Nietzsche's Transfiguration of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Nietzsche: Looking Right, Reading Left

Educational Philosophy and Theory ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rept20 Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left Babette Babich To cite this article: Babette Babich (2020): Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left, Educational Philosophy and Theory, DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 Published online: 16 Nov 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 394 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rept20 EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY AND THEORY https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 EDITORIAL Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left The far right appropriates a Nietzsche invented out of its own fantasies, likewise the left in its critique of these appropriations, battles a projection cobbled in response to that of the far right. If centrist visions likewise exist, many, for want of likely suspects, relegate these to the left. Indeed, in their lead contribution to their collection on The Far Right, Education, and Violence, Michael Peters and Tina Besley point out that the cottage industry of Nietzsche mis- appropriations, especially those kipped to the right, has been booming for more than a cen- tury (Peters & Besley, 2020, p. 5; cf. Alloa, 2017; Illing, 2018; Kellner, 2019). Beyond the pell-mell of misreadings and prototypically ‘Nazi’ bowdlerization under Hitler, Peters and Besley rightly point out that what they name the “‘pedagogical problem’” (Peters & Besley, 2020, p. 10) can be located at the heart of such a political free for all, on the right as on the left. -

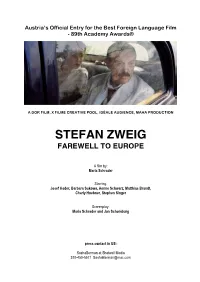

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

The 'New' Heidegger

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections 1-2015 The ‘New’ Heidegger Babette Babich [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, Radio Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, "The ‘New’ Heidegger" (2015). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 65. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 10 The ‘New’ Heidegger Babette Babich 10.1 Calculating Heidegger: From the Old to the New The ‘new’ Heidegger corresponds less to what would or could be the Heidegger of the moment on some imagined ‘cutting edge’ than it corresponds to what some wish they had in Heidegger and above all in philosophical discussions of Heidegger’s thought. We have moved, we suppose, beyond grappling with the Heidegger of Being and Time . And we also tend to suppose a fairly regular recurrence of scandal—the current instantiation infl amed by the recent publication of Heidegger’s private, philosophical, Tagebücher, invokes what the editor of these recently published ‘black notebooks’ attempts to distinguish as Heidegger’s ‘historial antisemitism’ — ‘historial’ here serving to identify Heidegger’s references to World Jewry in one of the volumes. -

Wir Brauchen Einen Ganz Anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied Von Europa 3

Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Wir brauchen einen ganz anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied von Europa 3. April 2014 bis 12. Jänner 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Als der österreichische Schriftsteller Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) 1934 nach England und in der Folge nach Brasilien emigrierte, verließ ein überaus erfolgreicher Autor Europa. Dennoch sind es zwei Werke, die Zweig erst im Exil verfasst hat, die heute sein Bild bestimmen. Im Blick auf Die Welt von Gestern und die Schachnovelle entdeckt das Theatermuseum Zweigs Leben und Werk auf neue Weise. Es ist die Perspektive der Vertreibung, die die Ausstellung charakterisiert. Angelpunkt der Gestaltung ist das „Metropol“, das als mondänes Hotel das Fin de siècle ebenso repräsentiert, wie es als Gestapo-Hauptquartier zum Schreckensort schlechthin wurde. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Trägt die Sprache schon Gesang in sich... Richard Strauss und die Oper 12. Juni 2014 bis 9. Februar 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Richard Strauss zählt zu den wichtigsten Komponisten der beginnenden Moderne und wurde als Opernkomponist in aller Welt geschätzt. Strauss unterhielt zahlreiche Verbindungen nach Wien, wo er zwischen 1919 und 1924 als Direktor der Wiener Staatsoper große Triumphe, aber auch zahlreiche Niederlagen erlebte. Anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages präsentiert das Theatermuseum seine umfangreichen Strauss-Bestände, unter ihnen die Korrespondenz mit Hugo von Hofmannsthal sowie den großen Schatz an Bühnenbild- und Kostümentwürfen von Alfred Roller. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Theatermuseum. -

A Hero's Work of Peace: Richard Strauss's FRIEDENSTAG

A HERO’S WORK OF PEACE: RICHARD STRAUSS’S FRIEDENSTAG BY RYAN MICHAEL PRENDERGAST THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Katherine R. Syer ABSTRACT Richard Strauss’s one-act opera Friedenstag (Day of Peace) has received staunch criticism regarding its overt militaristic content and compositional merits. The opera is one of several works that Strauss composed between 1933 and 1945, when the National Socialists were in power in Germany. Owing to Strauss’s formal involvement with the Third Reich, his artistic and political activities during this period have invited much scrutiny. The context of the opera’s premiere in 1938, just as Germany’s aggressive stance in Europe intensified, has encouraged a range of assessments regarding its preoccupation with war and peace. The opera’s defenders read its dramatic and musical components via lenses of pacifism and resistance to Nazi ideology. Others simply dismiss the opera as platitudinous. Eschewing a strict political stance as an interpretive guide, this thesis instead explores the means by which Strauss pursued more ambiguous and multidimensional levels of meaning in the opera. Specifically, I highlight the ways he infused the dramaturgical and musical landscapes of Friedenstag with burlesque elements. These malleable instances of irony open the opera up to a variety of fresh and fascinating interpretations, illustrating how Friedenstag remains a lynchpin for judiciously appraising Strauss’s artistic and political legacy. -

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort. Von Clara Körben . 3 I. Aus österreichischem Geiste. Aphorismen. Von Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach 9 Der Schleier der Beatrice (Schlußverse). Von Arthur Schnitzler .... 10 Die verwandelte Welt. Von Hans Müller 11 Das Landgut der Fiametta. Von Raoul Auernheimer 13 Lemberg. Von Thaddäus Rittner 22 Die Flöte. Von Franz Karl Ginzkey 23 Die Helfenden. Von Lola Lorme 24 Bischof Dr. Rudolf Hittmair und Enrita von Handel-Mazzetti. Mitgeteilt von Enrika von Handel-Mazzetti (aus der Hittmair-Biographie von Pesendorfer) . 25 Ostermorgen im Felde. Von Mathilde Gräfin Stubenberg 30 Deutsches Wiegenlied. Von Alfons Petzold 30 Dem Hiasl fei Feldpost (steirisch). Von Hermann Kienzl 31 Der Sommer. Von Peter Attenberg 32 Der Frosch. Von Peter Altenberg 32 Deutsche Lehre. Von Hans Fraungruber 33 Die Leute vom blauen Guguckshaus. Von Emil Ertl (aus der Roman- Trilogie „Ein Volk an der Arbeit") 33 Adria-Idyllen. Von Irma von Höfer 45 England und die Kulturphilosophie Bacon-Shakespeares in ihren Beziehungen zum gegenwärtigen Weltkrieg. Von Hofrat Alfred von Weber-Ebenhof 50 St. Michael. Von Gabriele Fürstin Wrede 64 Echt österreichisch. Von Marianne Schrutka von Rechtenstamm ... 65 Zwei Tannen. Don Else Rubricius 66 II. An Österreichs Schwert. Zum 18. August 1915. Von Peter Rosegger 69 Das große Händefalten. Von Anton Wildgans 69 Mein Österreich. Von Richard Schaukal 71 Die Kriegssage vom Untersberg. Von GiselavonBerger 72 Die Glocken kommen. Von Angelika von Hörmann 76 Schwertbrüder. Von Karl Rogner 77 Österreichisches Reiterlied. Von Hugo Iuckermannf . 78 Przemysl. Von Maria Eugenia teile Grazie 79 Weihnachten in Przemysl. Von Herma von Skoda 80 Aus» Osterreich, aus. Von HermavonSkoda 81 5 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch N/" http://d-nb.info/362276870 31 "HEI1 Seite Mein Bub. -

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960 David Wile Advisor: Dr. Alan Levine, School of Public Affairs University Honors Spring 2012 Wile 1 Abstract Between 1870 and 1960, the United States of America and Austria experienced two opposite political paths. The United States emerged from the wreckage of the Civil War as a more centralized republic and at the turn of the century became an imperial power, a status that the First and Second World Wars only solidified. Meanwhile, Austria ended the nineteenth century as one of Europe’s largest empires, yet after World War I, all that remained of the intellectual and cultural center of the Habsburg Empire was a tiny remnant cut off from its breadbasket in Hungary, its industrial center in Bohemia, and its seaports in the Balkans. Against the backdrop of a dying empire observing a nascent one, this project examines the discourse through which prominent members of the Austrian, and especially Viennese, intellectual elite imagined the United States of America, and attempts to determine which patterns emerged in that discourse. The Austrian thinkers and writers who are the major focus of this work are: the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the Zionist Theodor Herzl, the feuilletonist and satirist Karl Kraus, two of the most prominent members of the Austrian School of economics, Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, and an economist of the Historical School, Joseph Schumpeter. To a lesser extent, the work refers to writers Stefan Zweig, Albert Kubin, and Arthur Schnitzler, philosophers Otto Weininger and Franz Brentano, and two more Austrian School economists, Carl Menger and Friedrich von Wieser. -

