Malice Necessary to Convict for Third-Degree Murder in Pennsylvania Still Requires Wickedness of Disposition and Hardness of Heart: Commonwealth V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ronald Cornish V. State of Maryland, No. 12, September Term, 2018

Ronald Cornish v. State of Maryland, No. 12, September Term, 2018. Opinion by Greene, J. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE – MARYLAND RULE 4-331 – NEWLY DISCOVERED EVIDENCE – PRIMA FACIE The Court of Appeals held that the facts alleged in Petitioner’s Motion for New Trial on the grounds of Newly Discovered Evidence established a prima facie basis for granting a new trial. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE – MARYLAND RULE 4-331 – NEWLY DISCOVERED EVIDENCE – RIGHT TO A HEARING The Court of Appeals held that the Circuit Court erred when it denied Petitioner a hearing on his Rule 4-331 Motion for New Trial based on Newly Discovered Evidence. Circuit Court for Baltimore City IN THE COURT OF APPEALS Case No. 115363026 Argued: September 12, 2018 OF MARYLAND No. 12 September Term, 2018 ______________________________________ RONALD CORNISH v. STATE OF MARYLAND Barbera, C.J. Greene, Adkins, McDonald, Watts, Hotten, Getty, JJ. ______________________________________ Opinion by Greene, J. ______________________________________ Filed: October 30, 2018 In this case, we consider under what circumstances a defendant has the right to a hearing upon filing a Maryland Rule 4-331(c) Motion for New Trial based on newly discovered evidence. More specifically, we must decide whether the trial judge was legally correct in denying Petitioner Ronald Cornish (“Mr. Cornish”) a hearing under the Rule. Petitioner was charged and convicted of first degree murder, use of a firearm in the commission of a crime of violence, and other related offenses. Thereafter, Mr. Cornish was sentenced to life imprisonment plus twenty years. Approximately two weeks after his sentencing, Mr. Cornish filed a Motion for a New Trial under Md. -

Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law

Nebraska Law Review Volume 76 | Issue 3 Article 2 1997 Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup John Rockwell Snowden University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation John Rockwell Snowden, Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup, 76 Neb. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol76/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. John Rockwell Snowden* Second Degree Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska: New Juice for an Old Cup TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 400 II. A Brief History of Murder and Malice ................. 401 A. Malice Emerges as a General Criminal Intent or Bad Attitude ...................................... 403 B. Malice Becomes Premeditation or Prior Planning... 404 C. Malice Matures as Particular States of Intention... 407 III. A History of Murder, Malice, and Manslaughter in Nebraska ............................................. 410 A. The Statutes ...................................... 410 B. The Cases ......................................... 418 IV. Puzzles of Nebraska Homicide Jurisprudence .......... 423 A. The Problem of State v. Dean: What is the Mens Rea for Second Degree Murder? ... 423 B. The Problem of State v. Jones: May an Intentional Homicide Be Manslaughter? ....................... 429 C. The Problem of State v. Cave: Must the State Prove Beyond a Reasonable Doubt that the Accused Did Not Act from an Adequate Provocation? . -

Murder - Proof of Malice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 7 (1966) Issue 2 Article 19 May 1966 Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965) Robert A. Hendel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Robert A. Hendel, Criminal Law - Murder - Proof of Malice. Biddle v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 14 (1965), 7 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 399 (1966), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol7/iss2/19 Copyright c 1966 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr 1966] CURRENT DECISIONS and is "powerless to stop drinking." " He is apparently under the same disability as the person who is forced to drink and since the involuntary drunk is excused from his actions, a logical analogy would leave the chronic alcoholic with the same defense. How- ever, the court refuses to either follow through, refute, or even men- tion the analogy and thus overlook the serious implication of the state- ments asserting that when the alcoholic drinks it is not his act. It is con- tent with the ruling that alcoholism and its recognized symptoms, specifically public drunkenness, cannot be punished. CharlesMcDonald Criminal Law-MuEDER-PROOF OF MALICE. In Biddle v. Common- 'wealtb,' the defendant was convicted of murder by starvation in the first degree of her infant, child and on appeal she claimed that the lower court erred in admitting her confession and that the evidence was not sufficient to sustain the first degree murder conviction. -

A Grinchy Crime Scene

A Grinchy Crime Scene Copyright 2017 DrM Elements of Criminal Law Under United States law, an element of a crime (or element of an offense) is one of a set of facts that must all be proven to convict a defendant of a crime. Before a court finds a defendant guilty of a criminal offense, the prosecution must present evidence that is credible and sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed each element of the particular crime charged. The component parts that make up any particular crime vary depending on the crime. The basic components of an offense are listed below. Generally, each element of an offense falls into one or another of these categories. At common law, conduct could not be considered criminal unless a defendant possessed some level of intention – either purpose, knowledge, or recklessness – with regard to both the nature of his alleged conduct and the existence of the factual circumstances under which the law considered that conduct criminal. The basic components include: 1. Mens rea refers to the crime's mental elements of the defendant's intent. This is a necessary element—that is, the criminal act must be voluntary or purposeful. Mens rea is the mental intention (mental fault), or the defendant's state of mind at the time of the offense. In general, guilt can be attributed to an individual who acts "purposely," "knowingly," "recklessly," or "negligently." 2. All crimes require actus reus. That is, a criminal act or an unlawful omission of an act, must have occurred. A person cannot be punished for thinking criminal thoughts. -

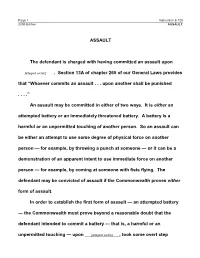

ASSAULT the Defendant Is Charged with Having Committed

Page 1 Instruction 6.120 2009 Edition ASSAULT ASSAULT The defendant is charged with having committed an assault upon [alleged victim] . Section 13A of chapter 265 of our General Laws provides that “Whoever commits an assault . upon another shall be punished . .” An assault may be committed in either of two ways. It is either an attempted battery or an immediately threatened battery. A battery is a harmful or an unpermitted touching of another person. So an assault can be either an attempt to use some degree of physical force on another person — for example, by throwing a punch at someone — or it can be a demonstration of an apparent intent to use immediate force on another person — for example, by coming at someone with fists flying. The defendant may be convicted of assault if the Commonwealth proves either form of assault. In order to establish the first form of assault — an attempted battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to commit a battery — that is, a harmful or an unpermitted touching — upon [alleged victim] , took some overt step Instruction 6.120 Page 2 ASSAULT 2009 Edition toward accomplishing that intent, and came reasonably close to doing so. With this form of assault, it is not necessary for the Commonwealth to show that [alleged victim] was put in fear or was even aware of the attempted battery. In order to prove the second form of assault — an imminently threatened battery — the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to put [alleged victim] in fear of an imminent battery, and engaged in some conduct toward [alleged victim] which [alleged victim] reasonably perceived as imminently threatening a battery. -

Malice in Tort

Washington University Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 January 1919 Malice in Tort William C. Eliot Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William C. Eliot, Malice in Tort, 4 ST. LOUIS L. REV. 050 (1919). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol4/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MALICE IN TORT As a general rule it may be stated that malice is of no conse- quence in an action of tort other than to increase the amount of damages,if a cause of action is found and that whatever is not otherwise actionable will not be rendered so by a malicious motive. In the case of Allen v. Flood, which is perhaps the leading one on the subject, the plaintiffs were shipwrights who did either iron or wooden work as the job demanded. They were put on the same piece of work with the members of a union, which objected to shipwrights doing both kinds of work. When the iron men found that the plaintiffs also did wooden work they called in Allen, a delegate of their union, and informed him of their intention to stop work unless the plaintiffs were discharged. As a result of Allen's conference with the employers plaintiffs were discharged. -

Criminal Assault Includes Both a Specific Intent to Commit a Battery, and a Battery That Is Otherwise Unprivileged Committed with Only General Intent

QUESTION 5 Don has owned Don's Market in the central city for twelve years. He has been robbed and burglarized ten times in the past ten months. The police have never arrested anyone. At a neighborhood crime prevention meeting, apolice officer told Don of the state's new "shoot the burglar" law. That law reads: Any citizen may defend his or her place of residence against intrusion by a burglar, or other felon, by the use of deadly force. Don moved a cot and a hot plate into the back of the Market and began sleeping there, with a shotgun at the ready. After several weeks of waiting, one night Don heard noises. When he went to the door, he saw several young men running away. It then dawned on him that, even with the shotgun, he might be in a precarious position. He would likely only get one shot and any burglars would get the next ones. With this in mind, he loaded the shotgun and fastened it to the counter, facing the front door. He attached a string to the trigger so that the gun would fire when the door was opened. Next, thinking that when burglars enter it would be better if they damaged as little as possible, he unlocked the front door. He then went out the back window and down the block to sleep at his girlfriend's, where he had been staying for most of the past year. That same night a police officer, making his rounds, tried the door of the Market, found it open, poked his head in, and was severely wounded by the blast. -

Caselaw Update: Week Ending April 24, 2015 17-15 Possibility of Parole.” the Trial Court Denied Prolongation, Even a Short One, Is Unreasonable, Felony Murder

Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia UPDATE WEEK ENDING APRIL 24, 2015 State Prosecution Support Staff THIS WEEK: • Financial Transaction Card Fraud the car wash transaction was not introduced Charles A. Spahos Executive Director • Void Sentences; Aggravating into evidence at trial. The investigating officer Circumstances testified the card used there was the “card that Todd Ashley • Search & Seizure; Prolonged Stop was reported stolen,” but the evidence showed Deputy Director that the victim had several credit cards stolen • Sentencing; Mutual Combat from her wallet, and the officer could not recall Chuck Olson General Counsel the name of the card used at the car wash, which he said was written in a case file he Lalaine Briones had left at his office. Accordingly, appellant’s State Prosecution Support Director Financial Transaction Card conviction for financial transaction card fraud Fraud as alleged in Count 2 of the indictment was Sharla Jackson Streeter v. State, A14A1981 (3/19/15) reversed. Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Crimes Against Children Resource Prosecutor Appellant was convicted of burglary, two Void Sentences; Aggravat- counts of financial transaction card fraud, ing Circumstances Todd Hayes three counts of financial transaction card theft, Cordova v. State, S15A0110 (4/20/15) Sr. Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor and one count of attempt to commit financial Appellant appealed from the denial of his Joseph L. Stone transaction card fraud. The evidence showed Traffic Safety Resource Prosecutor that she entered a corporate office building, motion to vacate void sentences. The record went into the victim’s office and stole a wallet showed that in 1997, he was indicted for malice Gary Bergman from the victim’s purse. -

Tort of Misfeasance in Public Office

MISFEASANCE IN PUBLIC OFFICE by Mark Aronson1 INTRODUCTION The fact that administrative or executive action is invalid according to public law principles is an insufficient basis for claiming common law damages. The remedies in public law for invalid government action are orders that quash the underlying decision, or prohibit its further enforcement, or declare it to be null and void. Unlawful failure or refusal to perform a public duty is addressed by a mandatory order to perform the duty according to law. In other words, harm caused by invalid government action or inaction is not compensable2 at common law just because it was invalid. The tort of misfeasance in public office represents a “safety net” adjustment to that position, by allowing damages where the public defendant’s unlawfulness is grossly culpable at a moral level. Briefly, misfeasance in public office is a tort remedy for harm caused by acts or omissions that amounted to: 1. an abuse of public power or authority; 2. by a public officer; 3. who either a. knew that he or she was abusing their public power or authority, or b. was recklessly indifferent as to the limits to or restraints upon their public power or authority; 4. and who acted or omitted to act a. with either the intention of harming the claimant (so-called “targeted malice”), or b. with the knowledge of the probability of harming the claimant, or c. with a conscious and reckless indifference to the probability of harming the claimant. In short, misfeasance is an intentional tort, where the relevant intention is bad faith. -

