A Complete Database of International Chess Players and Chess Performance Ratings for Varied Longitudinal Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

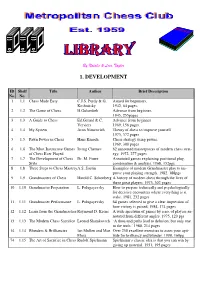

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2015 1

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2015 1. Organisation 1.1 The FIDE World Chess Cup (World Cup) is an integral part of the World Championship Cycle 2014-2016. 1.2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1.3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the World Chess Cup 2015, including internet rights. 1.4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. Qualifying Events for World Cup 2015 2. 1. National Chess Championships - National Chess Championships are the responsibility of the Federations who retain all rights in their internal competitions. 2. 2. Zonal Tournaments - Zonals can be organised by the Continents according to their regulations that have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. 3. Continental Chess Championships - The Continents, through their respective Boards and in co-operation with FIDE, shall organise Continental Chess Championships. The regulations for these events have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board nine months before they start if they are to be part of the qualification system of the World Chess Championship cycle. 2. 3. 1. FIDE shall guarantee a minimum grant of USD 92,000 towards the total prize fund for Continental Championships, divided among the following continents: 1. Americas 32,000 USD (minimum prize fund in total: 50,000 USD) 2. -

Chess2vec: Learning Vector Representations for Chess

Chess2vec: Learning Vector Representations for Chess Berk Kapicioglu Ramiz Iqbal∗ Tarik Koc OccamzRazor MD Anderson Cancer Center OccamzRazor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Louis Nicolas Andre Katharina Sophia Volz OccamzRazor OccamzRazor [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We conduct the first study of its kind to generate and evaluate vector representations for chess pieces. In particular, we uncover the latent structure of chess pieces and moves, as well as predict chess moves from chess positions. We share preliminary results which anticipate our ongoing work on a neural network architecture that learns these embeddings directly from supervised feedback. 1 Introduction In the last couple of years, advances in machine learning have yielded dramatic improvements in tasks as diverse as visual object classification [9], automatic speech recognition [7], machine translation [18], and natural language processing (NLP) [12]. A common thread among all these tasks is, as diverse as they may seem, they all involve processing input data, such as image, audio, and text, that have not traditionally been amenable to feature engineering. Modern machine learning methods that enabled these breakthroughs did so partly because they shifted the burden away from feature engineering, which is difficult for humans and requires domain expertise, towards designing models that automatically infer feature representations that are relevant for downstream tasks [1]. In this paper, we are interested in learning and studying feature representations of chess positions and pieces. Our work is inspired by how learning vector representation of words [12, 13], also known as word embeddings, yielded improvements in tasks such as syntactic parsing [16] and sentiment analysis [17]. -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2017 2. Qualifying Events for World Cup 2017

Regulations for the FIDE World Chess Cup 2017 1. Organisation 1.1 The FIDE World Chess Cup (World Cup) is an integral part of the World Championship Cycle 2016-2018. 1.2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1.3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the World Chess Cup 2017, including internet rights. 1.4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. Qualifying Events for World Cup 2017 2. 1. National Chess Championships - National Chess Championships are the responsibility of the Federations who retain all rights in their internal competitions. 2. 2. Zonal Tournaments - Zonals can be organised by the Continents according to their regulations that have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board. 2. 3. Continental Chess Championships - The Continents, through their respective Boards and in co-operation with FIDE, shall organise Continental Chess Championships. The regulations for these events have to be approved by the FIDE Presidential Board nine months before they start if they are to be part of the qualification system of the World Chess Championship cycle. 2. 3. 1. FIDE shall guarantee a minimum grant of USD 92,000 towards the total prize fund for Continental Championships, divided among the following continents: 1. Americas 32,000 USD (minimum prize fund in total: 50,000 USD) 2. -

Life Cycle Patterns of Cognitive Performance Over the Long

Life cycle patterns of cognitive performance over the long run Anthony Strittmattera,1 , Uwe Sundeb,1,2, and Dainis Zegnersc,1 aCenter for Research in Economics and Statistics (CREST)/Ecole´ nationale de la statistique et de l’administration economique´ Paris (ENSAE), Institut Polytechnique Paris, 91764 Palaiseau Cedex, France; bEconomics Department, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ 80539 Munchen,¨ Germany; and cRotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, 3062 PA Rotterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Robert Moffit, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jose A. Scheinkman September 21, 2020 (received for review April 8, 2020) Little is known about how the age pattern in individual perfor- demanding tasks, however, and are limited in terms of compara- mance in cognitively demanding tasks changed over the past bility, technological work environment, labor market institutions, century. The main difficulty for measuring such life cycle per- and demand factors, which all exhibit variation over time and formance patterns and their dynamics over time is related to across skill groups (1, 19). Investigations that account for changes the construction of a reliable measure that is comparable across in skill demand have found evidence for a peak in performance individuals and over time and not affected by changes in technol- potential around ages of 35 to 44 y (20) but are limited to short ogy or other environmental factors. This study presents evidence observation periods that prevent an analysis of the dynamics for the dynamics of life cycle patterns of cognitive performance of the age–performance profile over time and across cohorts. over the past 125 y based on an analysis of data from profes- An additional problem is related to measuring productivity or sional chess tournaments. -

A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague – Candidates Tournament 2020

A FEAST OF CHESS IN TIME OF PLAGUE CANDIDATES TOURNAMENT 2020 Part 1 — Yekaterinburg by Vladimir Tukmakov www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniël Vanheirzeele Translator Izyaslav Koza Proofreader Bob Holliman Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Mieke Mertens Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague. Candidates Tournament 2020. Part 1 — Yekaterinburg Copyright © 2020 Vladimir Tukmakov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-092-1 D/2020/13730/26 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PRELUDE 11 THE PLAY Round 1 21 Round 2 44 Round 3 61 Round 4 80 Round 5 94 Round 6 110 Round 7 127 Final — Round 8 141 UNEXPECTED CONCLUSION 143 INTERIM RESULTS 147 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! a good move ?a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move only move =equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrifi ced material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage Black has a serious advantage +– White has a decisive advantage –+ Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is worse is Nnovelty +check #mate INTRODUCTION In the middle of the last century tournament compilations were ex- tremely popular. -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Vasily Smyslov

Vasily Smyslov Volume I The Early Years: 1921-1948 Andrey Terekhov Foreword by Peter Svidler Smyslov’s Endgames by Karsten Müller 2020 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Vasily Smyslov Volume I The Early Years: 1921-1948 ISBN: 978-1-949859-24-9 (print) ISBN: 949859-25-6 (eBook) © Copyright 2020 Andrey Terekhov All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Fierce Ponies Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Introduction 6 Acknowledgments 9 Foreword by Peter Svidler 11 Signs and Symbols 13 Chapter 1. First Steps – 1935-37 14 Parents and Childhood 14 Chess Education at Home 18 The First Tournaments 22 The First Publications 26 The First Victories over Masters 34 Chapter 1: Games 41 Chapter 2. The Breakthrough Year – 1938 49 USSR Junior Championship 49 The First Adult Tournaments 53 The Higher Education Quandary 54 Candidate Master 56 1938 Moscow Championship 62 Chapter 2: Games 67 Chapter 3. The Young Master – 1939-40 80 1939 Leningrad/Moscow Training Tournament 80 The Run-Up to the 1940 USSR championship 87 Chapter 3: Games 91 Chapter 4. Third in the Soviet Union – 1940 118 World Politics and Chess 118 Pre-Tournament Forecasts 121 Round-By-Round Overview 126 After the Tournament 146 Chapter 4: Games 151 3 Chapter 5.