The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Teachers' of Mani in the Acta Archelai and Simon Magus

THE ‘TEACHERS’ OF MANI IN THE ACTA ARCHELAI AND SIMON MAGUS 1 by ESZTER SPÄT Abstract: This paper aims to prove that the biography of Mani in the Acta Archelae of Hegemonius, which contains a great number of completely ctitious elements, was in fact drawn up on the le of Simon Magus, pater omnium haereticorum , using the works of heresiologists and the apocryphal acts, espe- cially the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitiones , as a model and source. There are a great number of elements in this Vita Manis that bear a strong resemblance to the well known motives of Simon’s life. Projecting Simon’s life over that of Mani serves as tool to reinforce the image of Mani that Hegemonius tried to convey: that of just another ‘run of the mill’ heretic, one in the long line of the disciples of Simon, and a fraud and devoid of any originality. The Acta Archelai of Hegemonius, 2 composed between 330 and 348 in Syria, 3 was the rst Christian work written against Manichaeans. The text of the Acta, as a whole, has survived only in the Latin translation, though a great part of its Greek text has been preserved in the Panarion (or ‘Medicine Chest’) of Epiphanius, who seems to have often copied his source almost word for word in the chapter on Manichaeism. 4 Besides being the rst it was also, in many respects, the most in uential. It was a source of mate- rial, both on Manichaean mythology and on the gure of Mani, for a long list of historians and theologians who engaged in polemics against the 1 I express my thanks to Professor J. -

Information on Pre-Urban Hymns and Evaluations of Those Who Have Tried to Write “Metrical” Translations—With Good and Poor Examples

What you need to know about Roman Catholic hymnody: Information on pre-Urban hymns and evaluations of those who have tried to write “metrical” translations—with good and poor examples Criticism of the Urbanite revisions: John Mason Neale (*Rev.), Mediæval Hymns (1851), introduction: “[...] In the third [or classical period, the Roman Church …] submitted to the slavish bondage of a revived Paganism.” Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), Fernand Cabrol (Dom) OSB, “Breviary” (VI. Reforms): Urban VIII, being himself a Humanist, and no mean poet, as witness the hymns of St. Martin and of St. Elizabeth of Portugal, which are of his own composition, desired that the Breviary hymns, which, it must be admitted are sometimes trivial in style and irregular in their prosody, should be corrected according to grammatical rules and put into true meter. To this end, he called in the aid of certain Jesuits of distinguished literary attainments. The corrections made by these purists were so numerous – 952 in all – as to make a profound alteration in the character of some of the hymns. Although some of them without doubt gained in literary style, nevertheless, to the regret of many, they also lost something of their old charm of simplicity and fervor. At the present date, this revision is condemned, out of respect for ancient texts; and surprise may be expressed at the temerity that dared to meddle with the Latinity of a Prudentius, a Sedulius, a Sidonius Apollinaris, a Venantius Fortunatus, an Ambrose, a Paulinus of Aquileia, which, though perhaps lacking the purity of the Golden Age, has, nevertheless, its own peculiar charm. -

Orosius' Histories: a Digital Intertextual Investigation Into The

comprehensive and detailed manual exploration of all of Orosius’ references. Orosius’ Histories: A Digital “It would be burdensome to list all of the Vergilian Intertextual Investigation echoes [...]” (Coffin, 1936: 237) What Coffin describes as “burdensome” can be into the First Christian accomplished with machine assistance. To the best of History of Rome our knowledge, no existing study, traditional or computational, has quantified and analysed the reuse Greta Franzini habits of Orosius. [email protected] The Tesserae project, which specialises in allusion Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany detection, is the most similar to the research presented here (Coffee, 2013), with the difference that it does not yet contain the text of Orosius nor many of Marco Büchler its sources, and that the results are automatically [email protected] computed without user input. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany In contrast, our approach, TRACER (Büchler et al., 2017), offers complete control over the algorithmic process, giving the user the choice between being Introduction guided by the software and to intervene by adjusting The research described in these pages is made pos- search parameters. In this way, results are produced sible by openly available Classical texts and linguistic through a critical evaluation of the detection. resources. It aims at performing semi-automatic anal- Research Questions and Goal yses of Paulus Orosius’ (385-420 AD) most celebrated work, the Historia adversum Paganos Libri VII, against Our research began with the following questions: its sources. The Histories, as this work is known in Eng- how does Orosius adapt Classical authors? Can we lish, constitute the first history (752 BC to 417 AD) to categorise his text reuse styles and what is the optimal have been written from a Christian perspective. -

