The Case of Danica Patrick in NASCAR a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NASCAR Sponsorship: Who Is the Real Winner? an Event Study Proposal

NASCAR Sponsorship: Who is the Real Winner? An event study proposal A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Meredith Seurkamp May 2006 Oxford, Ohio ii ABSTRACT NASCAR Sponsorship: Who is the Real Winner? An event study proposal by Meredith Seurkamp This paper investigates the costs and benefits of NASCAR sponsorship. Sports sponsorship is increasing in popularity as marketers attempt to build more personal relationships with their consumers. These sponsorships range from athlete endorsements to the sponsorship of an event or physical venue. These types of sponsorships have a number of costs and benefits, as reviewed in this paper, and the individual firm must use its discretion whether sports sponsorship coincides with its marketing goals. NASCAR, a sport that has experienced a recent boom in popularity, is one of the most lucrative sponsorship venues in professional sports. NASCAR, which began as a single race in 1936, now claims seventy-five million fans and over one hundred FORTUNE 500 companies as sponsors. NASCAR offers a wide variety of sponsorship opportunities, such as driver sponsorship, event sponsorship, track signage, and a number of other options. This paper investigates the fan base at which these marketing messages are directed. Research of NASCAR fans indicates that these fans are typically more brand loyal than the average consumer. NASCAR fans exhibit particular loyalty to NASCAR sponsors that financially support the auto racing sport. The paper further explains who composes the NASCAR fan base and how NASCAR looks to expand into additional markets. -

KEVIN HARVICK: Track Performance History

KEVIN HARVICK: Track Performance History ATLANTA MOTOR SPEEDWAY (1.54-mile oval) Year Event Start Finish Status/Laps Laps Led Earnings 2019 Folds of Honor 500 18 4 Running, 325/325 45 N/A 2018 Folds of Honor 500 3 1 Running, 325/325 181 N/A 2017 Folds of Honor 500 1 9 Running, 325/325 292 N/A 2016 Folds of Honor 500 6 6 Running, 330/330 131 N/A 2015 Folds of Honor 500 2 2 Running, 325/325 116 $284,080 2014 Oral-B USA 500 1 19 Running, 325/325 195 $158,218 2013 AdvoCare 500 30 9 Running, 325/325 0 $162,126 2012 ×AdvoCare 500 24 5 Running, 327/327 101 $172,101 2011 AdvoCare 500 21 7 Running, 325/325 0 $159,361 2010 ×Kobalt Tools 500 35 9 Running, 341/341 0 $127,776 Emory Healthcare 500 29 33 Vibration, 309/325 0 $121,026 2009 ×Kobalt Tools 500 10 4 Running, 330/330 0 $143,728 Pep Boys Auto 500 18 2 Running, 325/325 66 $248,328 2008 Kobalt Tools 500 8 7 Running, 325/325 0 $124,086 Pep Boys Auto 500 6 13 Running, 325/325 0 $144,461 2007 Atlanta 500 36 25 Running, 324/325 1 $117,736 ×Pep Boys Auto 500 34 15 Running, 329/329 1 $140,961 2006 Golden Corral 500 6 39 Running, 313/325 0 $102,876 †Bass Pro Shops 500 2 31 Running, 321/325 9 $123,536 2005 Golden Corral 500 36 21 Running, 324/325 0 $106,826 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 31 22 Running, 323/325 0 $129,186 2004 Golden Corral 500 8 32 Running, 318/325 0 $90,963 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 9 35 Engine, 296/325 0 $101,478 2003 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 I 17 19 Running, 323/325 0 $87,968 Bass Pro Shops/MBNA 500 II 10 20 Running, 324/325 41 $110,753 2002 MBNA America 500 8 39 Running, 254/325 0 $85,218 -

