Labour Markets and Firm-Specific Capital in New Keynesian General Equilibrium Models*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy: Classicals, post-Keynesians and the New Keynesian Consensus Peter Kriesler and Marc Lavoie1 Abstract The paper looks at the adjustment process towards long run equilibrium within Marxian models, defined in terms of normal rates of capacity utilization. The model is reduced to three essential equations: an IS equation, a Phillips curve equation and an central bank reaction function. It is shown that long run convergence depends on the specific inflation (Phillips curve) equation, and on the central bank setting a zero inflationary target. When these conditions are relaxed, the results are shown to accord more closely with post-Keynesian results. The Marxian model is then contrasted with New Consensus models, which only varies in its inflation/Phillips curve equation. Post-Keynesian criticisms of both the IS and the Phillips curve equation are considered, and suggestions for a post-Keynesian alternative are made. Keywords: monetary policy, central bank, inflation, capacity utilization, post-Keynesian, New- Keynesian JEL classification: E12, E40, E52, E58 In an extremely interesting paper, Duménil and Lévy (Duménil and Lévy 1999) explore the adjustment mechanism of an economy towards a long run equilibrium with capacity utilization at normal levels − a fully adjusted position as the Sraffians would call it, or a classical long-term equilibrium as Duménil and Lévy have it. Short run equilibrium within their model is of the Keynes/Kalecki type, with variability in levels of capacity utilization. One distinctive feature of their model is that it is not the forces of competition which push the economy to a fully adjusted position, but rather aspects of the macro economy coupled with the behaviour of the central bank. -

Chapter 9 Gross Fixed Capital Formation

Gross fixed capital formation Chapter 9 Gross fixed capital formation Introduction 9.1 In the Income and Expenditure Accounts (IEA), gross fixed capital formation is divided into three principal types of investment expenditure: • residential structures; • non-residential structures; and • machinery and equipment. 9.2 Estimates of each type of investment are produced for the business1 and government sectors in the IEA. The discussion in this chapter is structured around these three major categories of gross fixed capital formation. 9.3 Fixed investment expenditure is a significant part of aggregate demand. This activity is tied to economic growth through its impact on the productive stock of capital, to social welfare in relation to government infrastructure, and to business cycles in terms of the volatility of its components. Concepts and definitions 9.4 Defining capital and capital expenditure is increasingly challenging, given the changing nature of production. Recently, the investment boundary has shifted, resulting in the re-classification of certain types of current expenditure to capital expenditure (e.g., software). In the simplest terms, any expenditure that gives rise to an asset could be considered investment; or, spending on an item whose expected life equals or exceeds one year could be considered investment. However, investment spending must be linked to future use in production.2 9.5 Fixed capital covers tangible or intangible assets which are produced as outputs from production processes and which are themselves used repeatedly or continuously in other production processes for more than one year. Fixed assets exclude, by definition, certain non-produced intangible assets, such as non-cultivated biological resources (e.g., virgin forests).3 9.6 Generally speaking, capital formation refers to additions to the stock of the nation’s non-financial assets resulting from investment activities. -

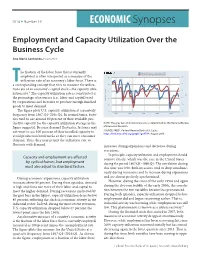

Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle

2016 n Number 19 ECONOMIC Synopses Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle Ana Maria Santacreu, Economist he fraction of the labor force that is currently Capacity Utilization: Total Industry (left) 100-Civilian Unemployment Rate (right) 98 employed is often interpreted as a measure of the 90 utilization rate of an economy’s labor force. There is 96 T 85 a corresponding concept that tries to measure the utiliza- tion rate of an economy’s capital stock—the capacity utili- 94 80 zation rate.1 The capacity utilization rate is constructed as 100-% 92 the percentage of resources (i.e., labor and capital) used 75 Percent of Capacity by corporations and factories to produce enough finished 90 goods to meet demand. 70 88 The figure plots U.S. capacity utilization at a quarterly 65 frequency from 1967:Q1–2016:Q1. In normal times, facto- 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 ries tend to use around 80 percent of their available pro- fred.stlouisfed.org myf.red/g/6ZXZ ductive capacity (as the capacity utilization average in the NOTE: The gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau figure suggests). Because demand fluctuates, factories may of Economic Research. SOURCE: FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; not want to use 100 percent of their installed capacity to https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=6TA4; August 2016. avoid production bottlenecks so they can meet consumer demand. Thus, they may permit the utilization rate to fluctuate with demand. increases during expansions and decreases during recessions. In principle, capacity utilization and employment should Capacity and employment are affected comove closely, which was the case in the United States by cyclical factors, but employment during the period 1967:Q1–1990:Q1. -

CHAPTER 6: PRIVATE FIXED INVESTMENT (Updated: December 2020)

CHAPTER 6: PRIVATE FIXED INVESTMENT (Updated: December 2020) Definitions and Concepts Recording in the NIPAs Overview of Source Data and Estimating Methods Benchmark-year estimates Nonbenchmark-year estimates Current quarterly estimates Quantity and price estimates Table 6.A—Summary of Methodology for Private Fixed Investment in Structures Table 6.B—Summary of Methodology for Private Fixed Investment in Equipment Table 6.C—Summary of Methodology for Private Fixed Investment in Intellectual Property Products Technical Note: Special Estimates New single-family structures Used equipment Intellectual property products Private fixed investment (PFI) measures spending by private businesses, nonprofit institutions, and households on fixed assets in the U.S. economy. Fixed assets consist of structures, equipment, and intellectual property products that are used in the production of goods and services. PFI encompasses the creation of new productive assets, the improvement of existing assets, and the replacement of worn out or obsolete assets. The PFI estimates serve as an indicator of the willingness of private businesses and nonprofit institutions to expand their production capacity and as an indicator of the demand for housing. Thus, movements in PFI serve as a barometer of confidence in, and support for, future economic growth. PFI also provides comprehensive information on the composition of business fixed investment. Thus, for example, it can be used to assess the penetration of new technology. In addition, the investment estimates are the building blocks for BEA’s estimates of capital stock, which are used in measuring rates of return on capital and in analyzing multifactor productivity. The PFI estimates are an integral part of the U.S. -

Imbalance Game 2.0: a Tale of Two Productivities

NEW THINKING Imbalance Game 2.0: A Tale of Two Productivities Michael Craig, CFA Vice President & Director Haining Zha, CFA Vice President September 2017 Almost nine years after the financial crisis, the global economy remains mired in low growth. Low productivity growth is certainly a key contributing factor, but our research shows that current productivity measures don’t tell the whole story. In this article, we propose a fundamental change to how people should examine productivity: we believe the supply and demand sides should be viewed separately to obtain more robust insights. Taking this approach allows us to differentiate supply-side progress from demand-side malaise and shows that the economy may be more promising than commonly thought. In addition, it highlights large supply-side divergences within and across different sectors of the economy, which are not reflected in the aggregate productivity measure – potentially leading to a distorted economic picture. Viewing productivity through this new lens, we believe that: • Nominal economic growth will remain low • Inflation will remain subdued • Interest rates will stay lower for longer • Technology-driven progress and persistent supply-side divergence will create investment risks and opportunities in equity markets In the investment world, economic growth is a big deal. We believe investment returns across asset classes can ultimately be traced back to one source: economic growth. Occasionally, asset prices can deviate from fundamentals, but over the long term, the relationship between returns and growth is very strong. That’s why it is critical to have a better understanding of the low growth phenomenon and key contributing factors, such as productivity. -

15 Theories of Investment Expenditures

Economics 314 Coursebook, 2010 Jeffrey Parker 15 THEORIES OF INVESTMENT EXPENDITURES Chapter 15 Contents A. Topics and Tools ..............................................................................2 B. How Firms Invest ............................................................................2 What investment is and what it is not ............................................................................ 2 Financing of investment ................................................................................................ 3 The Modigliani-Miller theorem ..................................................................................... 5 Sources of finance and credit availability effects ............................................................... 6 C. Investment and the Business Cycle ...................................................... 8 Keynes and the business cycle ........................................................................................ 8 The accelerator theory of investment ............................................................................... 9 The multiplier-accelerator model .................................................................................. 10 D. Understanding Romer’s Chapter 8 ..................................................... 12 The firm’s profit function ............................................................................................ 13 User cost of capital ..................................................................................................... -

The Flexible Accelerator Model of Investment: an Application to Ugandan Tea-Processing Firms

African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics Volume 10 Number 1 pages 1-15 The flexible accelerator model of investment: An application to Ugandan tea-processing firms *Edgar E. Twine International Livestock Research Institute, c/o IITA East Africa Hub, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. E-mail: [email protected] Barnabas Kiiza Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. E-mail: [email protected] Bernard Bashaasha Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The study uses the flexible accelerator model to examine determinants of the level and growth of investment in machinery and equipment for a sample of tea-processing firms in Uganda. Using a dynamic panel data model, we find that, in the long run, the level of investment in machinery and equipment is positively influenced by the accelerator, firm-level liquidity, and a favourable investment climate in the country. Depreciation of the exchange rate negatively affects investment. We conclude that firm-level strategies that increase output and profitability, and a favourable investment policy climate, are imperative to the growth of the tea industry. Key words: accelerator model; fixed asset investments; Ugandan tea-processing firms 1. Introduction Investment or capital accumulation is widely regarded as important in raising output and income at both the firm and national level. The private sector in Uganda has responded to macroeconomic policy reforms with private investment increasing by 13% per year on average from 1986/1987 to 1997/1998 (Collier & Reinikka 2001). The sectors that have attracted most investment in recent years are manufacturing, agriculture, forestry, fishing, construction and services. -

Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues

Working Paper No. 952 Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues by Michalis Nikiforos* Levy Economics Institute of Bard College April 2020 * For useful comments, the author would like to thank participants at the 45th annual Eastern Economic Association conference in New York and those at the 23rd Forum for Microeconomics and Macroeconomics conference in Berlin. The usual disclaimer applies The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2020 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT This paper discusses some issues related to the triangle between capital accumulation, distribution, and capacity utilization. First, it explains why utilization is a crucial variable for the various theories of growth and distribution—more precisely, with regards to their ability to combine an autonomous role for demand (along Keynesian lines) and an institutionally determined distribution (along classical lines). Second, it responds to some recent criticism by Girardi and Pariboni (2019). I explain that their interpretation of the model in Nikiforos (2013) is misguided, and that the results of the model can be extended to the case of a monopolist. -

The Great Depression As a Historical Problem

Upjohn Institute Press The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego Chapter 3 (pp. 63-94) in: The Economics of the Great Depression Mark Wheeler, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1998 DOI: 10.17848/9780585322049.ch3 Copyright ©1998. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. 3 The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego It is now over a half-century since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the most severe and protracted economic crisis in American his tory. To this day, there exists no general agreement about its causes, although there tends to be a consensus about its consequences. Those who at the time argued that the Depression was symptomatic of a pro found weakness in the mechanisms of capitalism were only briefly heard. After World War II, their views appeared hysterical and exag gerated, as the industrialized nations (the United States most prominent among them) sustained dramatic rates of growth and as the economics profession became increasingly preoccupied with the development of Keynesian theory and the management of the mixed economy. As a consequence, the economic slump of the inter-war period came to be viewed as a policy problem rather than as an outgrowth of fundamental tendencies in capitalist development. Within that new context, a debate persisted for a few years, but it too eventually subsided. The presump tion was that the Great Depression could never be repeated owing to the increasing sophistication of economic analysis and policy formula tion. -

Capacity and Capacity Utilization in Fishing Industries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by College of William & Mary: W&M Publish W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Books and Book Chapters Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2003 Capacity And Capacity Utilization In Fishing Industries James E. Kirkley Dale Squires Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Extracted from : Pascoe, S.; Gréboval, D. (eds.) Measuring capacity in fisheries. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 445. Rome, FAO. 2003. 314p. http://www.fao.org/3/Y4849E/y4849e00.htm http://www.fao.org/3/Y4849E/y4849e04.htm#bm04 CAPACITY AND CAPACITY UTILIZATION IN FISHING INDUSTRIES – James E. Kirkley[24] and Dale Squires[25] Abstract: The definition and measurement of capacity in fishing and other natural resource industries possess unique problems because of the stock-flow production technology, in which inputs are applied to the natural resource stock to produce a flow of output. In addition, there are often multiple resource stocks, corresponding to different species, with a mobile stock of capital that can exploit one or more of these stocks. In turn, this leads to three unique issues: (1) multiple stocks of capital and the resource; (2) that of aggregation or how to define the industry and resource stocks to consider; and (3), that of latent capacity or how to include stocks of capital that are currently inactive or exploit the resource stock only at low levels of variable input utilization. This paper presents appropriate definitions of capacity and methods for measuring capacity in fishing industries taking into consideration these issues. -

Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aloi, Marta; Dixon, Huw D. Working Paper Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy CESifo Working Paper, No. 716 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Aloi, Marta; Dixon, Huw D. (2002) : Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy, CESifo Working Paper, No. 716, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/75945 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu A joint Initiative of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and Ifo Institute for Economic Research Working Papers ENTRY DYNAMICS, CAPACITY UTILISATION AND PRODUCTIVITY IN A DYNAMIC OPEN ECONOMY* Marta Aloi Huw Dixon CESifo Working Paper No. -

Fixed-Assets-1925-97.Pdf

SEPTEMBER 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Donald L. Evans, Secretary ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS ADMINISTRATION ECONOMICS Kathleen B. Cooper, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs AND STATISTICS ADMINISTRATION BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS J. Steven Landefeld, Director Rosemary D. Marcuss, Deputy Director www.bea.gov i Suggested Citation U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Fixed Assets and Consumer Durable Goods in the United States, 1925–99. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, September, 2003. ii Acknowledgments This publication was written by Shelby W. Herman, and Randal T. Matsunaga oversaw preparation of the Arnold J. Katz, Leonard J. Loebach, and Stephanie H. published volume. Barbara M. Fraumeni, BEA’s Chief McCulla with assistance from Michael D. Glenn. The Economist, recommended the depreciation profiles that estimates of fixed assets and consumer durables were were used. prepared by the National Income and Wealth Division Overall supervision was provided by Carol Moylan, and the Government Division of BEA. Specifically, the Chief of the National Income and Wealth Division; by estimates for the private sector and the chain-type esti- Karl Galbraith, former Chief of the Government Divi- mates for the private and government sectors were pre- sion; by Brooks B. Robinson, Chief of the Government pared by Michael D. Glenn, Phyllis Barnes, Kurt Kunze, Division; and by Brent R. Moulton, Associate Director Leonard J. Loebach, and Dennis R. Weikel, under the for National Economic Accounts. Kristina Maze edited direction of Shelby W. Herman. The estimates for the the volume and W. Ronnie Foster of Publication Ser- government sector were prepared by Charles S.