The Cincinnati Zoological Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files

City of Cincinnati Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files File Cabinet 1 Drawer 1 1. A3MC Proposed Merger Cincinnati Enquirer and Post 1977 and 1978 2. No Folder Name 3. A33 Cincinnati Post 4. A33 Cincinnati Enquirer 5. A33 Sale of the Enquirer 6. A33 Cincinnati Kurier 7. A33 Newspapers and Magazines 8. Navy 9. A34 Copying, Processes, Printing, Mimeographing, Microfilming 10. A34C Carts, Codes Cincinnati 11. A45Mc General Public Reports (Cincinnati City Bulletin Progress) 12. A49Mc Name- Cincinnati’s “Cincinnati and Queen City of the West 2” 13. Cincinnati- Nourished and Protected by the River that Gave It by William H. Hessler 14. Cincinnati-Name-Flower-Flag-Seal-Key-Songs 15. A49so Ohio 16. Last Edition Printed by the Cincinnati Time-Star July 19, 1958 17. Ohio Sesquicentennial Celebration 18. A6 O/Ohio History-Historical Societies 19. A6mc General Information (I) Cincinnati 20. General Information 2 Cincinnati 21. Cincinnati Geological Society 22. Cincinnati’s Birthdays 23. Pictures of Old Cincinnati 24. A6mc Historical Society- Cincinnati 25. A6mc Famous Cincinnati Families (Enquirer Series 1980) 26. A6mc President Reagan’s Visit to Cincinnati 12/11/81 27. A6mc Pres. Fords Visit to Cincinnati July 1975 and October 28, 1976 28. A6c Famous People Who have Visited Cincinnati 29. A Brief Sketch of the History of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce 30. Cincinnati History 31. History of Cincinnati 1950? 32. Cincinnati 1924 33. Cincinnati 1926 34. Cincinnati 1928 35. Cincinnati 1930 36. Cincinnati 1931 37. Cincinnati 1931 38. Cincinnati 1932 39. Cincinnati 1932 40. Cincinnati 1933 41. Cincinnati 1935 42. -

VOLUME 17 • NUMBER 3 • FALL 2017 Ohio Valley History Is a OHIO VALLEY STAFF John David Smith Gary Z

A Collaboration of The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky, Cincinnati Museum Center, and the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio. VOLUME 17 • NUMBER 3 • FALL 2017 Ohio Valley History is a OHIO VALLEY STAFF John David Smith Gary Z. Lindgren University of North Carolina, Mitchel D. Livingston, Ph.D. collaboration of The Filson Editors Charlotte Phillip C. Long Historical Society, Louisville, LeeAnn Whites David Stradling Julia Poston Kentucky, Cincinnati Museum The Filson Historical Society University of Cincinnati Thomas H. Quinn Jr. Matthew Norman Nikki M. Taylor Anya Sanchez, MD, MBA Center, and the University of Department of History Texas Southern University Judith K. Stein, M.D. Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio. University of Cincinnati Frank Towers Steve Steinman Blue Ash College University of Calgary Carolyn Tastad Anne Drackett Thomas Cincinnati Museum Center and Book Review Editor CINCINNATI Kevin Ward The Filson Historical Society Matthew E. Stanley MUSEUM CENTER Donna Zaring are private non-profit organiza- Department of History BOARD OF TRUSTEES James M. Zimmerman and Political Science tions supported almost entirely Albany State University Chair FILSON HISTORICAL by gifts, grants, sponsorships, Edward D. Diller SOCIETY BOARD OF admission, and membership fees. Managing Editors DIRECTORS Jamie Evans Past Chair The Filson Historical Society Francie S. Hiltz President & CEO The Filson Historical Society Scott Gampfer Craig Buthod membership includes a subscrip- Cincinnati Museum Center Vice Chairs Greg D. Carmichael Chairman of the Board tion to OVH. Higher-level Cincin- Editorial Assistants Hon. Jeffrey P. Hopkins Carl M. Thomas nati Museum Center memberships Kayla Reddington Cynthia Walker Kenny also include an OVH subscription. The Filson Historical Society Rev. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Littsie of Cincinnati - Bibliography

