Conservation Bulletin Issue 46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2040 D&A Statement DRAFT

2040/D/LC 14th April 2021 MORGAN CARN ARCHITECTS Blakers House 0004/A/V4 79 Stanford Avenue 20th December 2017 Brighton BN1 6FA T: 01273 55 77 77 PROJECT NO: 2040 F: 01273 55 22 27 [email protected] PROJECT: Conversion to Residential Use www.morgancarn.com LOCATION: Stanmer House, Stanmer Park Road, Brighton Cross Homes (Sussex) Ltd. 23 East StreetDESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT LEWES East Sussex BN7 2LJ 01.00 Introduction: For the attention of Robin Cross 01.01 This pre-application enquiry relates to the proposed conversion of the upper floors and parts of the ground floor of Stanmer House, a Grade 1 Listed building dating from 1722, to residential accommodation with parts of the ground floor left as a café to allow continued public access to the building. Dear Robin, 01.02 The proposals also include the demolition of the later single storey kitchen wing (which is not part of the original building) and the construction of a two-storey extension in the rear Re: With Morgan Carncourtyard | Architects to asprovide 19 pt Rajdhaniadditional Medium residential text & accommodation.1.25pt vertical red line in R=200 G=0 B=0 Address line, tel no, email etc as 8pt Rajdhani Regular. Main body of letter as 10pt Rajdhani Regular Please find enclosed for settlement our invoice no: 2860 which covers the provision of architectural services for the preparation of marketing CGI’s for the development. Should you have any queries, please do not hesitate to contact us. Yours faithfully, Lap Chan Director MORGAN CARN | ARCHITECTS Aerial View of Stanmer House Morgan Carn Limited trading as Morgan Carn Architects. -

Arquitectos Del Engaño

Arquitectos del Engaño Version original en Ingles CONTENIDO Explicaciones introductorias 4 1. Trance de consenso 6 Los mitos como base de poder 8 Gagarin nunca estuvo en el espacio 12 2. La oscura historia de los Caballeros Templarios 15 El origen de los Caballeros Templarios 17 La gran influencia de los Caballeros Templarios 18 Felipe IV contraataca 19 La maldición del gran maestre 22 El descubrimiento de Rennes-le-Chateau 23 3. El ascenso de la masonería 25 Comienza la infiltración 28 Las sociedades secretas se apoderan de los gremios de artesanos 31 El desarrollo del sistema masónico 35 Los grados mas altos 40 Otros ritos masónicos 42 Los símbolos 45 Magia masónica 54 Ideología masónica 62 4. El potente ámbito financiero 65 El interés como arma 67 Esclavitud económica 74 5. El poder global de la francmasonería 77 La francmasonería y la política 77 Los Illuminati 80 Estamos gobernados por los masones 85 Estados Unidos - La base executiva masónica 88 Harry Shippe Truman 95 El caso de Kissinger 99 Planos siniestros 101 La expansión de la masonería 104 P2 - La secta masónica mas infame 105 El Club 45 o "La logia roja de Viena" 114 La influencia masónica en Suecia 116 Los Carbonarios 117 La resistencia contra la francmasonería 119 El mundo masónico 127 6. La naturaleza roja i sangrante de la masonería 132 Los antecedentes históricos del Gran Oriente 133 La justicia de los masones 137 La corrupción masónica 141 La destrucción de Rusia 142 El soporte sanguinario de los comunistas 148 La aportación masónica en la Rusia Soviética 154 La lucha de Stalin contra la francmasonería 156 Los archivos secretos masónicos 157 La influencia oculta 158 7. -