On Nietzsche's Schopenhauer, Illich's

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections Spring 2014 “Who do you think you are?” On Nietzsche’s Schopenhauer, Illich’s Hugh of St. Victor, and Kleist’s Kant Babette Babich Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, "“Who do you think you are?” On Nietzsche’s Schopenhauer, Illich’s Hugh of St. Victor, and Kleist’s Kant" (2014). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 68. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J P S E Journal for the Philosophical Study of Education Vol. 2 (2014) Editors: Allan Johnston, DePaul University and Columbia College Chicago Guillemette Johnston, DePaul University Outside Readers: Charles V. Blatz, University of Toledo (emeritis) Tom Falk, University of Dayton Tom Friedrich, SUNY Plattsburgh Charles Howell, Youngstown State University Emery Hyslop-Margison, Florida Atlantic University Cheu-jey Lee, Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne Alexander Makedon, Arellano University David Mosley, Bellarmine University Linda O’Neill, Northern Illinois University Sam Rocha, University of North Dakota Zachary Rohrbach, Independent Scholar Elias Schwieler, Stockholm University The Society for the Philosophical Study of Education JPSE: Journal for the Philosophical Study of Education II (2014) “Who do you think you are?” On Nietzsche’s Schopenhauer, Illich’s Hugh of St. -

Cultural Amnesia

Marcel Reich-Ranicki arcel Reich-Ranicki (b. 1920), by far the most famous critic in Germany between World War II Mand the millennium, continues, into the twenty-first century, to exercise, over the German literary scene, a dominance which some writers prefer to regard as a reign of terror. Actually there can be no real argument about the fairness of his judgements – a fact which, of course, makes his disapproval feel even worse for those found wanting. He writes so well that his opinions are quoted verbatim. Victims of a put-down are thus faced with the prospect of becoming a national joke. Most of those writers whose later books were savaged by him had their early books praised by him: those are the writers who become most resentful of all against him. Well equipped to look after himself, he is hard to lay a glove on. Watching magisterial figures such as Günter Grass vainly trying to get their own back on Reich-Ranicki is one of the entertainments of modern Germany. Even those wounded by him would have to admit, under scopolamine, that he can be very funny when on the attack. Hence their intense enjoyment of the moment when history caught him out. Deported from Berlin to the Warsaw ghetto in 1938, Reich-Ranicki survived the Holocaust but stayed on in Communist Poland after the war, and first pursued literary criticism under East German auspices. When he finally defected to the West he forgot to tell anyone that he had been a registered informer under the regime he left behind. -

"Thus Spoke Zarathustra" Or Nietzsche and Hermeneutics in Gadamer, Lyotard, and Vattimo Babette Babich Fordham University, [email protected]

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections Summer 2010 "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" or Nietzsche and Hermeneutics in Gadamer, Lyotard, and Vattimo Babette Babich Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, ""Thus Spoke Zarathustra" or Nietzsche and Hermeneutics in Gadamer, Lyotard, and Vattimo" (2010). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 30. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ( "Thus Spoke Zarathustra, II or Nietzsche and Hermeneutics in Gadamer, Lyotard, and Vattimo Babette Babich Your true educators and formative teachers reveal to you what the real raw material of your being is, sOlnething quite inedu cable, yet in any case accessible only with difficulty, bound, para lyzed: your educators can be only your liberators. -Friedrich Nietzsche, Schopenhauer as Educator Nietzsche and Hermeneutics I aln not -

The Ister» Documentary and Heidegger’S Lecture Course: on Politics, Geographies, and Rivers

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections 2011 The sI ter: Between the Documentary and Heidegger’s Lecture Course Politics, Geographies, and Rivers Babette Babich Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Human Geography Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, "The sI ter: Between the Documentary and Heidegger’s Lecture Course Politics, Geographies, and Rivers" (2011). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 38. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/38 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Babette Babich «THE ISTER» DOCUMENTARY AND HEIDEGGER’S LECTURE COURSE: ON POLITICS, GEOGRAPHIES, AND RIVERS Documentary Passages: On Journeying and Wandering The Ister, the 2004 documentary by the Australian scholars and videographers, David Barison, a political theorist, and Daniel Ross, a philosopher, appeals to Martin Heidegger’s 1942 lecture course, Hölderlins Hymne «Der Ister»1 and the video takes