Civil Society Mapping Mon State, Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao

ICS TRAVEL GROUP is one of the first international DMCs to open own offices in our destinations and has since become a market leader throughout the Mekong region, Indonesia and India. As such, we can offer you the following advantages: Global Network. Rapid Response. With a centralised reservations centre/head All quotation and booking requests are answered office in Bangkok and 7 sales offices. promptly and accurately, with no exceptions. Local Knowledge and Network. Innovative Online Booking Engine. We have operations offices on the ground at every Our booking and feedback systems are unrivalled major destination – making us your incountry expert in the industry. for your every need. Creative MICE team. Quality Experience. Our team of experienced travel professionals in Our goal is to provide a seamless travel experience each country is accustomed to handling multi- for your clients. national incentives. Competitive Hotel Rates. International Standards / Financial Stability We have contract rates with over 1000 hotels and All our operational offices are fully licensed pride ourselves on having the most attractive pricing and financially stable. All guides and drivers are strategies in the region. thoroughly trained and licensed. Full Range of Services and Products. Wherever your clients want to go and whatever they want to do, we can do it. Our portfolio includes the complete range of prod- ucts for leisure and niche travellers alike. ICS TRAVEL ICSGROUPTRAVEL GROUP Contents Introduction 3 Tours 4 Cruises 20 Hotels 24 Yangon 24 Mandalay 30 Bagan 34 Mount Popa 37 Inle Lake 38 Nyaung Shwe 41 Ngapali 42 Pyay 45 Mrauk U 45 Ngwe Saung 46 Excursions 48 Hotel Symbol: ICS Preferred Hotel Style Hotel Boutique Hotel Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao Lahe INDIA INDIA Myitkyina CHINA CHINA Bhamo Muse MYANMAR Mogok Lashio Hsipaw BANGLADESHBANGLADESH Mandalay Monywa ICS TRA VEL GR OUP Meng La Nyaung Oo Kengtung Mt. -

Eligible Voters Per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency 2015 Elections

Myanmar Information Management Unit Eligible Voters per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency 2015 Elections 90° E 95° E 100° E This map shows the variation in the number of registered voters per township according to UEC data. Nawngmun BHUTAN Puta-O Machanbaw Nanyun Khaunglanhpu Sumprabum Tsawlaw Tanai Lahe Injangyang INDIA Hpakant KACHIN Hkamti Chipwi Hpakant Waingmaw Lay Shi Mogaung N N ° CHINA ° 5 Homalin Myitkyina 5 2 Mohnyin 2 Momauk Banmauk Indaw BANGLADESH Shwegu Bhamo PaungbySinAGAING Katha Tamu Pinlebu Konkyan Wuntho Mansi Muse Kawlin Tigyaing Tonzang Mawlaik Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Mabein Kyunhla Thabeikkyin Kunlong Tedim Manton Hopang Kalewa Hseni Kale Kanbalu Mongmit Taze Namtu Hopang Falam Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Mingin Ye-U Mogoke Pangwaun Thantlang Khin-U Tabayin Kyaukme Shwebo Singu Tangyan Narphan Kani Hakha Budalin Wetlet Nawnghkio Mongyai Pangsang Ayadaw Madaya Hsipaw Yinmabin Monywa Sagaing Patheingyi Gangaw Salingyi VIETNAM Pale Myinmu Mongyang Matupi Chaung-U Ngazun Pyinoolwin Kyethi Myaung Matman CHIN Tilin Myaing Sintgaing Mongkaung Monghsu Mongkhet Tada-U Kyaukse Lawksawk Mongla Pauk Myingyan Paletwa Mindat Yesagyo Natogyi Saw Myittha SHAN Pakokku Hopong Laihka Maungdaw Ywangan Kunhing Mongping Kengtung Mongyawng MTaAunNgthDa ALWAundYwin Buthidaung Kanpetlet Seikphyu Nyaung-U Mahlaing Pindaya Loilen Kyauktaw Nansang Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Meiktila Thazi Taunggyi Chauk Salin Kalaw Mongnai Ponnagyun Pyawbwe Tachileik Minbya Monghsat Rathedaung Mrauk-U Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Nyaungshwe RAKHINE Natmauk Yamethin Pwintbyu Mawkmai -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

