Learning and Memory Mathematical Models of Single Neurons Learning and Memory Learning and Memory Objective: Current Understanding of Learning and Memory Agenda: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Conditioning Without Awareness: an Electrophysiological Investigation

Classical conditioning without awareness: An electrophysiological investigation A Thesis Presented to The Division of Philosophy, Religion, Psychology, and Linguistics Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Jasmine Huang December 2016 Approved for the Division (Psychology) Timothy Hackenberg Michael Pitts Acknowledgements There is no way to express the amount of gratitude I feel towards every single person who has contributed to my growth as a student and as a human being, but I will try. My family, who has worked tirelessly to support me through life and years of school, I will never know how to repay that debt. My advisors, who have endlessly encouraged me and provided me with every opportunity I could have wished for. Tim who has believed in and supported me from my first year at Reed right up until the end. Enriqueta who was always willing to discuss experiments outside of class (even when I wasn’t in her class to begin with). Michael who inspired me every day with his unending enthusiasm and drive for research. The amazing psychology department staff who are always making sure that everything is running as smoothly as it can be. Joan, our silent hero who puts out the metaphorical fires every day. Greg, one the most lively presences in the animal colony, whose love for all of the critters is unparalleled. Chris, whose attention to detail and patience for dumb questions were invaluable to me during this process. Lavinia, whose realism and dark humor made for the best introduction into real labwork that I could have asked for. -

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Probing Echoic Memory with Different Voices

Memory & Cognition 1977, Vol. 5 (3),331-334 Probing echoic memory with different voices DAVID J. MADDEN and JARVIS BASTIAN University ofCalifornia, Davis, California 95616 Considerable evidence has indicated that some acoustical properties of spoken items are preserved in an "echoic" memory for approximately 2 sec. However, some of this evidence has also shown that changing the voice speaking the stimulus items has a disruptive effect on memory which persists longer than that of other acoustical variables. The present experiment examined the effect of voice changes on response bias as well as on accuracy in a recognition memory task. The task involved judging recognition probes as being present in or absent from sets of dichotically presented digits. Recognition of probes spoken in the same voice as that of the dichotic items was more accurate than recognition of different-voice probes at each of three retention intervals of up to 4 sec. Different-voice probes increased the likelihood of "absent" responses, but only up to a l.4-sec delay. These shifts in response bias may represent a property of echoic memory which should be investigated further. The concept of an "echoic" memory was first devel pairs of spoken consonants or vowels in a timed same/ oped by Neisser (1967), who proposed that a listener different recognition test. The items of a pair could be possesses a fairly literal but rapidly fading representation spoken in either the same voice or different voices, a of recent auditory events. Research motivated by this variable which was not relevant to the subjects' deci concept suggests that the exact time course of such sions. -

The Wandering Mind What the Brain Does When You Are Not Looking the University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2015, Pp

Michael C. Corballis The Wandering Mind What the Brain Does When You are Not Looking The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2015, pp. 184 It is commonplace to consider mind-wandering as a secondary, useless ac- tivity of our mind to which we guiltily abandon ourselves for laziness or dis- traction. The aim of the book is to show that, far from being the slaves of a blamable indolence, every time we are absent-minded or lost in thought, we are involved in an essential mental activity. Not only is mind-wandering a funda- mental component of our life (whether we want it or not, our mind meanders at night and for half the time during the day), but it also has a constructive and adaptive function that is crucial for facing the contingencies of a complex world. Without a wandering mind we would be stuck in the present, unable to invent stories and to escape the here and now through mental time travel. Mind-wandering takes us into unexplored regions of the unconscious mind that are inaccessible to the conscious will. Not only does this capacity allows us to build and consolidate the sense of our personality but it also helps to multiply our self into imagined possible selves and to expand the range of our experience. Creativity, too, lies in the randomness of mind-wandering, which makes possible unpredictable connections of ideas. The book therefore takes into account different forms of mind-wandering. Mental traveling depends on memory, which provides the material that feeds our imagination. Memory is so important to mind-wandering that some syn- dromes, such as amnesia and hyperthymesia, can impair the ability to mind- travel. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Henry Molaison of Facts and Events) and Acquisition of New Patient Who Became a Cause Célèbre in the Study of Memory Semantic Knowledge

OBITUARIES For the full versions of articles in this section see bmj.com declarative memory (conscious recollection Henry Molaison of facts and events) and acquisition of new Patient who became a cause célèbre in the study of memory semantic knowledge. Since his short term memory was intact, researchers concluded Henry Gustav Molaison, though known until Milner was published in the Journal of Neurology, that this did not depend on the removed his death only as HM to protect his privacy, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry in 1957 (20:11-21). It structures. Interestingly, HM was able to is considered to be “one of the most famous became one of the most highly cited articles in learn motor skills, implying a different type people in the history of psychology.” He the field, with 1744 citations to 2001. of memory mechanism. would undoubtedly be surprised to discover Psychosurgery was still popular in the HM did not know his age and was unable that his death has been commemorated by United States in the early 1950s. The paper to acquire new vocabulary. His retrograde extensive obituaries in leading non-medical gives the results of formal memory and amnesia extended back to the age of 16. publications, including the New York Times, Los intelligence testing of He appeared content Angeles Times, and Economist. Suzanne Corkin, nine patients who had at all times and rarely a psychologist at Massachusetts Institute of undergone bilateral complained of anything, Technology who worked with HM for 45 medial temporal lobe including pain, hunger, years and who is writing a book about her resection. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

Iconic Memory and Visible Persistence

Perception & Psychophysics 1980, Vol. 27 (3),183-228 Iconic memory and visible persistence MAX COLTHEART Birkbeck College, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, England There are three senses in which a visual stimulus may be said to persist psychologically for some time after its physical offset. First, neural activity in the visual system evoked by the stimulus may continue after stimulus offset ("neural persistence"). Second, the stimulus may continue to be visible for some time after its offset ("visible persistence"). Finally, information about visual properties of the stimulus may continue to be available to an observer for some time after stimulus offset ("informational persistence"). These three forms of visual persistence are widely assumed to reflect a single underlying process: a decaying visual trace that (1) con sists of afteractivity in the visual system, (2) is visible, and (3) is the source of visual informa tion in experiments on decaying visual memory. It is argued here that this assumption is incor rect. Studies of visible persistence are reviewed; seven different techniques that have been used for investigating visible persistence are identified, and it is pointed out that numerous studies using a variety of techniques have demonstrated two fundamental properties of visible per sistence: the inverse duration effect (the longer a stimulus lasts, the shorter is its persistence after stimulus offset) and the inverse intensity effect (the more intense the stimulus, the briefer its persistence). Only when stimuli are so intense as to produce afterimages do these two effects fail to occur. Work on neural persistences is briefly reviewed; such persistences exist at the photoreceptor level and at various stages in the visual pathways. -

Memory Stores Iconic Memory Decays Very Quickly, and This Explains Why

In the late 60's, serial position curves (Murdock, 1962) were used as evidence to support the MSM. Primacy efects were considered evidence of rehearsal and so long-term storage whereas recency efects were considered evidence of the short-term memory store. The serial position curve was shown to occur regardless of list length and recency was removed if there was a delay between rehearsal The initial approach was the information We will see why this is and recall. Evidence for the MSM processing approach which suggests that not the case sensory processes pass through several stores: throughout the Namely, the sensory memory store, the short- lectures. However, recency efects were demonstrated over term and then the long-term memory store. long time intervals by Baddeley et al. (1977). Recency is not reflect STM but a more general accessibility to more recent experiences. Memory Stores If short-term memory is post-categorical (as suggested by Neath and Merikle) then it requires information (category membership of letters) from long-term memory = There must be communication. Short-Term Memory Multi-Store Model (Atkinson & Shifrin, 1968) VS. Working Memory Short term is a simple store, whereas working memory is a 'mental workspace. STM is a part of working memory. Working memory allows manipulation to allow reasoning, learning and comprehension. It has a limited capacity, temporary store and has a speech like or phonological code (subvocal). Sensory Memory Baddeley (1966) Phonological Similarity: asked The Sufx Efect where a sufx (e.g spoken word Free Recall Studies where participants can participants to perform serial recall of 4 types of Visual Iconic Memory (Sperling, 1960) Purely at the end of the remembered list) drastically choose to recall from any part of the list. -

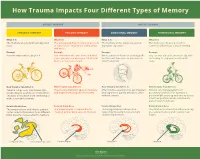

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology