels from the Digestive Tract mouth to the stomach. It then moves to the small intestine, where digestion is completed. Here, the nutrients from the food are absorbed for use by your body. The unused parts of the food will then pass into the colon, which collects the stool and absorbs water from the remaining material. By the time this waste reaches the rectum, it is in a solid form. When the waste leaves the body, it is called a bowel movement (BM), stool or feces. -

Navigating Home Care: Parenteral Nutrition—Part Two

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #11 Series Editor: Carol Rees Parrish, M.S., R.D., CNSD Navigating Home Care: Parenteral Nutrition—Part Two by Gisela Barnadas Parenteral nutrition (PN) is often used for patients who are unable to absorb suffi- cient nutrition through the gastrointestinal tract. PN can be safely administered in the home setting with proper assessment and monitoring of the patient. An interdiscipli- nary team approach is used to identify and avoid potential complications, which may occur. This article provides the physician with specific guidelines for evaluating, ordering and monitoring PN therapy in the home patient. It also addresses financial and reimbursement considerations with emphasis on understanding the often con- fusing, Medicare guidelines. CASE 1 • What resources are available to help manage this JR is a 65-year-old female with vascular disease, patient in the home? hypertension, diabetes and history of a hysterectomy. • What resources are there available for the patient? She presents with severe abdominal pain, vomiting and • Will insurance pay for this? diarrhea. A small bowel series documents a bowel obstruction, most likely due to bowel ischemia. Find- Providing total parenteral nutrition in the home ings during surgical intervention included: twisted, (HPN) is by no means a new treatment option. The gangrenous small bowel with multiple adhesions first record of a patient receiving HPN was a 36-year- resulting in resection of her distal jejunum, ileum and old woman with extensive metastatic ovarian carci- right colon, leaving an intact duodenum, approximately noma in 1968.(1) While the exact number of people 100 cm of the jejunum and most of her left colon.