Release Lists English (4-Jun-2021)

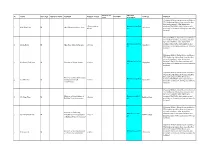

Section of Current No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Plaintiff Address Remark Law Condition Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were 1-Feb-21 and 10- Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 1 Salai Lian Luai M Chief Minister of Chin State Chin State Feb-21 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 2 (U) Zo Bawi M Chin State Hluttaw Speaker 1-Feb-21 Chin State 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 3 (U) Naing Thet Lwin M Minister of Ethnic Affairs 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Natural Resources Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 4 (U) Ohn Win M and Environmental 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw 21 ministers in the states and regions were also Conservation detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Social Affairs of Released on 2 Feb detained. -

Thailand/Myanmar : UNHCR Offices in South East Region July 2019

Thailand/Myanmar : UNHCR Offices in South East Region July 2019 Yamethin Natmauk Taunggyi Tachileik Monghsat Myothit Mongpan Nyaungshwe Nay Pyi Taw-Tatkon Hsihseng Pinlaung Mawkmai Langkho Mongton Mandalay Shan Taungdwingyi Chiang Rai Nay Pyi Taw-Pyinmana Loikaw Pekon Nay Pyi Taw-Lewe Loikaw Sinbaungwe Demoso Shadaw Ban Mai Nai Soi Aunglan Magway Yedashe Hpruso Mae Hong Son Kayah Phayao Bawlakhe Thandaunggyi Paukkhaung Taungoo Ban Mae Surin Hpasawng Mae Hong Son Oktwin Chiang Mai Nan Paungde Mese Thegon Nattalin Phyu Kyaukkyi Zigon Gyobingauk Lampang Okpho Kyauktaga Phrae Bago Lamphun Letpadan Hpapun Minhla Nyaunglebin Monyo Mae Ra Ma Luang Shwegyin Daik-U Mae La Oon Uttaradit Thayarwady Hinthada Bago Zalun Waw Taikkyi Kyaikto Loei Shwepyithar Danubyu Bilin Hlegu Thanatpin Sukhothai Hmawbi Hlaingbwe Thingangyun Kayin Mae La Nyaungdon Thanlyin Kawa Htantabin Hlaing Thaton Phitsanulok Kayan Hpa-An Mingaladon Insein Thongwa Hpa-An Maubin Twantay Yangon Tak Pantanaw Thaketa Dala Paung Mae Sot Kawhmu Kyauktan Mingalartaungnyunt Kyaiklat Dagon Myothit (South) Kawkareik Kungyangon Dagon Myothit (East) Kamphaeng Phet Bogale Dagon Myothit (Seikkan) Mawlamyine Chaungzon Dedaye Dagon Myothit (North) Seikgyikanaungto Kyaikmaraw Umpiem Phichit Myawaddy Pyapon Mudon Phetchabun ANDAMAN SEA Thanbyuzayat Kyainseikgyi Nu Po Nakhon Sawan Legend Mon UNHCR Offices Ye Uthai Thani Temporary Shelters Ban Don Yang Chai Nat State Boundary Lop Buri Sing Buri Township Boundary Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Yebyu Suphan Buri Ang Thong UNHCR Yangon Kanchanaburi Saraburi 287 Pyay Road, Myaynigone, Sanchaung Township, Yangon Tel:01-524022, 524024, 524025, 524026 Nakhon Nayok UNHCR Bangkok 3rd Floor, UN Building, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkhunprom, Pranakorn, Bangkok 10200 Pathum Thani Email: [email protected] Launglon Nakhon Pathom Bangkok Metropolis Dawei Nonthaburi Chachoengsao Thayetchaung Bangkok Tanintharyi Tham Hin Samut Prakan Samut Sakhon Ratchaburi Samut Songkhram Palaw Chon Buri Tanintharyi Phetchaburi Rayong UNHCR Information Management Unit - Mae sot Base layer provided by MIMU. -

Flash Alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 30 September Cases Thursday, October 1, 2020