Masonic Token

L*G*4 fa MASONIC TOKEN. WHEREBY ONE BROTHER MAY KNOW ANOTHER. VoLUME 5. PORTLAND, ME., MAY 15, 1913- No. 24. discharged. He reported that he had caused District Deputy Grand Masters. Published quarterly by Stephen Berry Co., $500 to be sent to the flood sufferers in Ohio. Districts. No. 37 Plum Street, Portland, Maine 1 Harry B. Holmes, Presque Isle. The address was received with applause. Twelve cts. per year in advance. 2 Wheeler C. Hawkes, Eastport. He presented the reports of the District 3 Joseph F. Leighton, Milbridge. Established March, 1867. - - 46th Year. Deputy Grand Masters and other papers, 4 Thomas C. Stanley, Brooklin. 5 Harry A. Fowles, La Grange. which were referred to appropriate com 6 Ralph W. Moore, Hampden. Advertisements $4.00 per inch, or $3.00 for half an incli for one year. mittees. 7 Elihu D. Chase, Unity. The Grand Treasurer and Grand Secre 8 Charles Kneeland, Stockton Springs. No advertisement received unless the advertiser, or some member of the firm, is a Freemason in tary made their annual reports. 9 Charles A. Wilson, Camden. good standing. 10 Wilbur F. Cate, Dresden. Reports of committees were made and ac 11 Charles R. Getchell. Hallowell. cepted. 12 Moses A. Gordon, Mt. Vernon. The Pear Tree. At 11:30 the Grand Lodge called off until 13 Ernest C. Butler, Skowhegan. 14 Edward L. White, Bowdoinham. 2 o’clock in the afternoon. When winter, like some evil dream, 15 John N. Foye, Canton. That cheerful morning puts to flight, 16 Davis G. Lovejoy, Bethel. Gives place to spring’s divine delight, Tuesday Afternoon., May 6th. -

GENERAL SYNOD February 2021 QUESTIONS & WRITTEN ANSWERS

GENERAL SYNOD February 2021 QUESTIONS & WRITTEN ANSWERS This paper lists written answers to questions submitted under Standing Orders 112-114 & 117. The Business Committee agreed on this occasion to exercise the provision under S.O. 117 to allow members the opportunity to give notice of questions for written answers between Groups of Sessions. The next Question Time also including a provision for supplementary questions will be at the next scheduled Group of Sessions (not, for the avoidance of doubt, at the webinar for Synod members on 27 February 2021). INDEX QUESTION 1 ARCHBISHOPS’ COUNCIL Safeguarding core groups & confidentiality Q1 QUESTIONS 2 – 23 HOUSE OF BISHOPS Vision & Strategy: learnings from local views Q2 Vision & Strategy and Setting God’s People Free Q3 Mission & effective use of church buildings Q4 Optimum level for administrative functions Q5 Climate change: reduction in emissions Q6 Abortion: view about pills by post Q7 Abortion: response to Government consultation Q8 Holy Communion: individual cups Q9 Holy Communion: legal opinion Q10 Holy Communion: distribution in both kinds Q11 LLF: conversion therapy Q12 Transgender and same sex marriage Q13 Selection & same sex marriage: policy Q14 Selection & views on same sex marriage Q15 The Culture of Clericalism Q16 Bullying of clergy by laity Q17 IDG Report: publication & follow up Q18 Safeguarding: scheme for support of survivors Q19 Withdrawn PTOs: guidelines Q20 Safeguarding: costs re Smyth case Q21 Safeguarding: publication of Makin Review Q22 Safeguarding: protocols -

BOARD of DEPUTIES of BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944.Pdf

THE LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (iFOUNDED IN 1760) GENERALLY KNOWN AS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1944 WOBURN HOUSE UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I 1945 .4-2. fd*׳American Jewish Comm LiBKARY FORM OF BEQUEST I bequeath to the LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (generally known as the Board of Deputies of British Jews) the sum of £ free of duty, to be applied to the general purposes of the said Board and the receipt of the Treasurer for the time being of the said Board shall be a sufficient discharge for the same. Contents List of Officers of the Board .. .. 2 List of Former Presidents .. .. .. 3 List of Congregations and Institutions represented on the Board .. .... .. 4 Committees .. .. .. .. .. ..10 Annual Report—Introduction .. .. 13 Administrative . .. .. 14 Executive Committee .. .. .. ..15 Aliens Committee .. .. .. .. 18 Education Committee . .. .. 20 Finance Committee . .. 21 Jewish Defence Committee . .. 21 Law, Parliamentary and General Purposes Committee . 24 Palestine Committee .. .. .. 28 Foreign Affairs Committee . .. .. ... 30 Accounts 42 C . 4 a פ) 3 ' P, . (OffuiTS 01 tt!t iBaarft President: PROFESSOR S. BRODETSKY Vice-Presidents : DR. ISRAEL FELDMAN PROFESSOR SAMSON WRIGHT Treasurer : M. GORDON LIVERMAN, J,P. Hon. Auditors : JOSEPH MELLER, O.B.E. THE RT. HON. LORD SWAYTHLING Solicitor : CHARLES H. L. EMANUEL, M.A. Auditors : MESSRS. JOHN DIAMOND & Co. Secretary : A. G. BROTMAN, B.SC. All communications should be addressed to THE SECRETARY at:— Woburn House, Upper Woburn Place, London, W.C.I Telephone : EUSton 3952-3 Telegraphic Address : Deputies, Kincross, London Cables : Deputies, London 2 Past $xmbmt% 0f tht Uoati 1760 BENJAMIN MENDES DA COSTA 1766 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1778 JOSEPH SALVADOR 1789 MOSES ISAAC LEVY 1800-1812 . -