Littsie of Cincinnati - Bibliography Angier, Bradford. How to Stay Alive in the Woods. London: Collier-MacMillian Ltd., 1962. "An Historical Review of the Children's Home of Cincinnati, Ohio, April 1, 1864 - December 31, 1865," Norman Paget, Dorothy Paget and Vincentia Woerman. (No publisher, no date of publication.) "Anne Sargent Bailey," Elizabeth Sheppard Hopely, Ohio Archaeological & Historical Quarterly, Volume 16, pgs. 340-347, 1907. Baldwin, Leland Dewitt. The Keelboat Ace on the Western Waters. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1941. Bates, Alan L. Western Rivers Cyclopedium. Leonia, New Jersey: Hustle Press, 1968. Brown, Kent L. (Ed). Medicine in Cleveland and Cuyohoga Counties. Cleveland: Academy of Medicine of Cleveland, 1977. Bryne, Bernard. "An Essay to Prove the Contagious Character of Malignant Cholera." Bolt, 1833. Causten, James. French Spoilation Claims. Baltimore: Baltimore Press by Robert Geddes, 1826. Chambers, John S. The Conquest of Cholera, America's Greatest Scourge. New York: The MacMillian Co., 1938. "Cholera in Cincinnati," Edwin Waterman Mitchell, Ohio State Medical Journal Historians Notebook, Volume 33, January 1937. Cincinnati Enquirer. July 4, 1839. Cincinnati Orphan Asylum - Annual Report of the Managers. (1834, 1835, 1838.) Cincinnati Historical Society. Cist, Charles. Cincinnati Directory 1834, 1836, 1840 and 1841. Coffin, Levi. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin. Cincinnati: R. Clarke & Co. 1880. Coleman, William H. Historical Sketch Book and Guide to New Orleans. New York: 1885. Columbia Baptist Church Records 1790-1910. Cincinnati, Ohio. Cincinnati Historical Society. Cramer, Zador, Spear, and Eichbaum. The Navigator. Pittsburgh: Robert Ferguson & Co., 1817. Dayton, Fred Erving. Steamboatin' Days. New York: Tudor Publishers, 1939. "Death By Cholera," September 24 - November 14. -

OTR Guidelines

HISTORIC CONSERVATION GUIDELINES FOR NEW CONSTRUCTION #THISISOTR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was developed through a Infill Committee Professional Volunteers: Over-the-Rhine Infill Design Competition: community effort led by the Over-the-Rhine Matt Deininger Sanyog Rathod, Sol Design + Consulting, 1st Place Foundation, the Over-the-Rhine Foundation’s Infill Nick Dewald Maren Kuspan, 2nd Place Committee, and professional consultants. Luke Field O'Sam Mardin, Professional Design Associates, Inc., Honorable Mention We wish to acknowledge the following: Shannon Hokanson Elizabeth Ickes Other Participants: Seth Maney Jim Guthrie, Hub + Weber Architects Over-the-Rhine Foundation Board of Trustees: Ana Ozaki Zoe Evans, Paige Michutka, and Alyssa Pack Darrick Dansby Adam Rayne Hermann Kamte, HKA | Hermann Kamte & Associates David Fatherree Anne Delano Steinert Eric Inglert, Eric Todd Inglert, AIA Tom Hadley Sean Suder Thomas Schroeder, ATA-Beilharz Marge Hammelrath Nancy Yerian Matt Ireton, K4 Architecture Reid Hartmann Consultation provided by the City of Cincinnati Office Paul Shirley, Pelican Studio Andy Holzhauser, Treasurer of the Urban Conservator: Ryan O'Malley, Platte Architecture + Design Beth Johnson, Urban Conservator Marilyn Hyland The competition was sponsored by: W. Kevin Pape, President Document design by: The Over-the-Rhine Foundation, Cincinnati Preservation Danny Klingler, Infill Committee Co-Chair Hyperquake Association, 3CDC, 8K Construction Company, Jennifer LeMasters Wirtz, Infill Committee Co-Chair the University of Cincinnati’s Niehoff Urban Studio, M+A Architects AIA Cincinnati, The Christian Moerlein Brewing Company, Seth Maney and An Anonymous Donor Special thanks to: Kristen M. Myers, Secretary Chris Heckman Sanyog Rathod Adam Hartke Frank Russell, Vice President Ann Senefeld This document was funded in part by: Sean Suder The Over-the-Rhine Foundation John Yung The Carol Ann and Ralph V. -