Flash alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 30 September Cases Thursday, October 1, 2020 Yesterday evening at 20:00 hrs, 946 new Covid-19 cases were identified, i.e. 12,999 cases since the beginning of the second wave on 16 August. Since the beginning of the pandemic in March, 13,373 people have been contaminated in Myanmar, and a total of 310 people have died of Covid-19. At 16:30 Hrs, the MoHS released the spatial breakdown of those 946 cases: 786 in Yangon Region, 68 in Ayeyarwaddy Region, 25 in Rakhine State, 21 in Bago Region, 19 in Sagaing Region, 7 in Mandalay Region, 6 in Kachin State, 5 in Tanintharyi Region, 4 in Shan State, 3 in Mon State, 1 in Kayin State, 1 in Nay Pyi Taw. Since 16 August, 9,765 cases have been reported in Yangon Region. Out of the 786 new cases from yesterday, 15 cases did not come along with any detail about their townships; this information will be released later. Usually, a handful of townships stand out as the most massive surges in the last 24 hours; but yesterday, 9 townships had comparable growth, ranging from 46 to 57 new cases. Insein is the most-affected township in Yangon, ahead of Thingangyun, South and North Okkalapa, Tarmwe, Hlaing, Hlaing Thayar, Thaketa and Mingaladon Townships. Imported cases N° of new cases on 30 N° of total cases Township Local cases from abroad September since 16 August Ahlone 5 5 126 Bahan 7 7 200 Botahtaung 46 46 172 Dagon 8 8 190 Dagon Myothit (East) 14 14 194 Dagon Myothit (North) 9 9 193 Dagon Myothit (South) 11 11 210 Dagon Seikkan 15 15 112 Dala 56 56 -

Recent Fatality List for June 10, 2021 (English)

Date of Deceased Place of No. Name Sex Age Father's name Organization Home Adress Township States/Regions Remarks Incident Date Incidents In another incident, 32 year old 75 street, Na Pwar (aka) Ko Nyi Ko Na Pwar (a.k.a Ko Ko Oo), 1 M 32 U Hla Ngwe 08-Feb-21 08-Feb-21 Civilian Mandalay between 37 and Mahaaungmye Mandalay Region Nyi Oo died after a car intentionally hit 38 street him at night in Mandalay. On February 9, peaceful anti- coup protests in Naypyitaw were suppressed using a water Hlaykhwintaung, cannon, rubber bullets and live Lower Mya Thwate Thwate ammunition resulting in four 2 F 19 unknown 09-Feb-21 19-Feb-21 Civilian NayPyi Taw Paunglaung Zeyathiri Naypyidaw Khaing people being injured. Among Hydro Power them was Ma Mya Thawe Thawe Project Khaing, 21-years old, who, on 19 February later died from gunshot wounds to the head. On 15 February evening, 18-year old Maung Nay Nay Win Htet Myeik, Tanintharyi was beaten on his head to death 3 Nay Nay Win Htet M 18 unknown 15-Feb-21 15-Feb-21 Civilian Tanintharyi Toe Chal Ward Myeik Region while guarding a waroad Region, security in Myeik, Tanintharyi Region. In Mandalay, a shipyaroad raid turned violent on Saturoaday when security forces opened fire Thet Naing Win @ Min Kannar road, 4 M 37 U Maung San 20-Feb-21 20-Feb-21 Civilian near 41 street Mahaaungmye Mandalay Region on demonstrators trying to stop Min Mandalay City the arrest of workers taking part in the growing anti-coup movement. -

Military Columns Participate in Full-Dress Rehearsal for 76Th Anniversary of Armed Forces Day Parade