The Cathedral Church of St Peter in Exeter

The Cathedral Church of St Peter in Exeter Financial statements For the year ended 31 December 2019 Exeter Cathedral Contents Page Annual report 1 – 13 Statement of the Responsibilities of the Chapter 14 Independent auditors’ report 15-16 Consolidated statement of financial activities 17 Consolidated balance sheet 18 Cathedral balance sheet 19 Consolidated cash flow statement 20 Notes 21 – 41 Exeter Cathedral Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 2019 REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Governing statute The Cathedral’s Constitution and Statutes were implemented on 24 November 2001 under the Cathedrals’ Measure 1999, and amended on 18 May 2007, 12 March 2014 and 14 January 2016, under the provisions of the Measure. The Chapter The administrative body is the Chapter. The members of the Chapter during the period 1 January 2019 to the date of approval of the annual report and financial statements were as follows: The Very Reverend Jonathan Greener Dean The Reverend Canon Dr Mike Williams Canon Treasurer The Reverend Canon Becky Totterdell Residentiary Canon (until October 2019) The Reverend Canon James Mustard Canon Precentor The Reverend Canon Dr Chris Palmer Canon Chancellor John Endacott FCA Chapter Canon The Venerable Dr Trevor Jones Chapter Canon Jenny Ellis CB Chapter Canon The Reverend Canon Cate Edmond Canon Steward (from October 2019) Address Cathedral Office 1 The Cloisters EXETER, EX1 1HS Staff with Management Responsibilities Administrator Catherine Escott Clerk of Works Christopher Sampson Director of Music Timothy -

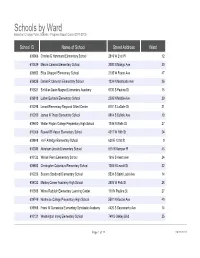

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

Newsletter 66 September 2017

THE CHAPELS SOCIETY Newsletter 66 September 2017 The modest Gothic exterior of Scholes Friends Meeting House [photograph copyright Roger Holden] I S S N 1357–3276 ADDRESS BOOK The Chapels Society: registered charity number 1014207 Website: http://www.chapelssociety.org.uk President: Tim Grass, 1 Thornhill Close, Ramsey, Isle of Man IM8 3LA; e-mail: [email protected]; phone: 01624 819619 (also enquiries about visits) Secretary: Moira Ackers, 1 Valley Road, Loughborough, Leics LE11 3PX; e-mail: [email protected] (for general correspondence and website) Treasurer: Jean West, 172 Plaw Hatch Close, Bishop’s Stortford CM23 5BJ Visits Secretary: position continues in abeyance Membership Secretary: Paul Gardner, 1 Sunderland Close, Borstal, Rochester ME1 3AS; e-mail: [email protected] Casework Officer: Michael Atkinson, 47 Kitchener Terrace, North Shields NE30 2HH; e-mail: [email protected] Editor: Chris Skidmore, 46 Princes Drive, Skipton BD23 1HL; e-mail: [email protected]; phone: 01756 790056 (correspondence re the Newsletter and other Society publications). Copy for the next (January 2018) Newsletter needs to reach the Editor by 30 November 2017, please. NOTICEBOARD CHAPELS SOCIETY EVENTS 30 September 2017 Conference (jointly with the Ecclesiological Society) on the architecture of less-well-studied denominations at the St Alban centre, London. 28 October 2017 Bristol visit (David Dawson & Stephen Duckworth) EDITORIAL This Newsletter will go out with details of our visit to Bristol and Kingswood, including to the refurbished New Room, in October. Our visits programme for next year is not yet finalised but we expect to have visits to Birmingham, probably concentrating on Bournville, in the spring and to West Sussex in the autumn. -

