The First Beautiful Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapid Sensory Profiling of Tennis Rackets †

Proceedings Rapid Sensory Profiling of Tennis Rackets † Maximilian Bauer 1,*, Sean Mitchell 1, Nathan Elliott 2 and Jonathan Roberts 1 1 Wolfson School of Mechanical, Electrical and Manufacturing Engineering, Loughborough University, Loughborough LE11 3QF, UK; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (J.R.) 2 R&D Racquet Sports, HEAD Sport GmbH, 6921 Kennelbach, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-7902-592-659 † Presented at the 13th Conference of the International Sports Engineering Association, Online, 22–26 June 2020. Published: 15 June 2020 Abstract: Tennis racket manufacturers rely on subjective assessments from testers during the development process. However, these assessments often lack validity and include multiple sources of inconsistency in the way testers make subjective ratings. The purpose of this research was to investigate the suitability of the free-choice profiling (FCP) method in combination with principle component analysis (PCA) and multiple factor analysis (MFA) to determine the sensory profile of rackets. FCP was found to be a suitable technique to quickly evaluate the sensory profile of rackets; however, consumer testers tended to use ill-defined, industry-generated terms, which negatively impacted discrimination and inter-rater agreement. Discrimination and inter-rater agreement improved for attributes referring to measurable parameters of the rackets, such as vibration. This study furthers our understanding of tennis racket feel and supports racket engineers in designing new subjective testing methods, which provide more meaningful data regarding racket feel. Keywords: feel; sensory analysis; tennis rackets; free-choice profiling; PCA; MFA 1. Introduction Since performance advancements have become more challenging in the tennis racket industry, manufacturers rely increasingly on consumer feedback in terms of racket feel to provide direction in the development process. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 4 | JanUaRy - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE CHANGING STATUS OF LAWN TENIS Dr. Ganesh Narayanrao Kadam Asst. Prof. College Of Agriculture Naigaon Bz. Dist. Nanded. ABSTRACT : Tennis is a racket sport that can be played independently against a solitary adversary (singles) or between two groups of two players each (copies). Every player utilizes a tennis racket that is hung with rope to strike an empty elastic ball secured with felt over or around a net and into the rival's court. The object of the diversion is to move the ball so that the rival can't play a legitimate return. The player who can't restore the ball won't pick up a point, while the contrary player will. KEYWORDS : solitary adversary , dimensions of society , Tennis. INTRODUCTION Tennis is an Olympic game and is played at all dimensions of society and at all ages. The game can be played by any individual who can hold a racket, including wheelchair clients. The advanced round of tennis started in Birmingham, England, in the late nineteenth century as grass tennis.[1] It had close associations both to different field (garden) amusements, for example, croquet and bowls just as to the more established racket sport today called genuine tennis. Amid the majority of the nineteenth century, actually, the term tennis alluded to genuine tennis, not grass tennis: for instance, in Disraeli's epic Sybil (1845), Lord Eugene De Vere reports that he will "go down to Hampton Court and play tennis. -

Les Jeux De Paume : Systèmes Des Scores, Morphismes Et Paradoxes Mathématiques Et Sciences Humaines, Tome 92 (1985), P

MATHÉMATIQUES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES PIERRE PARLEBAS Les jeux de paume : systèmes des scores, morphismes et paradoxes Mathématiques et sciences humaines, tome 92 (1985), p. 41-68 <http://www.numdam.org/item?id=MSH_1985__92__41_0> © Centre d’analyse et de mathématiques sociales de l’EHESS, 1985, tous droits réservés. L’accès aux archives de la revue « Mathématiques et sciences humaines » (http:// msh.revues.org/) implique l’accord avec les conditions générales d’utilisation (http://www. numdam.org/conditions). Toute utilisation commerciale ou impression systématique est consti- tutive d’une infraction pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit conte- nir la présente mention de copyright. Article numérisé dans le cadre du programme Numérisation de documents anciens mathématiques http://www.numdam.org/ 41 LES JEUX DE PAUME : SYSTEMES DES SCORES, MORPHISMES ET PARADOXES Pierre PARLEBAS* "Car vous savez que ce noble jeu a toujours fait le divertissement des per- sonnes de la première qualité et bientôt vous verrez que s’il est utile pour l’exercice du corps, il est très capable et très digne aussi de fixer les mé- ditations de l’esprit". C’est en ces termes insolites que Jacques Bernoulli introduit sa Lettre à un Amy, sur les Parties du Jeu de Paume ([1] p.2) , lettre qui clôt le célèbre Ars conjectandi, ouvrage posthume publié en 1713, dans lequel l’auteur jette les fondements d’une science de la décision. Pas plus que Pascal, Bernoulli n’hésite à choisir ses exemples dans l’univers des jeux. "J’entre dans le détail de toutes les particularités de mon sujet". -

