PART I Significance, History, People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage New Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISBN 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San irst Printing, 2002 " 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 " 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety, for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma, is allowed after prior notification to the author. New Cover Design ,nset photo shows the famous Reclining .uddha image at Kusinara. ,ts uni/ue facial e0pression evokes the bliss of peace 1santisukha2 of the final liberation as the .uddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the 3reat Stupa of Sanchi located near .hopal, an important .uddhist shrine where relics of the Chief 4isciples and the Arahants of the Third .uddhist Council were discovered. Printed in ,uala -um.ur, 0alaysia 1y 5a6u6aya ,ndah Sdn. .hd., 78, 9alan 14E, Ampang New Village, 78000 Selangor 4arul Ehsan, 5alaysia. Tel: 03-42917001, 42917002, a0: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATI2N This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to ,ndia from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in .uddhism, have made those 6ourneys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage ew Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISB: 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San First Printing, 2002 – 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 – 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety , for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma , is allowed after prior notification to the author. ew Cover Design Inset photo shows the famous Reclining Buddha image at Kusinara. Its unique facial expression evokes the bliss of peace ( santisukha ) of the final liberation as the Buddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the Great Stupa of Sanchi located near Bhopal, an important Buddhist shrine where relics of the Chief Disciples and the Arahants of the Third Buddhist Council were discovered. Printed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by: Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd., 68, Jalan 14E, Ampang New Village, 68000 Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel: 03-42916001, 42916002, Fax: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATIO This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to India from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in Buddhism, have made those journeys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

Genesis of Stupas

Genesis of Stupas Shubham Jaiswal1, Avlokita Agrawal2 and Geethanjali Raman3 1, 2 Indian Institue of Technology, Roorkee, India {[email protected]} {[email protected]} 3 Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, Ahmedabad, India {[email protected]} Abstract: Architecturally speaking, the earliest and most basic interpretation of stupa is nothing but a dust burial mound. However, the historic significance of this built form has evolved through time, as has its rudimentary structure. The massive dome-shaped “anda” form which has now become synonymous with the idea of this Buddhist shrine, is the result of years of cultural, social and geographical influences. The beauty of this typology of architecture lies in its intricate details, interesting motifs and immense symbolism, reflected and adapted in various local contexts across the world. Today, the word “stupa” is used interchangeably while referring to monuments such as pagodas, wat, etc. This paper is, therefore, an attempt to understand the ideology and the concept of a stupa, with a focus on tracing its history and transition over time. The main objective of the research is not just to understand the essence of the architectural and theological aspects of the traditional stupa but also to understand how geographical factors, advances in material, and local socio-cultural norms have given way to a much broader definition of this word, encompassing all forms, from a simplistic mound to grand, elaborate sanctums of great value to architecture and society -

Ambedkar and the Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000)

International Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 2 Issue 6 ǁ July 2017. www.ijahss.com Ambedkar and The Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000) Dr. Shaji. A Faculty Member, Department of History School of Distance Education University of Kerala, Palayam, Thiruvananthapuram Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar was one of the most remarkable men of his time, and the story of his life is the story of his exceptional talent and outstanding force of character which helped him to succeed in overcoming some of the most formidable obstacles that an unjust and oppressive society has ever placed in the way of an individual. His contribution to the cause of Dalits has undoubtedly been the most significant event in 20th century India. Ambedkar was a man whose genius extended over diverse issues of human affairs. Born to Mahar parents, he would have been one of the many untouchables of his times, condemned to a life of suffering and misery, had he not doggedly overcome the oppressive circumstances of his birth to rise to pre-eminence in India‘s public life. The centre of life of Ambedkar was his devotion to the liberation of the backward classes and he struggled to find a satisfactory ideological expression for that liberation. He won the confidence of the- untouchables and became their supreme leader. To mobilise his followers he established organisations such as the Bahishkrit Hitkarni Sabha, Independent Labour Party and later All India Scheduled Caste Federation. He led a number of temple-entry Satyagrahas, organized the untouchables, established many educational institutions and propagated his views through newspapers like the 'Mooknayak', 'Bahishkrit Bharat' and 'Janata'. -