MOTORSPORTS a North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat

MOTORSPORTS A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat A REPORT PREPARED FOR NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS ASSOCIATION BY IN COOPERATION WITH FUNDED BY: RURAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTER, THE GOLDEN LEAF FOUNDATION AND NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS FOUNDATION October 2004 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remarks 6 Introduction 7 Methodology 8 Impact of Industry 9 History of Motorsports in North Carolina 10 Best Practices / Competitive Threats 14 Overview of Best Practices 15 Virginia Motorsports Initiative 16 South Carolina Initiative 18 Findings 20 Overview of Findings 21 Motorsports Cluster 23 NASCAR Realignment and Its Consequences 25 Events 25 Teams 27 Drivers 31 NASCAR Venues 31 NASCAR All-Star Race 32 Suppliers 32 Technology and Educational Institutions 35 A Strong Foothold in Motorsports Technology 35 Needed Enhancements in Technology Resources 37 North Carolina Motorsports Testing and Research Complex 38 The Sanford Holshouser Business Development Group and UNC Charlotte Urban Institute 2 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat Next Steps on Motorsports Task Force 40 Venues 41 Sanctioning Bodies/Events 43 Drag Racing 44 Museums 46 Television, Film and Radio Production 49 Marketing and Public Relations Firms 51 Philanthropic Activities 53 Local Travel and Tourism Professionals 55 Local Business Recruitment Professionals 57 Input From State Economic Development Officials 61 Recommendations - State Policies and Programs 63 Governor/Commerce Secretary 65 North -

Jamestown Classic Car Club “RUMBLER”

RUMBLER 40 CLASSIC CAR 18 MINISTRY SUMMARY Scott W. Block 1966 Chevrolet Impala In the RUMBLER Words SS 427 20 1969 CHEVROLET RUMBLER 42 CALENDAR OF 1 CAMARO ZL1 COPO CONTENTS EVENTS 9560 1 CLUB MEETING 45 SWAP SHOP 21 HISTORIC RACE Time & Place 48 CAR CLUB SITES TRACKS 2 BISON 6 50 DAKOTA Bandimere Speedway Show Times BLACKTOP TOUR LOOKING "Thunder Mountain" 2 HAGERTY 52 MEMBERSHIP TOWARDS 22 THE FUTURE INSURANCE APPLICATION CO-FOUNDER DEAD Club President "Skovy" 23 MUSCLE CAR HERO 3 BIRTHDAYS The (FORCE) behind April John Force's Daughters 3 ACTIVE MEMBERS 23 Ashley Force 4 BUFFALO CITY 26 Brittany Force TOURISM 29 Courtney Force Searle Swedlund HOT ROD 31 JAMESTOWN 5 MAGAZINE CLASSIC CAR CLUB Drives the 2014 Z28 32 AROUND MILL HILL 1969 PONTIAC Chieftain Conference 12 JUDGE Center HINT OF THE MONTH Found in a Barn 33 JAMESTOWN ELKS “Scenic Overlook” 13 CHRYSLER TO 34 CLASSIC CAR SCHOOLS SUMMARY Crush Vipers 1931 Lincoln Model K 14 RUMBLER TECH SCAVENGER HUNT 37 CLASSIC CAR How to put a Classic “Red Pants (Same Pair SUMMARY Muncie behind your LS 1947 Chevy Aerosedan with 1 long leg & 1 short Swap leg)” P a g e | 2 was a cool feeling how the area loves their hot rods. Seen the “Count” and Kevin and that were pretty cool also. Our car show is set for September 20th at Don Wilhelm Inc. here in Jamestown. Last year we had 96 cars, trucks, and bikes show up. Impressive to say the least. Can we crack the century mark this year? We’ll see. -

500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More!

