Does It Make a Difference? an Exploratory Study Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 ALPS TOUR QUALIFYING SCHOOL for the 2019 Season

2018 ALPS TOUR QUALIFYING SCHOOL For the 2019 season First Qualifying Stage: 9th & 10th December 2018 Final Qualifying Stage: 13th, 14th & 15th December 2018 1. FORMAT The school will be conducted in two stages of stroke play. FIRST QUALIFYING STAGE: (36 holes scheduled) – Sunday 9th & Monday 10th December 2018 This applies to all applicants except those who have automatically qualified for the Final Stage. First Stage will be played on 9th and 10th December 2018 at the following venue: La Cala Resort « ASIA Course » « AMERICA Course » « EUROPA Course » Urb. La Cala Golf s/n Costa de Mijas – 29649 Malaga SPAIN +34 952 669 033 +34 952 669 023 [email protected] www.lacala.com Malaga (39 km) Malaga (47 km) In the event of a delay in completing the First Stage, applicants are advised that the Tuesday 11th December 2018 may be used as a full playing day in order to complete the competition. Applicants must indicate on the application form their venue preferences in order from 1 to 3. The Alps Tour takes account of each applicant’s venue preference where possible but the primary objective is to balance the number of applicants playing at each venue. In the event of any venue being oversubscribed, priority will initially be determined by the payment date of the entry fee. The first 50 paid up entries received by the Alps Tour for each venue will be allocated to that venue. Thereafter, applicants will be allocated the venue which is highest in their list of preferences and which has availability at the time the application form and payment are received. -

George Coetzee

George Coetzee Representerar Sydafrika (RSA) Född 1986-07-18 Status Proffs Huvudtour European Tour SGT-spelare Nej Aktuellt Ranking 2021 George Coetzee har i år spelat 14 tävlingar. Han har klarat 8 kval. På dessa 14 starter har det blivit 1 topp-10-placeringar. Som bäst har George Coetzee en 10-plats i Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors. Han har i år en snittscore om 70,48 efter att ha slagit 3101 slag på 44 ronder. George Coetzee har på de senaste starterna placeringarna 26-MC-MC-27-75 varav senaste starten var BMW PGA Championship. Han har i år som bästa score noterat 64 (-8) i Dimension Data Pro-Am på Fancourt Golf Estate. 20 av årets 44 ronder har varit under par. Vid 15 tillfällen har det noterats scorer på under 70 slag men också vid 1 tillfällen minst 75 slag. George Coetzee har klarat kvalet i de 2 senaste tävlingarna. Kvalsviten i år löper från DS Automobiles Italian Open (vecka 35/2021). Årets tävlingar Plac Tävling Plac Tävling Plac Tävling 75 BMW PGA Championship MC Dubai Duty Free Irish Open MC Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Wentworth Golf Club, European Tour Mount Juliet Estate, European Tour Education City GC, European Tour 27 DS Automobiles Italian Open MC PGA Championship 10 Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors Marco Simone GC, European Tour Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, PGA Tour Royal Greens G&CC, European Tour MC Omega European Masters 14 Dimension Data Pro-Am 60 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Crans-sur-Sierre GC, European Tour Fancourt Golf Estate, European Challenge Tour -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y

. OP U.S EN SHINNECOCK HILLS TH 118TH U.S. OPEN PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y. — June 14-17, 2018 conducted by the 2018 U.S. OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List SHOTA AKIYOSHI Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying for the 118th U.S. Open Championship, with their exemption categories Shota Akiyoshi is 183 in this week’s Official World Golf Ranking listed. Birth Date: July 22, 1990 Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kumamoto, Japan Kiradech Aphibarnrat 13 Marc Leishman 12, 13 Age: 27 Ht.: 5’7 Wt.: 190 Daniel Berger 12, 13 Alexander Levy 13 Home: Kumamoto, Japan Rafael Cabrera Bello 13 Hao Tong Li 13 Patrick Cantlay 12, 13 Luke List 13 Turned Professional: 2009 Paul Casey 12, 13 Hideki Matsuyama 11, 12, 13 Japan Tour Victories: 1 -2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Kevin Chappell 12, 13 Graeme McDowell 1 Open. Jason Day 7, 8, 12, 13 Rory McIlroy 1, 6, 7, 13 Bryson DeChambeau 13 Phil Mickelson 6, 13 Player Notes: ELIGIBILITY: He shot 134 at Japan Memorial Golf Jason Dufner 7, 12, 13 Francesco Molinari 9, 13 Harry Ellis (a) 3 Trey Mullinax 11 Club in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, to earn one of three spots. Ernie Els 15 Alex Noren 13 Shota Akiyoshi started playing golf at the age of 10 years old. Tony Finau 12, 13 Louis Oosthuizen 13 Turned professional in January, 2009. Ross Fisher 13 Matt Parziale (a) 2 Matthew Fitzpatrick 13 Pat Perez 12, 13 Just secured his first Japan Golf Tour win with a one-shot victory Tommy Fleetwood 11, 13 Kenny Perry 10 at the 2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Open. -

2020-21 Men's Golf

U NIVERSITY OF I LLINOIS 2020-21 MEN’S GOLF TABLE OF CONTENTS Head Coach Mike Small ����������������������������������������2-7 Assistant Coach Justin Bardgett / Director of Operations Jackie Szymoniak���8 Michael Feagles �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9-10 Giovanni Tadiotto . .11-12 Brendan O’Reilly � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Luke Armbrust� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �14 Adrien Dumont de Chassart ��������������������������������������15 Tommy Kuhl ��������������������������������������������������16 Jerrry Ji ������������������������������������������������������17 Nico Lang ����������������������������������������������������18 Piercen Hunt ��������������������������������������������������19 Olympia Fields Country Club Fighting Illini Invitational �����������������20 2019-20 Review . 21-22 2019-20 Results/Statistics������������������������������������23-27 Team Records ����������������������������������������������28-29 Individual Records . 30-32 Big Ten Championships Results �����������������������������������33 2020-21 ILLINOIS MEN’S GOLF ROSTER NCAA Regional & NCAA Championships Results�����������������������34 Name Year Hometown / Previous School Individual Honors �������������������������������������������34-36 Luke Armbrust Jr� Wheaton, Illinois/St� Francis All-Time Letterwinners ���������������������������������������37-38 Adrien Dumont -

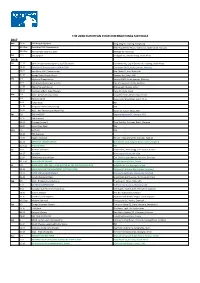

2017 2018 the 2018 European Tour International Schedule

THE 2018 EUROPEAN TOUR INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE 2017 Nov 23-26 UBS Hong Kong Open Hong Kong GC, Fanling, Hong Kong 30-3 Dec Australian PGA Championship RACV Royal Pines Resort, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia 30-3 Dec AfrAsia Bank Mauritius Open Heritage GC, Mauritius Dec 7-10 Joburg Open Randpark GC, Johannesburg, South Africa 2018 Jan 11-14 BMW SA Open hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni Glendower GC, City of Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, South Africa 12-14 EURASIA CUP presented by DRB-HICOM Glenmarie G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 18-21 Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship Abu Dhabi GC, Abu Dhabi, UAE 25-28 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Emirates GC, Dubai, UAE Feb 1-4 Maybank Championship Saujana G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 8-11 ISPS Handa World Super 6 Perth Lake Karrinyup CC, Perth, Australia 15-18 NBO Oman Golf Classic Almouj Golf, Muscat, Oman 22-25 Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Doha GC, Doha, Qatar Mar 1-4 WGC - Mexico Championship Chapultepec GC, Mexico City, Mexico 1-4 Tshwane Open Pretoria CC, Waterkloof, South Africa 8-11 Indian Open TBA 15-18 Philippines Golf Championship TBA 21-25 WGC - Dell Technologies Match Play Austin CC, Austin, Texas, USA Apr 5-8 THE MASTERS Augusta National GC, Georgia, USA 12-15 TBA (Europe) 19-22 Trophee Hassan II Royal Golf Dar Es Salam, Rabat, Morocco 26-29 Volvo China Open TBA May 5-6 GolfSixes TBA 10-13 TBA (Europe) 17-20 Belgian Knockout Rinkven International GC, Antwerp, Belgium 24-27 BMW PGA CHAMPIONSHIP Wentworth Club, Virginia Water, Surrey, England 31-3 Jun ITALIAN OPEN TBA Jun 7-10 Austrian Golf Open Diamond CC, Atzenbrugg, near Vienna, Austria 14-17 US OPEN Shinnecock Hills GC, NY, USA 21-24 BMW International Open Golf Club Gut Laerchenhof, Pulheim, Germany 28-1 Jul HNA OPEN DE FRANCE Le Golf National, Paris, France Jul 5-8 DUBAI DUTY FREE IRISH OPEN HOSTED BY THE RORY FOUNDATION Ballyliffin GC, Co. -

2017-2018 Player Handbook & Tournament Regulations

2017-2018 PLAYER HANDBOOK & TOURNAMENT REGULATIONS PGA TOUR 112 PGA TOUR Boulevard Ponte Vedra Beach, FL 32082 Telephone: 904/285-3700 Dear PGA TOUR members, Welcome to the PGA TOUR. This directory was compiled to assist you in your preparation for a season on the PGA TOUR. The Player Handbook includes a 2017-2018 tournament schedule and covers such top- ics as special event eligibility and special awards. The Tournament Regulations are the guide to specific rules pertaining to PGA TOUR play. We have incorporated changes made to the Tournament Regulations since last season into this season’s book. In addition, the index provides quick reference. These Regulations are the final authority on the operations and policies of the PGA TOUR. I encourage every member to become familiar with these rules. Best wishes for a successful 2017-2018 season! Jay Monahan Commissioner PGA TOUR SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FOR THE 2017-2018 SEASON • Elimination of the Official Money List Leader exemption beginning with the leader of the 2016-2017 season. • The Top 125 Official Money List category has been eliminated. • Introduction of PGA TOUR Integrity program which among other things prohibits players from betting on professional golf. • Amendments to the Pace of Play Policy. • Amendments to the Player Endorsement Policy to exclude sponsorships by FedEx competitors. • Addition of an official pro-am format whereby one professional plays the first nine holes and a second professional plays the second nine holes. • Changes to the One New Event Played Per Season Requirement to exclude any first-year official money event. • Changes to the Ryder Cup points structure. -

Martin Kaymer

Martin Kaymer Representerar Tyskland (GER) Född Status Proffs Huvudtour European Tour SGT-spelare Nej Aktuellt Ranking 2021 Martin Kaymer har i år spelat 16 tävlingar. Han har klarat 8 kval. På dessa 16 starter har det blivit 2 topp-10-placeringar. Som bäst har Martin Kaymer en 2-plats i BMW International Open. Han har i år en snittscore om 71,02 efter att ha slagit 3409 slag på 48 ronder. Martin Kaymer har på de senaste starterna placeringarna MC-MC-18-MC-25 varav senaste starten var BMW PGA Championship. Han har i år som bästa score noterat 64 (-8) i BMW International Open på Golfclub München Eichenried. 24 av årets 48 ronder har varit under par. Vid 15 tillfällen har det noterats scorer på under 70 slag men också vid 2 tillfällen minst 75 slag. Årets tävlingar Plac Tävling Plac Tävling Plac Tävling 25 BMW PGA Championship 2 BMW International Open MC The Honda Classic Wentworth Golf Club, European Tour Golfclub München Eichenried, European Tour PGA National (Champion) , PGA Tour MC DS Automobiles Italian Open 26 U.S. Open 18 Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors Marco Simone GC, European Tour Torrey Pines (South), PGA Tour Royal Greens G&CC, European Tour 18 Omega European Masters MC Porsche European Open 44 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Crans-sur-Sierre GC, European Tour Green Eagle Golf Courses, European Tour Emirates GC, European Tour MC THE 149TH OPEN MC PGA Championship MC Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship presented by EGA Royal St George’s GC, European Tour Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, PGA Tour Abu Dhabi GC, European Tour MC abrdn Scottish Open MC Betfred British Masters hosted by Danny Willet The Renaissance Club, European Tour The Belfry, European Tour 41 Dubai Duty Free Irish Open 3 Austrian Open Mount Juliet Estate, European Tour Diamond CC, European Tour Karriären Totala prispengar 1997-2021 Martin Kaymer har följande facit så här långt i karriären: (officiella prispengar på SGT och världstourerna) Summa Största Snitt per 20 segrar på 404 tävlingar. -

