Space Traders for the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur André Douglas Pond Cummings University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law Masthead Logo Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives Faculty Scholarship 2012 Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur andré douglas pond cummings University of Arkansas at little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Judges Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation andré douglas pond cummings, Derrick Bell: Godfather Provocateur, 28 Harv. J. Racial & Ethnic Just. 51 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DERRICK BELL: GODFATHER PROVOCATEUR andrg douglas pond cummings* I. INTRODUCTION Professor Derrick Bell, the originator and founder of Critical Race The- ory, passed away on October 5, 2011. Professor Bell was 80 years old. Around the world he is considered a hero, mentor, friend and exemplar. Known as a creative innovator and agitator, Professor Bell often sacrificed his career in the name of principles and objectives, inspiring a generation of scholars of color and progressive lawyers everywhere.' Bell resigned a tenured position on the Harvard Law School faculty to protest Harvard's refusal to hire and tenure women of color onto its law school -

THE LIFE and LEGAL THOUGHT of DERRICK BELL: FOREWORD Matthew H

Western New England Law Review Volume 36 36 (2014) Article 1 Issue 2 36 (2014) 2014 SYMPOSIUM: BUILDING THE ARC OF JUSTICE: THE LIFE AND LEGAL THOUGHT OF DERRICK BELL: FOREWORD Matthew H. hC arity Western New England University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Matthew H. Charity, SYMPOSIUM: BUILDING THE ARC OF JUSTICE: THE LIFE AND LEGAL THOUGHT OF DERRICK BELL: FOREWORD, 36 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 101 (2014), http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview/vol36/iss2/1 This Introduction is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Review & Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western New England Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATTHEW H. CHARITY WESTERN NEW ENGLAND LAW REVIEW Volume 36 2014 Number 2 SYMPOSIUM BUILDING THE ARC OF JUSTICE: THE LIFE AND LEGAL THOUGHT OF DERRICK BELL MATTHEW H. CHARITY* I know you are asking today, “How long will it take?” Somebody’s asking, “How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?” Somebody’s asking, “When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?” Somebody’s asking, “When will the radiant star of hope be plunged against the nocturnal bosom of this lonely night, plucked from weary souls with chains of fear and the manacles of death? How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?” I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because “truth crushed to earth will rise again.” * Associate Professor of Law, Western New England University School of Law. -

September 1, 2016 TO: the Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: No

September 1, 2016 TO: The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon FR: Angela Wilhelms, Secretary of the University RE: Notice of Board Meeting The Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon will hold a meeting on the date and at the location set forth below. Topics at the meeting will include: a recommendation regarding Dunn Hall; seconded motions and referrals from September 8, 2016, committee meetings; presidential report; presidential assessment report; AY16‐17 tuition and fee setting‐process; “Clusters of Excellence” in focus; federal funding; and an update on UO Portland. The meeting will occur as follows: Thursday, September 8, 2016 – 2:00 pm Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom Friday, September 9, 2016 – 9:30 am Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom The meeting will be webcast, with a link available at www.trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings. The Ford Alumni Center is located at 1720 East 13th Avenue, Eugene, Oregon. If special accommodations are required, please contact Amanda Hatch at (541) 346‐3013 at least 72 hours in advance. BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6227 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403‐1266 T (541) 346‐3166 trustees.uoregon.edu An equal‐opportunity, affirmative‐action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act Board of Trustees of the University of Oregon Public Meeting September 8-9, 2016 Ford Alumni Center, Giustina Ballroom THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8 – 2:00 pm – Convene Public Meeting - Call to order, roll call, verification of quorum - Approval of June 2016 minutes (Action) - Public comment Those wishing to provide comment must sign up advance and review the public comment guidelines either online (http://trustees.uoregon.edu/meetings) or at the check-in table at the meeting. -

2MFM Newsletter 12 2020

DECEMBER QUERIES DECEMBER 2020 How do our social and economic choices help or harm our vulnerable neighbors? The Multnomah Friends Meeting Do we consider whether the seeds of war and the displacement of peoples Monthly have nourishment in our lifestyles and possessions? Newsletter How does the Spirit guide us in our relationship to money? 4312 SE STARK STREET, PORTLAND, OREGON 97215 (503) 232-2822 WWW.MULTNOMAHFRIENDS.ORG FRIENDLY FACES: Sisters Alegría and Confianza of Las Amigas Del Señor Monastery “People will lie to their doctor about three things: smoking, drinking, and sex,” said Sister Alegría of the two-person Las Amigas del Señor Methodist-Quaker Monastery in Limón, Colón, Honduras. Sister Alegría is an MD herself, and she shared this wry comment during a post- Meeting Zoom discussion on November 8, when MFM celebrated the renewal of our ties with Las Amigas del Señor at the 10:00 Meeting for Worship. Sister Alegría was referring to gaining the trust of the women who come to see her at the pub- lic health clinic where she is a physician and Sister Confianza takes care of the pharmacy. Health education is as important as treating the patients’ illnesses, she explained and providing birth con- Sisters Confianza trol is part of the education for the women in the community. She added that the Catholic priest and Alegría “looks the other way,” pretending not to be aware of the birth control their clinic provides. Covenant for Caring Between MFM & Las Amigas del Señor Celebrated at Meeting for Worship on Sunday, November 8 December Newsletter Contents Earlier that morning, near the end of the 10:00 Meeting for Wor- 1 December Queries ship, Ron Marson and Sisters Alegría and Confianza read aloud in turn our shared covenants, which were made in 2009. -

Rethinking the Interest-Convergence Thesis

Copyright 2011 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 105, No. 1 RETHINKING THE INTEREST-CONVERGENCE THESIS Justin Driver* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 149 I. EXAMINING THE INTEREST-CONVERGENCE THESIS ............................................... 157 A. Before the Interest-Convergence Thesis ...................................................... 158 B. The Interest-Convergence Thesis ................................................................ 160 C. Contemporary Views of the Interest-Convergence Thesis ........................... 163 II. ANALYTICAL FLAWS OF THE INTEREST-CONVERGENCE THESIS ............................. 164 A. Interrogating the Composition of Racial Interests ...................................... 165 B. Consistency and Inconsistency of Racial Status .......................................... 171 C. Lack of Agency ............................................................................................ 175 D. Irrefutability ................................................................................................ 181 III. CONSEQUENCES OF THE INTEREST-CONVERGENCE THESIS .................................... 188 A. Constrained Racial Remedies ..................................................................... 189 B. Racial Conspiracy Theory ........................................................................... 192 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................... -

Race and White Privilege Jerome Mccristal Culp Jr

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1999 To the Bone: Race and White Privilege Jerome McCristal Culp Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Culp, Jerome McCristal Jr., "To the Bone: Race and White Privilege" (1999). Minnesota Law Review. 1603. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1603 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Bone: Race and White Privilege Jerome McCristal Culp, Jr.t PROLOGUE Toni Morrison once explained how deeply meaning can be buried in a text. She was asked where in the text of her novel, Beloved, Sethe killed the baby. She answered the questioner by replying confidently that it had happened in a particular chapter, but when she went to look for it there she-the author-could not find it. Meanings can be difficult even for the authors of a text. The same thing is true for the texts written by the multiple authors of a movement. What did we mean and where is a particular event or idea located? These are questions that are difficult for any one person, even someone who, like myself, has at least been a participant in the writing of the text. There may be meanings-unintended meanings-that we who participate are not aware of and it is important to ferret them out. -

SOTO-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (1.424Mb)

CHICAN@ SOCIOGENICS, CHICAN@ LOGICS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHICAN@ PHILOSOPHY: RUPTURING THE BLACK-WHITE BINARY AND WESTERN ANTI-LATIN@ LOGIC A Dissertation by ANDREW CHRISTOPHER SOTO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Tommy Curry Committee Members, Gregory Pappas Amir Jaima Marlon James Head of Department, Theodore George May 2018 Major Subject: Philosophy Copyright 2018 Andrew Christopher Soto ABSTRACT The aim of this project is to create a conceptual blueprint for a Chican@ philosophy. I argue that the creation of a Chican@ philosophy is paramount to liberating Chican@s from the imperial and colonial grip of the Western world and their placement in a Black-white racial binary paradigm. Advancing the philosophical and legal insight of Critical Race Theorists and LatCrit scholars Richard Delgado and Juan Perea, I show that Chican@s are physically, psychologically and institutionally threatened and forced by gring@s to assimilate and adopt a racist Western system of reason and logic that frames U.S. institutions within a Black-white racial binary where Chican@s are either analogized to Black suffering and their historical predicaments with gring@s or placed in a netherworld. In the netherworld, Chican@s are legally, politically and socially constructed as gring@s to uphold the Black-white binary and used as pawns to meet the interests of racist gring@s. Placing Richard Delgado and Juan Perea’s work in conversation with pioneering Chican@ intellectuals Octavio I. Romano-V, Nicolas C. -

Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: a Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2018 Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System Breanna Lynne Boppre Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Boppre, Breanna Lynne, "Intersections Between Gender, Race, and Justice-Involvement: A Mixed Methods Analysis of Women's Experiences in the Oregon Criminal Justice System" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3220. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/13568393 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN GENDER, RACE, AND JUSTICE-INVOLVEMENT: -

Chapter Three Southern Business and Public Accommodations: an Economic-Historical Paradox

Chapter Three Southern Business and Public Accommodations: An Economic-Historical Paradox 2 With the aid of hindsight, the landmark Civil Rights legislation of 1964 and 1965, which shattered the system of racial segregation dating back to the nineteenth century in the southern states, is clearly identifiable as a positive stimulus to regional economic development. Although the South’s convergence toward national per capita income levels began earlier, any number of economic indicators – personal income, business investment, retail sales – show a positive acceleration from the mid 1960s onward, after a hiatus during the previous decade. Surveying the record, journalist Peter Applebome marveled at “the utterly unexpected way the Civil Rights revolution turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to the white South, paving the way for the region’s newfound prosperity.”1 But this observation poses a paradox for business and economic history. Normally we presume that business groups take political positions in order to promote their own economic interests, albeit at times shortsightedly. But here we have a case in which regional businesses and businessmen, with few exceptions, supported segregation and opposed state and national efforts at racial integration, a policy that subsequently emerged as “the best thing that ever happened to the white South.” In effect southern business had to be coerced by the federal government to act in its own economic self interest! Such a paradox in business behavior surely calls for explanation, yet the case has yet to be analyzed explicitly by business and economic historians. This chapter concentrates on public accommodations, a surprisingly neglected topic in Civil Rights history. -

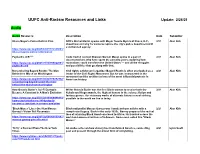

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

“They Tried to Bury Us, but They Didn't Know We Were Seeds.” “Trataron De Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semil

"They Tried to Bury Us, But They Didn't Know We Were Seeds." "Trataron de Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semillas" - The Mexican American/Raza Studies Political and Legal Struggle: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Arce, Martin Sean Citation Arce, Martin Sean. (2020). "They Tried to Bury Us, But They Didn't Know We Were Seeds." "Trataron de Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semillas" - The Mexican American/Raza Studies Political and Legal Struggle: A Content Analysis (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 20:52:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/656744 “THEY TRIED TO BURY US, BUT THEY DIDN’T KNOW WE WERE SEEDS.” “TRATARON DE ENTERRARNOS, PERO NO SABÍAN QUE ÉRAMOS SEMILLAS.” - THE MEXICAN AMERICAN/RAZA STUDIES POLITICAL AND LEGAL STRUGGLE: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Martín Arce ______________________________ Copyright © Martín Arce 2020 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF TEACHING, LEARNING & SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the love and support of my familia, the completion of this dissertation would not have been possible. My brothers Tom Arce, Gil Arce, and Troy Arce are foundational to my upbringing and to who I am today. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education Title Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968-2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zq0b64q Journal Berkeley Review of Education, 9(2) Author Patterson, Ryan Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/B89242323 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Available online at http://eScholarship.org/uc/ucbgse_bre Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968–2015 Ryan Patterson William & Mary Abstract This essay explores the history of activism among students of color at the University of Oregon from 1968 to 2015. These students sought to further democratize and diversify curriculum and student services through various means of reform. Beginning in 1968 with the Black Student Union’s demands and proposals for sweeping institutional reform, which included the proposal for a School of Black Studies, this research examines how the Black Student Union created a foundation for future activism among students of color in later decades. Coalitions of affinity groups in the 1990s continued this activist work and pressured the university administration and faculty to adopt a more culturally pluralistic curriculum. This essay also includes a brief historical examination of the state of Oregon and the city of Eugene, Oregon, and their well-documented history of racism and exclusion. This brief examination provides necessary historical context and illuminates how the University of Oregon’s sparse policies regarding race reflect the state’s historic lack of diversity. Keywords: multicultural, activism, University of Oregon Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ryan Patterson.