Rossford 2016 Reader

++++ history puts on a show ++++ PresentedP re s By RossfordRo + June 28-Julyy 2 ROSSFORDROSS VETERAN’S MEMORIAL PARK AND MARINANA MARIE CURIE JUNE 28 CHIEF CORNSTALK JUNE 29 MARY SHELLEY JUNE 30 DIAN FOSSEY JULY 1 THEODORE ROOSEVELT JULY 2 Performances begin at 7:30 p.m. Live music at 6:30 p.m. ++++++++++ ++++++++++ Brimfield Hamilton Gallipolis + + June 7-11 June 14-18 June 21-25 Photography: Janet Adams Photo Learn more at ohiohumanities.org Presented By Rossford 2016 Schedule of Events EVENING PERFORMANCES PROGRAMS & MUSIC +++++++ Daytime Programs for Youth — programs begin at 10:00 a.m. Live ON STAGE! Rossford Public Library, 720 Dixie Highway, Rossford Tuesday, June 28: Dan Cutler: Prehistoric People—How Primitive Were They? ROSSFORD VETERAN’S MEMORIAL PARK Wednesday, June 29: Susan Marie Frontczak: Once Upon a Time— AND MARINA Frankenstein 300 Hannum Avenue, Rossford Thursday, June 30: Dianne Moran: Animal Researchers Friday, July 1: Chuck Chalberg: Roosevelt as a Hunter & Explorer Performances begin at 7:30 p.m. Live local music at 6:30 p.m. Saturday, July 2: Susan Marie Frontczak: Storytelling: Science and Engineering through Stories Tuesday, June 28 Daytime Programs for Adults — programs begin at 2:00 p.m. Susan Marie Frontczak Rossford Public Library, 720 Dixie Highway, Rossford as Marie Curie Tuesday, June 28: Dan Cutler: How the “Skin Trade” Changed Traditional Native Values Wednesday, June 29: Susan Marie Frontczak: Does a Clone Have a Soul – Wednesday, June 29 or – Grappling with the Monster Dan Cutler Thursday, June 30: Dianne Moran: Dian Fossey, Passionate Mountain as Chief Cornstalk Gorilla Researcher and Defender Friday, July 1: Chuck Chalberg: Roosevelt’s Character and Roosevelt as an American Character Thursday, June 30 Saturday, July 2: Susan Marie Frontczak: Marie Curie—What Almost Susan Marie Frontczak Stopped Her as Mary Shelley Evening Music Schedule — Live local music begins at 6:30 p.m. -

Archaeological Investigations for the HAM-The Banks Street Grid Project, City of Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio PID # 77164/80629

Archaeological Investigations for the HAM-The Banks Street Grid Project, City of Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio PID # 77164/80629 G R AY & PA P E , I N C. ARCHAEOLOGY HISTORY HISTORIC PRESERVATION August 17, 2011 Lead Agency: Ohio Department of Transportation Prepared for: City of Cincinnati 801 Plum Street, Room 450 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Prepared by: Gray & Pape, Inc. 1318 Main Street Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Gray & Pape Project No. 10-0801.001 Project No. 10-0801.001 Archaeological Investigations for the HAM-The Banks Street Grid Project, City of Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio PID # 77164/80629 Lead Agency: Ohio Department of Transportation Prepared for: City of Cincinnati 801 Plum Street, Room 450 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Contact: Keith Pettit Tel: (513) 352-3224 Prepared by: Karen Niemel Garrard, Ph.D. Jennifer Mastri Burden, M.A. Gray & Pape, Inc. 1318 Main Street Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Tel: 513-287-7700 ____________________________ Karen Niemel Garrard, Ph.D. Senior Principal Investigator August 17, 2011 ABSTRACT Gray & Pape, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio, was contracted by the City of Cincinnati to conduct archaeological investigations for the HAM-The Banks Street Grid Project (PID 80629) in the City of Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio. The project will impact archaeological deposits associated with Site 33HA780, which is eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The archaeological work combined elements of a Phase II/III level of effort and was completed in accordance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended (36CFR800). The lead agency for this project is the Ohio Department of Transportation. -

