Design Guide for County Council Developments Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Leicestershire First published by English Heritage April 2012 Rebranded by Historic England December 2017 Introduction Leicestershire contains a wide range of distinctive building This is particularly true for the less common stone types. In stone lithologies and their areas of use show a close spatial some parts of the county showing considerable geological link to the underlying bedrock geology. variability, especially around Charnwood and in the north- west, a wide range of lithologies may be found in a single Charnwood Forest, located to the north-west of Leicester, building. Even the cobbles strewn across the land by the includes the county’s most dramatic scenery, with its rugged Pleistocene rivers and glaciers have occasionally been used tors, steep-sided valleys and scattered woodlands. The as wall facings and for paving, and frequently for infill and landscape is formed principally of ancient volcanic rocks, repair work. which include some of the oldest rocks found in England. To the west of Charnwood Forest, rocks of the Pennine Coal The county has few freestones, and has always relied on the Measures crop out around Ashby-de-la-Zouch, representing importation of such stone from adjacent counties (notably for the eastern edge of the Derbyshire-Leicestershire Coalfield. To use in the construction of its more prestigious buildings). Major the north-west of Charnwood lie the isolated outcrops of freestone quarries are found in neighbouring Derbyshire Breedon-on-the-Hill and Castle Donington, which are formed, (working Millstone Grit), Rutland and Lincolnshire (both respectively, of Carboniferous Limestone and Triassic working Lincolnshire Limestone), and in Northamptonshire (Bromsgrove) Sandstone. -

Hl'story and ANTIQUITIES of LEICESTERSHIRE

Hl'STORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF LEICESTERSHIRE. lands arid rents, with the appurtenances, are held of Green, Henry Bond, and Richard Sharpe. the king in capite, as parcel of the hbnou'r, castle, At the general election in 1722, 24 freeholders and manor of Belvoir \ polled from this parish; and 17 in 1775. In 1393, it appeared thftt John de Ros, of Ham- Nett expence of she poor in 1776, was £.22. 6s. Sa\ lake, deceased, was seifed of one park, called Belvoir Mediuhiot three years, 17^3—1785, £-34- !£*• bV; Park, in Redmile, and of one croft, called Leycrofr, The earliest register begins in 1653. and of a pasture, called Blakebergh Hill, in the fame In the first twenty years are 10 marriages, no parish, held of the king in tapite, by knight's service, baptisms, and 131 burials; and, in the twenty years as of the honour of Belvoir; that the said John de ending in l'j'dS-, are 47 marriages, 182 baptisms, and Ros gave to Richard de Schropjhdre, for his good ser- 116 burials. vice, fifteen messuages, one windmill, and five bovates In the register is this observation : and an half of land, with the appurtenances, in Red- " George TopSin and Jone Harrison had the baines mile, which are held of the king 111 capite •, and that of matrimony published three several Sabbaths in the William de Ros, knight* is the brother and next heir parish church of Redmile, and was married before of the before-mentioned John1. the alderman of Grantharti, upon the 13th of Fe* In 1394, Mary the wife of John de Ros, brother bruary, 1654." and heir of John de Ros, died seised of a thirty-third Richard Reave appointed register 1653^ part of one knight's fee in Redmile, which the heirs Richard Reave, the elder, late clerk of the parifli, of John Petit held K buried Jan. -

Leicestershire Record Office

LEICESTERSHIRE RECORD OFFICE The following records have been deposited during the period I January 1970- 31 December 1972: PARISH RECORDS I. Anstey (addl.): register of baptisms, marriages and buriailis, 1556-1571; register of baptisms and burials 1770-1812; registers of banns (2 vols.) 1865-1929; faculty 1892. 2. Arnesby: registers of baptisms, marriages (to 1753) and burials (2 vols.) 1602- 1812; register (stamped under 1783 Act) of baptisms, marriages (to 1787) and burials 1783-1794; registers of marriages, 1755-1837 (2 vols.); register of banns, 1824-1852; marriage licences (7) 1862-1943; faculties (5) 1829-1961; report on condition of church, 1903; report of the Archdeacon's inspection, 1928; curate's licence, 1860; Orders in CounciL re transfers of patronage, 1925, 1956; writs of _ sequestration, 1864-1957. Omrchwardens accounts (2 vols.) 1795-1934; church rate book c. 1848. Charities: Arnesby Loseby charity, receipts and payments books (2 vols.) 1817-19o6; correspondence with Charity Commissioners, 1954-56; Sunday School Charity: Order of Charity Commissioners, 1907, and correspondence, 1907- 16; school registers, 1954-56. SchoaL: deed of site, 1859, and Scheme of Charity Commissioners, 1865. 3. Ashby-de-la-Zouch: St. Helen's (addnl.): register of baptisms 1561-1719, marriages 1561-1729, and burials 1651-71, with Nonconformist births 1689~1727, and banns 1653-1657; register of baptisms 1719-82 and burials 1674-1759; register of baptisms (5 vols.) 1783-1881; registers of marriages (9 vols.) 1754-1864; registers of burials (4 vols.) 1760-1878. 4. Bagworth: registers of baptisms (2 vols.) 1813-1917; registers of marriages (5 vols. 1781-1934; register of burials 1813-95. -