Tennis Court Conversion to Decoturf

July 28, 2017 Dear Members: Starting in early August, we have decided to change the surface of clay tennis courts 8-11 to DecoTurf Tennis Surface. We make this change only after much deliberation and discussion both internally, with industry experts, and with members. We realize that some of you enjoy the clay courts; however, the DecoTurf courts we are installing should be a great compromise between having a softer surface and a court that provides a consistent bounce and playing surface appealing to all members. The evolution of changing clay to hard courts at the Club began in 2001 when 5 courts (3 indoor clay and 2 bubbled clay) were converted from clay to hard courts. We have found overall that the demand for a consistent playing surface is overwhelmingly requested as compared to clay courts. With each passing year, we have seen the demand and request for clay courts decrease as compared to hard courts. After much consultation, we chose DecoTurf as the surface we would use for a number of reasons. Mainly, it provides a rubberized layer of material beneath the painted surface in order to be easier on a player’s body. There are a few local clubs that have converted to “softer” surfaces over the past few years. Without detailing each one specifically, most of them do not apply all of the coats required to be truly softer. The reason is simple, the more coats you add, the more the system costs! We have contracted to apply the maximum recommended amount of coats to achieve the softest surface possible using this system. -

Top 25 US Amateur Court Tennis Players

2005-2006 Annual Report Table of Contents President’s Report ..................................................................2-3 USCTA 50th Anniversary ...........................................................4-5 Board of Governors ....................................................................6-9 Financial Report 2005-2006 ..................................................... 10-11 Treasurer’s Report ........................................................................... 12 History of the USCTA ........................................................................ 13 USCTA Bylaws ................................................................................. 14-15 U.S. Court Tennis Preservation Foundation ..................................... 16-17 Feature: USCTA 50-Year Timeline ..................................................... 18-21 Tournament Play Guidelines ................................................................. 22 Top 25 U.S. Amateurs ............................................................................ 22 Club Reports .................................................................................... 23-36 Tournament Draws .......................................................................... 37-50 Record of Champions ...................................................................... 51-58 International Clubs and Associations ............................................. 59-62 International Court Tennis Hall of Fame............................................ 62 Membership Information -

Physics of Tennis Lesson 4 Energy

The Physics of Tennis Lesson 4: Energy changes when a ball interacts with different surfaces Unit Overview: In this unit students continue to develop understanding of what can be at first glance a complicated system, the game of tennis. In this activity we have taken two components of the game of tennis, the ball and court, to see if we can model the interactions between them. This activity focuses on the energy interactions between ball and court. Objectives: Students will be able to- • Describe what forces interact when the ball hits a surface. • Understand what changes occur when potential and kinetic energy conversion is taking place within a system. At the high school level students should include connections to the concept of “work =FxD” and calculations of Ek = ½ 2 mv and Ep =mgh according to the conservation of energy principal. • Identify the types of energy used in this system. (restricted to potential & kinetic energy) • Comparative relative energy losses for typical court compositions. Lesson Time Required: Four class periods Next Generation Science/Common Core Standards: • NGSS: HS-PS3-1.Create a computational model to calculate the change in the energy of one component in a system when the change in energy of the other component(s) and energy flows in and out of the system are known. • CCSS.Math. Content: 8.F.B.4 Use functions to model relationships between quantities. • Construct a function to model a linear relationship between two quantities. Determine the rate of change and initial value of the function from a description of a relationship or from two (x, y) values, including reading these from a table or from a graph. -

