Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Public Sector Development Programme 2019-20 (Original)

GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2019-20 (ORIGINAL) Table of Contents S.No. Sector Page No. 1. Agriculture……………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Livestock………………………………………………………………………… 8 3. Forestry………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4. Fisheries…………………………………………………………………………. 13 5. Food……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 6. Population welfare………………………………………………………….. 16 7. Industries………………………………………………………………………... 18 8. Minerals………………………………………………………………………….. 21 9. Manpower………………………………………………………………………. 23 10. Sports……………………………………………………………………………… 25 11. Culture……………………………………………………………………………. 30 12. Tourism…………………………………………………………………………... 33 13. PP&H………………………………………………………………………………. 36 14. Communication………………………………………………………………. 46 15. Water……………………………………………………………………………… 86 16. Information Technology…………………………………………………... 105 17. Education. ………………………………………………………………………. 107 18. Health……………………………………………………………………………... 133 19. Public Health Engineering……………………………………………….. 144 20. Social Welfare…………………………………………………………………. 183 21. Environment…………………………………………………………………… 188 22. Local Government ………………………………………………………….. 189 23. Women Development……………………………………………………… 198 24. Urban Planning and Development……………………………………. 200 25. Power…………………………………………………………………………….. 206 26. Other Schemes………………………………………………………………… 212 27. List of Schemes to be reassessed for Socio-Economic Viability 2-32 PREFACE Agro-pastoral economy of Balochistan, periodically affected by spells of droughts, has shrunk livelihood opportunities. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

Motion Anwar Lal Dean, Bahramand Khan Tangi

SENATE SECRETARIAT ORDERS OF THE DAY for the meeting of the Senate to be held at 02:00 p.m. on Thursday, the 1'r August, 20 19. 1, Recitation from the Holy Quran. MOTION 2, SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEM, AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI, RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIIC SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERI, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZIA, MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. ASIF KIRMANI, DR. ASAD ASHRAF, SARDAR MUHAMMAD SHAFIQ TAREEN, SHERRY REHMAN, MIAN RAZA RABBANI, FAROOQ HAMID NAEK, ABDUL REHMAN MALIK DR. SIKANDAR MANDHRO, ISLAMUDDIN SHAIKH, RUBINA KHALID, GIANCHAND, KHANZADA KHAN, SASSUI PALIJO, MOULA BUX CHANDIO, MUSTAFA NAWAZ KHOKHA& SYED MUHAMMAD ALI SHAH ]AMOT, IMAMUDDIN SHOUQEEN, ENGR. RUKHSANA ZUBERI, QURATULAIN MARRI, KESHOO BAI, ANWAR LAL DEAN, BAHRAMAND KHAN TANGI AND MIR MUHAMMAD YOUSAF BADINI, tO MOVC,- "That leave be granted to move a resolution for the removal of Senator Muhammad Sadiq Sanjrani from the office of the Chairman, Senate of Pakistan." 2 RESOLUTION 3. SENATORS RAJA MUHAMMAD ZAFAR-UL-HAQ, LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, ATTA UR REHMAN, MOLVI FAIZ MUHAMMAD, ABIDA MUHAMMAD AZEEMI AGHA SHAHZAIB DURRANI' RANA MAHMOOD UL HASSAN, PERVAIZ RASHEED, MUSADIK MASOOD MALIK, SITARA AYAZ, MUHAMMAD JAVED ABBASI, MUHAMMAD USMAN KHAN KAKAR, MIR KABEER AHMED MUHAMMAD SHAHI, MOLANA ABDUL GHAFOOR HAIDERT, MUHAMMAD TAHIR BIZINJO, MUSHAHID ULLAH KHAN, SALEEM ZI^^ MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI KHAN JUNEJO, GHOUS MUHAMMAD KHAN NIAZI, RIANA MAQBOOL AHMAD, DR. -

The Politics of Federalism in Pakistan

The Politics of Federalism in Pakistan: An Analysis of the Major Issues of 18th and 20th Amendments Submitted by: Kamran Naseem Ph. D. Scholar Politics &I R Reg. No.22-SS/ Ph. D IR/ F 08 Supervisor: Dr. Amna Mahmood Department of Politics and IR Faculty of Social Sciences International Islamic University Islamabad 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………..……………………….…………………... 20-30 I.I State of the Problem I.II Scope of Thesis I.III Literature Review I.IV Significance of the Study I.V Objectives of the Study I.VI Research Questions I.VII Research Methodology I.VIII Organization of the Study Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework ………..……………………………...……… 31-56 1.1 Unitary System 1.2 Some Similarities in Characteristics of the Federal States 1.2.1 Distribution of Powers 1.2.2 Independence of the Judiciary 1.2.3 Two Sets of Government 1.2.4 A Written Constitution 1.3 Federalism is Debatable 1. 4 Ten Yardsticks of Federalism 1.4.1 One: Comprehensive Control over Foreign Policy 1.4.2 Two: Exemption against Separation 1.4.3 Three: Autonomous Domain of the Centre 1.4.4 Four: The Federal Constitution and Amendments 1.4.5 Five: Indestructible Autonomy and Character 1.4.6 Six: Meaningful and Remaining Powers 1.4.7 Seven: Representation on parity basis of unequal Units and Bicameral Legislature at Central Level 1.4.8 Eight: Two Sets of Courts 1.4.9 Nine: The Supreme Court 2 1.4.10 Ten: Classifiable Distribution of Power 1.4.11 Debatable Results of Testing the Yardsticks of Federalism 1.5 Institutional theory 1.5.1 Old Institutionalism 1.5.2 The New Institutionalism -