Housing and Economic Development Needs

HEDNA Appendices Leicester and Leicestershire Authorities and the Leicester and Leicestershire Enterprise Partnership January 2017 Prepared by GL Hearn GL Hearn Limited 280 High Holborn London WC1V 7EE T +44 (0)20 7851 4900 glhearn.com HEDNA Appendices, January 2017 GL Hearn Page 2 of 134 F :\Documents\Temporary Files\HEDNA Final Documents\HEDNA Appendices (January 2017) (Final for Publication).docx HEDNA Appendices, January 2017 Contents Section Page 1 DEFINING THE HOUSING MARKET AREA 15 2 DEFINING THE FUNCTIONAL ECONOMIC MARKET AREA 40 3 MARKET SIGNALS OF COMPARABLE AUTHORITIES 49 4 FURTHER AFFORDABLE HOUSING NEEDS ANALYSIS 51 5 ANALYSIS OF STARTER HOME HOUSING NEEDS 71 6 LOCAL AUTHORITY LEVEL STARTER HOMES ANALYSIS 82 7 ADDITIONAL LOCAL LEVEL DEMOGRAPHIC FIGURES 106 8 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 127 9 RESIDENTIAL MARKET PERCEPTIONS FROM ESTATE AND LETTING AGENTS 132 GL Hearn Page 3 of 134 F :\Documents\Temporary Files\HEDNA Final Documents\HEDNA Appendices (January 2017) (Final for Publication).docx HEDNA Appendices, January 2017 List of Figures FIGURE 1: CURDS-DEFINED STRATEGIC HOUSING MARKET AREAS 18 FIGURE 2: CURDS-DEFINED LOCAL HOUSING MARKET AREAS 19 FIGURE 3: CURDS-DEFINED SILVER STANDARD HOUSING MARKET AREAS 20 FIGURE 4: DTZ-DEFINED SPATIAL BOUNDARIES IN EAST MIDLANDS 21 FIGURE 5: UNDERSTANDING HOUSING DEMAND DRIVERS 22 FIGURE 6: HOUSE PRICE PAID IN 2015 24 FIGURE 7: MEDIAN PRICE BY TYPE OF RESIDENCE 2015 25 FIGURE 8: GROSS WEIGHTED MIGRATION FLOWS 29 FIGURE 9: TRAVEL TO WORK AREAS (2011) 33 FIGURE 10: LOCATION OF WORKPLACE FOR -

The Old Windmill 20 the Green, Barkestone Le Vale Leicestershire Ng13 0Hh £250000

11 Market Place Bingham Nottingham NG13 8AR Tel: (01949) 87 86 85 [email protected] THE OLD WINDMILL 20 THE GREEN, BARKESTONE LE VALE LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0HH £250,000 THE OLD WINDMILL, 20 THE GREEN, BARKESTONE LE VALE, LEICESTERSHIRE NG13 0HH A substantial detached & characterful home 1345 sq ft of deceptively large accommodation Three / four bedrooms Delightful secluded & private garden to the rear Large double driveway A truly fascinating individual detached character property which offers a wealth of accommodation and features, situated at the heart of this pretty Vale of Belvoir village. As the name suggests, The Old Windmill is one of the original Windmills positioned within the Vale of Belvoir. Having fallen out of use at the beginning of the 20th Century, works began in the early 1980s to bring the Old Windmill back to its former glory with a complete overhaul when it was turned over to residential accommodation, with a wonderful homely atmosphere and likely to appeal to a wide audience. The property occupies a delightful plot with two main garden areas, the first to the rear is a sunny and private Courtyard (a perfect place to enjoy a glass of merlot or a G & T), with an archway leading into the second and more established garden area with mature trees and shrubs. This southerly facing Views across the rear garden towards Belvoir Caslte on the distance garden is perfect for those looking for a private and secure area away from the hustle and bustle of City life! HOW TO FIND THE OLD WINDMILL From the 'top room' there are views across the Vale of Belvoir towards Belvoir Castle up on the hill. -