Ánanda Thera

Ánanda Thera Ven. Ananda Ministering the sick Monk Introduction – Reading the story of Ven. Ananda Thera, we come to know the significance of paying homage to Bodhi tree. It was instructed by Buddha to plant a sapling Bodhi tree to represent him – Buddha said to Ananda – 1. “Ánanda bring a sapling from the Bodhi Tree in Buddha Gaya and plant it in Jetavana. He then said: "In my absence, let my devotees pay homage to the great Bodhi Tree that gave me protection during enlightenment. Let the Bodhi Tree be a symbol of my presence. Those who honor the Bodhi. 2. The next significant contribution was the formation of the Bhikkhuni Sangha order for the first time in Buddha’s Ministry. 3. The next, is the Ratana Sutta – Yatana Tote - whenever, some one recite Ratana Sutta – Yatana Tote – we are reminded of Ven. Ananda who first recite this paritta sutta to clean the evil off the city of Vasali. 4. He attained the Arahantship on the day of the First Council of the Dhamma, (Sangayana), post Maha Parinaibbana period. He was declared the guardian of the Dhamma because of his retentive memory. Page 1 of 42 Dhamma Dana Maung Paw, California 5. One very significant lesson we can learn from the Maha-parinibbana Sutta is Buddha’s instruction to Ananda - "Ananda, please prepare a bed for me between the twin sal-trees, with its head to the north. I am tired, and will lie down." When we meditate we should always face towards the Northerly direction to accrue the purity of the Universe. -

Download List of Famous Bridges, Statues, Stupas in India

Famous Bridges, Statues, Stupas in India Revised 16-May-2018 ` Cracku Banking Study Material (Download PDF) Famous Bridges in India Bridge River/Lake Place Howrah Bridge (Rabindra Setu) Hoogly Kolkata, West Bengal Pamban Bridge (Indira Gandhi Setu) Palk Strait Rameswaram, Tamilnadu Mahatma Gandhi Setu Ganges Patna, Bihar Nehru Setu Son Dehri on Sone, Bihar Lakshmana Jhula Ganges Rishikesh, Uttarakhand Vembanad Railway Bridge Vembanad Lake Kochi, Kerala Vivekananda Setu Hoogly Kolkata, West Bengal (Willingdon Bridge/Bally Bridge) Vidyasagar Setu Hoogly Kolkata, West Bengal *Bhupen Hazarika Setu Lohit Sadiya, Assam (Dhola Sadiya Bridge) Ellis Bridge Sabarmati Ahmedabad, Gujarat Coronation Bridge Teesta Siliguri, West Bengal Bandra–Worli Sea Link (Rajiv Gandhi Mahim Bay Mumbai, Maharashtra Setu) Golden Bridge Narmada Bharuch, Gujarat (Narmada Bridge) Jadukata Bridge Jadukata (Kynshi) West Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya Naini Bridge Yamuna Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh Jawahar Setu Son River Dehri,Bihar SBI PO Free Mock Test 2 / 7 Cracku Banking Study Material (Download PDF) Bridge River/Lake Place Bogibeel Bridge Brahmaputra River Dibrugarh, Assam Saraighat Bridge Brahmaputra River Guwahati, Assam Kolia Bhomora Setu Brahmaputra River Tezpur, Assam Narayan Setu Brahmaputra River Jogighopa, Assam New Yamuna Bridge Yamuna Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh Nivedita Setu Hoogly Kolkata, West Bengal Raja Bhoj Cable Stay Bridge Upper Lake Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh Download Important Loan Agreements in 2018 PDF Famous Statues in India Statue Person/God Place Statue -

Fhe HIUORY of HUOOHUH in Thalia

fHE HIUORY OF HUOOHUH IN THAliA S 8Q 552 867 C.3 .' '., . • , . นกั หอสมุดกลาง สำ BUD,DH1SM IN THA ILA NO ' ItJ ',WAIIG BORIBAL BURIBANDH translated by , 'Or. Luall SurlyalteDls, M.D. , ' • . " ,Pre/ace ':N 'former d8Y~. 88y50 years ago, Thai1a~d :was mostly only ".. , .ll, known from boo'ksand colourful deSCrIptions made by a :few privileged persons who had ventured to visit this country. It was ktlown as "~h~ Land of White Elephants t •• of gilded temples apd pag()das. as ci the Land of Yellow Robes" and .,' the Landof SmilesII. It was described as an island of peace and tral)quility, a haven far away from the high seas ,of up~ heaval and pOlitical unrest. ,Today, particularly since สtheม armed conflict in Korea, where, the free nationsน ofกั theห worldอ struggledุดกลา to contain the disruptive fo,rcesof ำCommun~sm. the eyes of งthe world are ส focussed upon Thailand as a possible future victim of Com munistaggressio~. , It is receiving the attention of both sides, precisely because of its privileged position. It is still an island of peace and relative prosperity, where there are class dis.. tinctiQns y~t no class hatred. Where rich and poor live peace~ fully togetl,1er because of their Buddhist tolerance 'and because ~here.is abundant food,for all. Where foreigners of every race and coUntry are met with a smile. And where the subtle tactics ~nd s'L\bversive activities of Communism have not as yet met with succesa worth speaking of, because of the peo~ ple'\i deep faith in their Religion and because of their inborn love of personal freedom, and their loyalty. -