BOOMER Indy For the best years of your life NEW! BOOMER+ Section Pull-Out for Boomers their helping parents 500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More! Women of the 500 Helping Hands of Freedom Free Summer Concerts MAY / JUNE 2016 IndyBoomer.com There’s more to Unique Home Solutions than just Windows and Doors! Watch for Unique Home Safety on Boomer TV Sundays at 10:30am WISH-TV Ch. 8 • 50% of ALL accidents happen in the home • $40,000+ is average cost of Assisted Living • 1 in every 3 seniors fall each year HANDYMAN TEAM: For all of those little odd jobs on your “Honey Do” list such as installation of pull down staircases, repair screens, clean decks, hang mirrors and pictures, etc. HOME SAFETY DIVISION: Certified Aging in Place Specialists (CAPS) and employee install crews offer quality products and 30+ years of A+ rated customer service. A variety of safe and decorative options are available to help prevent falls and help you stay in your home longer! Local Office Walk-in tubs and tub-to-shower conversions Slip resistant flooring Multi-functional accessory grab bars Higher-rise toilets Ramps/railings Lever faucets/lever door handles A free visit will help you discover fall-hazards and learn about safety options to maintain your independence. Whether you need a picture hung or a total bathroom remodel, Call today for a FREE assessment! Monthy specials 317-216-0932 | geico.com/indianapolis for 55+ and Penny Stamps, CNA Veterans Home Safety Division Coordinator & Certified Aging in Place Specialist C: 317-800-4689 • P: 317.337.9334 • [email protected] 3837 N. -

Fedex Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview

FedEx Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview FedEx Corp. (NYSE: FDX) provides customers and businesses worldwide with a broad portfolio of transportation, e-commerce and business services. With annual revenues of $43 billion, the company offers integrated business applications through operating companies competing collectively and managed collaboratively, under the respected FedEx brand. Consistently ranked among the world’s most admired and trusted employers, FedEx inspires its more than 300,000 team members to remain “absolutely, positively” focused on safety, the highest ethical and professional standards and the needs of their customers and communities. For more information, go to news.fedex.com 2 Table of Contents FedEx Racing Commitment to Community ..................................................... 4-5 Denny Hamlin - Driver, #11 FedEx Toyota Camry Biography ....................................................................... 6-8 Career Highlights ............................................................... 10-12 2012 Season Highlights ............................................................. 13 2012 Season Results ............................................................... 14 2011 Season Highlights ............................................................. 15 2011 Season Results ............................................................... 16 2010 Season Highlights. 17 2010 Season Results ............................................................... 18 2009 Season Highlights ........................................................... -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 8 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 8A | ATLANTIC NEWS | AUGUST 5, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 31 ATLANTICNEWS.COM . TOWN NEWS ROLL CALL ROUND UP HOUSE Rye selectmen discuss beach issues (A,B) MALPRACTICE PANEL SHOULD COUNT AT TRIAL — SB214 would set up panels consisting of a judge, a BY JESSICA JENKINS The signs have been posted should be removed when surfers has increased sub- doctor and a lawyer, to screen out malpractice cases. A unan- SPECIAL TO THE ATLANTIC NEWS only when lifeguards are on guards are not on duty but stantially this year and it is imous decision against a case could be used in a jury trial. duty. This practice has come will seek confirmation from difficult in some cases to RYE | Beach Commis- Supporters of the bill argue that this panel — if its recom- sioner Peter Clark addressed into question since the the town attorney. Clark keep surfers well separated mendations could be heard by a jury — is an effective way of Rye selectmen at a recent recent tragedy at Hampton indicated that the selectmen from swimmers. screening out frivolous cases, which would help bring down meeting to ask if the recently Beach. will receive a letter com- As mentioned at other the cost of malpractice insurance. Opponents thought that posted rip tide signs should The selectmen agreed plaining about surfers. -