The Tennis Court

M. ROSS ARCH. 422 • A RACQUET CLUB FOR LUBBOCK, TEXAS. A Racquet Club for Lubbock, Texas A Thesis Program in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Bachelor of Architecture degree. Design Option Presented by Michael David Ross Texas Tech University Spring 1978 1, INTRODUCTION 2, THE CLIENT 3, FINANCING 4, THE SITE 11 S> FACILITIES 24 ^, RESTRICTIONS 40 7, APPENDIX 54 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE NATURE AND SCOPE OF THE PROJECT The nature of this thesis program is the development of the most precise and complete collection of data concerning my topic, A Racquet Club for Lubbock, Texas. Some of the questions this program will answer are: What is a Racquet Club? Who this Racquet Club is for? Where is this Racquet Club located? What goes on in this club? The elements composing the physical make-up of the facility are: 1. Clubhouse A) offices B) lounge and dining C) pro-shop D) lockers and dressing facilities E) indoor tennis and racquet ball courts 2. Outdoor tennis courts This facility not only will enhance the city of Lubbock but also provide its members a com plex that enables them to play the game as it should be played and to savor the deepest pleas ure the game has to offer. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT The name and the game came from the ancient net and racquet sport known in France where it was invented, as Jeu de Paume. This sport had its origins in the Middle Ages. It is mentioned in twelfth and thirteenth century manuscripts. In the sixteenth century the game was known to be exclusively an aristo cratic game because of the high cost of building courts. -

A People's History of Tennis

A People’s History of Tennis ‘Great news – playing tennis is not inconsistent with radical politics. This is just one of the fascinating facts in this amazing history of our sport.’ – Lord Richard Layard, Emeritus Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics and co-author of Thrive: The Power of Psychological Therapy ‘This antidote to cream teas and privilege celebrates tennis and its enthusiasts through the sport’s hitherto silenced stories. A great read.’ – Kath Woodward, Professor of Sociology, Open University and author of Social Sciences: The Big Issues ‘We might think of lawn tennis as a sport of the privileged, but this fascinating, beautifully written book reveals that in its 150-year history it has been played with passion by women, lesbians and gays, ethnic minorities and socialists alike.’ – Lucy Bland, Professor of Social and Cultural History, Anglia Ruskin University and author of Britain’s ‘Brown Babies’: The Stories of Children Born to Black GIs and British Women in the Second World War ‘David Berry’s delightfully gossipy book delves into the personal histories of tennis players famous and unknown. He lovingly charts the progress of the game since its beginnings in the Victorian period and explains why so many people, players and spectators, love it.’ – Elizabeth Wilson, author of Love Game: A History of Tennis, From Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon ‘A suffragette plot to burn down Wimbledon, Jewish quotas at your local tennis club, All England Married Couples Championships – you think you know tennis and then along comes this compelling little gem by David Berry, positing a progressive social history of the sport that surprises and delights. -

Squash Program

Youth Squash Program What is Squash? According to an article published in Men’s Fitness Magazine: You'll need a racquet, an opponent, a ball, and an enclosed court—most colleges and large gyms have them. Alternate hitting the ball off the front wall until someone loses the point. This happens when you allow the ball to bounce twice, or when you whack it out of bounds—below the 19-inch strip of metal (the "tin") along the bottom of the front wall, or above the red line around the top of the court. First one to 11 points wins the game; best of three or five wins the match. It may sound simple, but Squash is a challenging and rewarding game. And no one in South Jersey does it better than Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness. Why should you choose Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness Squash program? Greate Bay Racquet and Fitness is South Jersey's premiere racquet sports facility. Our full-service Squash club features: Four Squash courts o Two International Singles Courts o Two North American Doubles Courts Coaching from our full-time Squash professional Access to our Squash pro shop Lessons and clinics A track-record of successful juniors programs The best amenities for proper training; Locker rooms, Steam Room, Sauna 1 Youth Squash Program Greg Park – Squash Professional Greg Park is the Head Squash Professional at Greate Bay Racquet & Fitness Club. He is a Touring Squash Professional who is currently ranked 10th in the World and 2nd in the United States by the SDA Pro Tour. -

Stories from the Archives

STORIES FROM THE ARCHIVES: The enduring popularity of tennis The popular sport of tennis descends from a game called “real tennis” or “royal tennis” that probably began in France in the 12th century. It was known as jeu de paume (game of the palm) because the ball was struck with the palm of the hand. Racquets were introduced in the 16th century. Lawn tennis, what we know today as tennis, began in Birmingham, England in the early 1860s. The first Lawn Tennis Championship was held at Wimbledon in 1877. The popularity of the game arrived in Australia in 1875 when a “real tennis” club was established in Hobart. Five years later Australia’s first tennis tournament was held at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. We can read of a tennis club at PLC Sydney in the first issue of the Aurora Australis, published in December 1893. Tennis court at PLC, 1894 “B” Tennis Team, 1913 Tildesley Shield The Tildesley Tennis Shield competition was first held in 1918. It is named after Miss Evelyn Mary Tildesley, who was then the Headmistress of Normanhurst School, in Ashfield. She donated a beautiful oak and bronze shield that was to be awarded to the winning independent girls’ school. It is the most coveted trophy in school tennis because it teaches the girls to play for their school rather than for themselves, its special value lying in the fact that at least 12 girls, with a maximum of 32, according to the number of pupils over 12 years of age, compete for the trophy, thereby giving a 1 number of the younger girls an opportunity of representing their school which they would not otherwise get until much later. -