North East Appendix B

NORTH EAST APPENDIX B NORTH EAST TRANSPORT SCHEMES DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2008/2009 ROAD COST PARISH/TOWN LOCATION DESCRIPTION STATUS NO BAND Buckminster Primary School 20mph Consultation Buckminster C School Zone Complete Substantially Burton on the Wolds Burton Primary School Traffic Calming C complete – developer funded Vehicle Activated Consultations A60 Cotes Loughborough Road C Sign (VAS) underway Croxton Kerrial C of E School 20mph Consultations Croxton Kerrial C Primary School Zone ongoing School 20mph East Goscote Broomfield Primary School C Preliminary design Zone School 20mph Gaddesby Gaddesby Primary School C Preliminary design Zone Consultations B6047 Great Dalby Great Dalby VAS/Gateway C ongoing Pedestrian Consultations A6 Hathern Derby Road B Crossing ongoing Hathern Loughborough Road Cycle Route C Preliminary design Cycle Route Consultations Loughborough Burleigh Way B Extension ongoing Cycle Route Loughborough Blackbrook Way C Complete Upgrade Complete Loughborough Badger Way Cycle Route C supported by Sustrans cont. – Complete Loughborough Lowden Way Cycle Route C supported by Sustrans cont. - Local Safety A6004 Loughborough Epinal Way/Ling Road Scheme – Route C Complete Treatment Local Safety A6004 Loughborough Epinal Way/Park Road Scheme – Route C Reserve Treatment Local Safety Bishop Meadow Loughborough Scheme – Route C Preliminary design Road/Belton Road West Treatment Fairmeadows Way/Laurel Rd (Outwoods Edge Loughborough Traffic Calming B Reserve Primary/Woodbrook Vale High School) 1 E:\moderngov\data\published\Intranet\C00000699\M00002244\AI00021398\AppendixBTSD0.doc ROAD COST PARISH/TOWN LOCATION DESCRIPTION STATUS NO BAND Robert Bakewell Primary School 20mph Consultations Loughborough C School Zone ongoing Woodbrook Vale High School 20mph Loughborough C Preliminary design School Zone Consultations Cycle Route ongoing – Loughborough Various – University Link C Upgrade supported by Sustrans cont. -

M Redmile Primary School.Pdf

M DEVELOPMENT CONTROL AND REGULATORY BOARD 24TH MARCH 2005 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNITY SERVICES APPLICATION UNDER REGULATION 3 OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING GENERAL REGULATIONS LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL – CONTINUED STANDING OF DOUBLE MOBILE CLASSROOM WITH TOILETS AND EXTENSION – REDMILE PRIMARY SCHOOL, BELVOIR ROAD, REDMILE (MELTON BOROUGH) 2005/0026/06 – 13th January 2005 Description of Proposal 1. Redmile Village is located in the north east of the county close to the border with Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. The school is located on the eastern edge of the village along Belvoir Road which runs between the A52 and A607. There are residential properties to the east and west screened by mature hedges and fence (about 1.5m high). On the East side there is also a narrow pasture field leading into a larger open field at the rear. There are extensive views to the south towards the escarpment on the edge of the Vale of Belvoir. 2. The Board granted permission for the replacement of a single mobile with a double mobile classroom in June 1999 (ref. 99/0306/06) for a period to expire on 31st July 2004. The mobile is located to the rear of the school, positioned on a grass area to the rear of the playground. Further to this, permission for a 1-bay extension to create a dining room was granted permission by the board in April 2001, for a period expiring on 31st July 2004. 3. The application is required to accommodate future pupil numbers at the school over the next 4 years. There are currently 63 pupils on roll at the school, which is set to reduce to 55 by the academic year 2008/9. -

