OREGON LAW REVIEW [Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 1, 2016 TO: the Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: No

September 1, 2016 TO: The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: Notice of Board Meeting The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon will hold a meeting on the date and at the location set forth below. Topics at the meeting will include: a recommendation regarding Dunn Hall; seconded motions and referrals from September 8, 2016, committee meetings; presidential report; presidential assessment report; AY16‐17 tuition and fee setting‐process; “Clusters of Excellence” in focus; federal funding; and an update on UO Portland. The meeting will occur as follows: Thursday, September 8, 2016 – 2:00 pm Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom Friday, September 9, 2016 – 9:30 am Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom The meeting will be webcast, with a link available at www.trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings. The Ford Alumni Center is located at 1720 East 13th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon. If special accommodations are required, please contact Amanda Hatch at (541) 346‐3013 at least 72 hours in advance. BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6227 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403‐1266 T (541) 346‐3166 trustees.uoregon.edu An equal‐opportunity, affirmative‐action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon Public Meeting September 8-9, 2016 Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8 – 2:00 pm – Convene Public Meeting - Call to order, roll call, verification of quorum - Approval of June 2016 minutes (Action) - Public comment Those wishing to provide comment must sign up advance and review the public comment guidelines either online (http://trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings) or at the check-in table at the meeting. -

2MFM Newsletter 12 2020

DECEMBER QUERIES DECEMBER 2020 How do our social and economic choices help or harm our vulnerable neighbors? The Multnomah Friends Meeting Do we consider whether the seeds of war and the displacement of peoples Monthly have nourishment in our lifestyles and possessions? Newsletter How does the Spirit guide us in our relationship to money? 4312 SE STARK STREET, PORTLAND, OREGON 97215 (503) 232-2822 WWW.MULTNOMAHFRIENDS.ORG FRIENDLY FACES: Sisters Alegría and Confianza of Las Amigas Del Señor Monastery “People will lie to their doctor about three things: smoking, drinking, and sex,” said Sister Alegría of the two-person Las Amigas del Señor Methodist-Quaker Monastery in Limón, Colón, Honduras. Sister Alegría is an MD herself, and she shared this wry comment during a post- Meeting Zoom discussion on November 8, when MFM celebrated the renewal of our ties with Las Amigas del Señor at the 10:00 Meeting for Worship. Sister Alegría was referring to gaining the trust of the women who come to see her at the pub- lic health clinic where she is a physician and Sister Confianza takes care of the pharmacy. Health education is as important as treating the patients’ illnesses, she explained and providing birth con- Sisters Confianza trol is part of the education for the women in the community. She added that the Catholic priest and Alegría “looks the other way,” pretending not to be aware of the birth control their clinic provides. Covenant for Caring Between MFM & Las Amigas del Señor Celebrated at Meeting for Worship on Sunday, November 8 December Newsletter Contents Earlier that morning, near the end of the 10:00 Meeting for Wor- 1 December Queries ship, Ron Marson and Sisters Alegría and Confianza read aloud in turn our shared covenants, which were made in 2009. -

Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: a Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2018 Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System Breanna Lynne Boppre Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Boppre, Breanna Lynne, "Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3220. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/13568393 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN GENDER, RACE, AND JUSTICE-INVOLVEMENT: -

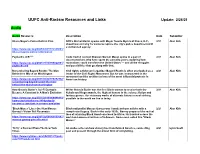

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education Title Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968-2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zq0b64q Journal Berkeley Review of Education, 9(2) Author Patterson, Ryan Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/B89242323 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Available online at http://eScholarship.org/uc/ucbgse_bre Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968–2015 Ryan Patterson William & Mary Abstract This essay explores the history of activism among students of color at the University of Oregon from 1968 to 2015. These students sought to further democratize and diversify curriculum and student services through various means of reform. Beginning in 1968 with the Black Student Union’s demands and proposals for sweeping institutional reform, which included the proposal for a School of Black Studies, this research examines how the Black Student Union created a foundation for future activism among students of color in later decades. Coalitions of affinity groups in the 1990s continued this activist work and pressured the university administration and faculty to adopt a more culturally pluralistic curriculum. This essay also includes a brief historical examination of the state of Oregon and the city of Eugene, Oregon, and their well-documented history of racism and exclusion. This brief examination provides necessary historical context and illuminates how the University of Oregon’s sparse policies regarding race reflect the state’s historic lack of diversity. Keywords: multicultural, activism, University of Oregon Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ryan Patterson. -

5.1 Docket Item: University Program Approval

HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING COMMISSION June 13, 2019 Docket Item #: 5.1 255 Capitol Street NE, Salem, OR 97310 w w w.oregon.gov/HigherEd Docket Item: University Program Approval: University of Oregon, MA in Ethnic Studies. Summary: University of Oregon proposes a new degree program leading to a MA in Ethnic Studies. The statewide Provosts’ Council has unanimously recommended approval. Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC) staff completed a review of the proposed program. After analysis, HECC staff recommends approval of the program as proposed. Staff Recommendation: The HECC recommends the adoption of the following resolution: RESOLVED, that the Higher Education Coordinating Commission approve the following program: MA in Ethnic Studies at University of Oregon. 255 Capitol Street NE, Salem, OR 97310 w w w.oregon.gov/HigherEd Proposal for a New Academic Program Institution: University of Oregon College/School: College of Arts and Sciences Department/Program Name: Department of Ethnic Studies (ES) Degree and Program Title: M.A. in Ethnic Studies (ES) 1. Program Description a. Proposed Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) number. 050299 b. Brief overview (1-2 paragraphs) of the proposed program, including its disciplinary foundations and connections; program objectives; programmatic focus; degree, certificate, minor, and concentrations offered. The Master of Arts degree in Ethnic Studies at the University of Oregon will be awarded to students enrolled in the Ethnic Studies Ph.D. program, which provides advanced interdisciplinary -

Del Campo Ya Pasamos a Otras Cosas--From the Field We Move on to Other Things": Ethnic Mexican Narrators and Latino Community Histories in Washington County, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 9-5-2014 "Del Campo Ya Pasamos a Otras Cosas--From the Field We Move on to Other Things": Ethnic Mexican Narrators and Latino Community Histories in Washington County, Oregon Luke Sprunger Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sprunger, Luke, ""Del Campo Ya Pasamos a Otras Cosas--From the Field We Move on to Other Things": Ethnic Mexican Narrators and Latino Community Histories in Washington County, Oregon" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1977. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1977 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. “Del Campo Ya Pasamos a Otras Cosas— From the Field We Move On to Other Things”: Ethnic Mexican Narrators and Latino Community Histories in Washington County, Oregon by Luke Sprunger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Katrine Barber, Chair Roberto De Anda David Johnson Patricia Schechter Portland State University 2014 © 2014 Luke Sprunger i Abstract This work examines the histories of the Latino population of Washington County, Oregon, and explores how and why ethnic Mexican and other Latino individuals and families relocated to the county. It relies heavily on oral history interviews conducted by the author with ethnic Mexican residents, and on archival newspaper sources. -

Heteronormativity, Critical Race Theory and Anti-Racist Politics

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Winter 1999 Ignoring the Sexualization of Race: Heteronormativity, Critical Race Theory and Anti-Racist Politics Darren Lenard Hutchinson University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Darren Lenard Hutchinson, Ignoring the Sexualization of Race: Heteronormativity, Critical Race Theory and Anti-Racist Politics, 47 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (1999), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/417 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 WINTER 1999 NUMBERI Ignoring the Sexualization of Race: Heteronormativity, Critical Race Theory and Anti-Racist Politics DARREN LENARD HUTCHINSONt INTRODUCTION A fiery dissent rages within the body of identity politics and civil rights theory. The participants in this discourse have lodged fundamental (as well as controversial) charges. Most frequently, these critics argue that the enormous cadre of political activists, progressive lawyers and legal theorists engaged in the particulars of challenging social inequality lack even a basic understanding of how the var- ious forms of subordination operate in society because they fail (or refuse) to realize that systems of oppression do not stand in isolation.! Furthermore, these critics have argued tAssistant Professor, Southern Methodist University School of Law. -

House Bill 2337 Ordered by the House June 7 Including House Amendments Dated June 7

81st OREGON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY--2021 Regular Session A-Engrossed House Bill 2337 Ordered by the House June 7 Including House Amendments dated June 7 Sponsored by Representatives SALINAS, ALONSO LEON, NERON; Representatives BYNUM, NOSSE, PRUSAK, REYNOLDS, RUIZ, SCHOUTEN (Presession filed.) SUMMARY The following summary is not prepared by the sponsors of the measure and is not a part of the body thereof subject to consideration by the Legislative Assembly. It is an editor’s brief statement of the essential features of the measure. Requires [state agencies and third party contractors that collect demographic data on behalf of state agencies to comply with rules adopted by Oregon Health Authority for] advisory committee to Oregon Health Authority and Department of Human Services on collection of data on race, ethnicity, preferred spoken and written languages and disability status to commission study to inventory state agencies’ databases used to compile data on race, ethnicity, language and disability status, ability readiness of data systems to collect data, cost to collect data, needed upgrades to data systems and which data systems are priority for upgrades. Requires report on study to Legislative Assembly by July 1, 2023. Requires authority to [fund] provide grants to operate two mobile health units [to provide linguistically and culturally appropriate services in every region of state based on recommendations of work groups convened by local health authorities. Specifies services to be provided by mobile health units. Requires mobile health units to collect and report to authority specified data that authority then reports to Legislative Assembly] as pilot program to serve communities with histories of poor health outcomes. -

Stovepiped in Silence: the Growing Threat of White Supremacy Extremism in the Pacific Northwest