ETHNIC RIGHTS STRATEGY KEY TO ENSURING PEOPLE ENJOY EQUAL RIGHTS PAGE-8 (OPINION) Vol. VII, No. 343, 13th Waxing of Tabaung 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Thursday, 25 March 2021 Military columns participate in full-dress rehearsal for 76th Anniversary of Armed Forces Day Parade Vice-Chairman of the State Administration Council Deputy Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Vice-Senior General Soe Win is viewing the full-dress rehearsal for the 76th Anniversary of Armed Forces Day Parade, yesterday. MILITARY columns, which will Oo marched into the parade senior military officers including the military columns. After the Navy) and aircraft from the Tat- participate in the parade of the ground on the parade agenda by Chairman of the Leading Com- parade, the Vice-Senior General madaw (Air) participated in the 76th Anniversary of Armed Forces singing marching songs in chorus mittee for Observance of the attended to the needs in coordi- parade rehearsal. Those mem- Day that falls on 27 March, took to the accompaniment of the Tat- Armed Forces Day Chief of the nation with officials. bers wore badges and uniforms part in the full-dress parade at madaw military band. Together General Staff (Army, Navy and Officers and other ranks used by the Myanmar Tatmad- Nay Pyi Taw parade ground yes- with Vice-Chairman of the State Air) General Maung Maung Aye, from Tatmadaw (Army, Navy and aw in successive eras from the terday morning. Administration Council Deputy Chairman of the Management Air) and Myanmar Police Forces, independence struggle to 2020, Anawyahtar, -

Mimu791v02 111018 UNOPS HIV Townships Shown by Service Activities A1.Mxd

Myanmar Information Management Unit UNOPS PR-GFATM Townships shown by Service Delivery Area (Year 1) HIV Project Townships 90°0'E 92°0'E 94°0'E 96°0'E 98°0'E 100°0'E 102°0'E 104°0'E Nawngmun 28°0'N 28°0'N Bhutan Puta-O Machanbaw Ü Nanyun Khaunglanhpu Tanai Sumprabum Tsawlaw Lahe Injangyang 26°0'N 26°0'N Myitkyina(4) Chipwi Hkamti (ART,HBC, India MMT,TH ) China Hpakan(1) (PMCT ) Waingmaw(2) (MMT,PMCT ) Lay Shi Mogaung(2) (MMT,PMCT ) Mohnyin(1) Homalin (PMCT ) Banmauk Momauk Indaw Shwegu Katha(1) Bhamo(2) (PMCT ) (ART,MMT ) Tamu(1) Paungbyin (PMCT ) Pinlebu Wuntho Muse(3) Mansi (HR, ART,MMT ) Konkyan 24°0'N 24°0'N Tigyaing Tonzang Kawlin Mawlaik Namhkan(1) Laukkaing Mabein (MMT ) Kutkai(2) Bangladesh (HR, MMT ) Kyunhla Thabeikkyin Manton Kunlong Tedim Kalewa(1) Hseni (PMCT ) Kale(2) Kanbalu Hopang (ART,HBC ) Mongmit Taze Namtu Falam Lashio(3) (ART,MMT,TH, Namhsan Mongmao Mingin Mogoke(1) ART,TH ) Pangwaun Ye-U (PMCT ) Khin-U Thantlang Tabayin(1) Kyaukme(2) (PMCT ) Man Man Shwebo(2) (PMCT,TCP ) Tangyan (ART,HBC ) Singu(1) Hseng Kani (PMCT ) Namphan Hakha(1) Budalin(1) (PMCT ) (PMCT ) Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Hsipaw(1) Ayadaw Madaya(1) (PMCT ) Monywa(2) (PMCT ) Yinmabin Gangaw (ART,TH, Sagaing(1) ART,TH ) Matman Pale(1) Myinmu (PMCT ) Salingyi Pyinoolwin(1) Mongyang 22°0'N (PMCT ) Chaung-U(2) (ART ) 22°0'N (PMCT,TCP ) Kyethi Matupi Ngazun(1) Vietnam Tilin Myaung Monghsu (PMCT ) Sintgaing(1) Mongkaung Myaing(1) (PMCT ) Tada-U Mongkhet (PMCT ) Yesagyo Kyaukse(2) Myingyan(4) (ART,PMCT ) (ART, ART,BCC, Lawksawk Mongla Mindat Pauk HBC, ART,TH -

Burma Briefer

Λ L T S E Λ N B U R M A BN 2014/2003: Edited September 19, 2014 DEVELOPMENTS AFTER THE 2013 UNGA RESOLUTION The Burmese authorities have failed to implement most of the recommendations from previous United Nations General INSIDE Assembly (UNGA) resolutions, in particular Resolution 1 2015 ELECTIONS 68/242, adopted in 2013. In some areas, the situation has 2 MEDIA FREEDOMS RESTRICTED deteriorated as a result of deliberate actions by the 3 ARBITRARY HRD ARRESTS authorities. This briefer summarizes developments on the 4 OTHER HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS ground with direct reference to key paragraphs of the 4 Torture and sexual violence resolution. 5 Land confiscation 5 WAR AND PEACE TALKS The authorities have either failed or refused to protect 6 PERSECUTION OF ROHINGYA vulnerable populations from serious human rights violations, 6 Discriminatory legislation or pursued essential legislative and institutional reforms, effectively blocking Burma’s progress towards genuine 6 Pre-existing laws and policies democracy and national reconciliation. This has been partly 7 Failure to respond to communal violence due to an assumption that the UNGA resolution will either be 7 Hate speech and incitement to violence canceled or severely watered down as a trade-off for smaller 7 1.2 MILLION PEOPLE EXCLUDED concessions. FROM CENSUS 8 SITUATION DIRE IN ARAKAN STATE So far, 2014 has been marred by an overall climate of APPENDICES impunity that has seen a resurgence of media repression, the ongoing sentencing of human rights defenders, an increase in a1 I: 158 new arrests and imprisonments the number of land ownership disputes, and ongoing attacks a14 II: Contradictory ceasefire talks on civilians by the Tatmadaw in Kachin and Shan States a15 III: 122 clashes in Kachin, Shan States amid nationwide ceasefire negotiations. -

Burma Page 1 of 30

2008 Human Rights Report: Burma Page 1 of 30 2008 Human Rights Report: Burma BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Burma, with an estimated population of 54 million, is ruled by a highly authoritarian military regime dominated by the majority ethnic Burman group. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, was the country's de facto government. Military officers wielded the ultimate authority at each level of government. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a general parliamentary election, but the regime continued to ignore the results. The military government controlled the security forces without civilian oversight. The regime continued to abridge the right of citizens to change their government and committed other severe human rights abuses. Government security forces allowed custodial deaths to occur and committed other extrajudicial killings, disappearances, rape, and torture. The government detained civic activists indefinitely and without charges. In addition regime-sponsored mass-member organizations engaged in harassment, abuse, and detention of human rights and prodemocracy activists. The government abused prisoners and detainees, held persons in harsh and life-threatening conditions, routinely used incommunicado detention, and imprisoned citizens arbitrarily for political motives. The army continued its attacks on ethnic minority villagers. Aung San Suu Kyi, general secretary of the National League for Democracy (NLD), and NLD Vice-Chairman Tin Oo remained under house arrest. The government routinely infringed on citizens' privacy and restricted freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, religion, and movement. -

Kyongadat Model Village in Thanbyuzayat Tsp, Mon State, Puts 125 Acres Under Rubber

Established 1914 Volume XV, Number 52 8th Waning of Nayon 1369 ME Thursday, 7 June, 2007 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Stability of the State, community peace * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round * Uplift of the morale and morality of development of other sectors of the economy as well and tranquillity, prevalence of law and the entire nation * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic order * Uplift of national prestige and integ- system * National reconsolidation rity and preservation and safeguard- * Development of the economy inviting participation in * Emergence of a new enduring State ing of cultural heritage and national terms of technical know-how and investments from Constitution character sources inside the country and abroad * Building of a new modern developed * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept * Uplift of health, fitness and education nation in accord with the new State in the hands of the State and the national peoples Constitution standards of the entire nation Kyongadat model village in Thanbyuzayat Tsp, Mon State, puts 125 acres under rubber NAY P YI T AW, 6 June—Member of the State Peace and Development Council Lt-Gen Maung Bo of the Ministry of Defence accompanied by Chairman of Mon State PDC Commander of South-East Command Maj-Gen Thet Naing Win attended the collective growing of rubber at Kyongadat model village in Thanbyuzayat Township on 4 June morning. They planted rubber saplings at the designated places and viewed the growing of rubber by farmers and local people.