John Skinner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

1 P252 John Skinner Papers RECORDS

P252 John Skinner Papers RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: GB1741/P252 Alternative reference number: Title: John Skinner Papers Dates of creation: 1906 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 244 papers Format: Paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: John Skinner Administrative history: John Skinner (31 October 1721 – 16 June 1807) was a Scottish historian and song-writer. Born in Balfour, Aberdeenshire, he was a son of a schoolmaster at Birse, and was educated at Marischal College. Brought up as a Presbyterian, he became an Episcopalian and ministered to a congregation at Longside, near Peterhead, for 65 years. He wrote The Ecclesiastical History of Scotland from the Episcopal point of view, and several songs of which The Reel of Tullochgorum and The Ewie wi' the Crookit Horn are the best known, and he also rendered some of the Psalms into Latin. He kept up a rhyming correspondence with Robert Burns. He died at the home of his son, John Skinner, Bishop Coadjutor of Aberdeen on 16 June 1807. Custodial history: RECORDS’ CONTENT Description: Poetry and plays by John Skinner Appraisal: Accruals: Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives 1 RECORDS’ CONDITION OF ACCESS AND USE Access: open Closed until: Access conditions: Copying: Copying permitted within standard Copyright Act parameters Finding aids: Available in Archive searchroom ALLIED MATERIALS Related material: Publication: Notes: Date of catalogue: November 2011 Ref. Description Dates P252/1 Handwritten sheets, poetry (“Sweet Spring Again”, 1906 “Thurso Braes”, “Lines to Old St Peter’s Church Thurso”, “Thurso Bay”, etc.) and a play “The Captive Queen”, by John Skinner [244 papers] Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives 2 . -

Who Was Bishop Samuel Seabury? by the Rev

Who was Bishop Samuel Seabury? By The Rev. Jay Cayanyang Eternal God, you blessed your servant Samuel Seabury with the gift of perseverance to renew the Anglican inheritance in North America: Grant that, joined together in unity with our bishops and nourished by your holy Sacraments, we proclaim the Gospel of redemption with apostolic zeal; through Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. Samuel Seabury was born on November 30, 1729, in North Groton, Connecticut (present day Ledyard and near Gales Ferry where Bishop Seabury Anglican Church is located). His father, also known by the same name, was the local Congregational minister. Shortly after Seabury was born, his father resigned his pastorate to pursue Holy Orders in the Church of England. While his father was away, Seabury’s mother, Abigail died. After ordination, his father returned to minister in New London, Connecticut under the banner of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Later, the elder Seabury remarried and moved to an assignment in Hempstead, Long Island where under his father’s tutelage as young boy, Samuel Seabury and his brother Caleb prepared for college. As such, Samuel Seabury grew up in home a life that was greatly shaped church life and the Book of Common Prayer. Samuel Seabury studied at Yale College and afterwards returned home to Long Island to study medicine and assist his father in a nearby town as a catechist. Eventually, through the encouragement and support of his father, he went on for further study in Edinburgh, Scotland. -

1789 Journal of Convention

Journal of a Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina 1789 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF A. OF THB PROTESTA:N.T EPISCOPAL CHURCH, IN THE STATES OF NEW YORK, MARYLAND, NEW JERSEY, VIRGINIA, PENNSYLVANIA, AND DELAWARE, I SOUTH CAROLINA: HELD IN CHRIST CHURCH, IN THE CITY OF PHILIlDELPBI.IJ, FROM July 28th to August 8th, 178~o LIST OF THE MEMBER5 OF THE CONVENTION. THE Right Rev. William White, D. D. Bishop of the Pro testant Episcopal Church in the State of Pennsylvania, and Pre sident of the Convention. From the State ofNew TorR. The Rev. Abraham Beach, D. D. The Rev. Benjamin Moore, D. D. lIT. Moses Rogers. -

Message from Fr Andrew Murphy

The Magazine of St Salvador’s Scottish Episcopal Church St Salvador Street, Dundee DD3 7EW E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.stsalvadors.com June 2021 Far be it from me to glory except in the cross of Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me and I to the world. Galatians 6:14 Message from Fr Andrew Murphy SSC (Tel.: 07920 596990) Corpus Christi and Petertide My friends in Christ, the beginning and the end of this coming month of June see two important liturgy days, firstly Corpus Christi and the second we call Petertide or Peter’s tide being the Sunday nearest to 29th June which is the festival day of SS Peter and Paul. At Corpus Christi, meaning the body and blood of Christ, we celeb- rate His presence in the Eucharist, normally four days after Pentecost but nowadays sometimes on the following Sunday. The Petertide season in- cludes the days before and around that feast and is special in the Anglican calendar for it is in the days around then that most deacons and priests are ordained into the church. The two feasts are not unconnected, for it is only ordained priests who can celebrate Mass and consecrate the sac- red bread and wine which becomes Christ’s body and blood. When Christ handed Peter the footsteps of St Peter who himself wrestled with fol- keys of Heaven, and declared that he was “the lowing Christ and later endured hardships to be rock” upon which his church was to be built, he faithful to his master. -