A Rust Belt Synagogue ‘Runs out of Angeles and Was Composing Awards

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 19 JANUARY 12, 2018 25 TEVET, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ Artists-in-Residence event at Temple Israel Sam Glaser, one of Amer- ica’s foremost composers, performers and interpreters of Jewish music will be visit- ing Central Florida Jan. 19-21 as the Artist-in-Residence at Temple Israel and Temple Shir Shalom in Winter Springs. Both congregations invite the community to attend four events: A Reform-style musi- cal service and festive oneg on Friday, Jan. 19 at 7:30 p.m. (no charge); A Conservative-style musical service followed by kiddish and study with Glaser on Saturday, Jan. 20, at 10 a.m. (no charge); a Gala Concert presented by Temple Israel Sam Glaser with Temple Shir Shalom on Alanna E. Cooper Saturday, Jan. 20, at 7:30 p.m. Haneshama.” He performs an- Congregants from Temple Hadar Israel in New Castle, Pa., gathering at the local Tifereth Israel cemetery to bury ritual (tickets for purchase); and a nually before thousands and objects from their defunct synagogue, Dec. 31, 2017. free family concert on Sunday, has toured the world over, and Jan. 21 at 12:30 p.m. has won Parent’s Choice, John Glaser was born in 1962 Lennon, and International to a Jewish family in Los Songwriting Competition A Rust Belt synagogue ‘runs out of Angeles and was composing awards. and performing by the age of He produces music through seven. -

Michael Baliker

Onsite PGA TOUR media contact: Michael Baliker (864) 430-9801 [email protected] 2019 World Golf Championships-Mexico Championship Dates: February 18-24, 2019 Where: Club de Golf Chapultepec, Mexico City, Mexico Par/Yards: 35-36 – 71/7,345 yards 2018 champion: Phil Mickelson Purse: $10,250,000/$1,745,000 FedExCup: 550 points to the winner Format: 72-hole stroke play competition (no cut) Twitter: @WGCMexico Facebook: Facebook.com/wgcmexicochampionship Instagram: @WGCMexico Five Things to Know about the 2019 WGC-Mexico Championship 1. Woods’ first-ever start in Mexico: Woods, winner of a record 18 World Golf Championships in nine different locations, is set to play in his first-ever competitive event in Mexico. Two wins shy of Sam Snead’s all-time PGA TOUR record of 82, Woods is a seven-time winner of the tournament with victories in Spain, England, Ireland and the United States (San Francisco, suburban Atlanta and Miami). 2. Monster field: 28 of the 30 players that qualified for the 2018 TOUR Championship and 27 of the top 30 in the current Official World Golf Ranking are in the WGC-Mexico Championship field. 3. PGA TOUR in Mexico: The WGC-Mexico Championship is one of two current PGA TOUR events in Mexico along with the Mayakoba Golf Classic, which dates back to 2007. Part of the secret to winning at Club de Golf Chapultepec is properly determining the altitude’s role when choosing clubs. The lowest elevation of the Club de Golf Chapultepec is 7,603 feet above sea level and the highest part is at 7,835 feet. -