Concordia University - Portland CU Commons HSEM 494 Practicum/Capstone Project Homeland Security & Emergency Management Spring 6-21-2019 Stovepiped in Silence: The Growing Threat of White Supremacy Extremism in the Pacific Northwest Dacia J. Grayber Concordia University - Portland, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.cu-portland.edu/hsem494 Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons CU Commons Citation Grayber, Dacia J., "Stovepiped in Silence: The Growing Threat of White Supremacy Extremism in the Pacific Northwest" (2019). HSEM 494 Practicum/Capstone Project. 21. https://commons.cu-portland.edu/hsem494/21 This Open Practicum Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Homeland Security & Emergency Management at CU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HSEM 494 Practicum/Capstone Project by an authorized administrator of CU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2018 was the deadliest year on record for domestic extremism violence. How does White Supremacy intersect with this, and what can the public sector do about it? Stovepiped in Silence: The Growing Threat of White Supremacy Extremism in the Pacific Northwest Grayber, Dacia J. Concordia University Executive Summary The purpose of this practicum proposal is to address the growing threat of White Supremacy Extremism (henceforth referred to as “WSE”) in the Portland Metro region and explore the barriers to identifying WSE and obstacles with information sharing. By understanding current conditions and leaning forward with proactive and holistic approaches to education and information sharing, on a local and regional level we may be able to interrupt the cycle of proliferation and interdict future bias and hate crimes in our communities. -

Racial Blindsight: the Absurdity of Color-Blind Criminal Justice

Racial Blindsight: The Absurdity of Color-Blind Criminal Justice * Andrew E. Taslitz In this introductory essay to this symposium, Professor Taslitz argues that the modern criminal justice system is plagued by “racial blindsight.” Analogizing to the physical phenomenon of “blindsight” in which a blind person sees objects but does not know that he sees them, Taslitz maintains that criminal justice system actors often view the world through racial stereotyping or bias but are consciously unaware, or refuse to become aware, of that bias. They see race as a primary guide to thought and action but do not know that they so see the world. Drawing on the too-oft-ignored political writings of Albert Einstein, Taslitz argues that racial blindsight is a particularly morally reprehensible form of self-deception and that persons and institutions are fully capable of removing their blinders. Taslitz identifies a temporal component to racial blindsight, exploring hindsight (ignoring past racial transgressions), foresight (ignoring future foreseeable but avoidable racial harms), and now-sight (ignoring individual and institutional racial biases currently at work), and discusses faux-sight (blatant and obvious efforts to pretend to a non-existent blindness). Taslitz summarizes each of the articles to follow, explaining how they fit within this temporal racial blindsight scheme and what each tells us about how we can open our eyes to promote more candid decisions about race in setting criminal justice policy. I. INTRODUCTION The articles in this Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law symposium address the implications for the criminal justice system of what I will call “racial blindsight.” The term derives from the psychological phenomenon of literal “blindsight,” meaning “seeing without knowing it.”1 English neurologist George Riddoch researched the phenomenon to explain stories of World War I soldiers who were seemingly blinded by head injuries yet dodged bullets.2 All the while 3 the soldiers insisted that they could not see the violence threatening them. -

Police Violence Is Hate Violence

POLICE VIOLENCE IS HATE VIOLENCE Testimonies of Police Brutality from the Streets of Portland From May 31through July 20, 2020 Coalition of PORTLAND UNITED Communities of AGAINST HATE Color Portland United Against Hate & the Coalition of Communities of Color Present: POLICE VIOLENCE IS HATE VIOLENCE: Testimonies of Police Brutality from the Streets of Portland Authored by: Dr. Mira Mohsini Susan Halverson Fonseca, M.S. Rabbi Debra Kolodny Dr. Andres Lopez Photo credit cover photo: Dana Buhl This Photo, credit: Ernesto Fonseca Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Taking Stock of Portland Police Violence 5 3. Testimonies of Police Violence in Portland 6 4. Appendix A: The National and Local Uprisings 14 5. Appendix B: Data on Police Accountability 17 6. Appendix C: ReportHatePDX Database and Methodology 18 7. Appendix D: Advocating for Change 20 8. Appendix E: About Portland United Against Hate and the Coalition of Communities of Color 23 Notes This report is a joint effort by Portland United Against Hate (PUAH) and The Coalition of Communities of Color (CCC). CCC and the authors listed on Page 1 were responsible for analyzing the data in the ReportHatePDX tool, writing this report, and styling it. For more information about these organizations and this collaboration see Appendix E. Content Warning: This report includes graphic images of people wounded by police munitions in Portland. These photos were submitted to PUAH during the timeframe when data for this report were collected. We welcome further visual evidence of the harm caused by police brutality on bodies. Photo Credit: Ernesto Fonseca Executive Summary The murder of George Floyd by police on May 25, 2020, sparked what may be the largest uprising in the history of the United States.