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy The lengthy letter that follows was written by His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Piraeus, Seraphim, and His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Dryinoupolis, Andrew, both of the Church of Greece. It was sent to Pope Francis on April 10, 2014. The Orthodox Christian Information Center (OrthodoxInfo.com) assisted in editing the English translation. It was posted on OrthodoxInfo.com on Great and Holy Monday, April 14, 2014. The above title was added for the English version and did not appear in the Greek text. Metropolitan Seraphim is well known and loved in Greece for his defense of Orthodoxy, his strong stance against ecumenism, and for the philanthropic work carried out in his Metropolis (http://www.imp.gr/). His Metropolis is also well known for Greece’s first and best ecclesiastical radio station: http://www.pe912fm.com/. This radio station is one of the most important tools for Orthodox outreach in Greece. Metropolitan Seraphim was born in 1956 in Athens. He studied law and theology, receiving his master’s degree and his license to practice law. In 1980 he was tonsured a monk and ordained to the holy diaconate and the priesthood by His Beatitude Seraphim of blessed memory, Archbishop of Athens and All Greece. He served as the rector of various churches and as the head ecclesiastical judge for the Archdiocese of Athens (1983) and as the Secretary of the Synodal Court of the Church of Greece (1985-2000). In December of 2000 the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarch elected him as an auxiliary bishop of the Holy Archdiocese of Australia in which he served until 2002. -

Twenty Third Sunday in Ordinary Time September 5, 2021

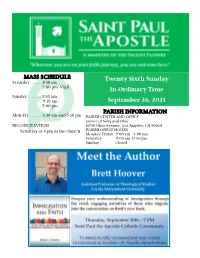

MASS SCHEDULE Twenty Sixth Sunday Saturday .......... 8:30 am 5:00 pm Vigil In Ordinary Time Sunday ............. 7:30 am 9:30 am September 26, 2021 5:00 pm PARISH INFORMATION Mon-Fri ............ 6:30 am and 5:30 pm PARISH CENTER AND OFFICE Corner of Selby and Ohio RECONCILIATION 10750 Ohio Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 Saturday at 4 pm in the church PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday-Friday 9:00 am—4:00 pm Saturday 9:00 am-12:00 pm Sunday Closed Page 2 September 26, 2021 Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – The Annual Fall Festival is here! The theme is One Love, a response to the pandemic – one love that flows from God. Our Festival Team led by Wanda Ahmadi have taken every precaution in this time of COVID. To attend in person, full vaccination is strongly recommended and/or a COVID test within 72 hours of attending; masks are to be worn at all times except when eating or drinking; practice physical distancing; and, wash hands fre- quently. See you on the Ferris wheel! Our next faith formation program is a special presentation of a new book, “Immigration and Faith: Cultural, Biblical, and Theological Narratives” by professor of theology at Loyola Marymount University, Brett Hoo- ver on Thursday, September 30 at 7 PM in the Church. Brett utilizes vivid and engaging narratives of those who migrate to see migration through the lens of our faith. The book is available for purchase at the Parish Office and will be available at the presentation. You may attend online at St. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2

St. Paul the Apostle1 by Kenneth John Paul Pomeisl2 St. Paul was born in the town of Tarsus in Cilicia which we today call Turkey around the year 3 A.D. His original name was actually Saul. He was a Pharisee which were a group of very devout Jews who were very serious about “the Law”. After Pentecost the Church, known then as “the Way”, slowly began to grow. As it did many of the Jews did not like this. They thought these newcomers were heretics. Saul was involved with putting these people in prison. He was at the execution of the first martyr, St. Stephen, who died by stoning. As he died St. Stephen asked God to forgive those who were killing him. Saul would continue to arrest every follower of the Way he could find. Some people believe that because of what St. Stephen did and how these people acted Saul started to have doubts about what he was doing but he would not change his mind. Then one day Saul was struck by a great light and blinded. As he was down here heard a voice asking “Saul, Saul, Why do you persecute me?” Saul asked this voice who he was and the reply was “I am Jesus, who you are persecuting”. After this Saul has his sight restored and becomes a Christian himself. After a while he is sent on missions to preach the Gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews). St. Paul endures many hardships but creates many Churches and during this time writes many of his letters which we know today as Epistles in the New Testament. -

In This Issue: Vocations Retreat 3 Rector’S Ruminations 4 Christian Awareness 5

17 February 2019 Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time Weekly Bulletin for the Cathedral of St. Joseph, Wheeling, West Virginia Vol. 8, No. 12 In this Issue: Vocations Retreat 3 Rector’s Ruminations 4 Christian Awareness 5 Saint Joseph Cathedral Parish is called to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ as a community. We are committed: to our urban neighborhoods, to being the Cathedral of the Diocese, and to fellowship, formation, sacrament, and prayer. Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time Jeremiah 17:5-8; Psalm 11-2, 3, 4, 6 1 Corinthians 15:12, 16-20; Luke 6:17, 20-26 Today’s readings speak of an essential quality for the Christian disciple — hope. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, ThisAt The Cathedral Week “Hope is the theological virtue by which we desire the kingdom February 17 - 24, 2019 of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ’s promises and relying not on our own strength but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1817).” In many ways, this is the very definition of a life of a Christian disciple vvvvv — focusing on eternity as we live our daily lives and relying on God to provide for our needs and satisfy our deepest longings for meaning and happiness. SUN SIXTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME The First Reading from the Prophet Jeremiah paints a vivid 17 picture of the difference between the person who puts his trust 6:00 pm (Sat) Mass for the Parishioners in fellow humans versus the person who relies on — or, in other 8:00 am Mass for Julia Bartolovich words, hopes in — the Lord. -