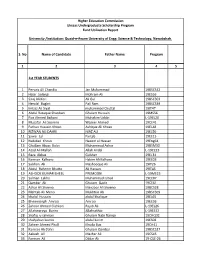

S. No Name of Candidate Father Name Program 1 2 3 4 5 1St YEAR STUDENTS 1 Pervaiz Ali Chandio Jan Muhammad 19BSCS42 2 Halar

Higher Education Commission Ehsaas Undergraduate Scholarship Program Fund Utilization Report University /Institution: Quaid-e-Awam University of Engg: Science & Technology, Nawabshah. S. No Name of Candidate Father Name Program 1 2 3 4 5 1st YEAR STUDENTS 1 Pervaiz Ali Chandio Jan Muhammad 19BSCS42 2 Halar Solangi Mohram Ali 19ES16 3 Siraj Ali Kori Ali Gul 19BSCS03 4 Heralal Baghri Pali Ram 19BSCS39 5 Imtiaz Ali Siyal muhammad Chuttal 19IT47 6 Abdul Razaque Shanbani Ghulam Hussain 19MS56 7 Fiaz Ahmed Bajkani Muhakim Uddin L-19EL20 8 Muzafar Ali Soomro Wazeer Ahmed 19CE41 9 Farhan Hussain Khoso Ashique Ali Khoso 19EL48 10 RIZWAN ALI DAHRI NIAZ ALI 19EL50 11 Sawai Lal Partab 19EE15 12 Nabidad Khoso Naeem ul Hassan 19Eng64 13 Ghullam Abass Kaloi Muhammad Achar 19BSM30 14 Azad Ali Mallah Allah Andal L-19CE23 15 Raza Abbas Gulsher 19EL34 16 Kamran Kalhoro Hakim Ali Kalhoro 19EE03 17 Subhan Ali Mashooque Ali 19IT26 18 Abdul Raheem Bhutto Ali Hassan 19IT45 19 ASHOOK KUMAR BHEEL PREMOON L-19ME23 20 Salman Lakho Muhammad Ismail 19CE07 21 Qambar Ali Ghulam Qadir 19CE61 22 Azhar Ali Sheeno Manzoor Ali Sheeno 19BCS28 23 Mehtab Ali Meno Mukhtiar Ali 19BSCS09 24 khalid Hussain abdul khalique 19EL65 25 Bheemsingh Amroo Amroo 19EE36 26 Zahoor Ahmed Gishkori Rajab Ali L-19EL26 27 Allahwarayo Buriro Allahrakhio L-19ES32 28 Shafiq u rahman Ghulam Nabi Narejo 19CHQ32 29 shahjahan keerio abdul karim 19ES02 30 Zaheer Ahmed Phull Khuda Bux 19CH41 31 Kamran Ali Dahri Ghulam Qambar 19BSCS27 32 Aakash Ali Mazhar Ali 19CS45 33 Farman Ali Dildar Ali 19-CSE-26 34 -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Historical Sketch of Peasant Activism: Tracing Emancipatory Political Strategies of Peasant Activists of Sindh

International Journal Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 3, Issue 5, Sep 2014, 23-42 © IASET HISTORICAL SKETCH OF PEASANT ACTIVISM: TRACING EMANCIPATORY POLITICAL STRATEGIES OF PEASANT ACTIVISTS OF SINDH GHULAM HUSSAIN 1 & ANWAAR MOHYUDDIN 2 1MPhil Scholar, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 2 Lecturer, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT Peasant activism in Sindh is very diverse and has its own typical history. Temporally, it has been focused on contextual issues that demand more than just land reforms. Peasant activists have, over the years, pursued roughly articulated, expedient and highly diverse agendas that are enacted by the mix of civil society activists, NGOs and ethnic peasant activists. In this article, which is the result of ethnographic study and the analysis of secondary ethnographic and historical data, effort has been made to trace the formation of peasantivist agendas and strategies in Sindh, particularly tracing it from the peasant struggle of Shah Inayat in 17 th century. The introduction of exploitative Batai system during British rule, the consequent institutionalization of sharecropping, establishment of Hari Committee in 1930s, the launching of Batai Tehreek and Elati Tehreek have been traced in relation to shifting peasantivist agendas. Failure of peasant activists to bring about substantive land reforms and the recent process of NGO-ising of peasant activism, have been analyzed vis-à-vis historical past. KEYWORDS: Peasant Activism, Peasant Movements, N.G.Os INTRODUCTION In this study the genesis of exploitation in peasant communities of Sindh has been elaborated, and the historical analysis of some of the important peasant struggles, rebels, and movements have been done to understand where peasants and peasant activist in Sindh stands now. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

The Impact of Presidential Appointment of Judges: Montesquieu Or the Federalists?