The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law

This article was originally published as: Amanda M. Rose The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law 43 The Journal of Corporation Law 77 (2017) +(,121/,1( Citation: Amanda M. Rose, The Reasonable Investor of Federal Securities Law: Insights from Tort Law's Reasonable Person & Suggested Reforms, 43 J. Corp. L. 77 (2017) Provided by: Vanderbilt University Law School Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue Apr 3 17:02:15 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device The "Reasonable Investor" of Federal Securities Law: Insights from Tort Law's "Reasonable Person" & Suggested Reforms Amanda M. Rose* Federalsecurities law defines the materiality ofcorporatedisclosures by reference to the views of a hypothetical "reasonableinvestor. " For decades the reasonable investor standardhas been aflashpointfor debate-with critics complaining of the uncertainty it generates and defenders warning of the under-inclusiveness of bright-line alternatives. This Article attempts to shed fresh light on the issue by considering how the reasonable investor differs from its common law antecedent, the reasonableperson of tort law. The differences identified suggest that the reasonableinvestor standardis more costly than tort, law's reasonableperson standard-theuncertainty it generates is both greater and more pernicious. But the analysis also reveals promising ways to mitigate these costs while retainingthe benefits of theflexible standard 1. -

Defamation Law - the Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc

Volume 17 Issue 2 Summer 1987 Summer 1987 Defamation Law - The Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps Debra A. Hill Recommended Citation Debra A. Hill, Defamation Law - The Private Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps, 17 N.M. L. Rev. 363 (1987). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol17/iss2/8 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr DEFAMATION LAW-The Private Figure Plaintiff Must Establish a New Element to Make a Prima Facie Showing: Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps I. INTRODUCTION The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps' imposes a new element of proof on private figure plaintiffs2 in media defamation actions.' In Hepps, the Supreme Court held that where a newspaper publishes speech about matters of public interest, the plaintiff now bears the burden of showing that the defamatory statements4 are false.5 This decision abrogates the common law rule that the defendant bears the burden of proving the truth of the defamatory statements.' This Note first discusses the historical background of distinctions enun- ciated by the Court in making decisions in defamation cases: the status of the plaintiff, the contents of the defamatory speech, and the status of the defendant. The Note then reviews the U.S. -

Guide to Ny Evidence Article 3 Presumptions & Prima Facie Evidence

GUIDE TO NY EVIDENCE ARTICLE 3 PRESUMPTIONS & PRIMA FACIE EVIDENCE Table of Contents Presumptions 3.01 Presumptions in Civil Proceedings 3.03 Presumptions in Criminal Proceedings Accorded People 3.05 Presumptions in Criminal Proceedings Accorded Defendant Prima Facie Evidence 3.07 Certificates of Judgments of Conviction & Fingerprints (CPL 60.60) 3.10 Inspection Certificate of US Dept of Agriculture (CPLR 4529) 3.12 Ancient Filed Maps, Surveys & Real Property Records (CPLR 4522) 3.14 Conveyance of Real Property Without the State (CPLR 4524) 3.16 Death or Other Status of a Missing Person (CPLR 4527) 3.18 Marriage Certificate (CPLR 4526; DRL 14-A) 3.20 Affidavit of Service or Posting Notice by Person Unavailable at Trial (CPLR 4531) 3.22 Standard of Measurement Used by Surveyor (CPLR 4534) 3.24 Search by Title Insurance or Abstract Company (CPLR 4523) 3.26 Copies of Statements Under UCC Article 9 (CPLR 4525) 3.28 Weather Conditions (CPLR 4528) 3.01. Presumptions in Civil Proceedings (1) This rule applies in civil proceedings to a “presumption,” which as provided in subdivisions two and three is rebuttable; it does not apply to a “conclusive” presumption, that is, a “presumption” not subject to rebuttal, or to an “inference” which permits, but does not require, the trier of fact to draw a conclusion from a proven fact. (2) A presumption is created by statute or decisional law, and requires that if one fact (the “basic fact”) is established, the trier of fact must find that another fact (the “presumed fact”) is thereby established unless rebutted as provided in subdivision three.