American Vaudeville As Ritual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

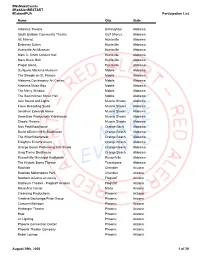

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

SWALI.ACK-8 THEATRE. V

v NEW-YORK DAILY TRIBUNE, SUNDAY, MARCH 7, 1900. iNEVV PLAYS THIS WEEK STAGE AFFAIRS MONDAY NIGHT. NEW AMSTERDAM THEATRE ACADEMY OF MUSIC.MUSIC Bnaasi W ACADEMY Mant^li begins engagement with revival of Frederic Thompson's production at "Bre»Eter> "KingJohn." rMillions" willb* the attraction at the Academy for night. LJ- RETURN ENGAGEMENTS. X ailianii period, beginning to-morrow \u25a0-,,,: Abel** Is the chief actor In that drama It ACADEMY OF MUSlC—Edward Abelea, In " ago. and " hod to. lor.p run hi this city two \u25a0"\u25a0\u25a0 "Prewster's Millions." In other Basana fr-.r.j successful engagements WEST END THEATRE -Mr. Faversham, In parts of Use tsottntry- to-night, "The World and His \Vlf<\" Hurr Slclntosh mta give a lecture here on "Cur Country." It w!l!be amply illustrated. LEADING PERFORMERS ON VARIETY STAGE- L< ASTOR THEATRE. Hodpe as the AMERICAN MUSIC HALL—Laurenc* Irvir*. "The Man from Hcme." with Mr. play, that have In "The Kin** and the Vagabond." principal actor, is one of the few beginning of the oe*- COLONIAL THEATRE- Mny Imin. In been on the boards since the "Mr?. favorite, Caraajsa-." wn. Itis BtHIa Pscknasa'a LINCOLN SQUARE THEATRE Jarri^s J. BELASCO THEATRE. Jeffries. Bau-^ »nU The FigLtir.K Hope" are *t'.V. VICTORIA THEATRE— Eva Tanguay and JilM nc*s at the Belasco. Afternoon performs Wllla Hoit \Vaken>!d Viialar of |!m t*if< a week. t:. 2UHh performance >U 'hat drama w-i!! occur shortly. RINGLING BROTHERS' CIRCUS. BIJOU THEATRE la Another "World's Greatest Due at Those r.h. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

A Career Overview 2019

ELAINE PAIGE A CAREER OVERVIEW 2019 Official Website: www.elainepaige.com Twitter: @elaine_paige THEATRE: Date Production Role Theatre 1968–1970 Hair Member of the Tribe Shaftesbury Theatre (London) 1973–1974 Grease Sandy New London Theatre (London) 1974–1975 Billy Rita Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London) 1976–1977 The Boyfriend Maisie Haymarket Theatre (Leicester) 1978–1980 Evita Eva Perón Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1981–1982 Cats Grizabella New London Theatre (London) 1983–1984 Abbacadabra Miss Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith Williams/Carabosse (London) 1986–1987 Chess Florence Vassy Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1989–1990 Anything Goes Reno Sweeney Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1993–1994 Piaf Édith Piaf Piccadilly Theatre (London) 1994, 1995- Sunset Boulevard Norma Desmond Adelphi Theatre (London) & then 1996, 1996– Minskoff Theatre (New York) 19981997 The Misanthrope Célimène Peter Hall Company, Piccadilly Theatre (London) 2000–2001 The King And I Anna Leonowens London Palladium (London) 2003 Where There's A Will Angèle Yvonne Arnaud Theatre (Guildford) & then the Theatre Royal 2004 Sweeney Todd – The Demon Mrs Lovett New York City Opera (New York)(Brighton) Barber Of Fleet Street 2007 The Drowsy Chaperone The Drowsy Novello Theatre (London) Chaperone/Beatrice 2011-12 Follies Carlotta CampionStockwell Kennedy Centre (Washington DC) Marquis Theatre, (New York) 2017-18 Dick Whttington Queen Rat LondoAhmansen Theatre (Los Angeles)n Palladium Theatre OTHER EARLY THEATRE ROLES: The Roar Of The Greasepaint - The Smell Of The Crowd (UK Tour) -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

Grumpy Old Humorist Tells All: Three Short Essays on Writing, Plus Random Thoughts on Same by Ed Mcclanahan

224 Ed McClanahan Grumpy Old Humorist Tells All: Three Short Essays On Writing, Plus Random Thoughts on Same by Ed McClanahan —“I can read readin’, but I can’t read writin’. The reason I can’t read writin’ is, it’s wrote too close to the paper.” —Clem Kadiddlehpopper When book reviewers deign to notice that I exist at all, they tend to refer to me as (among other lower life forms) a “humorist.” I’m always flattered, of course, to be nominated for the post, but I’m afraid I must politely decline to run, on the grounds that it would entail too much responsibility, trying to be funny all the time. The fact is, at my age, being funny ain’t really all that easy—or, to put it another way, being my age ain’t really all that funny . or, for that matter, all that easy either. We’ve all heard it said—usually of some poor, befuddled old bird like me—that “he’s taken leave of his senses.” What actually happens, though, is that our senses often pre- empt us to the punch, and take their own leave almost before we suspect they’re even contemplating a separation, much less a divorce. Corrective measures may, of course, sometimes be taken; cataract surgery is a wonder and a marvel, and I suppose there’s probably one of those “almost invisible” hearing aids circling my head at this very mo- ment, looking for an ear to build its unsightly nest in. My sense of smell has long since abandoned me (an impairment which, having its own occasional compensations, doesn’t even qualify me for disability assistance); and when it left, it took with it a disheartening measure of my sense of taste—so that, at dinnertime, I sit there grieving silently while everyone else is saying grace. -