The impact of Presidential appointment of judges: Montesquieu or the Federalists? BY SULTAN MEHMOOD∗ March 2021 A central question in development economics is whether there are adequate checks and balances on the executive. This paper provides causal evidence on how increasing constraints on the executive, through removal of Presidential discretion in judicial appointments, promotes rule of law. The age structure of judges at the time of the reform and the mandatory retirement age law provide us with an exogenous source of variation in the removal of Presidential discretion in judicial appointments. According to our estimates, Presidential appointment of judges results in additional land expropriations by the government worth 0.14 percent of GDP every year. (JEL D02, O17, K11, K40). Keywords: President, judges, property rights, court subversion, expropriation risk. ∗ Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) and New Economic School (E-mail: [email protected]). First Draft: August 2016. This Version: March 2021. A previous version of this paper was entitled, Judicial Independence and Economic Development: Evidence from Pakistan. I would like to thank Eric Brousseau, Daron Acemoglu, Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee, Andrei Shleifer, Daniel Chen, Ekaterina Zhuravskaya, Ruben Enikolopov, James Robinson, Henrik Sigstad, Ruixue Jia, Saad Gulzar, Yasir Khan, Jean-Philippe Platteau, Thierry Verdier, Sergei Guriev, William Howell, Georg Vanberg, Anandi Mani, Adam Szeidl, Monika Nalepa, Nico Voigtlaender, Christian Dippel, Paola Giuliano, Thomas -

NEWS and EVENTS News and Reports Amnesty Film Festival

Member Center | Student Center NEWS AND EVENTS Home > News and Events > News and Reports News and Reports PAKISTAN Amnesty Film INSUFFICIENT PROTECTION OF WOMEN Festival government of Pakistan vigorously condemns the p Annual General 1. INTRODUCTION Meeting Regional For years, women in Pakistan have been severely disadvantaged and discriminated against. Conferences They have been denied the enjoyment of a whole range of rights - economic, social, civil and political rights and often deprivation in one of these areas has entailed discrimination in Leadership Summit another. Women who have been denied social rights including the right to education are also Local Events often denied the right to decide in matters relating to their marriage and divorce, are more easily abused in the family and community and are more likely to be deprived of the right to Nationwide Events legal redress. Often abuses are compounded; poor girls and women are trafficked and subject to forced marriage, forced prostitution or exploitative work situations such as bonded labour. In all of these situations they are likely to be mentally, physically and sexually abused, again without having the wherewithal to obtain justice.(1) Since publishing its 1999 report, Pakistan: Violence against women in the name of honour(2), Amnesty International has found that while few positive changes have taken place in the area of women's rights, the state in Pakistan still by and large fails to provide adequate protection for women against abuses in the custody of the state and in the family and the community. In fact, the number of victims of violence appears to rise. -

Pakistan Security Challenges.Pdf

Balochistan January 2011 REPORTS I. Causes of Instability in Pakistan 14 II. Balochistan – Pakistan's Festering Wound! 83 III. Karachi – Seething Under Violence and Terror 135 CRSS - 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Causes of Instability in Pakistan SECTION I Structural Causes of Instability 14 1. Objectives Resolution 14 1.1 The Question of Minorities 16 2. Imbalanced Civil-Military Relations 18 3. Absence of Good Governance 21 3.1 Institutional Deficiencies 22 3.2 Corruption 25 3.3 Deficient Rule of Law 27 3.4 Incapacities of Public Sector Personnel 28 3.5 Lack of Political Will within Ruling Elite 28 3.6 Flawed Taxation System 29 3.7 Rising Inflation 30 4. Inter-Provincial Disharmony 31 4.1 Distribution of Resources among Provinces 31 4.2 Provincial Autonomy under 18th Amendment 32 4.3 Nationalist Movements 33 4.3 (a) Balochistan Movement 33 4.3 (b) Seraiki Movement 35 4.3 (c) Hazara Movement 36 4.4 Inter-Provincial Water Distribution Row 37 4.5 Provinces' Representation in the Army 38 4.6 Federal Legislative List-Part II (of the Constitution of Pakistan) 40 5. Socio-Economic Problems 40 5.1 Poverty 40 5.1 (a) Growing Trend of Militancy 42 5.1 (b) Increase in Suicide Incidents 42 5.2 Illiteracy 43 5.3 Unemployment 44 CRSS - 2010 6. Army's Predominance of Foreign Policy 45 6.1 Army's Role in Kashmir Policy 46 6.2 Army's Role in Afghan Policy 47 6.3 Army's Role in U.S. Policy 48 7. Geography 49 7.1 Pakistan's Border with India 50 7.2 Pakistan's Border with Afghanistan 51 7.3 Pakistan's Border with Iran 51 7.4 America's Interests in the Region 53 8.