Buddhism and Written Law: Dhammasattha Manuscripts and Texts in Premodern Burma

BUDDHISM AND WRITTEN LAW: DHAMMASATTHA MANUSCRIPTS AND TEXTS IN PREMODERN BURMA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dietrich Christian Lammerts May 2010 2010 Dietrich Christian Lammerts BUDDHISM AND WRITTEN LAW: DHAMMASATTHA MANUSCRIPTS AND TEXTS IN PREMODERN BURMA Dietrich Christian Lammerts, Ph.D. Cornell University 2010 This dissertation examines the regional and local histories of dhammasattha, the preeminent Pali, bilingual, and vernacular genre of Buddhist legal literature transmitted in premodern Burma and Southeast Asia. It provides the first critical analysis of the dating, content, form, and function of surviving dhammasattha texts based on a careful study of hitherto unexamined Burmese and Pali manuscripts. It underscores the importance for Buddhist and Southeast Asian Studies of paying careful attention to complex manuscript traditions, multilingual post- and para- canonical literatures, commentarial strategies, and the regional South-Southeast Asian literary, historical, and religious context of the development of local legal and textual practices. Part One traces the genesis of dhammasattha during the first and early second millennia C.E. through inscriptions and literary texts from India, Cambodia, Campå, Java, Lakå, and Burma and investigates its historical and legal-theoretical relationships with the Sanskrit Bråhmaˆical dharmaßåstra tradition and Pali Buddhist literature. It argues that during this period aspects of this genre of written law, akin to other disciplines such as alchemy or medicine, functioned in both Buddhist and Bråhmaˆical contexts, and that this ecumenical legal culture persisted in certain areas such as Burma and Java well into the early modern period. -

Dzogchen Forum in Moscow

No. 109 March, April 2011 Upcoming Retreats with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Photo: G. Horner 2011 Ukraine May 14–20 Crimea retreat May 21–25 Photo: D. Ibragimov SMS Base Level exam May 26–June 6 SMS First Level Training Romania June 10–16 Merigar East Retreat Evolution Is Now Italy Dzogchen Forum in Moscow June 24–30 “The Union of Manamudra and Andrei Besedin Dzogchen” by the great Master Araga July 15–18 Thirtieth Anniversary of Merigar West n 26th–30th of April something tional Affairs, which is one of the leading in the mandala zone master-classes were unique happened in Moscow: the Moscow Universities. Rinpoche explained held. And almost half of the pavilion was August 5–12 Ofi rst Dzogchen Forum “Open tra- the meaning of Evolution, and the way in fi lled with stands of the partners, like in a Initiation and Instructions of Garuda dition – to the Open World” was held. A which all of us can enter this condition. business exposition. The central and the from Rigdzin Changchub Dorje’s Terma Forum is a format that is quite different During the next days, Rinpoche’s semi- biggest was the stand of the Dzogchen August 19–23 from a regular retreat, as it implies the nar on “Essence, Nature and Energy” was community, with bigger zones for Chögyal A special Teaching: “Dzogchen Yangti” possibility to meet and share knowledge the main event of each day. On the 29th he Namkhai Norbu and Khyentse Yeshe, and in an appropriate place, and a good chance particularly presented “Dra thal drel” – his smaller zones for North and South Kun- UK of inner development. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

Witchcraft, Religious Transformation, and Hindu Nationalism in Rural Central India

University of London The London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Anthropology Witchcraft, Religious Transformation, and Hindu Nationalism in Rural Central India Amit A. Desai Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 UMI Number: U615660 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615660 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis is an anthropological exploration of the connections between witchcraft, religious transformation, and Hindu nationalism in a village in an Adivasi (or ‘tribal’) area of eastern Maharashtra, India. It argues that the appeal of Hindu nationalism in India today cannot be understood without reference to processes of religious and social transformation that are also taking place at the local level. The thesis demonstrates how changing village composition in terms of caste, together with an increased State presence and particular view of modernity, have led to difficulties in satisfactorily curing attacks of witchcraft and magic. Consequently, many people in the village and wider area have begun to look for lasting solutions to these problems in new ways. -

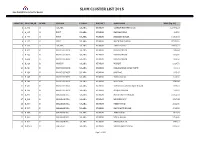

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq.