Download (1950Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2019 Working the News: Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media Jenny Hauser Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hauser, J. (2019) Working the News: Preserving Professional Identity Through Networked Journalism at Elite News Media, Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin. DOI: 10.21427/12h3-z337 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Working the news: Preserving professional identity through networked journalism at elite news media Jenny Hauser Supervisors: Dr. Harry Browne, Dr. Charlie Cullen, Prof. Michael Foley School of Media, TU Dublin Abstract The concept of journalism as a profession has arguably been fraught and contested throughout its existence. Ideologically, it is founded on a claim to norms and a code of ethics, but in the past, news media also held material control over mass communication through broadcast and print which were largely inaccessible to most citizens. The Internet and social media has created a news environment where professional journalists and their work exist side-by-side with non-journalists. In this space, acts of journalism also can be and are carried out by non-journalists. -

Brave New World Service a Unique Opportunity for the Bbc to Bring the World to the UK

BRAVE NEW WORLD SERVIce A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR THE BBC TO BRING THE WORLD TO THE UK JOHN MCCaRTHY WITH CHARLOTTE JENNER CONTENTS Introduction 2 Value 4 Integration: A Brave New World Service? 8 Conclusion 16 Recommendations 16 INTERVIEWEES Steven Barnett, Professor of Communications, Ishbel Matheson, Director of Media, Save the Children and University of Westminster former East Africa Correspondent, BBC World Service John Baron MP, Member of Foreign Affairs Select Committee Rod McKenzie, Editor, BBC Radio 1 Newsbeat and Charlie Beckett, Director, POLIS BBC 1Xtra News Tom Burke, Director of Global Youth Work, Y Care International Richard Ottaway MP, Chair, Foreign Affairs Select Committee Alistair Burnett, Editor, BBC World Tonight Rita Payne, Chair, Commonwealth Journalists Mary Dejevsky, Columnist and leader writer, The Independent Association and former Asia Editor, BBC World and former newsroom subeditor, BBC World Service Marcia Poole, Director of Communications, International Jim Egan, Head of Strategy and Distribution, BBC Global News Labour Organisation (ILO) and former Head of the Phil Harding, Journalist and media consultant and former World Service training department Director of English Networks and News, BBC World Service Stewart Purvis, Professor of Journalism and former Lindsey Hilsum, International Editor, Channel 4 News Chief Executive, ITN Isabel Hilton, Editor of China Dialogue, journalist and broadcaster Tony Quinn, Head of Planning, JWT Mary Hockaday, Head of BBC Newsroom Nick Roseveare, Chief Executive, BOND Peter -

Contact Information for Non-USC Activities

6/16/17 CURRICULUM VITAE JOEL W. HAY, PhD PERSONAL INFORMATION Business/Mail Address Professor of Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy & Professor of Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University Park Campus, Verna & Peter Dauterive Hall (VPD 214-L) 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA Business Telephone Office: (818) 338-5433 Assistant: (213) 821-7940 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Joel Hay) E-Mail [email protected] USC Websites : http://healthpolicy.usc.edu/ListItem.aspx?ID=4 http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/faculty/profile/?id=374 Graduate Program Website : http://pharmacyschool.usc.edu/programs/pep/ Schaeffer Center Street Address 635 Downey Way Los Angeles, CA 90089-3333 USA (Deliveries, e.g. Fedex, UPS) Main Phone/Front Desk: (213) 821-7940 J Hay Office: (213) 821-8160 Fax: (213) 740-3460 (ATTN: Samantha) http://healthpolicy.usc.edu Contact Information for Non-USC Activities Joel W. Hay, PhD 22101 Dardenne St. Calabasas, CA 91302 818-338-5433 [email protected] Joel W. Hay, Ph.D. -- C.V. -2- 6/16/17 EDUCATION 1974 B.A. (Summa cum laude), Economics, Amherst College 1975 M.A., Economics, Yale University 1976 M.Phil., Economics, Yale University 1980 Ph.D., Economics, Yale University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE March 2009 – Present Full Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy Professor (by courtesy), Department of Economics; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. September 2009-Present Full Professor, Health Economics and Policy Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 1992 – 2009 Associate Professor (with tenure), Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy; School of Pharmacy. -

