Nature Documentaries and Saving Nature: Reflections on the New Netflix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit SK Films: Facebook/Instagram/Youtube: Amber Hawtin @AmazonAdventureFilm Director, Sales & Marketing Twitter: @SKFilms Phone: 416.367.0440 ext. 3033 Cell: 416.930.5524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amazonadventurefilm.com 1 National Press Release: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMAZON ADVENTURE 3D BRINGS AN EPIC AND INSPIRATIONAL STORY SET IN THE HEART OF THE AMAZON RAINFOREST TO IMAX® SCREENS WITH ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY ON APRIL 18th. April 2017 -- SK Films, an award-winning producer and distributor of natural history entertainment, and HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, the acclaimed film production unit of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, announced today the IMAX/Giant Screen film AMAZON ADVENTURE will launch on April 18, 2017 at the World Premiere event at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The film traces the extraordinary journey of naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates - the most influential scientist you’ve never heard of – who provided “the beautiful proof” to Charles Darwin for his then controversial theory of natural selection, the scientific explanation for the development of life on Earth. As a young man, Bates risked his life for science during his 11-year expedition into the Amazon rainforest. AMAZON ADVENTURE is a compelling detective story of peril, perseverance and, ultimately, success, drawing audiences into the fascinating world of animal mimicry, the astonishing phenomenon where one animal adopts the look of another, gaining an advantage to survive. "The Giant Screen is the ideal format to take audiences to places that they might not normally go and to see amazing creatures they might not normally see,” said Executive Producer Jonathan Barker, CEO of SK Films. -

Ca Quarterly of Art and Culture Issue 40 Hair Us $12 Canada $12 Uk £7

c 1 4 0 5 6 6 9 8 9 8 5 3 6 5 US Issue 40 a quarterly of art and culture $12 c anada $12 ha I r u K £7 “Earthrise,” photographed by Apollo 8 on 12 December 1968. According to NASA, “this view of the rising Earth … is displayed here in its original orientation, though it is more commonly viewed with the lunar surface at the bottom of the photo.” FroM DIsc to sphere a permit for the innovative shell, which was deemed Volker M. Welter to be a fire risk, and so the event took place instead in a motel parking lot in the city of Hayward. there, a In october 1969, at the height of the irrational fears four-foot-high inflatable wall delineated a compound about the imminent detonation of the population within which those who were fasting camped. the bomb, about one hundred hippies assembled in the press and the curious lingered outside the wall, joined San Francisco Bay area to stage a “hunger show,” by the occasional participant who could no longer bear a week-long period of total fasting. the event was the hunger pangs, made worse by the temptations of a inspired by a hashish-induced vision that had come to nearby Chinese restaurant. the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand, Symbolically, the raft also offered refuge for planet when reading Paul ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population earth. A photograph in the Whole Earth Catalog from Bomb. the goal was to personally experience the bodi- January 1970 shows an inflated globe among the ly pain of those who suffer from famine and to issue a spread-out paraphernalia of the counter-cultural gather- warning about the mass starvations predicted for the ing, thus making the hunger show one of the earliest 1970s. -

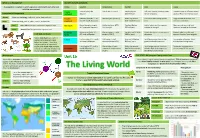

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

Mr. I Mme. President, the Ocean Is the Lifeblood of Our Planet and Mankind. It Covers Over Three-Quarters of the Earth and Accou

·· ..···,·.· i Mr. I Mme. President, The ocean is the lifeblood of our planet and mankind. It covers over three-quarters of the earth and accounts for 97% of the earth's water. It provides more than half of the oxygen we breathe and absorbs over a quarter of the carbon dioxide we produce. About half of the world's popu~ation lives within coastal zones and some 300 million people find their livelihoods in marine fi_sheries. If the oceans are in trouble, so are we. This ~s why we agreed to include "conservation and ~ustainable use of the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development" as Goal 14· of Agenda 2030 and we have ·gathered here today to discuss how to implement it. As a coastal state surrounded by seas on three sides, the Republic .of Korea strongly supports the implementation of Goal 14· in its entirety. We have learned from our past experience of decades that conservation of mari~e ecosystems, fighting against illegal, umeported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and narrowing the capacity gaps for people in LDCs and SIDS are keys to achieving Goal 14. If is because the sustainable development of the ocean is ~riti~ally dependent on. success in these three areas. First, marine ecosystems around the world ar~ at risk of substantial deterioration as oceans face growing threats from pollution, over-fishing, and climate change. Second, IUU fishing puts incredible pressure on fish stock and significantly distorts global markets. Third, capacity gaps prevent LDCs and SIDS from fully utilizing marine resources and hinder th~ir ability to address environmental degradation of the ocean. -

The Plight of Our Planet the Relationship Between Wildlife Programming and Conservation Efforts

! THE PLIGHT OF OUR PLANET fi » = ˛ ≈ ! > M Photo: https://www.kmogallery.com/wildlife/2 = 018/10/5/ry0c9a1o37uwbqlwytiddkxoms8ji1 u f f ≈ f Page 1 The Plight of Our Planet The Relationship Between Wildlife Programming And Conservation Efforts: How Visual Storytelling Can Save The World By: Kelsey O’Connell - 20203259 In Fulfillment For: Film, Television and Screen Industries Project – CULT4035 Prepared For: Disneynature, BBC Earth, Netflix Originals, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, Etc. Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot express enough gratitude to everyone who believed in me on this crazy and fantastic journey; everything you have done has molded me into the person I am today. To my family, who taught me to seek out my own purpose and pursue it wholeheartedly; without you, I would have never taken the chance and moved to England for my Masters. To my professors, who became my trusted resources and friends, your endless and caring teachings have supported me in more ways than I can put into words. To my friends who have never failed to make me smile, I am so lucky to have you in my life. Finally, a special thanks to David Attenborough, Steve Irwin, Terri Irwin, Jane Goodall, Peter Gros, Jim Fowler, and so many others for making me fall in love with wildlife and spark a fire in my heart for their welfare. I grew up on wildlife films and television shows like Planet Earth, Blue Planet, March of the Penguins, Crocodile Hunter, Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, Shark Week, and others – it was because of those programs that I first fell in love with nature as a kid, and I’ve taken that passion with me, my whole life. -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Ipad Educational Apps This List of Apps Was Compiled by the Following Individuals on Behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen

iPad Educational Apps This list of apps was compiled by the following individuals on behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen INNOVATIVE 295 South Marina Drive Brownsville, MN 55919 Home: (507) 750-0506 Cell: (608) 386-2018 EDUCATOR Email: [email protected] Website: http://naomiharm.org CONSULTING Inspired Technology Leadership to Transform Teaching & Learning CONTENTS Art ............................................................................................................... 3 Creativity and Digital Production ................................................................. 5 eBook Applications .................................................................................... 13 Foreign Language ....................................................................................... 22 Music ........................................................................................................ 25 PE / Health ................................................................................................ 27 Special Needs ............................................................................................ 29 STEM - General .......................................................................................... 47 STEM - Science ........................................................................................... 48 STEM - Technology ..................................................................................... 51 STEM - Engineering ................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

How to Save the World STRATEGY for WORLD CONSERVATION

How to save the world STRATEGY FOR WORLD CONSERVATION Robert Allen AX Kogan Page IUCN UNEP WW This book is based on the World Conservation Strategy prepared by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), with the advice, cooperation and financial assistance of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Illustrations: Patrick Virolle Cartoons and cover design: Oliver Duke Copyright ; I UCN-UNEP-WWE 1980 All rights reserved First published 1980 by Kogan Page Limited 120 Pentonvitte Road London NI 9JN Printed in England by MCCorquodale (Newton) Ltd.. Newton-le-Willows, Lancashire. ISBN 0 85038 314 5 (Hb) iSBN (}85038 3153 (Pb) Contents Foreword 7 Preface 9 I. Why the world needs saving now and how it can be done 11 Securing the food supply 33 Forests: saving the saviours 53 Learning to live on planel sea 71 Coming to terms with our fellow species 93 Getting organized: a strategy for conservation 121 Implementing the strategy 145 Foreword Sir Peter Scott Chairman, World Wildlife Fund The World Conservation Strategy, on which this book is based, represents several firsts in nature conservation. it is the first time that governments, non-governmental organizations and experts throughout the world have been involved in preparing a global conservation document. it is the first time that it has been clearly shown how conservation can contribute to the development objectives of governments, industry, commerce, organized labour and the professions. And it is the first time that development has been suggested as a major means of achieving conservation, instead of being viewed as an obstruction to it. -

PAJ77/No.03 Chin-C

AIN’T NO SUNSHINE The Cinema in 2003 Larry Qualls and Daryl Chin s 2003 came to a close, the usual plethora of critics’ awards found themselves usurped by the decision of the Motion Picture Producers Association of A America to disallow the distribution of screeners to its members, and to any organization which adheres to MPAA guidelines (which includes the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences). This became the rallying cry of the Independent Feature Project, as those producers who had created some of the most notable “independent” films of the year tried to find a way to guarantee visibility during award season. This issue soon swamped all discussions of year-end appraisals, as everyone, from critics to filmmakers to studio executives, seemed to weigh in with an opinion on the matter of screeners. Yet, despite this media tempest, the actual situation of film continues to be precarious. As an example, in the summer of 2003 the distribution of films proved even more restrictive, as theatres throughout the United States were block-booked with the endless cycle of sequels that came from the studios (Legally Blonde 2, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, Terminator 3, The Matrix Revolutions, X-2: X-Men United, etc.). A number of smaller films, such as the nature documentary Winged Migration and the New Zealand coming-of-age saga Whale Rider, managed to infiltrate the summer doldrums, but the continued conglomeration of distribution and exhibition has brought the motion picture industry to a stultifying crisis. And the issue of the screeners was the rallying cry for those working on the fringes of the industry, the “independent” producers and directors and small distributors.