Himp Maps Page2

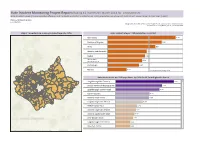

Hate Incident Monitoring Project Report: Rolling 12 months ll March 2014 for Leicestershire Hate Incident Levels (Police recorded offences and incidents and HIMP incidents) per 1000 populaon are shown at District and Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Choose Partnership Area Leicestershire Designed by Karen Earp, Research & Insight Team , Leicestershire County Council, Contact: [email protected] , 0116 305 7260 Map of Leicestershire showing incident levels by LSOA Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by district. -1 Charnwood 0.76 -1 Oadby and Wigston 0.61 -1 Blaby 0.53 0 Hinckley and Bosworth 0.44 0 Melton 0.42 North West 0 0.39 Leicestershire 0 Harborough 0.35 0 Rutland 0.21 Leicestershire Average 0.46 Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by LSOA for All from highest to lowest -9 Loughborough Bell Foundry 9.27 -7 Oadby The Parade & Leicester Ra.. 7.40 -7 Loughborough Toothill Road 7.00 -5 Coalville Centre 5.44 -5 Hinckley Town Centre 5.35 -4 Loughborough Centre South 4.34 -3 Melton Egerton East 3.46 -3 Hinckley Town Centre North 3.24 -3 Hinckley Castle South West 3.06 -3 Lile Bowden South 2.83 -2 Loughborough Centre West 2.39 -2 Measham Centre 2.39 -2 Loughborough Meadow Lane 2.37 About Tableau maps: www.tableausoftware.com/ mapdata Hate Incident Monitoring Project Report: Rolling 12 months ll March 2014 for Blaby Hate Incident Levels (Police recorded offences and incidents and HIMP incidents) per 1000 populaon are shown at District and Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Choose Partnership Area Blaby Designed by Karen Earp, Research & Insight Team , Leicestershire County Council, Contact: [email protected] , 0116 305 7260 Map of Blaby showing incident levels by LSOA Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by district. -

Academies in Leicestershire (As at June 2018)

Current and Proposed Academies in Leicestershire (as at June 2018) District School/College Type of School Blaby Blaby Stokes C.E. Primary School Primary Blaby Braunstone/Leicester Forest East Fossebrook Primary School Primary Blaby Braunstone Kingsway Primary School Primary Blaby Braunstone Millfield LEAD Academy Primary Blaby Braunstone Winstanley Community College Secondary Blaby Cosby Primary School Primary Blaby Countesthorpe Leysland and Countesthorpe Community College Secondary Blaby Croft C.E. Primary School Primary Blaby Enderby Brockington College Secondary Blaby Enderby Danemill Primary School Primary Blaby Glen Parva Glen Hills Primary School Academy Primary Blaby Glenfield Primary School Primary Blaby Huncote Community Primary School Academy Trust Primary Blaby Kirby Muxloe Primary School Primary Blaby Leicester Forest East Stafford Leys Community Primary School Primary Blaby Narborough Greystoke Primary School Primary Blaby Narborough Red Hill Field Primary School Primary Blaby Narborough The Pastures Primary School Primary Blaby Sapcote All Saints C.E. Primary School Primary Blaby Sharnford C.E. Primary School Primary Blaby Stoney Stanton Manorfield C.E. Primary Primary Blaby Whetstone St Peter's C.E. Primary School Primary Charnwood Anstey The Latimer Primary School Primary Charnwood Anstey The Martin High School Secondary 1 Current and Proposed Academies in Leicestershire (as at June 2018) District School/College Type of School Charnwood Anstey Wooden Hill Community Primary School Primary Charnwood Barkby The Pochin School -

Application M823 Melton

1 Definitive Map of Rights of Way for Leicestershire Register of Definitive Map Modification Order Applications Short Description: Footpath from Chapel Street to Rutland Square, Barkestone le Vale. Application No.: M823 Legal Services Ref. No.: HTWMT/1570 Application Status: Footpath Geographical Location Path No: G16a Route name (if known): Settlement: Barkestone le Vale Parish: Barkestone Plungar and Redmile District/Borough: Melton Nearest Town/City: Melton Mowbray Start Location: Chapel Street Start Grid Refs: Landranger: SK 781 347 Eastings,Northings: 478121,334763 End Location: Rutland Square End Grid Refs: Landranger: SK 781 348 Eastings,Northings: 478150,334813 Applicant’s Name, Address & Postcode: Barkestone Plungar and Redmile Parish Council, Clerk: Ms. L. Frances, Ringtree Cottages, Main Street, Woodthorpe by Belvoir, Grantham, NG32 1LT Date Received: 01 Oct 2008 Date Determined:* 15/05/2014 Application Stage(s): • th Development Control and Regulatory Board approval to make an Order 15 May 2014. For Further Information Case Officer: Mrs Ellen Senior Telephone: 0116 305 7085 Fax: 0116 305 7014 Email: [email protected] Contents List: Page: Application Form 2 Map accompanying the application 3 Additional Documents Inspector's Decision * Note the Determination Date is the occasion on which Leicestershire County Council formally decided whether or not to make an order in response to this application. 1 Form PT634 APPLICATION FOR DEFINITIVE MAP MODIFICATION ORDER WILDLIFE AND COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1981 DEFINITIVE MAP AND STATEMENT FOR THE COUNTY OF LEICESTERSHIRE Please complete this form and return it together with Form PT636, and any evidence you wish to submit, to: Environmental Management Group, Department of Community Services, Leicestershire County Council, County Hall, Glenfield. -

'Rrades. [Leioestebsbllie Farmers-Continued

780 'AR 'rRADES. [LEIOESTEBSBlliE FARMERs-continued. Lord George, Orton-on-the-Hill, Twy- Mason Alfred H.Burton-on-the-Wolds, Kirk William M. North manor, Crox- cross, Atherstone Six Hills, Leicester ton, Leicester (.ord J. T. Stapleford,Melton Mowbry Mason Mrs. Annie, Appleby Magna, Kirk Wm. Swift, Barkby, Leicester Lord S. Peashill 10. Mowsley, Rugby Atperstone Kirkman W. C., J.P. Manor house, (.ord T. Aston lane, Burbage, Hinckly Mason Edgar W. Barrowden, Stamfrd Barlestone, Nuneaton Lord Wm. Leicester Forest west, Mason Mrs.Grace, Barrowden,Stamfrd Knapp Stephen, Croxton, Leicester Desford. Leicester . Mason Mrs. Grace, Gaddesby,Leicestr Knifton William, Hemington, Derby Loseby William, Barkby, Leicester Mason Iven Sidney, Poultney, Nort.h . Knight Charles, Stonehouse farm, Lovett Binks, Nether Broughton, Kilworth, Rugby Packington, Ashby-de-Ia-Zouch Melton Mowbray Mason Joseph (exors. of), Walton- Knight John James, Outwood, Cole· Lovett Thos. G.Bottesford, Nottnghm on-the-Wolds, Loughborough orton, Ashby-de-Ia-Zouch Lovett Wm. Redmile, Nottingham Mason WaIter,Wigston Magna,Leicstr Knight Joseph, jun. Newbold, Worth- Lovett Wm. jun. Redmile, Nottinghm Massey Chas. Hy. Thornton, Leicestr" ing-ton, Ashby-de-la-Zouch Lovett Wm.E. Normanwn, Nottnghm Massey Mrs. W. Orton-on-the-Hill, Knight Mrs. M. S. Kilby, Leicester Lowe Ernest Albert,Goadby Marwood, Atherstone Knight Rd. Wm. Buckmnstr.Granthm Melton Mowbray Massey WaIter, Albert Village,Church Knight Robt. Belwn, Loughborough Lowe Mrs. Rd. Thornton, Leicester Gresley, Burton-on-Trem Knight Thomas, Glen Parva,Leicestr Lowe Thos. S. Countesthorpe, Leicstr Mather James, Thurcaston, Liecester Knight Walt-er, Braunstone, Lelce·ster Lowe William C. Glenfield, Leicpster Matthews David, Hall farm, Whit Knight William, Arlix farm, Packing- Lucas Joshua Frank, The Hall, East- well, Oakham. -

Superfast Leicestershire Journey

Stakeholder Event 6 – 8pm Tuesday 6 July 2016 Welcome & Introductions Cllr. Blake Pain Lead Member for Broadband 1) BT’s Fibre Rollout 2) Contract 1 Update 3) Contract 2 Deployment Plans 4) Better Broadband Scheme 5) Additional Funding 6) New Technology 7) Q&A session BT’s UK fibre broadband roll-out . £3bn to bring fibre to around two-thirds of UK . Today, more than 24 million homes and businesses passed . Around 8000 engineers working on the “Big Build” . A mixture of fibre to the cabinet (FTTC) and fibre to the premises technology (FTTP) . Fibre to the remote Node (FTTrN) – successfully trialled and now being deployed . FTTP “on demand” now available in some areas . More than 140 service providers currently trialling or selling fibre services using BT’s network . Extending fibre broadband availability even further through local community projects ‘ Community Fibre Partnership’ No other company in the world is investing as much in fibre without public sector support or a regulatory regime that allows for far greater returns The Superfast Leicestershire Journey 96% SFBB BT Commercial Contract 1 Contract 2 Going Further By March 15 By December 17 More than -£18.9m contract - £9.1m County The Final 4% 292,000 homes - 62,000 perms Contract Further Funding and business - £1.1m from - 11,000 prems connected districts - £2.26m of this contributing to is contribution around 5,000 form BT THP - New Leicester City phase £9.1m - £2.2m from contribution form LLEP LGF BT - £2.8m contribution from BT - 9,000 City prems How we do it… Pre-planning Preparing the Planning the Installation exchange network A full assessment Agree and plan Surveying Building the new of the existing when the new underground network from the network to provide equipment will be ducts and exchange to the accurate placed inside the planning where new street information for our exchange.