Mar-Apr 1984

March Sfienty April 1984 In 1979, Union Oil made the first dis- The Helm field, the first discovered, covery of oil offshore the Netherlands. is now producing from flve wells with IIri'i When this was followed by a second a sixth nearing completion. The discovery in 1980, commercial pro- Helder field produces from 12 wells. duction became a possibility-but And the Hoorn fleld, discovered in IVETHERLAIVDS only if the costs of development could 1982, produces from six wells. Costs be tightly controlled. incurred so far in the development The target date for production of of the Q/1 fields are in excess of one ll[[Sllm[ first oil was set for October 1982. Computer projections rated the 3lalil:n,gTud:d:xr:I:Cncgoer:i:egatvoe:aaguegsh- chances for such rapid completion of development very low, but this was to i`oTl::t,threegullderstooneus alongtime be no ordinary development process. The fields are all on the Q/I block, Working in close cooperation with its where Union has an 80 percent inter- C0mln joint-venture partner Nedlloyd, the est. The block covers about 75,000 Dutch government and Dutch contrac- acres and still has potential for new tors, Union beat the odds. discoveries, according to H. D. Max- wllHH First oil was produced in Septem- well, Union's regional vice president ber 1982 from the Helm and Helder headquartered in London. 'tsince 1967 Union and Nedlloyd fields, slightly ahead of schedule. The wail Hoom field began producing in August 1983, more than a month }9a,`;eo3C#:)do°fv;:oLp5fpe°ca°ryh::,i:::rs ahead of a very ambidous schedule. -

1968 Hot Wheels

1968 - 2003 VEHICLE LIST 1968 Hot Wheels 6459 Power Pad 5850 Hy Gear 6205 Custom Cougar 6460 AMX/2 5851 Miles Ahead 6206 Custom Mustang 6461 Jeep (Grass Hopper) 5853 Red Catchup 6207 Custom T-Bird 6466 Cockney Cab 5854 Hot Rodney 6208 Custom Camaro 6467 Olds 442 1973 Hot Wheels 6209 Silhouette 6469 Fire Chief Cruiser 5880 Double Header 6210 Deora 6471 Evil Weevil 6004 Superfine Turbine 6211 Custom Barracuda 6472 Cord 6007 Sweet 16 6212 Custom Firebird 6499 Boss Hoss Silver Special 6962 Mercedes 280SL 6213 Custom Fleetside 6410 Mongoose Funny Car 6963 Police Cruiser 6214 Ford J-Car 1970 Heavyweights 6964 Red Baron 6215 Custom Corvette 6450 Tow Truck 6965 Prowler 6217 Beatnik Bandit 6451 Ambulance 6966 Paddy Wagon 6218 Custom El Dorado 6452 Cement Mixer 6967 Dune Daddy 6219 Hot Heap 6453 Dump Truck 6968 Alive '55 6220 Custom Volkswagen Cheetah 6454 Fire Engine 6969 Snake 1969 Hot Wheels 6455 Moving Van 6970 Mongoose 6216 Python 1970 Rrrumblers 6971 Street Snorter 6250 Classic '32 Ford Vicky 6010 Road Hog 6972 Porsche 917 6251 Classic '31 Ford Woody 6011 High Tailer 6973 Ferrari 213P 6252 Classic '57 Bird 6031 Mean Machine 6974 Sand Witch 6253 Classic '36 Ford Coupe 6032 Rip Snorter 6975 Double Vision 6254 Lolo GT 70 6048 3-Squealer 6976 Buzz Off 6255 Mclaren MGA 6049 Torque Chop 6977 Zploder 6256 Chapparral 2G 1971 Hot Wheels 6978 Mercedes C111 6257 Ford MK IV 5953 Snake II 6979 Hiway Robber 6258 Twinmill 5954 Mongoose II 6980 Ice T 6259 Turbofire 5951 Snake Rail Dragster 6981 Odd Job 6260 Torero 5952 Mongoose Rail Dragster 6982 Show-off -

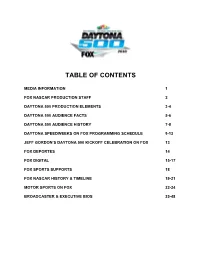

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb.