Under Pressure Contemporary Prints from the Collections of Jordan D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vija Celmins Free

FREE VIJA CELMINS PDF Vija Celmins,Robert Gober,Lane Relyea,Briony Fer | 160 pages | 01 Dec 2004 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9780714842646 | English | London, United Kingdom Vija Celmins | artnet This has never been a problem for Celmins. Her art has awed critics and found buyers since she began showing it, in the early nineteen-sixties, and her paintings now bring between three and five million on the primary market. Still, she produces relatively little work and vigorously resists all forms of self-promotion. From the late sixties until quite recently, her subject matter has been limited to a few recurrent motifs—oceans, deserts, night skies, spiderwebs, antique writing slates—which she explores, patiently Vija Celmins obsessively, in drawings, oil paintings, prints, and sculptural objects that are unlike those of any other artist. She has erased the line between figuration and abstraction. Composition, bright color, narrative, and the human figure have no place in her work, which, at its best, conveys a timeless, impersonal, and rather cold beauty that can be inexplicably moving. When I walked through the exhibition with her in December, she was not happy about the lighting in the first two galleries, where her early paintings were hung. A technician went off to adjust it. One gallery was dedicated to the paintings that she considers her first mature works, all done in —deadpan, Vija Celmins still-lifes of functional objects in the studio she had at the time Vija Celmins Los Angeles. Some Vija Celmins these, the heater especially, with its glowing red coil, had a somewhat ominous look. -

Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey. Lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. EDUCATION 1966 Art and Design, Parsons School of Design, New York 1965 Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021-2023 Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York] [forthcoming] [catalogue forthcoming] 2019 Barbara Kruger: Forever, Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul [catalogue] Barbara Kruger - Kaiserringträgerin der Stadt Goslar, Mönchehaus Museum Goslar, Goslar, Germany 2018 Barbara Kruger: 1978, Mary Boone Gallery, New York 2017 Barbara Kruger: FOREVER, Sprüth Magers, Berlin Barbara Kruger: Gluttony, Museet for Religiøs Kunst, Lemvig, Denmark Barbara Kruger: Public Service Announcements, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2016 Barbara Kruger: Empatía, Metro Bellas Artes, Mexico City In the Tower: Barbara Kruger, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 2015 Barbara Kruger: Early Works, Skarstedt Gallery, London 2014 Barbara Kruger, Modern Art Oxford, England [catalogue] 2013 Barbara Kruger: Believe and Doubt, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria [catalogue] 2012-2014 Barbara Kruger: Belief + Doubt, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC 2012 Barbara Kruger: Questions, Arbeiterkammer Wien, Vienna 2011 Edition 46 - Barbara Kruger, Pinakothek -

Visual Narratives of Heterosexual Female Sexuality.Docx

Running Head: Visual Narratives of Heterosexual Female Sexuality Visual Narratives of Heterosexual Female Sexuality By Angie Wallace Masters in Interdisciplinary Studies Southern Oregon University 2018 Visual Narratives of Heterosexual Female Sexuality 2 Table of Contents Abstract Page 3 Introduction Page 4 Research Questions Page 6 Literature Review Page 7 Methods Page 22 IRB Page 25 Results Page 25 Figures 1, 2, and 3 Page 30 - 31 Discussion Page 31 Research based Art Piece Page 37 Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7 Page 41 - 42 References Page 43 Visual Narratives of Heterosexual Female Sexuality 3 Abstract This paper explores the social construction of heterosexual female sexuality through visual social narratives in the form of advertisements and artistic photographs. The purpose of this study it to produce an art piece based on my findings. The problems I encountered during my research include my own bias and limited subjects. Since, I am a woman who identifies as heterosexual I have my own preconceived ideas along with personal experiences. In addition, the limited data set provides its own drawbacks. If I were to broaden my scope, the data may or may not have revealed other themes. That being said, for my purposes the themes that have emerged include the following; (1) the male gaze, (2) gender performance, (3) body as a commodity, and (4) sexual harassment. Through the process of visual ethnography and methodology, my design study is to analyze these images as a heterosexual female and combine this analysis with the literature. During this process, I have concluded that heterosexual female sexuality is contingent on how we recognize and interpret visual culture. -

Art in the Twenty-First Century Screening Guide: Season

art:21 ART IN2 THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE: SEASON TWO SEASON TWO GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE ABOUT ART21, INC. This screening guide is designed to help you plan an event Art21, Inc. is a non-profit contemporary art organization serving using Season Two of Art in the Twenty-First Century. This guide students, teachers, and the general public. Art21’s mission is to includes a detailed episode synopsis, artist biographies, discussion increase knowledge of contemporary art, ignite discussion, and inspire questions, group activities, and links to additional resources online. creative thinking by using diverse media to present contemporary artists at work and in their own words. ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS Public screenings of the Art:21 series engage new audiences and Art21 introduces broad public audiences to a diverse range of deepen their appreciation and understanding of contemporary art contemporary visual artists working in the United States today and and ideas. Organizations and individuals are welcome to host their to the art they are producing now. By making contemporary art more own Art21 events year-round. Some sites plan their programs for accessible, Art21 affords people the opportunity to discover their broad public audiences, while others tailor their events for particular own innate abilities to understand contemporary art and to explore groups such as teachers, museum docents, youth groups, or scholars. possibilities for new viewpoints and self-expression. Art21 strongly encourages partners to incorporate interactive or participatory components into their screenings, such as question- The ongoing goals of Art21 are to enlarge the definitions and and-answer sessions, panel discussions, brown bag lunches, guest comprehension of contemporary art, to offer the public a speakers, or hands-on art-making activities. -

Download Artist's CV

Vija Celmins 1938 Born in Riga, Latvia 1962 Graduated from John Herron School of Art, Indianapolis, B.F.A. 1962 Graduated from University of California, Los Angeles, M.F.A. Selected One-Person Exhibitions 2020 Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, The Met Breuer, New York, NY 2019 Ocean Prints, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York 2018 Matthew Marks Gallery, Los Angeles ARTIST ROOMS: Vija Celmins, The New Art Gallery Walsall, United Kingdom To Fix the Image in Memory, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Traveling to Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; and The Met Breuer, New York (catalogue) 2017 Matthew Marks Gallery, New York (catalogue) Selected Prints, The Drawing Room, East Hampton, NY 2015 Secession, Vienna (catalogue) Selected Prints, Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl Project Space, New York National Centre for Craft and Design, Sleaford, United Kingdom 2014 Intense Realism, Saint Louis Art Museum Double Reality, Latvian National Art Museum, Riga (catalogue) 2012 Artist Rooms: Vija Celmins, Tate Britain, London. Traveled to National Centre for Craft & Design, Sleaford, United Kingdom 2011 Prints and Works on Paper, Senior and Shopmaker Gallery, New York Desert, Sea, and Stars, Ludwig Museum, Cologne. Traveled to Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark (catalogue) 2010 New Paintings, Objects, and Prints, McKee Gallery, New York Television and Disaster, 1964–1966, Menil Collection, Houston. Traveled to Los Angeles County Museum of Art (catalogue) 2006 Drawings, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Traveled to Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (catalogue) 2003 Prints, Herron School of Art, Indianapolis The Paradise [15] , Douglas Hyde Gallery, Trinity College, Dublin 2002 Works from The Edward R. -

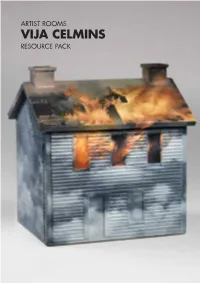

Vija Celmins Resource Pack About This Resource Contents

ARTIST ROOMS VIJA CELMINS RESOURCE PACK ABOUT THIS RESOURCE CONTENTS Vija Celmins is one of the most widely acclaimed What is ARTIST ROOMS? 03 artists working today, with a career spanning six decades from the early 1960s. The ARTIST ROOMS Vija Celmins 04 collection currently holds thirty-four works on paper by Celmins dating from 1974 until 2010. It includes 1. FOUND IMAGES 06 unique graphite, charcoal and eraser drawings such as Untitled (Galaxy-Desert) 1974 and Web #1 1999, 2. NATURAL WORLD 09 as well as prints which employ intaglio, lithographic and relief processes. 3. IMAGE AND SCALE 11 The ARTIST ROOMS collection of works by Vija Celmins is one of the largest museum collections in 4. PROCESS AND MATERIALS 13 the world. Other significant works are held in the USA by LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of 5. MEMORY 15 Art), MoMA (the Museum of Modern Art, New York), the Whitney Museum (New York), SFMoMA (San 6. TIME 17 Francisco Museum of Modern Art), MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) and Modern Art Summary 20 Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Further reading 21 This resource is designed to aid teachers and students using the ARTIST ROOMS Vija Celmins collection. Glossary 22 The resource focuses on specific works and themes and suggests areas of discussion, activities and links to other artists in the collection. For schools, the work of Vija Celmins presents a good opportunity to explore cross-curricula learning. The themes in Celmins work can be linked to curricula areas such as English, expressive arts, health and wellbeing, social studies, citizenship and science. -

Brice Marden Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Brice Marden Bibliography Selected Monographs and Solo Exhibition Catalogues: 2019 Brice Marden: Workbook. New York: Gagosian. 2018 Rales, Emily Wei, Ali Nemerov, and Suzanne Hudson. Brice Marden. Potomac and New York: Glenstone Museum and D.A.P. 2017 Hills, Paul, Noah Dillon, Gary Hume, Tim Marlow and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. London: Gagosian. 2016 Connors, Matt and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2015 Brice Marden: Notebook Sept. 1964–Sept.1967. New York: Karma. Brice Marden: Notebook Feb. 1968–. New York: Karma. 2013 Brice Marden: Book of Images, 1970. New York: Karma. Costello, Eileen. Brice Marden. New York: Phaidon. Galvez, Paul. Brice Marden: Graphite Drawings. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Weiss, Jeffrey, et al. Brice Marden: Red Yellow Blue. New York: Gagosian Gallery. 2012 Anfam, David. Brice Marden: Ru Ware, Marbles, Polke. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Brown, Robert. Brice Marden. Zürich: Thomas Ammann Fine Art. 2010 Weiss, Jeffrey. Brice Marden: Letters. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2008 Dannenberger, Hanne and Jörg Daur. Brice Marden – Jawlensky-Preisträger: Retrospektive der Druckgraphik. Wiesbaden: Museum Wiesbaden. Ehrenworth, Andrew, and Sonalea Shukri. Brice Marden: Prints. New York: Susan Sheehan Gallery. 2007 Müller, Christian. Brice Marden: Werke auf Papier. Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel. 2006 Garrels, Gary, Brenda Richardson, and Richard Shiff. Plane Image: A Brice Marden Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art. Liebmann, Lisa. Brice Marden: Paintings on Marble. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2003 Keller, Eva, and Regula Malin. Brice Marden. Zürich : Daros Services AG and Scalo. 2002 Duncan, Michael. Brice Marden at Gemini. -

Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964-66

Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964-66 A rare look at a little-known facet of artist’s oeuvre On view at the Menil Collection November 19, 2010 - February 20, 2011 Exhibition Preview: Thursday, November 18, 7:00-9:00 P.M. CONVERSATION WITH THE ARTIST: VIJA CELMINS AND CURATORS APPEAR IN A PUBLIC PROGRAM AT THE MENIL 7:00 P.M., FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 19th Houston, October 27, 2010 – Throughout much of her career, Vija Celmins has been known for her captivating paintings and drawings of starry night skies, fragile spider webs, and barren desert floors – quiet, expansive worlds meticulously executed in gradations of black and grey. As a young artist in Los Angeles during the early 1960s, however, Celmins’s work was marked by a distinctly different tone, one influenced by the violence of the era and the mass media that represented it. Realistically rendering images from newspapers, magazines, and television, Celmins filled her canvases with smoking handguns, crashing warplanes, and other images of disaster and violence. Co-organized by the Menil Collection and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964-66 explores this essential yet often overlooked period of the artist’s work. While recent surveys at the Centre Pompidou and the Metropolitan Museum of Art focused on Celmins’s drawings and prints, this exhibition is the first to concentrate on a specific time frame and subject matter within the artist’s oeuvre. With nearly twenty paintings and three sculptures, all from a brief three-year period, Television and Disaster uncovers the technical and thematic groundwork from which Celmins would build her international career. -

Moma Archives Oral History: V. Celmins – Page 1 of 62 THE

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: VIJA CELMINS, ARTIST INTERVIEWER: BETSY SUSSLER, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, BOMB MAGAZINE LOCATION: The Museum of Modern Art DATE: October 18, 2011 BEGIN AUDIO FILE Celmins_T04 duration 25:52 BS: We’re in the Drawing Center at The Museum of Modern Art at 11 West 53rd Street in New York City on October 18th, 2011, with, I’m Betsy Sussler, Editor-in-Chief of Bomb Magazine, and we’ll be interviewing, or doing an oral history, I should say, with Vija Celmins, the artist. And Vija, I just want to start by saying yes, that this is an oral history, so what I’m going to be doing, and at any point if you don’t want to discuss whatever I bring up, just say, “Let’s move on.” I’m going to be moving in and out of a narrative that’s basically a linear narrative from the time you were born up until now. So we’ll be moving in and out of your life, into the art, and from the art, back into your life. And at any point, if you have any anecdotal material that you want to add, just go, and I’ll shut up, and you can come on in, because it’s your oral history. So I want to start, of course, as we all start, with Riga, with Latvia. You were born in 1938. In your first years of your childhood, there were two occupations, the Russians came in in 1940, I believe, and then the Germans came in. -

Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Katarína Belejová Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Bc. Katarína Belejová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr., for his encouragement, patience and inspirational remarks. I would also like to thank my family for their support. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Postmodern Art, Conceptual Art and Social Criticism .............................................. 7 1.1 Social Criticism as a Part of Postmodernity ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Postmodernism, Conceptual Art and Promotion of a Thought .................................. 9 1.2. Importance of Subversion and Parody ........................................................................... 12 1.3 Conceptual Art and Its Audience ...................................................................................... 16 2. American context ..................................................................................................... 21 2.1 The 1980s in the USA ......................................................................................................... -

Barbara Kruger Believe + Doubt 19|10|2013- 12|01|2014

KUB 2013.04 | Press release Barbara Kruger Believe + Doubt 19|10|2013- 12|01|2014 Curators of the exhibition Yilmaz Dziewior and Rudolf Sagmeister Press Conference Thursday, October 17, 2013, 12 noon The exhibition is opened for the press at 11 a.m. Opening Friday, October 18, 2013, 7 p.m. Page 1 | 24 Few artists have succeeded in treating the ambivalent ef- fects of the mass media and their powers of persuasion in impressive works of art so cogently and variously as Bar- bara Kruger has done for more than four decades now. So it is no surprise that she is represented in major museum collections worldwide and enjoys broad public attention through exhibitions at renowned institutions. She has had large-scale solo exhibitions, for example, at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. In addition, she participated in documenta 7 (1982) and documenta 8 (1987) in Kassel, and she received the »Golden Lion« at the 51 st Venice Biennale 2005 for her life’s work. It is all the more surpris- ing then that the exhibition covering three floors of the Kunsthaus Bregenz is her first major institutional solo show in Austria. Not that Barbara Kruger is a newcomer to Bregenz. In summer 2011 she participated in the Kunsthaus Bregenz solidarity action for Ai Weiwei by designing a poster con- sisting of white lettering on a red ground asking »Why Weiwei«—and adding, in smaller lettering below, her familiar formula: »Belief + Doubt = Sanity.« Before this, in the same year, for the KUB group exhibition That’s the way we do it , she produced an almost 20 meter long by 4 meter high digital print that addressed the issues around so called »intellectual property« and the distributional powers of the internet. -

MOCA Masks (#Mocamasks) Are a Collection of Limited-Production, Artist-Designed Face Masks for Kids and Adults

MOCA Masks (#MOCAmasks) are a collection of limited-production, artist-designed face masks for kids and adults. Each purchase directly supports The Museum of Contemporary Art. MOCA Masks are designed by Virgil Abloh, Mark Grotjahn, Alex Israel, Barbara Kruger, Yoko Ono, Catherine Opie, Pipilotti Rist, Hank Willis Thomas, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts. Each mask is handmade in Los Angeles, California, and is carefully crafted to combine art and safety. We remain committed to making art accessible and encouraging the urgency of contemporary expression. #MOCAmasks @moca @mocastores moca.org/masks “Still Speaks Loudly” VIRGIL ABLOH 2020 Virgil Abloh (b. 1980, Rockford, Illinois) is an artist, architect, engineer, creative director, and fashion designer. After earning a degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Wisconsin- Madison, he completed a Master's degree in Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology. It was here that he learned not only about design principles but also crafted the principles of his art practice. He studied a curriculum devised by Mies van der Rohe, on a campus he designed. Currently, he is the Chief Creative Director and founder of Off-White™ and the Artistic Director of Menswear at Louis Vuitton. Untitled (Creamsicle Covid 19) MARK GROTJAHN 2020 Mark Grotjahn (b. 1968, Pasadena, California) combines gesture and geometry with abstraction and figuration in visually dynamic paintings, sculptures, and works on paper. Each of his series reflects a range of art-historical influences and unfolds in almost obsessive permutations. He received a BFA from the University of Colorado at Boulder and an MFA from the University of California at Berkeley.