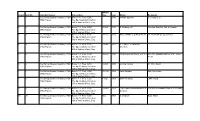

Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Month/ Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 the Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- 1796) Papers

Month/ Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 1740 William Spencer S. Seabury, Sr. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 2 2 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Oct 1753 S. Seabury, Sr. Thomas Sherlock, Bp. of London 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 3 3 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 24-Dec 1755 Moses Mathers & Noah Wells Dr. Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 4 4 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Jan 1757 S. Clowes, Jr. and Wm. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Sherlock Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 5 5 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 28-Feb 1757 Philip Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) Rev. Mr. Obadiah Mather & Mr. Noah 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Wells Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 6 6 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 30-Oct 1760 Archbp. Secker Dr. Wm. Smith 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 7 7 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 16-Feb 1762 Jane Durham Mrs. Ann Hicks 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 8 8 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 4-Sep 1763 Sam'l Seabury John Troup 1796) Papers The Bp. -

Rev John Skinner

‘My father what? Had a duel? He’s in his seventies! Silly man!’ so might antiquarian, James Byres of Tonley have exclaimed when he was brought word about the unseemly quarrel occasioned by Byres Snr. Patrick Byres was an Irish Jacobite, born in Dublin, 1713. In 1741 he married Janet Moir of Stoneywood and became a Burgess of Guild in Aberdeen, yet his political leanings and hot Celtic temper seem to have constantly landed Patrick in trouble. His first problem was his involvement in the Forty-Five Rebellion, fighting on Bonnie Prince Charlie’s side as Major Byres in Stoneywood’s regiment. Escaping Culloden, Patrick’s ally, Gordon of Cluny hid him in his castle until he and his family escaped to France. He managed to hang on to Tonley by the clever suggestion that his English name was Peter, thus he was not Patrick Byres the rebel. While his youngest sons, William and John developed military careers in the Navy and Royal Engineers respectively and second son, Robert took up merchant interests in Prussia, the eldest, James, became something of a tour guide. He embraced antiquarian studies in Rome and became the go-to ex-pat for visiting Scots gentlefolk on their ‘grand tours’ of Europe. Meanwhile, his father returned to Tonley, Mrs Byres hoping her husband’s adventures were over. But, due to Janet’s nephew, James Abernethy of Mayen, Patrick was to be the centre of unwanted attention once more in 1763. A traditional ballad is dedicated to the incident in which John Leith of Leith Hall, Rhynie was murdered by Abernethy after an argument in the New Inn, Aberdeen. -

CRUCIS Magazine of St

CRUCIS Magazine of St. Salvador’s Scottish Episcopal Church Dundee June 2018 “Far be it from me to glory except in the cross of Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me and I to the world.” Galatians 6:14 In the Beginning… talking about mission so much. Less talk, more action. Just do it. The new Bishop will have a lot of work to do. To start with, there will be many personal and Our greatest need is for new hearts and a new professional adjustments to be made. Then there spirit. Only God can reorient us to do what He will be sorting through the avalanche of infor- wants us to do and what needs to be done. mation that will suddenly cascade upon him. Evangelism must therefore begin with our own Demands for time and consideration are likely conversion. We need actively to be seeking to to come from every quarter. Money and clergy become the best we can be. No one is too old or recruits need to be found. And then there will be to young to start. All of us can play a part. Be- all those other problems to fix at the diocesan fore we can reach out to others, we must first and provincial levels. It will be a dizzying, dis- reach out to God ourselves in every way avail- orienting time for our new Father-in-God. He able to us. And then we must reach out to the will need our prayers. world, starting here and now. What our new Bishop will not need is our unre- Do we really see the world as a field ripe for alistic expectations. -

The Skinner Kinsmen

The Skinner Kinsmen: Descendants of Thomas Skinner of Malden, MA Natalie R. Fernald Washington, DC 1926 THE SKINNER KINSMEN. DESCENDANTS OF THOMAS SKINNER. 1. Sergeant THOMAS SKINNER (1), born in Eng land, 1617, came to America from Chichester between 1649 and 1651. He married, first, in England, Mary, she died April 9, 1671; married, second, about 1680, Lydia, daughter of Daniel and Joanna Sh_pardson, of Malden, Mass., and widow of Thomas Call. Lydia was baptized July 24, 1637, married Thomas Call July 22, 1657, he died Nov. 1678. Thomas Skinner was admit ted Freeman at Malden, May 18, 1653; he died March 2, 1703-4, Lydia died Dec. 17, 1723. (Gravestone at Mal den). Children: 2. Thomas (2), bp. Subdeanarie Parish, Chichester, England, July 25, 1645, m. l\iary, daughter of Rich ard and Mary Pratt, of Charlestovvn, l\Iass. She ,vas born Sept. 9 or 30, 1643. They removed to Col chester, Conn., ,vhere she di2d March 26, 1704. 3. John (2), bp. North l\Iundham, England, April 19, 1647. 4. Abraham (2), bp. Pallant Parish, Chichester, Eng land, Sept. 29, 1649, m. Hannah. He died between 1693 and 1698. She died Jan. 14, 1725-6. THE SKINNER KINSMEN. CONTEMPORARY RECORDS. From \Vyman, Charlestown Genealogies and Estates. Thomas Skinner ( 1), Malden, victualler, from Chichester, County of Sussex, England. Estate.-Will: Testamentary document, no date, acknowledged Feb. 2, 1693-4, devised house to son Abraham, and he to pay Lydia and son Thomas. His ( Thomas ( 1)) maintenance to be provided, recorded Dec. 9, 1696 (p. 869). From Corey, History of Malden. -

Profile of the United Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney

Profile of the United Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney May 2017 0 1 Contents Page No. Achievements and Challenges 3 Aberdeen beyond the Present 5 The Diocesan Mission Structures 8 The Charges & Congregations of the Diocese 11 • Aberdeen City Area • Around Aberdeen • North & North East Area • Central Buchan • Donside & Deeside Area • Orkney • Shetland • Religious Communities • Area Groups • Map of the Diocese The Diocesan Administration 32 • Diocesan Office • Diocesan Personnel • Diocesan Statistics The Finances of the Diocese 36 • Overview • Extracts from Diocesan Treasurer's report 2016 • Statement of Financial Activities for the year ended 31 October 2016 • Balance Sheet at 31 October 2016 • Budgets for the period 2016 – 2019 The Bishop's Remuneration 40 • The Bishop’s House • Bishop’s Stipend & Pension The Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney 42 • General Information The Constitution of the Diocese 46 The Minutes of the Diocesan Synod 2016 53 The Seven Dioceses of the Scottish Episcopal Church 60 • Map • Provincial Summary 2 Achievements and Challenges The United Diocese of Aberdeen and Orkney is a thriving, vibrant and forward looking Diocese which comprises a mix of urban, rural and island parishes, some in areas of social deprivation, but most of which are situated in beautiful countryside and surroundings. Over recent years the Diocese, especially through its charges and people, has made progress in working in partnership with others, in its development of being church for the North East and in its approach to specialist and newer forms of both mission and ministry. We believe that this provides a springboard for real developments for Christianity in the North East under the leadership of a new Bishop. -

Synod 2017 Information Booklet Web.Pdf

The Anglican Church in the Diocese of Trinidad and Tobago INFORMATION BOOKLET The 145th Session The 145th Session of the Annual Synod of the Annual Synod of the Annual Synod Wednesday 7th June to Theme: Saturday 10th June, 2017 “Nurturing Boys, Forming Men for Couva Banquet and Conference Centre God’s Kingdom” Couva Shopping Complex 145th Annual Meeting of Synod Stewardship: Nurturing Boys, Forming Men for God’s Kingdom Contents Notice of Meeting …………………………………………………………………………….2 Agenda ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Thursday June 8, 2017 ........................................................................................................... 3 Friday June 9, 2017 ................................................................................................................ 3 Saturday June 10, 2017 .......................................................................................................... 4 MINUTES OF THE 144th ANNUAL MEETING OF SYNOD ........................................ 5 -25 ELECTION INFORMATION .......................................................................................... 26-27 DC NOMINEES TO BOARD OF FINANCE………………………………………… 28-30 REGULATION 27: Of Standing Orders ............................................................................. 31-33 RULES OF ORDER .......................................................................................................... 34-36 MEMBERS OF SYNOD 2017: -

A Walk Along the Antonine Wall in 1825: the Travel Journal of the Rev John Skinner

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 133 (2003), 205–244 A walk along the Antonine Wall in 1825: the travel journal of the Rev John Skinner Lawrence Keppie* ABSTRACT In 1825 the Rev John Skinner, an Anglican clergyman from Camerton in Somerset, walked the length of the Antonine Wall from east to west, as part of an extensive Scottish tour. He recorded his observations at length in a journal and prepared daily a series of pencil sketches which constitute an invaluable record of the monument at a fixed date. His sketches include sculptures and inscriptions subsequently lost, and a few sites otherwise unrecorded. He also visited the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow in order to view its collection of Roman stones. INTRODUCTION After his return to Camerton, the journals were transcribed by his brother, in a neat hand Over a five-day period in September 1825 the that can be easily read today (in contrast to Rev John Skinner of Camerton in Somerset, Skinner’s own handwriting which can be near Bath, traversed the Antonine Wall on ffi foot from east to west, as part of an extensive di cult to decipher). Sometimes the seeming ‘northern tour’ which took him as far north as peculiarities of punctuation result from clauses Inverness. Skinner had travelled from the being associated with the wrong sentence, south-west of England with his son Owen, perhaps by his brother when the journals were whom he left in Edinburgh owing to illness. transcribed. His brother mistranscribed indi- On completing his Highland peregrination, he vidual words, especially proper names, or left was reunited with his son, now restored to gaps where the handwriting had defeated him.