Women2women International Leadership Program

Women2Women International Leadership Program WATCH: W2W Highlight Video The Women2Women International Leadership Program (W2W) is a program of Empower Peace, a Boston, MA based non-profit whose mission is to provide Izzah, Pakistan - young people around the world with the tools needed to advance mutual respect, understanding and cultural awareness. “ It will certainly make you There is an increasing awareness of the critical role that women and girls play believe that women hold in advancing both peace and development. Research shows that families, up half the sky and you communities, and nations prosper when girls have the opportunity to participate are one of them.” fully in every aspect of society. W2W builds a network of promising young women from around the globe, engages them in the issues that define their lives, and provides them with the tools, relationships and opportunities required to lead. W2W America W2W America is where the leadership journey begins. W2W America is a 10-day summer program that takes place in Boston, MA and is specifically designed for young women between the ages of 15 to 19 years of age. For the past eight years, W2W has provided over 600 emerging international young women leaders from 43 countries with leadership training and social entrepreneurship skills, while strengthening their cultural competencies. In many communities from which W2W delegates are selected, youth are not naturally exposed to other cultures. This lack of diversity often breeds misconceptions about other peoples and societies, both domestically and internationally. Through the training, networking and heightened comprehension of global affairs learned during this program, delegates break down barriers of misunderstanding and replace them with bridges of mutual trust and respect among often-unlikely allies. -

The Middle East and Countries of The

THE MIDDLE EAST and countries of the FSU A GUIDE to LISTENING IN ENGLISH GMT +2 TO GMT +4⁄ NOVEMBER 2010 – marcH 2011 including Egypt, Eastern Mediterranean (GMT +2), Sudan, Gulf States, Iraq (GMT +3), Iran (GMT +3∕), UAE (GMT +4) and South Afghanistan (GMT +4∕) Where you see this sign v you will hear a short News Update at 30 minutes past the hour GMT SaturdaY SundaY MondaY TuesdaY WednesdaY ThursdaY FridaY GMT 0:00 News News World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v World Briefing v 0:00 0:06 Global Business v Heart & Soul (P) 0:06 0:32 The Interview One Planet (P) 0:32 0:41 Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup Sports Roundup 0:41 0:50 Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 0:50 1:00 News World Briefing News News News News News 1:00 1:06 Friday Documentary v The Forum v Monday Documentary v Global Business v Wednesday Documentary v Assignment v 1:06 1:20 Sports Roundup v 1:20 1:32 Science in Action FOOC Health Check Digital Planet Discovery One Planet 1:32 2:00 News News World Briefing News News News News 2:00 2:06 Outlook v Assignment v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v Outlook v 2:06 2:20 World Business News v 2:20 2:32 The Strand World of Music Letter From..... The Strand The Strand The Strand The Strand 2:32 2:41 Over to You 2:41 3:00 The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v The World Today v 3:00 3:32 Politics UK Something Understood Digital Planet Americana HARDtalk/Bottom Line Heart & Soul Crossing Continents/FOOC 3:32 -

History GCSE Twitter Resource Pack Below Is a Collection of Curriculum

History GCSE Twitter Resource Pack Below is a collection of curriculum specific broadcast material, sorted by exam board and then study theme. The document will be updated as new content is added and old content is removed. OCR – History B Thematic Study - The Peoples Health c1250 to present; Crime and Punishment c1250 to present; Migrants to Britain c.1250 to present. The Peoples Health c1250 to present - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p035cygx - History of Pharmacology – charting the use of potions, herbs and drugs to relieve suffering through the ages. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p035cygy - A History of Healing – A report on healers around the world - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08q317p - In Our Time – Louis Pasteur – history of germ theory. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0644gn8 - History of the National Health Service told through one hospital, the QEII. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b007753d - In Our Time – Microbiology – discusses Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0077501 - The Making of Modern Medicine – Culturing the Germ Theory. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00k9b7r/episodes/player - Whole section. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p035cy0r - Modern Medicine - a look at how doctors in the East and West have been swapping ideas for centuries. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00775zv - In Our Time – History of anaesthetics – laughing gas in the 1790s to the discovery of ‘blessed chloroform’. - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07dnnkm - In Our Time – Discovery of Penicillin - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00wgby7 - The Birth of the welfare state - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00w65my - Clip - Health and Housing in the 19th Century Crime and Punishment c1250 to present - https://www.bbc.co.uk/education/topics/z6xmn39/resources/1 - BBC Bitesize - Crime and Punishment through time Class Clips - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b02x9rfj/clips - BBC - London’s oldest prison – the first prison for female convicts. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Tasiu Abubakar, A. (2017). Audience Participation and BBC’s Digital Quest in Nigeria. In: Willems, W. and Mano, W. (Eds.), Everyday Media Culture in Africa: Audiences and Users. Routledge Advances in Internationalizing Media Studies. Routledge. ISBN 9781138202849 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16361/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Audience Participation and BBC’s Digital Quest in Nigeria Abdullahi Tasiu Abubakar New technologies are driving changes in the media landscape on a scale and speed never envisaged before. They have impacted on the patterns and trajectories of media production and consumption, altered the spatio-temporal configuration of media-audience relationship, and widened the scope of cross cultural interactions across the globe. But they have also helped intensify the commodification of audiences, allowed manipulation of communicative exchanges, and enhanced communicative capitalism (Dean 2010). -

School Report Quiz: What Is News and Where to Find It

School Report Quiz: What is news and where to find it Test your knowledge about what news is and the places you can find it. Correct answers are shown in italics Journalist's role Q) Which of these best describes the job of journalist? 1) Someone who finds and reports newsworthy stories. 2) Someone who watches the news. 3) Someone who promotes politicians and businesses. A journalist is someone who finds newsworthy stories, creates reports and shares them with the public. Journalists do lots of different things to bring you the news, from taking pictures to doing interviews. But their core job is finding interesting, important and surprising stories that the public should hear about. What is news? Q) Which of these headlines is NOT news? 1) US President to visit UK. 2) Pupil drops pen during lesson. 3) Usain Bolt breaks 100m record. Pupil drops pen during lesson is unlikely to be a news story. Different news programmes will often cover different stories but giving your audience something they need or want to know is the starting point for choosing the right stories. Would people be interested in a pupil who dropped a pen in class? Sources Q) Contacts are... 1) People journalists talk to when they are researching stories. 2) Notebooks which contain a journalist's research. 3) The big TV screens in the newsroom. Contacts are people journalists speak to when they are researching stories. Your family, friends, neighbours and teachers can all be great sources for stories. Sources Q) What are "wires"? 1)A nickname for camera operators. -

BBC World Service and the Political Economy of Cultural Value in Historical Context

BBC World Service and the political economy of cultural value in historical context Alban Webb Andrew Smith Jess Macfarlane Nat Martin June 2014 1 Contents I Overview………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 II BBC World Service under Review……………………………………………………… 4 III Valuing BBC World Service: cultural value by any other name………….. 6 IV Reflections: national interests and strategic challenges……………………. 8 2 I Overview The cultural value of BBC World Service has been the sine qua non of British overseas broadcasting since it began in 1932. It underscored the early success of transmissions in English for all those ‘who think of the United Kingdom as home, wherever they may be’.1 The introduction, in 1938, of foreign language broadcasting and the concurrent swelling of the Corporation’s studios and offices with cosmopolitan and multilingual staff during the Second World War gave the BBC a truly international appeal. But it was the fusion of editorial practices with the capacities and sensibilities of its transnational workforce that allowed the World Service to enhance its credibility with audiences. The Cold War further emphasized the cultural value inherent in overseas broadcasting, particularly to Iron Curtain countries cut off from the rest of the world. The ability of BBC broadcasters to speak, within cultural and linguistic idioms, to the indigenous aspirations of populations under the yoke of Soviet domination influenced audience behaviour and loyalty for generations to come. More recently, the strategic context in which the World Service operates has been marked by an intensification of competition, allied to a diversification of information platforms, and methods and behaviours of engagement with audiences that still need to be properly comprehended. -

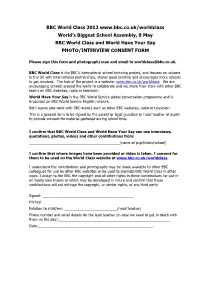

BBC World Class 2012 World’S Biggest School Assembly, 8 May BBC World Class and World Have Your Say PHOTO/INTERVIEW CONSENT FORM

