“Thailand-Plus-One” Business Model -A New Fragmentation in East Asia By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investing in 'China Plus One' Economies

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2015 Investing In ‘China Plus One’ Economies By Robert W. Wood and Huy C. Luu BITs are meant to encourage investments between the signatory countries, and to protect the investment interests of the nvestors are increasingly taking note of emerging Asian foreign investor. A BIT generally includes clauses relating to national economies. Many multinational companies adopt a “China-plus- treatment, which states that a foreign investor must be treated fairly, in I one” strategy to supplement their investments in China. U.S. the same manner as a domestic investor. A BIT also includes a clause investors should properly structure their transactions from a tax limiting expropriation of the investment by the foreign government. perspective in these emerging Asian economies. The U.S. has some BITs, but very few with Asian jurisdictions. Tax treaties often play a critical role in cross-border Thus, if a U.S. investor plans to invest directly into a region where no transactions. Investors want to receive profits in a tax-efficient manner BIT has been concluded (for example, Southeast Asia), there is no without have too much cash trapped in the foreign jurisdiction. guarantee that its investments will be protected. Example: A U.S. investor has investments in Indonesia. BIT Shopping? Distribution of dividends to a non-resident is subject to a withholding It may be beneficial to invest through another entity in a tax rate of 20 percent in Indonesia. Thus, if the dividend payment is jurisdiction that has concluded a BIT with the host country. It is a kind $100, the Indonesian entity must withhold $20 prior to making the net of treaty shopping. -

East Asia Forum Quarterly

EASTASIAFORUM ECONOMICS, POLITICS AND PUBLIC POLICY IN EAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Vol.13 No.2 April–June 2021 $9.50 Quarterly Reinventing global trade Inu Manak Agenda to save the WTO David Dollar Asia’s new foreign investment landscape Homi Kharas and Meagan Dooley The digital transformation Deborah Elms Managing digital trade ... and more ASIAN REVIEW: Angie Baecker and Yucong Hao on boys’ love fan labour CONTENTS EASTASIAFORUM 3 INU MANAK Quarterly Agenda to save the WTO 6 BILAHARI KAUSIKAN ISSN 1837-5081 (print) ISSN 1837-509X (online) Can Asia reinvent global trade? From the Editor’s desk 8 MELY CABALLERO-ANTHONY Towards a multipolar order For long, trade hovered confidently over the Asia Pacific region as its vital post-pandemic growth engine. As average tariffs fell from 17 per cent in 1989 to 5.3 per cent 10 CARLOS KURIYAMA in 2018, regional trade multiplied—faster than the rest of the world—along The international economics with jobs and incomes. Increasing integration even helped the region to of self-harm bounce back from shocks as severe as the 2008–09 global financial crisis. 12 DAVID DOLLAR Escalation of geopolitical tensions seems to have unsettled trade from Clear skies over Asia’s new foreign its perch. As rivalries heightened and criticism of globalisation grew in investment landscape recent years, the multilateral trading system on which Asia’s prosperity and 14 HOMI KHARAS, MEAGAN DOOLEY security had been based was challenged and the WTO’s relevance called The digital transformation of East Asian into question. trade It took a global pandemic to shift the narrative. -

“Made in China” in Deglobalisation

For professional clients only 2 September 2020 Research & Strategy Insights Preserving “Made in China” in deglobalisation Locking in supply chains requires continued reforms and opening up Aidan Yao, Shirley Shen, Senior Economist Economist (Non-China Asia) Macro Research & Core Investments Macro Research – Core Investments Key points China riding high on globalisation • After decades of rapid growth, the progress of The powerful rise of globalisation has been one of the globalisation has slowed since the global financial crisis, defining economic developments of our time. By spreading with its fate further complicated by rising protectionism, production across multiple countries connected via trade and political interference and the COVID-19 outbreak. integrated supply chains, the global economy has achieved momentous efficiency gains and created tremendous values • As the biggest beneficiary, China stands to lose the most in for those involved in the process. As the tissue that connects the event of deglobalisation. So far, however, evidence of “economic organs”, international trade has experienced a disruptions has been scant, with some indicators showing boom since the 1980s. Combined export and import values that China’s market share in trade and manufacturing has surged from 35% of the world’s GDP to over 60% just before in fact risen despite the trade war and pandemic. the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC). Exhibit 1 shows that such stellar growth would not have been possible • This is not to say that China is immune from any supply without the propagation of the multi-country production chain shifts. Some low-margin businesses have already systems that significantly lifted foreign contributions in exited the country in light of rising costs. -

China's March on the 21St Century

China’s March on the 21st Century A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group Kurt M. Campbell, Editor Willow Darsie, Editor u Co-Chairmen Joseph S. Nye, Jr. Brent Scowcroft To obtain additional copies of this report, please contact: The Aspen Institute Fulfillment Office P.O. Box 222 109 Houghton Lab Lane Queenstown, Maryland 21658 Phone: (410) 820-5338 Fax: (410) 827-9174 E-mail: [email protected] For all other inquiries, please contact: The Aspen Institute Aspen Strategy Group Suite 700 One Dupont Circle, NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 736-5800 Fax: (202) 467-0790 Copyright © 2007 The Aspen Institute Published in the United States of America 2007 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-471-8 Inv No.: 07-007 CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v DISCUSSANTS AND GUEST EXPERTS . 1 WORKSHOP AGENDA. 5 SCENE SETTER AND DISCUSSION GUIDE Kurt M. Campbell . 13 THE CHINESE ECONOMY:MAKING STRIDES,GOING GLOBAL Dominic Barton and Jonathan Woetzel Dragon at the Crossroads: The Future of China’s Economy . 25 Lael Brainard Adjusting to China’s Rise . 37 ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT, AND OTHER TRANSNATIONAL CHALLENGES John Deutch, Peter Ogden, and John Podesta China’s Energy Challenge . 53 Margaret A. Hamburg Public Health and China: Emerging Disease and Challenges to Health . 61 OF SOFT POWER AND CHINA’S PEACEFUL RISE Zha Jianying Popular Culture in China Today . 77 Wang Jisi What China Needs in the World and from the United States. 85 STRATEGIC COMPETITION,REGIONAL REACTIONS, AND GLOBAL GAMBITS Michael J. Green Meet the Neighbors: Regional Responses to China’s Rise . -

Will the Post-COVID-19 World See a Retreat from Globalization?

99 Rising regionalization: will the post-COVID-19 world see a retreat from globalization? Peter Enderwick and Peter Buckley* Concerns regarding the operation of the global economy mean that recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is unlikely to see a return to the previous globalization wave. We suggest that there is an opportunity to address some of the weaknesses of globalization through a more regionally-based world economy offering a better balance between national and international interests, efficiency and resilience in global supply chains, and between growth, inclusiveness, and equity impacts. Keywords: COVID-19, globalization, regionalization 1. Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic represents the most fundamental disruption to economic activity in a century, introducing huge challenges for the global economy. Although that economy has survived past disruptions – 9/11, severe acute respiratory syndrome and the global financial crisis – none have been as immediate, prolonged or widespread as the pandemic. Unlike earlier events, it has simultaneously hit the leading economies, paralyzed links between countries, prompted a mix of responses and created uncertainty about its eventual eradication. Interestingly, for a global event, it has not triggered an effective global response. Rather, nations have pursued disparate responses based on their trade-off between the costs of virus containment and those of economic shutdown and isolation. The lack of global leadership may reflect the absence of a clear single global power or the ongoing tensions between the two leading contenders – the United States and China. One effect of the pandemic is a reconsideration of the current globalization wave and whether it should be revived or remodelled. -

Asean Economic Prospects Amid Emerging Turbulence: Development Challenges and Implications for Reform Khuong Vu

ASEAN ECONOMIC PROSPECTS AMID EMERGING TURBULENCE: DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR REFORM KHUONG VU JULY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This paper reviews the performance of ASEAN countries over the two decades since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, as well as the countries’ vulnerabilities to the U.S.-China trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic. It argues that these turbulences indicate that the world has reached an inflection point, requiring fundamental change in development thinking and approaches. This message is particularly relevant for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, which made impressive economic achievements before the COVID-19 outbreak. As all ASEAN countries have established aspirational goals for their development journeys over the next two to three decades, it is imperative that each country undertake decisive fundamental reforms and strategic shifts in order to be highly prepared, competitive, and resilient in the future development landscape. Furthermore, ASEAN will be much stronger if it can position itself as an integrated market and a well-coordinated community, in which each country endeavors to enhance not only its own fitness, but also the fitness of the region in the post-COVID-19 global economic evolution. INTRODUCTION To better project the future prospects of ASEAN countries, it is important to comprehend the The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) three prevailing distinctive features of the region: comprises 10 countries: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, harmonious diversity, development aspirations, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, and an embrace of global integration. In terms of Thailand, and Vietnam (Table 1). Situated between harmonious diversity, the 10 countries have different two rising economic powers, China and India, ASEAN religions, population sizes, political systems, and countries are facing enormous direct opportunities levels of economic development. -

China Plus One in ASEAN – the How and Why Dustin Daugherty, Maxfield Brown

China Plus One in ASEAN – The How and Why Dustin Daugherty, Maxfield Brown www.dezshira.com China Plus One Diversification o China +1 is an international business strategy that consists of the expansion of one company's current operations in China o There are two types of alternative locations: low-wage countries in Asia (Bangladesh, India..) and Association of Southeast Asian Countries (ASEAN) countries www.dezshira.com China Plus One Benefits o Cost control: Workers in Southeast Asia generally are less expensive to hire than Chinese employees o Risk Diversification: Spreading production across several markets hedges future investment in China by leaving producers less vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, currency fluctuations and tariff risks in any individual market o New Market Access – burgeoning middle class in ASEAN www.dezshira.com The Problem — a Maturing Economy, Rising Wages and Disappearing Tax Incentives Rising labor cost o A hike in wage structure- approximately 25% a year in major industry sectors. o Minimum wages in Chinese regions increased above 30% (2010 to 2016) o Other regions: Jiangxi: doubled the nominal wage o Beijing: an increase in the nominal minimum wage of 63% www.dezshira.com The Problem — a Maturing Economy, Rising Wages and Disappearing Tax Incentives o China’s base salaries across all job grades are between 5% and 44% higher than in Indonesia and other labor market among the emerging ASEAN economies o According to ECA International, the average real wage increase of 4.7% forecast for Chinese workers in 2017 is considerably higher than the global average forecast of 1.5% and the Asia- Pacific forecast of 2.6% www.dezshira.com The Problem — a Maturing Economy, Rising Wages and Disappearing Tax Incentives Shortage of qualified workers o Increasingly severe shortage of labor, especially in urban areas o A shortage of qualified workers has led to wage inflation (10% in 2012) o During the coming years, forecasts suggest that Chinese labor shortages could grow, in part, as a result of China’s one-child policy. -

China-ASEAN Corridor Opening Doors to Diverse Opportunities Contents

Borderless Business: China-ASEAN Corridor Opening doors to diverse opportunities Contents: Overview of the China-ASEAN Corridor: Opening New Doors for Chinese Businesses 3 Our Growth Watchlist: Three Sectors Driving the Future of the China-ASEAN Corridor 8 Acting with Impact: Five Focus Areas for Chinese Companies to Drive Resilient Growth in ASEAN 18 Overview of the China-ASEAN Corridor: Opening New Doors for Chinese Businesses Overview of the China-ASEAN Corridor ASEAN presents a major growth opportunity (ASEAN), an emerging economic powerhouse for Chinese companies looking to interna- as the fifth largest economy in the world by GDP tionalise. The region’s fast-growing consumer (~USD 3 trillion), offers significant trade and markets, rapidly maturing supplier landscape, investment opportunities given rising consump- and regional trade links offer Chinese compa- tion and improved manufacturing capabilities. nies strong growth potential in sectors such as high-value manufacturing, energy, and digital Economic linkages between China and ASEAN services. ‘Borderless Business: China-ASEAN have strengthened, accelerated by the former’s Corridor’ is a strategic point-of-view commis- meteoric rise to the world’s second largest econ- 1 sioned by Standard Chartered and prepared by omy by GDP. China is ASEAN’s largest import PwC, looking at high potential opportunities for partner with merchandise imports valued at cross-border growth and showcasing key USD324 billion in 2019, accounting for 23 per areas of focus for Chinese companies to suc- cent of all imports in the region and growing at ceed in the ASEAN region. In addition, this re- a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.5 port also includes insights collated via a survey per cent from 2014-19. -

China Plus One

February 2013 China Plus One Stuart Witchell Senior Managing Director, Global Risk and Investigations Practice FTI CONSULTING Philippa Symington Managing Director, Global Risk and Investigations Practice FTI CONSULTING February 2013 or the last 20 years, many Western companies have invested in China, drawn by its low production costs and enormous domestic consumer market. But in recent years, the cost advantage has diminished, while other business challenges Fhave emerged. As a result, many companies are looking to exploit opportunities in other growing Asian markets both to hold down costs and to reduce overdependence on China. THE PROBLem — a MATURING proved so alluring to Western compa- THE Solution — DIVE DEEPER EconoMY, RISING WAGES AND nies have diminished. For instance, AND/OR BRANCH OUT DISAPPEARING TAX INCENTIVES China no longer ranks as one of the To hold the line on the cost of doing cheapest labor markets in Asia. A Over the past few decades, global business in China, some multinational shortage of qualified workers has led to corporations have been entering China companies are opening new facilities in wage inflation; 10% in 2012 according to to open factories and launch business- China’s interior, where wages continue Standard Chartered. During the coming es in the services industries. This was to be lower than those on the coast. For years, forecasts suggest that Chinese motivated by an eagerness to access a example, consumer packaged goods labor shortages could grow, in part, booming Chinese market while taking giant Unilever has moved some of its as a result of China’s policy permitting advantage of relatively low production manufacturing facilities for products families to have no more than one costs and wages. -

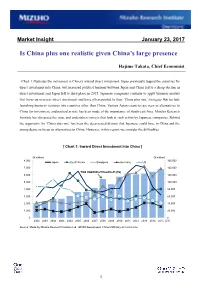

Is China Plus One Realistic Given China's Large Presence

Market Insight January 23, 2017 Is China plus one realistic given China’s large presence Hajime Takata, Chief Economist Chart 1 illustrates the movement in China’s inward direct investment. Japan previously topped the countries for direct investment into China, but increased political tensions between Japan and China led to a sharp decline in direct investment and Japan fell to third place in 2015. Japanese companies continue to apply business models that focus on overseas direct investment and have often pointed to their ‘China plus one’ strategies that include launching business ventures into countries other than China. Various Asian countries are seen as alternatives to China for investment, and particular note has been made of the importance of South-east Asia. Mizuho Research Institute has discussed the issue and undertaken surveys that look at such action by Japanese companies. Behind the arguments for ‘China plus one’ has been the deep-seated distrust that Japanese could have in China and the strong desire to focus on alternatives to China. However, in this report, we consider the difficulties [ Chart 1: Inward Direct Investment into China ] ($ million) ($ million) 8,000 160,000 Japan South Korea Singapore Germany US 7,000 140,000 Total inward direct investment (rhs) 6,000 120,000 5,000 100,000 4,000 80,000 3,000 60,000 2,000 40,000 1,000 20,000 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 (CY) Source: Made by Mizuho Research Institute Ltd. (MHRI) based upon China’s Ministry of Commerce 1 Market Insight January 23, 2017 of the ‘China plus one’ strategy regardless of preferences, and argue that it is impossible to ignore China as a market. -

China-Plus-One” Strategy

Indian Institute of Management Calcutta Working Paper Series WPS No 855 / January 2021 Global Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World: Seeking viable alternatives in a “China-Plus-One” Strategy Preetam Basu* Associate Professor, Operations Management Group Indian Institute of Management Calcutta Joka, D H Road, Kolkata 700104, INDIA e-mail: [email protected] Partha Ray Professor, Economics Group IIM Calcutta, Joka, Kolkata 700104, India e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding Author Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Joka, D.H. Road, Kolkata 700104 URL: http://facultylive.iimcal.ac.in/workingpapers 1 Global Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World: Seeking viable alternatives in a “China-Plus-One” Strategy # Preetam Basu1 and Partha Ray2 Abstract Asia played a significant role in globalization in general, and global supply chains in particular, since the mid-1970s. In this process, China has been an undisputed leader and emerged as the hub of global supply chains, supported by other countries in emerging Asia. However, since the global financial crisis of 2008, there seems to be some lull in the strength and intensity of this narrative. In more recent times, threats of the trade war and later, the COVID19 pandemic has thrown some sand in the wheels of global supply chain management. In such as situation, countries may be contemplating of diversifying its dependence on China – a strategy known as "China-Plus- One". Towards understanding this phenomenon, we propose a methodology of arriving at an aggregate ranking of the major economies of emerging Asia, built on a few standard indices such as, World Bank's Logistic Performance Index, World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Indicator, World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, and Economic Complexity Index of the Harvard University. -

China Plus 10? in the Wake of COVID–19, Manufacturers Will Face an Ever More Diffuse World

INSIGHTS | APRIL 2020 By Nicholas Blank China Plus 10? In the Wake of COVID–19, Manufacturers Will Face an Ever More Diffuse World Within the lexicon of global business, few expressions have gained as much currency in recent years as “China Plus One.” Often employed as a catch–all distillation of the tectonic shifts occurring in global manufacturing, the term fares less well as a one–size–fits–all prescription for multinational companies seeking to diversify their production bases. China’s role in this formulation is clear; less evident is which nation (or set of nations) will replace the Middle Kingdom. While economic factors—principally the rising cost of labor in China—have, for years, spurred the migration of manufacturing southward to markets including Vietnam and Thailand, as well as to markets further afield, the epochal disruption unleashed by COVID–19 has added new dimensions to the problem of how to best reconfigure supply chains to guard against risks, both anticipated and unforeseen. “China Plus One” was reportedly conceived in 2003, in the wake of the last great epidemic to befall Asia, the outbreak of SARS. Origination of the concept is credited to Japanese manufacturers, who, perhaps more so than other international investors, are all too familiar with the risks of over–reliance on Chinese manufacturing. On more than a few occasions, Japanese businesses have found themselves to be targets of government–instigated anti–Japanese riots and collateral damage in diplomatic spats between China and Japan over territorial claims. Throughout the 2010s, “China Plus One” became a common expression used by corporations of all stripes to describe their “China risk” mitigation strategy.