“The Grin of the Skull Beneath the Skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 12-2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Drake, Amanda D., "“The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 57. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature by Amanda D. Drake A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy English Nineteenth-Century Studies Under the Supervision of Professor Stephen Behrendt Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” 1 Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Dr. Stephen Behrendt Neither representative of aesthetic flaws or mere comic relief, comic characters within Gothic narratives challenge and redefine the genre in ways that open up, rather than confuse, critical avenues. -

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, Collector. Theatrical

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, collector. Theatrical memorabilia, 1770-1940. 15 linear ft. (ca. 12,800 items in 32 boxes). Biography: Proprietor of Rare Old Programs, Newtonville, Mass. Summary: Theatrical memorabilia such as programs, playbills, photographs, engravings, and prints. Although there are some playbills as early as 1770, most of the material is from the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to plays there is some material relating to concerts, operettas, musical comedies, musical revues, and movies. The majority of the collection centers around Shakespeare. Included with an unbound copy of each play (The Edinburgh Shakespeare Folio Edition) there are portraits, engravings, and photographs of actors in their roles; playbills; programs; cast lists; other types of illustrative material; reviews of various productions; and other printed material. Such well known names as George Arliss, Sarah Bernhardt, the Booths, John Drew, the Barrymores, and William Gillette are included in this collection. Organization: Arranged. Finding aids: Contents list, 19p. Restrictions on use: Collection is shelved offsite and requires 48 hours for access. Available for faculty, students, and researchers engaged in scholarly or publication projects. Permission to publish materials must be obtained in writing from the Librarian for Rare Books and Manuscripts. 1. Arliss, George, 1868-1946. 2. Bernhardt, Sarah, 1844-1923. 3. Booth, Edwin, 1833-1893. 4. Booth, John Wilkes, 1838-1865. 5. Booth, Junius Brutus, 1796-1852. 6. Drew, John, 1827-1862. 7. Drew, John, 1853-1927. 8. Barrymore, Lionel, 1878-1954. 9. Barrymore, Ethel, 1879-1959. 10. Barrymore, Georgiana Drew, 1856- 1893. 11. Barrymore, John, 1882-1942. 12. Barrymore, Maurice, 1848-1904. -

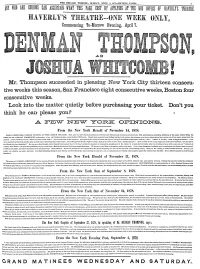

WEEK ONLY, Commencing To-Morrow Evening, April 7

CHICAGO THE TRIBUNE; SUNDAY, APRIL 6, 1879—SIXTEEN PAGES 9 ffl 100 ABE COBBS till ASCEBTAI MAT THIS PACE COST BY APFLTHS AT T 1 601 HFFH OF MBITS mm HAYEELT’S THEATRE—ONE WEEK ONLY, Commencing To-Morrow Evening, April 7. Ilplk ipii lAM A |«| f A BftK m E NM >|i 0 PSO D AS H M N 1 Jjjgglil ! i||j|i J||m||| ||g%| Bapa pgsa W#M m p|i fig lliiifmof p|| |||| ||||i 1111 PIS ilisL^Jli^ p|i I |j| mWk ii gy«sL JR*J# lit&fi-® iSswil&wt|||ij l|Bj bJ||||£ asiS|Li BJsliPLjHH &pkjggf -JiiwJiiPs_Js|iL Jggii jigii JOSrfTf lir yM Mr. Thompson succeeded in pleasing New York City thirteen consecu- tive weeks this season, San Francisco eight consecutive weeks, Boston four consecutive weeks. Look into the matter quietly before purchasing your ticket. Don’t you think he can please you? FEW- n-ew toke: oiraisrioisns- From tlie Sew York Herald of Soyemlber 11, 1878. JOSHUA WHITCOMB, YANKEE FARMER, AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE. They gave out gilt-edged programmes at the Lyceum Theatre last evening to celebrate the 70th performance, excluding matinees, of the piece which forma the setting for Mr. DENMAN THOMPSON’S delineation of an old Yankee fanner, yclept Joshua Whitcomb. People have recently been finding out that such a piece was running over there, where pieces have never run of late years, except into the ground. Aman would say to you, “Have you seen Uncle Josh?” You would reply in the negative. Straightway he would broaden into a grin—the grin of tickled recollection—and say, “Go." “What is he like; what is the piece about?” “Oh, never mind about the piece and the plot, and all that critical flummery that keeps a man asking himself if he ought to laugh; just go and roar at him; he’s a Yankee farmer.” After a week or two a man stops you in the streetand says, “Do you know that Bergh has been laughing?” Having seen that Knight of the Itueful Countenance rise in the Court of Special Sessions to demand thepunishment of the father ot a half-starved family, who was working a horse with a sore ear, an “unheard-of cruelty.