Female Identity and Agency in the Cult of the Martyrs in Late Antique North Africa

Female Identity and Agency in the Cult of the Martyrs in Late Antique North Africa Heather Barkman Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For admission to the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Religious Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Heather Barkman, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Outline of the Chapters 9 Identity, Agency, and Power: Women’s Roles in the Cult of the Martyrs 14 Methodology 14 i. Intermittent Identities 14 ii. Agency 23 iii. Power 28 Women’s Roles 34 Wife 35 Mother 40 Daughter 43 Virgin 49 Mourner 52 Hostess 56 Widow 59 Prophet 63 Patron 66 Martyr 71 Conclusion 75 Female Martyrs and the Rejection/Reconfiguration of Identities 78 Martyrdom in North Africa 80 Named North African Female Martyrs 87 i. Januaria, Generosa, Donata, Secunda, Vestia (Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs) 87 ii. Perpetua and Felicitas (Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas) 87 iii. Quartillosa (Martyrdom of Montanus and Lucius) 89 iv. Crispina (Passion of Crispina) 90 v. Maxima, Donatilla, and Secunda (Passion of Saints Maxima, Donatilla, and Secunda) 91 vi. Salsa (Passion of Saint Salsa) 92 vii. Victoria, Maria, and Januaria (Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs) 93 Private Identities of North African Female Martyrs 95 Wife 95 Mother 106 Daughter 119 Private/Public Identities of North African Female Martyrs 135 Virgin 135 Public Identities of North African Female Martyrs 140 Bride of Christ 141 Prophet 148 Imitator of Christ 158 Conclusion 162 Patrons, Clients, and Imitators: Female Venerators in the Cult of the Martyrs 166 iii Patron 168 Client 175 i. -

A Christian Approach to Literary Criticism: a Non- Moralistic View

A CHRISTIAN APPROACH TO LITERARY CRITICISM: A NON- MORALISTIC VIEW W. G .J. PretorÍUS M. A.-student, Department o f English. PU for CHE The common question: “Is a Christian approach to literary criticism feasible?” may be more profitably reformulated as: “How should a Christian approach to literary criticism be?”. It is clearly not a matter of the possibility of such an approach, but a challenge of formulating a new critical theory. “What could be simpler and easier than to say what a work of art is, whether it is good or bad, and why it is so?” (Olson, 1976, p. 307). The problem of value judgments in literary criticism, contrary to Olson’s view, has proved to be the most complex of all literary problems throughout the history of criticism. It is also thi central issue underlying the distinction between different approaches to literatur The formalist critic is traditionally reticent about value judgments and con centrates upon close reading of texts and implicit evaluation. Contemporary formalists, however, tend to move away from the ideal of critical objectivity On the other hand, the moralist critic is primarily concerned with the purpose of the literary work. In Naaldekoker, D. J. Opperman seriously doubts the possibility of a Calvinist approach to art, which he regards as a contradictio in terminis (pp. 61-63). I shall attempt in this essay to show that there is a valid literary criticism which is neither exclusively based on aesthetic judgment, nor an attempt to subordinate literature to religion in a moralistic way, and that such criticism originates from a C hristian vision o f life. -

Saint Peter's

Saint Peter’s NET Jesus said to Peter, “Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.” Matthew 4:19 Mission Statement: We are an inclusive, From the Rector forward-looking Episcopal parish that seeks to grow in Christ through worship, Dear Members and Friends, education and fellowship, serves Christ by ministering to local and global As I write to you on this eleventh anniversary of our joint ministry here at St. communities and shares Christ in Peter’s, it brings back memories of our early days together. I remember my following His command to “Love one installation service on January 25, 2006, a frigid cold Wednesday evening, another as I have loved you.” just a couple days after Susan and I came to Phoenixville. Everything was Vision Statement: Our vision at St. new and unfamiliar. One thing I remember vividly though was the Peter’s is to be an inclusive, vibrant excitement of the congregation in having us here and we clearly felt the love Christian community honoring our and welcome the church had for us. The white stole with names of the Episcopal heritage by achieving congregation printed on it given to me that day symbolized your love for me. excellence in worship, mission, education and fellowship. I thank God for each and every one of you who were here at that time and all those who have since joined us in this beautiful journey together in God’s Staff ministry and mission and I pray that God would continue to bless us as we Very Rev. -

SEDULIUS, the PASCHAL SONG and HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World

SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World David Konstan and Johan C. ! om, General Editors Editorial Board Brian E. Daley Erich S. Gruen Wendy Mayer Margaret M. Mitchell Teresa Morgan Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Michael J. Roberts Karin Schlapbach James C. VanderKam Number 35 SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Volume Editor Michael J. Roberts SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Carl P. E. Springer Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Copyright © 2013 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions O! ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sedulius, active 5th century. The Paschal song and hymns / Sedulius ; translated with an introduction >and notes by Carl P. E. Springer. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature. Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; volume 35) Text in Latin and English translation on facing pages; introduction and >notes in English. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-743-0 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-744-7 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-768-3 (hardcover binding : alk.