Bird Habitat and Populations in Oak Ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

Self-Guiding Geology Tour of Stanley Park

Page 1 of 30 Self-guiding geology tour of Stanley Park Points of geological interest along the sea-wall between Ferguson Point & Prospect Point, Stanley Park, a distance of approximately 2km. (Terms in bold are defined in the glossary) David L. Cook P.Eng; FGAC. Introduction:- Geomorphologically Stanley Park is a type of hill called a cuesta (Figure 1), one of many in the Fraser Valley which would have formed islands when the sea level was higher e.g. 7000 years ago. The surfaces of the cuestas in the Fraser valley slope up to the north 10° to 15° but approximately 40 Mya (which is the convention for “million years ago” not to be confused with Ma which is the convention for “million years”) were part of a flat, eroded peneplain now raised on its north side because of uplift of the Coast Range due to plate tectonics (Eisbacher 1977) (Figure 2). Cuestas form because they have some feature which resists erosion such as a bastion of resistant rock (e.g. volcanic rock in the case of Stanley Park, Sentinel Hill, Little Mountain at Queen Elizabeth Park, Silverdale Hill and Grant Hill or a bed of conglomerate such as Burnaby Mountain). Figure 1: Stanley Park showing its cuesta form with Burnaby Mountain, also a cuesta, in the background. Page 2 of 30 Figure 2: About 40 million years ago the Coast Mountains began to rise from a flat plain (peneplain). The peneplain is now elevated, although somewhat eroded, to about 900 metres above sea level. The average annual rate of uplift over the 40 million years has therefore been approximately 0.02 mm. -

The Cordilleran Ice Sheet 3 4 Derek B

1 2 The cordilleran ice sheet 3 4 Derek B. Booth1, Kathy Goetz Troost1, John J. Clague2 and Richard B. Waitt3 5 6 1 Departments of Civil & Environmental Engineering and Earth & Space Sciences, University of Washington, 7 Box 352700, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (206)543-7923 Fax (206)685-3836. 8 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada 9 3 U.S. Geological Survey, Cascade Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, WA, USA 10 11 12 Introduction techniques yield crude but consistent chronologies of local 13 and regional sequences of alternating glacial and nonglacial 14 The Cordilleran ice sheet, the smaller of two great continental deposits. These dates secure correlations of many widely 15 ice sheets that covered North America during Quaternary scattered exposures of lithologically similar deposits and 16 glacial periods, extended from the mountains of coastal south show clear differences among others. 17 and southeast Alaska, along the Coast Mountains of British Besides improvements in geochronology and paleoenvi- 18 Columbia, and into northern Washington and northwestern ronmental reconstruction (i.e. glacial geology), glaciology 19 Montana (Fig. 1). To the west its extent would have been provides quantitative tools for reconstructing and analyzing 20 limited by declining topography and the Pacific Ocean; to the any ice sheet with geologic data to constrain its physical form 21 east, it likely coalesced at times with the western margin of and history. Parts of the Cordilleran ice sheet, especially 22 the Laurentide ice sheet to form a continuous ice sheet over its southwestern margin during the last glaciation, are well 23 4,000 km wide. -

Life History Account for Lazuli Bunting

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group LAZULI BUNTING Passerina amoena Family: CARDINALIDAE Order: PASSERIFORMES Class: AVES B477 Written by: S. Granholm Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY A common summer visitor from April into September throughout most of California, except in higher mountains and southern deserts. Breeds in open chaparral habitats and brushy understories of open wooded habitats, especially valley foothill riparian. Also frequents thickets of willows, tangles of vines, patches of tall forbs. Often breeds on hillsides near streams or springs. In arid areas, mostly breeds in riparian habitats. May breed in tall forbs in mountain meadows (Gaines 1977b). An uncommon breeder in Central Valley, and rare and local above lower montane habitats. Small numbers move upslope after nesting, occasionally as high as 3050 m (10,000 ft). More widespread in lowlands in migration, occurring commonly in Central Valley (especially in fall) and desert oases (Grinnell and Miller 1944, McCaskie et al. 1979, 1988, Verner and Boss 1980, Garrett and Dunn 1981). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds mostly on insects and small seeds. Both are important foods through spring and summer (Martin et al. 1961, Bent 1968). Mostly forages in or beneath tall, dense herbaceous vegetation, shrubs, low tree foliage, and vine tangles. Takes insects and seeds from plants or from ground. Sometimes hawks insects in air and gleans foliage well up into tree canopy. Cover: Trees and shrubs and herbage provide cover. Male often sings from high perch in a tree, if present; otherwise uses a taller shrub (Grinnell and Miller 1944). -