Pga Tour Player Handbook & Tournament Regulations 2018-2019

PGA TOUR PLAYER HANDBOOK & TOURNAMENT REGULATIONS 2018-2019 1 2018-2019 PLAYER HANDBOOK & TOURNAMENT REGULATIONS PGA TOUR 112 PGA TOUR Boulevard Ponte Vedra Beach, FL 32082 Telephone: 904/285-3700 Dear PGA TOUR members, Welcome to the PGA TOUR. This directory was compiled to assist you in your preparation for a season on the PGA TOUR. The Player Handbook includes a 2018-2019 tournament schedule and covers such top- ics as special event eligibility and special awards. The Tournament Regulations are the guide to specific rules pertaining to PGA TOUR play. We have incorporated changes made to the Tournament Regulations since last season into this season’s book. In addition, the index provides quick reference. These Regulations are the final authority on the operations and policies of the PGA TOUR. I encourage every member to become familiar with these rules. Best wishes for a successful 2018-2019 season! Jay Monahan Commissioner PGA TOUR SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FOR THE 2018-2019 SEASON • TOUR Championship format and FedExCup bonus structure changes including the addition of a bonus for the top 10 players from the Regular Season known as the "Wyndham Rewards Top 10". • Modifications to the World Cup of Golf withdrawal policy. • Changes to the 2019 Presidents Cup Eligibility. • Expanding the Top 50 Career Money Exemption to include players who have made 300 or more PGA TOUR cuts. • Inclusion of the FedExCup Champion in the Multi-Season Exemption Extension Rule. • The Shriners Hospitals for Children Open field size reduced to 132 from 144. • There will be five periodic reshuffles in the 2018-2019 season taking place following The RSM Classic and the Genesis Open, and thereafter, the Mondays of the Masters, the Memorial Tournament presented by Nationwide and The Open Championship. -

2018 Staysure Tour Order of Merit 2018

September 3, 2018 Top Ten in the 2018 Race to Dubai Matt Fitzpatrick 1 Francesco MOLINARI (ITA) Pts 4,635,909 2 Patrick REED (USA) 3,057,948 3 Tommy FLEETWOOD (ENG) 2,805,043 4 Rory MCILROY (NIR) 2,760,667 5 Alex NOREN (SWE) 2,729,725 6 Thorbjørn OLESEN (DEN) 2,459,412 7 Jon RAHM (ESP) 2,161,574 8 Russell KNOX (SCO) 2,054,929 9 Tyrrell HATTON (ENG) 1,892,819 10 Rafa CABRERA BELLO (ESP) 1,775,523 This Week on the European Tour Sept 6 - 9, 2018 Omega European Masters Crans-sur-Sierre Golf Club, Crans Montana, Switzerland 2017 CHAMPION: Matt Fitzpatrick (ENG) PRIZE FUND: €2,500,000 DID YOU KNOW? OMEGA EUROPEAN MASTERS • If Matthew Fitzpatrick were to successfully defend his Omega • Crans-sur-Sierre will be staging the tournament for the 72nd European Masters title this week, he would be the first person to do so successive time. Only Augusta National (82 times for the Masters since Seve Ballesteros (1977-78) Tournament), has held the same event more times than the Swiss venue • With his victory last year, Fitzpatrick became the youngest player to reach four European Tour victories, aged 23 years and nine days, since • In 2010, Miguel Angel Jiménez won his first Omega European Masters Matteo Mannassero won the 2014 BMW PGA Championship aged 20 title at the 22nd attempt. At the time, it was a European Tour record for years and 37 days a player competing in the same event the most number of times before winning it for the first time. -

Thesis, References, and Appendices in .Pdf

Durham E-Theses Cultural Capital and Habitus in Golf Consumption: Embedded Mechanisms of Transference GLENN, JAMES,WILLIAM,EDWARDS How to cite: GLENN, JAMES,WILLIAM,EDWARDS (2020) Cultural Capital and Habitus in Golf Consumption: Embedded Mechanisms of Transference, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13804/ Use policy This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk James William Edwards Glenn Cultural Capital and Habitus in Golf Consumption: Embedded Mechanisms of Transference Abstract This study looks to advance our understanding of the increasingly nuanced cultural capital, subcultural capital, and habitus in consumer research by exploring how individuals transfer dispositions of habitus and embodied forms of capital across field boundaries. Using an ethnographic and autoethnographic approach, the research examines how mechanisms of transference, embedded in the habitus and homogeneity between valorizing field structures, permit individuals to utilize aggregated forms of cultural and subcultural capital sculpted by the field of golf. Through participant observation, interviews, journals, and over two years of exhaustive golf performance, both in the Northeast of England and further abroad, the research illustrates how narratives of soft skills and emotional capital shape the dispositions of individuals acquired, developed, and complemented by significant secondary socialization. This research contributes to the existing consumer research and consumer culture theory by extending understandings and conceptualisations of marketplace cultures, particularly subcultures of sport, and how cultural resources and distinctive practices previously thought to be context- dependent might be transferred.