BBC World Class 2012 www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass World’s Biggest School Assembly, 8 May BBC World Class and World Have Your Say PHOTO/INTERVIEW CONSENT FORM Please sign this form and photograph/scan and email to [email protected]. BBC World Class is the BBC’s international school twinning project, and focuses on schools in the UK with international partnerships, shares good practice and encourages more schools to get involved. The hub of the project is a website: www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass. We are encouraging schools around the world to collaborate and we share their story with other BBC teams on BBC websites, radio or television. World Have Your Say is the BBC World Service global conversation programme and is broadcast on BBC World Service English network. Both teams also work with BBC outlets such as other BBC websites, radio or television. This is a general form to be signed by the parent or legal guardian or head teacher of pupils to provide consent for material gathered during school time. I confirm that BBC World Class and World Have Your Say can use interviews, quotations, photos, videos and other contributions from: _____________________________________________(name of pupil/class/school) I confirm that where images have been provided or video is taken, I consent for them to be used on the World Class website at www.bbc.co.uk/worldclass. I understand the contributions and photographs may be made available to other BBC colleagues for use on other BBC websites or be used to promote BBC World Class in other ways. -

4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 Already Set up and Ready for Business

World Service Listings for 28 November – 4 December 2020 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER 2020 already set up and ready for business. BBC Thai's Chaiyot SAT 06:06 Weekend (w172x7d5fr78h9f) Yongcharoenchai set out to crack the mystery of the self-styled Iranian nuclear scientist killed SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p5kcw9djy) "CIA" food hawkers. The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Iran has urged the United Nations to condemn the assassination ‘They messed with the wrong generation’ of its top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, and it's Peru has been in the headlines for having three presidents in a pointed the finger at Israel. We explore how the incoming SAT 00:06 The Real Story (w3cszcnx) week. It’s a story of corruption allegations, impeachment and Biden administration's relationship with its traditional ally will Covid vaccines: An opportunity for science? mass protests, with young people saying their generation has shape regional tensions. had enough of the broken system which their parents put up The rapid development of coronavirus vaccines has heightened with. Ana Maria Roura has been making sense of events for Also on the programme: The number of confirmed coronavirus the hope for a world free of Covid-19. Governments have BBC Mundo. cases in the United States has passed thirteen million, with the ordered millions of doses, health care systems are prioritising pandemic still surging from coast to coast; And a new recipients, and businesses are drawing up post-pandemic plans. Lahore's toxic smog documentary explores Frank Zappa the man, his music, and But despite these positive signs, many people still feel a sense It's the time of year when many Pakistani rice farmers set fire politics. -

Doctora Honoris Causa Lisa Randall

Doctora honoris causa Lisa Randall Doctora honoris causa LISA RANDALL Discurs llegit a la cerimònia d’investidura celebrada a la sala d’actes de l’edifici Rectorat el dia 25 de març de l’any 2019 Índex Presentació de Lisa Randall per Àlex Pomarol Clotet 5 Discurs de Lisa Randall 13 Discurs de Margarita Arboix, rectora de la UAB 21 Curriculum vitae de Lisa Randall 27 Acord de Consell de Govern 131 PRESENTACIÓ DE LISA RANDALL PER ÀLEX POMAROL CLOTET És un plaer ser el padrí de la professora Lisa Randall, una persona que ha destacat per les seves contribucions en el camp de la física de partícules Les teories proposades per la professora Lisa Randall han mirat de resoldre alguns dels problemes més importants dins de la física de partícules i han inspirat una àmplia gamma de cerques ex- perimentals, especialment en el gran col·lisionador de partícules LHC del CERN a Ginebra, però també dins de l’àmbit astrofísic, motivades per les seves propostes per l’origen de la matèria fosca de l’univers Tot i això, l’interès de la professora Lisa Randall s’ha estès més enllà de la recerca d’avantguarda i també s’ha centrat a transmetre aquests coneixements al públic general Això ho ha fet possible no sols grà- cies als seus llibres de divulgació sinó també mantenint una estreta col·laboració amb artistes per obrir nous camins per portar al públic les idees científiques. En aquest aspecte, la professora Lisa Randall ha sabut relacionar els coneixements del seu camp amb els de la filosofia, les humanitats i la música, com veurem a continuació Professor