Thesis, References, and Appendices in .Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 ALPS TOUR QUALIFYING SCHOOL for the 2019 Season

2018 ALPS TOUR QUALIFYING SCHOOL For the 2019 season First Qualifying Stage: 9th & 10th December 2018 Final Qualifying Stage: 13th, 14th & 15th December 2018 1. FORMAT The school will be conducted in two stages of stroke play. FIRST QUALIFYING STAGE: (36 holes scheduled) – Sunday 9th & Monday 10th December 2018 This applies to all applicants except those who have automatically qualified for the Final Stage. First Stage will be played on 9th and 10th December 2018 at the following venue: La Cala Resort « ASIA Course » « AMERICA Course » « EUROPA Course » Urb. La Cala Golf s/n Costa de Mijas – 29649 Malaga SPAIN +34 952 669 033 +34 952 669 023 [email protected] www.lacala.com Malaga (39 km) Malaga (47 km) In the event of a delay in completing the First Stage, applicants are advised that the Tuesday 11th December 2018 may be used as a full playing day in order to complete the competition. Applicants must indicate on the application form their venue preferences in order from 1 to 3. The Alps Tour takes account of each applicant’s venue preference where possible but the primary objective is to balance the number of applicants playing at each venue. In the event of any venue being oversubscribed, priority will initially be determined by the payment date of the entry fee. The first 50 paid up entries received by the Alps Tour for each venue will be allocated to that venue. Thereafter, applicants will be allocated the venue which is highest in their list of preferences and which has availability at the time the application form and payment are received. -

A Dynamic Bayesian Network to Predict the Total Points Scored in National Basketball Association Games Enrique Marcos Alameda-Basora Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 A dynamic Bayesian network to predict the total points scored in national basketball association games Enrique Marcos Alameda-Basora Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Engineering Commons, and the Statistics and Probability Commons Recommended Citation Alameda-Basora, Enrique Marcos, "A dynamic Bayesian network to predict the total points scored in national basketball association games" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16955. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16955 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A dynamic Bayesian network to predict the total points scored in national basketball association games by Enrique M. Alameda-Basora A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Industrial Engineering Program of Study Committee: Sarah Ryan, Major Professor Dan Nettleton Sigurdur Olafsson The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2019 Copyright © Enrique M. Alameda-Basora, 2019. All rights reserved. -

Annual Report

Making a point... with viewpoints. Making a point... with viewpoints. There’s information. It’s like a mirror, simply reflecting what’s there. And then there’s news. Unlike information, news is never one-sided. News has got facets. That’s the difference you discover when you watch news on Zee. It’s like looking through a kaleidoscope. You find perspectives that are unexplored. You see things that are unexpected. You hear voices yet unheard. Because we believe, that we are not merely conduits of information. We are the champions of every single viewpoint. And that makes us the unshakable pillar of democracy. Making a point... with viewpoints. There’s information. It’s like a mirror, simply reflecting what’s there. And then there’s news. Unlike information, news is never one-sided. News has got facets. That’s the difference you discover when you watch news on Zee. It’s like looking through a kaleidoscope. You find perspectives that are unexplored. You see things that are unexpected. You hear voices yet unheard. Because we believe, that we are not merely conduits of information. We are the champions of every single viewpoint. And that makes us the unshakable pillar of democracy. ACROSS THE PAGES CORPORATE OVERVIEW Making a point with viewpoints 01 COVID-19 - Unprecedented Challenges 04 COVID-19 - Unprecedented Response @ Zee Media Network 06 The Edge with ZMCL 08 Zee Media News Network - A Glimpse 10 Empowering Content for Informed Viewpoint 16 Events & Campaigns 19 A Testimonial of Empowering the Viewpoint 22 Financial, Operational and Strategic -

George Coetzee

George Coetzee Representerar Sydafrika (RSA) Född 1986-07-18 Status Proffs Huvudtour European Tour SGT-spelare Nej Aktuellt Ranking 2021 George Coetzee har i år spelat 14 tävlingar. Han har klarat 8 kval. På dessa 14 starter har det blivit 1 topp-10-placeringar. Som bäst har George Coetzee en 10-plats i Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors. Han har i år en snittscore om 70,48 efter att ha slagit 3101 slag på 44 ronder. George Coetzee har på de senaste starterna placeringarna 26-MC-MC-27-75 varav senaste starten var BMW PGA Championship. Han har i år som bästa score noterat 64 (-8) i Dimension Data Pro-Am på Fancourt Golf Estate. 20 av årets 44 ronder har varit under par. Vid 15 tillfällen har det noterats scorer på under 70 slag men också vid 1 tillfällen minst 75 slag. George Coetzee har klarat kvalet i de 2 senaste tävlingarna. Kvalsviten i år löper från DS Automobiles Italian Open (vecka 35/2021). Årets tävlingar Plac Tävling Plac Tävling Plac Tävling 75 BMW PGA Championship MC Dubai Duty Free Irish Open MC Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Wentworth Golf Club, European Tour Mount Juliet Estate, European Tour Education City GC, European Tour 27 DS Automobiles Italian Open MC PGA Championship 10 Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors Marco Simone GC, European Tour Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, PGA Tour Royal Greens G&CC, European Tour MC Omega European Masters 14 Dimension Data Pro-Am 60 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Crans-sur-Sierre GC, European Tour Fancourt Golf Estate, European Challenge Tour -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y

. OP U.S EN SHINNECOCK HILLS TH 118TH U.S. OPEN PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y. — June 14-17, 2018 conducted by the 2018 U.S. OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List SHOTA AKIYOSHI Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying for the 118th U.S. Open Championship, with their exemption categories Shota Akiyoshi is 183 in this week’s Official World Golf Ranking listed. Birth Date: July 22, 1990 Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kumamoto, Japan Kiradech Aphibarnrat 13 Marc Leishman 12, 13 Age: 27 Ht.: 5’7 Wt.: 190 Daniel Berger 12, 13 Alexander Levy 13 Home: Kumamoto, Japan Rafael Cabrera Bello 13 Hao Tong Li 13 Patrick Cantlay 12, 13 Luke List 13 Turned Professional: 2009 Paul Casey 12, 13 Hideki Matsuyama 11, 12, 13 Japan Tour Victories: 1 -2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Kevin Chappell 12, 13 Graeme McDowell 1 Open. Jason Day 7, 8, 12, 13 Rory McIlroy 1, 6, 7, 13 Bryson DeChambeau 13 Phil Mickelson 6, 13 Player Notes: ELIGIBILITY: He shot 134 at Japan Memorial Golf Jason Dufner 7, 12, 13 Francesco Molinari 9, 13 Harry Ellis (a) 3 Trey Mullinax 11 Club in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, to earn one of three spots. Ernie Els 15 Alex Noren 13 Shota Akiyoshi started playing golf at the age of 10 years old. Tony Finau 12, 13 Louis Oosthuizen 13 Turned professional in January, 2009. Ross Fisher 13 Matt Parziale (a) 2 Matthew Fitzpatrick 13 Pat Perez 12, 13 Just secured his first Japan Golf Tour win with a one-shot victory Tommy Fleetwood 11, 13 Kenny Perry 10 at the 2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Open. -

2020-21 Men's Golf

U NIVERSITY OF I LLINOIS 2020-21 MEN’S GOLF TABLE OF CONTENTS Head Coach Mike Small ����������������������������������������2-7 Assistant Coach Justin Bardgett / Director of Operations Jackie Szymoniak���8 Michael Feagles �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9-10 Giovanni Tadiotto . .11-12 Brendan O’Reilly � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Luke Armbrust� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �14 Adrien Dumont de Chassart ��������������������������������������15 Tommy Kuhl ��������������������������������������������������16 Jerrry Ji ������������������������������������������������������17 Nico Lang ����������������������������������������������������18 Piercen Hunt ��������������������������������������������������19 Olympia Fields Country Club Fighting Illini Invitational �����������������20 2019-20 Review . 21-22 2019-20 Results/Statistics������������������������������������23-27 Team Records ����������������������������������������������28-29 Individual Records . 30-32 Big Ten Championships Results �����������������������������������33 2020-21 ILLINOIS MEN’S GOLF ROSTER NCAA Regional & NCAA Championships Results�����������������������34 Name Year Hometown / Previous School Individual Honors �������������������������������������������34-36 Luke Armbrust Jr� Wheaton, Illinois/St� Francis All-Time Letterwinners ���������������������������������������37-38 Adrien Dumont -

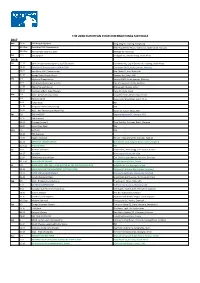

2017 2018 the 2018 European Tour International Schedule

THE 2018 EUROPEAN TOUR INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE 2017 Nov 23-26 UBS Hong Kong Open Hong Kong GC, Fanling, Hong Kong 30-3 Dec Australian PGA Championship RACV Royal Pines Resort, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia 30-3 Dec AfrAsia Bank Mauritius Open Heritage GC, Mauritius Dec 7-10 Joburg Open Randpark GC, Johannesburg, South Africa 2018 Jan 11-14 BMW SA Open hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni Glendower GC, City of Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, South Africa 12-14 EURASIA CUP presented by DRB-HICOM Glenmarie G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 18-21 Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship Abu Dhabi GC, Abu Dhabi, UAE 25-28 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Emirates GC, Dubai, UAE Feb 1-4 Maybank Championship Saujana G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 8-11 ISPS Handa World Super 6 Perth Lake Karrinyup CC, Perth, Australia 15-18 NBO Oman Golf Classic Almouj Golf, Muscat, Oman 22-25 Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Doha GC, Doha, Qatar Mar 1-4 WGC - Mexico Championship Chapultepec GC, Mexico City, Mexico 1-4 Tshwane Open Pretoria CC, Waterkloof, South Africa 8-11 Indian Open TBA 15-18 Philippines Golf Championship TBA 21-25 WGC - Dell Technologies Match Play Austin CC, Austin, Texas, USA Apr 5-8 THE MASTERS Augusta National GC, Georgia, USA 12-15 TBA (Europe) 19-22 Trophee Hassan II Royal Golf Dar Es Salam, Rabat, Morocco 26-29 Volvo China Open TBA May 5-6 GolfSixes TBA 10-13 TBA (Europe) 17-20 Belgian Knockout Rinkven International GC, Antwerp, Belgium 24-27 BMW PGA CHAMPIONSHIP Wentworth Club, Virginia Water, Surrey, England 31-3 Jun ITALIAN OPEN TBA Jun 7-10 Austrian Golf Open Diamond CC, Atzenbrugg, near Vienna, Austria 14-17 US OPEN Shinnecock Hills GC, NY, USA 21-24 BMW International Open Golf Club Gut Laerchenhof, Pulheim, Germany 28-1 Jul HNA OPEN DE FRANCE Le Golf National, Paris, France Jul 5-8 DUBAI DUTY FREE IRISH OPEN HOSTED BY THE RORY FOUNDATION Ballyliffin GC, Co. -

Reviewer Evaluation

Dear Dr. Dimyati, This is the first review, as below. I also ask Prof. Suherman about his opinion. Later, you will be asked for sending me your corrected manuscript - the re-submission. Yet, not now. Best Regards, Wojciech J. Cynarski www.imcjournal.com I kindly ask Prof. ... to evaluate the enclosed work – entitled: … Exploring the Psychological Skills of Indonesian Pencak Silat Athletes in the 18thAsian Games. Reviewer Evaluation Topic of work : Sport psychology in martial art Pencak Silat 1/ Is the content consistent with the topic of work? Partially. 2/ Evaluation of the layout of work, its structure, coherence, order of chapters, theses, completeness, etc. In general, the work is not finished. There is no description of the results and discussion. 3/ Detailed evaluation of work No work purpose. Methods do not sufficiently describe the essence of research. The results are not over. Partly in the section Results a literature review is presented. Not enough described the results of the tables. The discussion does not concern the content of the article. The conclusions do not reflect the results of the work. 4/ Other remarks The group of athletes is not analyzed by typological characteristics. For example, in terms of motivation, anxiety, or concentration. 5/ To what extent does the work treat the problem in a new way? There is no novelty in the work. Pencak Silat Athletes Research is not new. Need an idea that is not. 6/ Is the literature / resources relevant to the study? In general, yes. 7/ Evaluation of writing style (language, grammar, technique, contents, referencing)? The style and grammar of the article is generally satisfactory. -

Seme 2018 – Conference Schedule: Day 1 Updated 4.5 #Seme18

SEME 2018 – CONFERENCE SCHEDULE: DAY 1 UPDATED 4.5 #SEME18 @ American University, Spring Valley Building, Room 602 FRIDAY, APRIL 6 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM Registration and Breakfast 8:50 AM – 9:00 AM Welcome and Introduction Matt Winkler – SEME Executive Director; American University, Director, Online M.S. in Sports Analytics Jimmy Lynn – Co-Founder, Kiswe Mobile; Georgetown University 9:05 AM – 9:40 AM Keynote Presentation: Ahmad Nassar – President, NFL Players Inc. 9:50 AM – 10:40 AM State of the Industry Trends and Outlook for 2018 in Sports Joe Briggs – Counsel, NFL Players Association (NFLPA) John Ourand – Media Reporter, Sports Business Journal Jennifer Matthews – Sr. Director of Marketing & Strategy, Monumental Sports Network Matthew Stanton – Vice President, Global Public Policy, Under Armour Moderator: Matt Winkler – SEME Executive Director; American University 10:50:AM – 11:40 AM Leadership & Competition in a Global Sports Environment Brian Burke – Analytics Specialist, Stats & Information Group, ESPN Walker Fletcher – Managing Director Americas, F.C.INTERNAZIONALE MILANO Kirsten Seckler – Chief Marketing Officer, Special Olympics International Moderator: Steve Goodman – Chief Relationship Officer, Arjuna Solutions 11:50 AM – 12:40 PM Industry Executive Interactive Breakout Lunch Exploration Lunch @ Room 619 Ryan Bartholomew – Director of Marketing & Ticketing, NCAA Military Bowl presented by Northrop Grumman Sponsored by Steve Beck – President & Executive Director, NCAA Military Bowl presented by Northrop Grumman Chase Cates – Sports Marketing Strategist, ESPN/Redskins Radio Marc Goldman – Sponsorship & Marketing Manager, The Marine Coprs Marathon Tony Korson – Chief Executive Officer, KOA Sports Luke Mohamed – Director of Corporate Partnerships, DC United (MLS) Rachel Northridge – Client Services Manager, Monumental Sports & Entertainment Ben Richardson – Coordinator, Corporate Partnerships, Team Services LLC Joe Schoenbauer – Director, U.S. -

2017-2018 Player Handbook & Tournament Regulations

2017-2018 PLAYER HANDBOOK & TOURNAMENT REGULATIONS PGA TOUR 112 PGA TOUR Boulevard Ponte Vedra Beach, FL 32082 Telephone: 904/285-3700 Dear PGA TOUR members, Welcome to the PGA TOUR. This directory was compiled to assist you in your preparation for a season on the PGA TOUR. The Player Handbook includes a 2017-2018 tournament schedule and covers such top- ics as special event eligibility and special awards. The Tournament Regulations are the guide to specific rules pertaining to PGA TOUR play. We have incorporated changes made to the Tournament Regulations since last season into this season’s book. In addition, the index provides quick reference. These Regulations are the final authority on the operations and policies of the PGA TOUR. I encourage every member to become familiar with these rules. Best wishes for a successful 2017-2018 season! Jay Monahan Commissioner PGA TOUR SIGNIFICANT CHANGES FOR THE 2017-2018 SEASON • Elimination of the Official Money List Leader exemption beginning with the leader of the 2016-2017 season. • The Top 125 Official Money List category has been eliminated. • Introduction of PGA TOUR Integrity program which among other things prohibits players from betting on professional golf. • Amendments to the Pace of Play Policy. • Amendments to the Player Endorsement Policy to exclude sponsorships by FedEx competitors. • Addition of an official pro-am format whereby one professional plays the first nine holes and a second professional plays the second nine holes. • Changes to the One New Event Played Per Season Requirement to exclude any first-year official money event. • Changes to the Ryder Cup points structure. -

EXPLOSIVE POWER in BASKETBALL PLAYERS UDC 796.015.332 Nikola Aksović, Miodrag Kocić, Dragana Berić, Saša Bubanj

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Physical Education and Sport, Vol. 18, No 1, 2020, pp. 119 - 134 https://doi.org/10.22190/FUPES200119011A Review article EXPLOSIVE POWER IN BASKETBALL PLAYERS UDC 796.015.332 Nikola Aksović, Miodrag Kocić, Dragana Berić, Saša Bubanj Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Niš, Niš, Serbia Abstract. Explosive power in basketball is manifested through various variants of jumps, starting acceleration, sudden changes in direction, deceleration, sudden stops and passing. The aim of this research is to identify and sum up the relevant literature published in the period from 2000 to 2019, focusing on the explosive power of basketball players, and to explain relations between training programs and explosive power development. The results confirmed that explosive power is a significant characteristic of professional basketball players and one of the most important factors for achieving top results. The results show that in spite of the inborn coefficient, the development of explosive power can be realized through planned, rational and well- organized training. A positive correlation was determined between explosive power and running at short distances, jumps and throwing, as well as between explosive power and lean body mass in basketball players of different ages. It is necessary to give greater attention to the training of explosive power, because it is an effective means that contributes to the efficiency of the basketball player. Key words: Basketball, Explosive strength, Vertical Jump, Speed, Agility INTRODUCTION Basketball is a high-intensity team sport with alternative phrases of high load, and success in basketball requires technical, tactical and physical preparation. In basketball, explosive power is manifested through various variants of jumps, starting acceleration, sudden changes in direction of movement, deceleration, sudden stops and passing. -

Martin Kaymer

Martin Kaymer Representerar Tyskland (GER) Född Status Proffs Huvudtour European Tour SGT-spelare Nej Aktuellt Ranking 2021 Martin Kaymer har i år spelat 16 tävlingar. Han har klarat 8 kval. På dessa 16 starter har det blivit 2 topp-10-placeringar. Som bäst har Martin Kaymer en 2-plats i BMW International Open. Han har i år en snittscore om 71,02 efter att ha slagit 3409 slag på 48 ronder. Martin Kaymer har på de senaste starterna placeringarna MC-MC-18-MC-25 varav senaste starten var BMW PGA Championship. Han har i år som bästa score noterat 64 (-8) i BMW International Open på Golfclub München Eichenried. 24 av årets 48 ronder har varit under par. Vid 15 tillfällen har det noterats scorer på under 70 slag men också vid 2 tillfällen minst 75 slag. Årets tävlingar Plac Tävling Plac Tävling Plac Tävling 25 BMW PGA Championship 2 BMW International Open MC The Honda Classic Wentworth Golf Club, European Tour Golfclub München Eichenried, European Tour PGA National (Champion) , PGA Tour MC DS Automobiles Italian Open 26 U.S. Open 18 Saudi International powered by SoftBank Investment Advisors Marco Simone GC, European Tour Torrey Pines (South), PGA Tour Royal Greens G&CC, European Tour 18 Omega European Masters MC Porsche European Open 44 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Crans-sur-Sierre GC, European Tour Green Eagle Golf Courses, European Tour Emirates GC, European Tour MC THE 149TH OPEN MC PGA Championship MC Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship presented by EGA Royal St George’s GC, European Tour Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, PGA Tour Abu Dhabi GC, European Tour MC abrdn Scottish Open MC Betfred British Masters hosted by Danny Willet The Renaissance Club, European Tour The Belfry, European Tour 41 Dubai Duty Free Irish Open 3 Austrian Open Mount Juliet Estate, European Tour Diamond CC, European Tour Karriären Totala prispengar 1997-2021 Martin Kaymer har följande facit så här långt i karriären: (officiella prispengar på SGT och världstourerna) Summa Största Snitt per 20 segrar på 404 tävlingar.