Wells Cathedral Library and Archives

GB 1100 Archives Wells Cathedral Library and Archives This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NR A 43650 The National Archives Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) WELLS CATHEDRAL LIBRARY READERS' HANDLIST to the ARCHIVES of WELLS CATHEDRAL comprising Archives of CHAPTER Archives of the VICARS CHORAL Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES Library PICTURES & RE ALIA 1 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) CONTENTS Page Abbreviations Archives of CHAPTER 1-46 Archives of the VICARS CHORAL 47-57 Archives of the WELLS ALMSHOUSES 58-64 Library PICTURES 65-72 Library RE ALIA 73-81 2 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ABBREVIATIONS etc. HM C Wells Historical Manuscripts Commission, Calendar ofManuscripts ofthe Dean and Chapter of Wells, vols i, ii (1907), (1914) LSC Linzee S.Colchester, Asst. Librarian and Archivist 1976-89 RSB R.S.Bate, who worked in Wells Cathedral Library 1935-40 SRO Somerset Record Office 3 Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) Stack 02(R) Library (East Cloister) ARCHIVES of CHAPTER Pages Catalogues & Indexes 3 Cartularies 4 Charters 5 Statutes &c. 6 Chapter Act Books 7 Chapter Minute Books 9 Chapter Clerk's Office 9 Chapter Administration 10 Appointments, resignations, stall lists etc. 12 Services 12 Liturgical procedure 13 Registers 14 Chapter and Vicars Choral 14 Fabric 14 Architect's Reports 16 Plans and drawings 16 Accounts: Communar, Fabric, Escheator 17 Account Books, Private 24 Accounts Department (Modern) 25 Estates: Surveys, Commonwealth Survey 26 Ledger Books, Record Books 26 Manorial Court records etc. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Sources for Church Property

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Sources for Church Property 1. Why did the Church Hold Property?............................................................................... 2 2. The Various Kinds of Church Property ........................................................................... 2 2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 2.2. Benefice Property ...................................................................................................... 2 2.3. Preferment Estates .................................................................................................... 3 2.4. Church Commissioners ............................................................................................. 4 2.5. Tithes......................................................................................................................... 5 2.6. Church Trusts ............................................................................................................ 5 2.7. Diocesan Boards of Finance ...................................................................................... 6 2.8. Commonwealth Ecclesiastical Estate Administration ................................................. 6 2.9. National Enquiries into Church Property .................................................................... 6 3. Research Value ............................................................................................................. 7 4. Other -

Time for Reflection

All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group TIME FOR REFLECTION A REPORT OF THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY HUMANIST GROUP ON RELIGION OR BELIEF IN THE UK PARLIAMENT The All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group acts to bring together non-religious MPs and peers to discuss matters of shared interests. More details of the group can be found at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmallparty/190508/humanist.htm. This report was written by Cordelia Tucker O’Sullivan with assistance from Richy Thompson and David Pollock, both of Humanists UK. Layout and design by Laura Reid. This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the Group. © All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, 2019-20. TIME FOR REFLECTION CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Recommendations 7 THE CHAPLAIN TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 8 BISHOPS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 10 Cost of the Lords Spiritual 12 Retired Lords Spiritual 12 Other religious leaders in the Lords 12 Influence of the bishops on the outcome of votes 13 Arguments made for retaining the Lords Spiritual 14 Arguments against retaining the Lords Spiritual 15 House of Lords reform proposals 15 PRAYERS IN PARLIAMENT 18 PARLIAMENT’S ROLE IN GOVERNING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 20 Parliamentary oversight of the Church Commissioners 21 ANNEX 1: FORMER LORDS SPIRITUAL IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 22 ANNEX 2: THE INFLUENCE OF LORDS SPIRITUAL ON THE OUTCOME OF VOTES IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 24 Votes decided by the Lords Spiritual 24 Votes decided by current and former bishops 28 3 All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group FOREWORD The UK is more diverse than ever before.