Tennis Courts: a Construction and Maintenance Manual

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 677 EF 005 376 TITLE Tennis Courts: A Construction and Maintenance Manual. INSTITUTION United States Tennis Court & Track Builders Association.; United States Tennis Association. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 246p.; Colored photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM U.S. Tennis Court & Track Builders Association, 3525 Ellicott Mills Dr., Suite N., Ellicott City, MD 21043-4547. Tel: 410-418-4800; Fax: 410-418-4805; Web site: <http://www.ustctba.com>. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) -- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Construction (Process); *Facility Guidelines; Facility Improvement; Facility Planning; *Maintenance; *Tennis IDENTIFIERS *Athletic Facilities ABSTRACT This manual addresses court design and planning; the construction process; court surface selection; accessories and amenities; indoor tennis court design and renovation; care and maintenance tips; and court repair, reconstruction, and renovation. General and membership information is provided on the U.S. Tennis Court and Track Builders Association and the U.S. Tennis Association, along with lists of certified tennis court builders and award winning tennis courts from past years. Numerous design and layout drawings are also included, along with Tennis Industry Magazine's maintenance planner. Sources of information and a glossary of terms conclude the manual. (GR) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made -

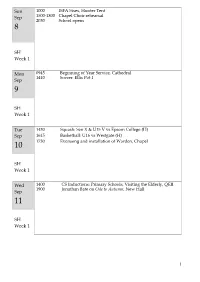

Sun Sep SH Week 1 Mon Sep SH Week 1 Tue

Sun 1000 ISFA Sixes, Hunter Tent Sep 1500-1800 Chapel Choir rehearsal 2030 School opens 8 SH Week 1 Mon 0945 Beginning of Year Service, Cathedral 1410 Soccer: Ellis Pot I Sep 9 SH Week 1 Tue 1430 Squash: Sen X & U15 V vs Epsom College (H) Sep 1615 Basketball: U16 vs Westgate (H) 1730 Evensong and installation of Warden, Chapel 10 SH Week 1 Wed 1400 CS Inductions: Primary Schools, Visiting the Elderly, QEII 1900 Jonathan Bate on Ode to Autumn, New Hall Sep 11 SH Week 1 1 0845 Road Safety Presentation, New Hall (JP only) Thur 1400 Golf: U18 & U16 vs Marlborough College (H) Sep 1415 Fencing vs Bradfield (A) dep 1305 1430 Squash: Sen III & U16 III vs Marlborough & Cheltenham (A) 12 dep 1305 1530 Soccer: YA, YC vs Twyford School (H) 1630 Soccer: Soccer XI vs Abingdon (A), dep 1430 1730 Eucharist, Chapel SH 1830 Friends Pre-lecture Drinks Week 1 1900 Friends Lecture: Re-viewing Winchester College by the Headmaster, New Hall (Friends only) 1410 Soccer: Flower Pot I Fri Sep 13 SH Week 1 All Day Rowing: JP & MP only at Isis Sculls (A) dep 0700, rtn 2000 Sat All Day Sailing: 1st vs Sir Reginald Bennett Cup (vs. OWs, Radley, ORs) Sep (A) dep 1600, rtn Sun 1930 14 0900-1300 Sixth Form 2020 Open Day, School 1130 Goddard Day Service, Chapel TW 1230 Goddard Day Reception followed by Lunch, New Hall 1430 Soccer: 1st XI, 2nd XI, 3rd XI, 4th XI, 5th XI, 6th XI, JCA, JCB, SH JCC, JCD, JCE vs Eton (A) dep 1230 Week 1 1430 Soccer: SCA, SCB, SCC, SCD, YA, YB, YC, YD, YE vs Eton (H) 1700-1800 Glee Club rehearsal, Music School Hall: Bernstein Chichester Psalms,