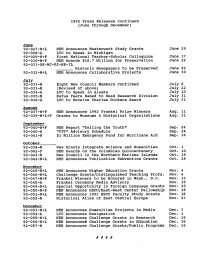

1992 Press Releases Continued (June Through December)

1992 Press Releases continued (June through December) June 92-027—N+L NEH Announces Masterwork Study Grants June 29 92-028-A LVC to Speak in Michigan 92-029-N+F First National Teacher-Scholar Colloquium June 17 92-030-N+F NEH Awards $18.7 Million for Preservation June 22 92-031-OK-NJ-RI-NE-IL _______ Historic Newspapers to be Preserved June 22 92-032-N+L NEH Announces Collaborative Projects June 30 July 92-033-N Eight New Council Members Confirmed July 6 92-033-R (Revised of above) July 22 92-034-A LVC to Speak in Alaska July 10 92-035-N Rufus Fears Named to Head Research Division July 31 92-036-A LVC to Receive Charles Dickens Award July 31 August 92-037-N+F NEH Announces 1992 Frankel Prize Winners Aug. 11 92-039-N+L+F Grants to Museums & Historical Organizations Aug. 31 S e p t e m b e r 92-040-N+F NEH Report "Telling the Truth" Sep. 24 92-040-A h t t t " Advisory Schedule Sep. 24 92-041-N $1 Million Emergency Fund for Hurricane Aid Sep. 16 October_______ 92-038-N New Grants Integrate Science and Humanities Oct. 1 92-042-F NEH Awards on the Columbian Quincentenary Oct. 10 92-043-N New Council in the Northern Mariana Islands Oct. 16 92-044-N+L NEH Announces Publication Subvention Grants Oct. 26 N o v e m b e r 92-045-N+L NEH Announces Higher Education Grants Nov. -

Standing Right Here: the Built Environment As a Tool for Historical Inquiry

Standing Right Here: The Built Environment as a Tool for Historical Inquiry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of History, College of Arts and Sciences by Anne Delano Steinert October 2020 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2015 M.S. Columbia University, 1995 B.A. Goucher College, 1992 Committee Chair: Tracy Teslow, PhD Abstract The built environment is an open archive—a twenty-four-hour museum of the past. The tangible, experiential nature of the urban built environment—streets, valleys, buildings, and bridges—helps historians uncover stories not always accessible in textual sources. The richness of the built environment gives historians opportunities to: invigorate their practice with new tools to uncover the stories of the past, expand the historical record with new understandings, and reach a wider audience with histories that feel relevant and meaningful to a broad range of citizens. This dissertation offers a sampling of material, methods and motivations historians can use to analyze the built environment as a source for their important work. Each of the five chapters of this dissertation uses the built environment to tell a previously unknown piece of Cincinnati’s urban history. The first chapter questions the inconvenient placement of the 1867 Roebling Suspension Bridge and uncovers the story of the ferry owner who recognized the bridge as a threat to his business. Chapter two explores privies, the outdoor toilets now missing from the built environment, and their use as sites for women to terminate pregnancies through abortion and infanticide. -

Introduction to Betty & Connie's OVER-THE-RHINE Tour Guide

Constance Lee Menefee and Betty Ann Smiddy 2008 [email protected] Introduction to betty & connie’s OVER-THE-RHINE tour guide Cincinnati was incorporated as a frontier town in 1802. Its growth into a thriving industrial city was assured when the first steamboat was launched on the Ohio River in 1812. It was the Ohio River, plus access to key resources for building and manufacturing like iron, coal, timber, limestone, and clay, that established Cincinnati as a major business center by the mid-1800’s. Industry thrived: Cincinnati became home to soap and glycerin works, cooperages, lumber yards, foundries, stone yards, tanneries, meat packing houses, silversmiths, tinners, cabinetmakers, machine makers, boot and shoe makers, printers, potters, and many breweries, peaking at 36 by 1860.1 The central business district became crowded with a variety of businesses willing to pay high rents for access to the river. Later arrivals were pushed north, into a basin area that had the Miami-Erie Canal – the “Rhine” – as a rough south and west boundary. This basin area became a significant port of entry for increasing numbers of eastern Europeans who were fleeing war, conscription, economic depression, and feudalistic land inheritance laws. As the German-speaking community grew, the area across the canal became known as “Over-the-Rhine.” The neighborhood was at once profoundly connected to the economic life of the city and separate in its strong European culture. Every block had businesses that provided the service and product necessities of life. To the Germans, that included churches, good food, and wholesome beer. A nickel beer bought a free buffet lunch. -

Cincinnati Streetcar: Phase I Cultural Resources Investigations

Project No. 10-6301.001 Cincinnati Streetcar: Phase I Cultural Resources Investigations Lead Agency: Federal Transit Administration Prepared for: Parsons Brinckerhoff 312 Elm Street, Suite 2500 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Contact: Jennifer Graf (513) 639-2145 Prepared by: Douglas Owen, M.A., Architectural Historian Gray & Pape, Inc. 1318 Main Street Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 (513) 287-7700 _____________________________ Patrick O’Bannon, Ph.D. Project Manager February 2011 ABSTRACT This report presents the results of a Phase I History/Architecture survey conducted by Gray & Pape, Inc., of Cincinnati, Ohio, on behalf of Parsons Brinckerhoff of Cincinnati, Ohio, for the proposed Cincinnati Streetcar project in Hamilton County, Ohio. The City of Cincinnati is sponsoring the development of a streetcar transit system to serve as an urban circulator for the downtown area and adjoining neighborhoods. The City has identified streetcar transit as a potential tool for improving local circulation, supporting sustainable community and economic development, and complementing other components of the local and regional transportation system. The project will be partially funded by federal grants, administered through the Federal Transit Administration, therefore requiring compliance with the Section 106 consultation process, as defined in 36 CFR 800. Gray & Pape defined an Area of Potential Effects (APE) for the undertaking that encompasses all parcels fronting the proposed streetcar routes. The APE is characterized by a dense, urban concentration of commercial and residential buildings located in Cincinnati’s Central Business District and the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. The literature review for this project entailed an examination of the Ohio Historic Preservation Office’s Online Mapping System and the City of Cincinnati’s CAGIS mapping system. -

Recent Scholarship in Quaker History

Recent Scholarship in Quaker History Compiled in December 2015 This document is available at the Friends Historical Association website: http://www.quakerhistory.org > Archives Abolition and Antislavery: a Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic / edited by Peter Hinks and John McKivigan. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, [2015]. Includes references to Quakers. Angell, Stephen W. “Quaker Lobbying on Behalf of the New START Treaty in 2010: A Window into the World of the Friends Committee on National Legislation,” in Stanley D. Brunn, ed., The Changing World Religion Map: Sacred Places, Identities, Practices, and Politics, chapter 185, 3541- 3558. New York: Springer, 2015. Barlow, Antony. He is Our Cousin, Cousin. York: Quacks Books, 2015. This is the author's study of his family origins which are principally rooted in the 17th century Quaker movement and which have flourished in many fields of endeavor over the past 350 years. Many examples are given of family members whose lives have impacted for the better the world in which we live. Whilst the names of Barlow, Nicholson, Neild, Cash, Bowly, Fry, Cadbury & Barber, are writ with greater prominence, there are many other families mentioned, who are of equal merit and distinction, and together make for a study that illustrates by example, the scope of their family connections. Barry, Heather E. "Naked Quakers Who Were Not so Naked: Seventeenth-Century Quaker Women in the Massachusetts Bay Colony", Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 43:2 (Summer 2015), 116-135. This article examines forty-five Quaker women who preached and protested against orthodox Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1656 to the 1670s.