Post-Glacial Sea-Level Change Along the Pacific Coast of North America Dan H

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons SIAS Faculty Publications School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences 8-1-2014 Post-glacial sea-level change along the Pacific coast of North America Dan H. Shugar University of Washington Tacoma, [email protected] Ian J. Walker Olav B. Lian Jordan BR Eamer Christina Neudorf See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_pub Recommended Citation Shugar, Dan H.; Walker, Ian J.; Lian, Olav B.; Eamer, Jordan BR; Neudorf, Christina; McLaren, Duncan; and Fedje, Daryl, "Post-glacial sea-level change along the Pacific oc ast of North America" (2014). SIAS Faculty Publications. 339. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_pub/339 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in SIAS Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. Authors Dan H. Shugar, Ian J. Walker, Olav B. Lian, Jordan BR Eamer, Christina Neudorf, Duncan McLaren, and Daryl Fedje This article is available at UW Tacoma Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_pub/339 1 Post-glacial sea-level change along the Pacific coast of North 2 America 3 Dan H. Shugar1,*, Ian J. Walker1, Olav B. Lian2, Jordan B.R. Eamer1, Christina 4 Neudorf2,4, Duncan McLaren3,4, Daryl Fedje3,4 5 6 1Coastal Erosion & Dune Dynamics Laboratory, Department of Geography, 7 University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, -

Advance and Retreat of Cordilleran Ice Sheets in Washington, U.S.A

Document généré le 4 oct. 2021 19:12 Géographie physique et Quaternaire Advance and Retreat of Cordilleran Ice Sheets in Washington, U.S.A. Avancée et recul des inlandsis de la Cordillère dans l’État de Washington (É.-U.) Vorstoß und Rückzug der Kordilleren-Eisdecke in Washington State. U.S.A. Don J. Easterbrook Volume 46, numéro 1, 1992 Résumé de l'article Dans la Cordillère, les glaciations se sont produites selon des modes URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032888ar caractéristiques d'avancée et de recul : 1) dépôts fluvioglaciaires d'avancée; 2) DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/032888ar poli glaciaire; 3) till; 4) dépôts fluvio-glaciaires de retrait au sud de Seattle, dans le sud des basses-terres de Puget, dépôts glacio-marins dans les basses-terres Aller au sommaire du numéro du nord, et eskers, terrasses fluvioglaciaires et petites moraines sur le plateau de Columbia. La datation au radiocarbone indique que les lobes de Puget et de Juan de Fuca ont avancé et reculé synchroniquement. Parmi les preuves qui Éditeur(s) nous contraignent à rejeter l'hypothèse selon laquelle un front en fusion, qui vêlait, serait à l'origine des dépôts glacio-marins, citons : 1) les nombreuses Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal datations au radiocarbone qui révèlent la mise en place simultanée de dépôts glacio-marins sur tout le territoire; 2) les dépôts issus de la fusion de la glace ISSN stagnante, intimement associés aux dépôts glacio-marins; 3) les preuves irréfutables d'une origine autre que marine des sables de Deming qui révèlent 0705-7199 (imprimé) que la Cordillère était libre de glace immédiatement avant la mise en place des 1492-143X (numérique) dépôts glacio-marins. -

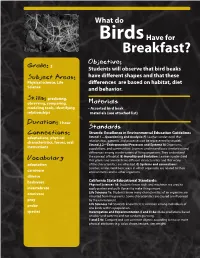

What Do Birds Have for Breakfast?

Objective: Grade: 2 Students will observe that bird beaks have different shapes and that these Subject Areas: Physical science, Life differences are based on habitat, diet Science and behavior. Skills: predicting, observing, comparing, Materials modeling tools, identifying • Assorted bird beak relationships materials (see attached list) Duration: 1 hour Standards Connections: Strands: Excellence in Environmental Education Guidelines adaptations, physical Strand 1 —Questioning and Analysis: F) Learners understand that characteristics, forces, oral relationships, patterns, and processes can be represented by models. Strand 2.2—Environmental Processes and Systems A) Organisms, instructions populations, and communities: Learners understand basic similarities and differences among a wide variety of living organisms. They understand the concept of habitat. B) Heredity and Evolution: Learners understand Vocabulary that plants and animals have different characteristics and that many adaptation of the characteristics are inherited. C) Systems and connections: Learners understand basic ways in which organisms are related to their carnivore environments and to other organisms. diverse herbivore California State Educational Standards: Physical Sciences 1d: Students know tools and machines are used to invertebrate apply pushes and pulls (forces) to make things move. omnivore Life Sciences 1c: Students know many characteristics of an organism are inherited from the parents. Some characteristics are caused or influenced prey by the environment. probe Life Sciences 1d: Students know there is variation among individuals of one kinds within a population. species Investigation and Experimentation (I and E) 4a: Make predictions based on observed patterns and not random guessing. 1 and E 4c: Compare and sort common objects according to two or more physical attributes (e.g. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Hairy) Manzanita (Arcotostaphylos Columbiana

(Hairy) Manzanita (Arcotostaphylos columbiana) RANGE Hairy manzanita is found along the coast from California north to Vancouver Island and the Sunshine Coast. Typically Manzanita is found in the open and in clearings, on shallow, strongly drained soils on rock outcrops and upper slopes. It will tolerate a variety of soil textures and parent materials. Occasionally it is found in open, young Douglas-fir forest. Manzanita does not tolerate deep shade. Photo courtesy of Moralea Milne Manzanita on rock outcrop in Metchosin District HABITAT AND LIFE HISTORY Hairy manzanita is an early colonizer of disturbed plant communities, developing after removal of the forest cover; Manzanita will continue to grow in the understory of an open forest. Black bear, coyote, deer, and various small mammals and birds eat Manzanita fruit. The leaves and stems are unpalatable to browsing wildlife such as deer. Manzanta can flower sporadically throughout several months allowing many invertebrates and hummingbirds to feed on the nectar. Brown elfin butterflies use Manzanita as a host plant, meaning they lay their eggs on Manzanita and the caterpillars use the plant as their food source. DESCRIPTION Hairy Manzanita is an erect or spreading evergreen shrub. It will grow from 1 to 3 metres in height. The bark on mature shrubs is reddish, flaking and peeling, much like arbutus bark. Young twigs and branches are grayish and hairy. Photo courtesy of Will O’Connell. The photo to the right shows the leaves of a young Manzanita on Camas Hill. Leaves are evergreen and egg or oblong shaped. Leaves are grayish and the undersides of leaves are hairy. -

Clearlake Housing Element Update 2014-19 Final

City of Clearlake Housing Element 2014-19 Chapter 8 of the Clearlake 2040 General Plan Adopted on March 26, 2015 City Council Resolution 2015-06 Prepared by: 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 8.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Housing Element Content and Organization ............................................................................... 3 Data and Methodology ................................................................................................................ 5 Public Participation ..................................................................................................................... 5 8.2 Regulatory Framework........................................................................................................... 7 Authority ...................................................................................................................................... 7 State Housing Goals ................................................................................................................... 7 Recent Legislation ...................................................................................................................... 7 General Plan Internal Consistency ............................................................................................. 8 Regional